Celeste Dupuy-Spencer has been painting up a storm. The artist told art blogger Brienne Walsh she usually takes 6 months to a year and a half to finish a picture but for “Wild and Blue,” her first solo show in New York (which runs until October 7th at the Marlborough Contemporary Gallery), she only had the summer and the “paintings just got ripped out of me.” More than a few of her pictures hint at hurricane weather. And Dupuy-Spencer, who’s lived in New Orleans (though she’s based in L.A. now), knows from floods of feeling. Pictures like Cajun Navy and Lake Pontchartrain look back to Katrina’s aftermath but are all up in this time of climate change.

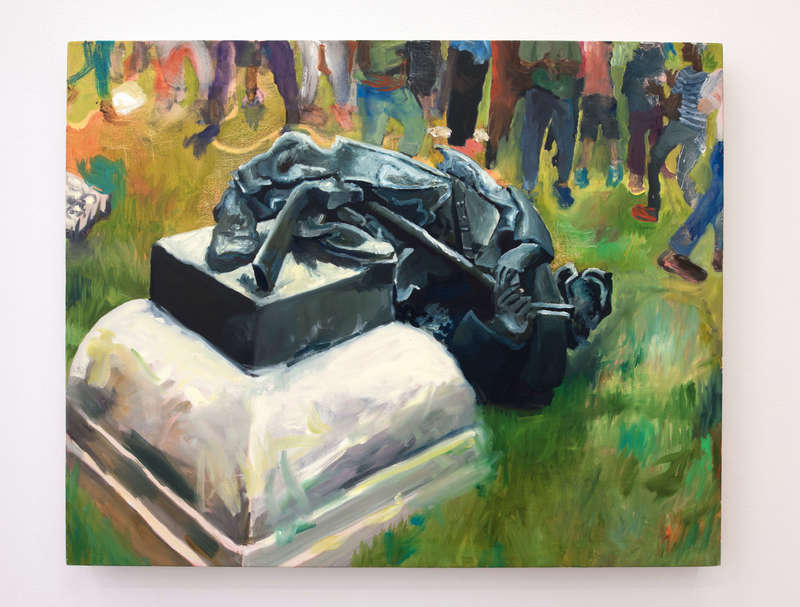

Dupuy-Spencer is “painting the news” as one reviewer has written in New Republic, citing her picture of the Confederate monument torn down last month in Durham, which “amounts to a kind of monument to the search for social justice.”

Dupuy-Spencer is “painting the news” as one reviewer has written in New Republic, citing her picture of the Confederate monument torn down last month in Durham, which “amounts to a kind of monument to the search for social justice.”

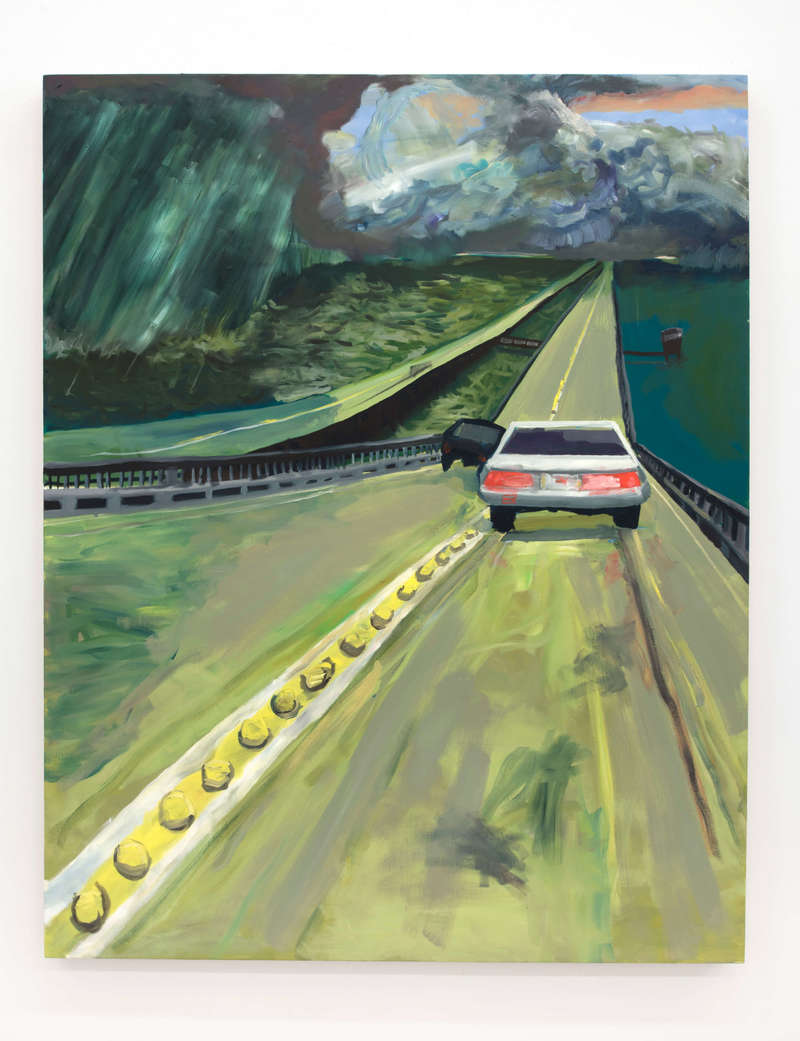

Dupuy-Spencer puts a conscious spin on her raw art instincts. She sets dance-y fauvist colors on the protestors’ side against the statue’s alabaster foundation. It’s hard for this viewer to resist adding symbolic weight to the whiteness of that base—which has been exposed in the wake of Charlottesville? I’d guess Dupuy-Spencer meant to brush on through to the core of Trump’s support. What’s certain is she’s aware cultural strife might turn into civil war. I may be projecting (again), but I take the next painting as an evocation of the divided house we live in. America’s on the edge of the cliff and waters are rising…

The painting above is untitled and Dupuy-Spencer might nix my interpretation. Put off by mansplaining, she’d probably prefer to avoid any overly didactic approach to her work. OTOH, she wants viewers of her paintings to dig forms of American dailiness that have been disdained by suburban gentry and urban haute bourgeoisie. One of her table paintings takes aim at genteel culturalism in the Age of Trump. Along with PBS/PC virtue-signaling detritus on offer, there’s a book with a subtitle: “How to Convince/Prove It’s Not Your Fault.”

The title of Dupuy-Spenccer’s exhibition reminds me of a moment when I had to confront my own Northern Man’s obliviousness to the best that had been heard and sung in my nation. The first time I heard “Wild and Blue” was when Sally Timms sung it for The Mekons in a mid-80s show at CBGBs. It remains sort of shaming to recall that twenty years after the British Invasion I still needed Brits to steer me to “Wild and Blue.” John Anderson’s original version had been a hit on Country radio years before The Mekons covered it. But I’d missed the high lonesome melody and the perfectly mysterious couplets that invite listeners to invest the lyrics with secrets of their own couplings.

It occurs to me Dupuy-Spencer, who’s an Out lesbian, may once have found queer truth in this verse:

“In somebody’s room on the far side of town

With your mind all made up and the shades all pulled down

Somebody is trying to satisfy you

But he don’t know you’re wild and blue”

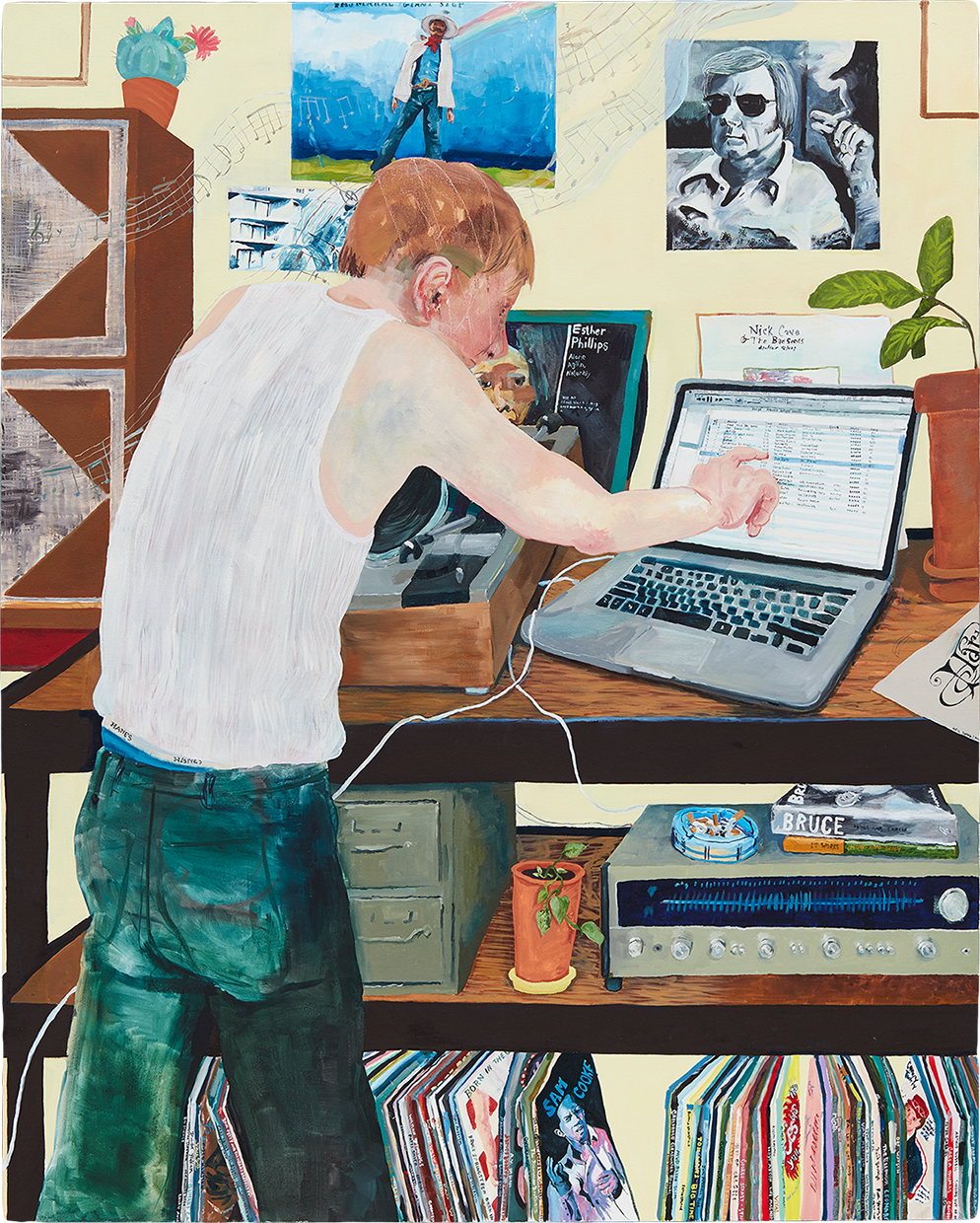

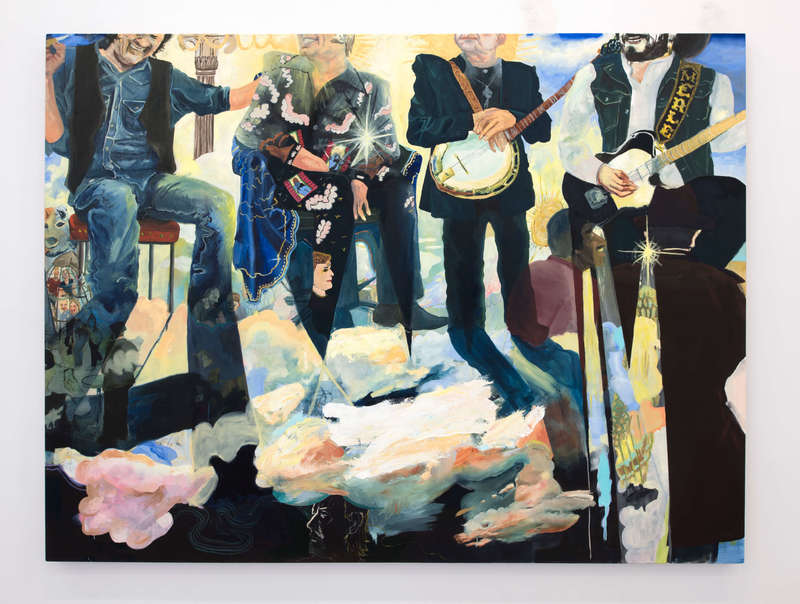

Dupuy-Spencer senses her taste for Country music distances her from NPR-smart sets. “Wild and Blue” features portraits of her Southern culture heroes, including the wonderful Country singer and guitarist Vince Gill.[1] There’s also a sketch of Gill and guitar inscribed with George Jones’ nickname for the younger player, “Sweet Pea.” Jones—perhaps the greatest Country singer ever—is something of a presiding spirit for Spencer. In her painting Fall With Me For A Million Days (My Sweet Waterfall), which was shown at this year’s Whitney Biennial, a photo of Possum (to use his nickname) looks back “as a guy scans his computer’s music library (in the throes of an attack of memories) and slouches—his love and nostalgia is so overwhelming it erupts into a painful back deformity.” Per a commentary by Dupuy-Spencer’s ex-lover Em Rooney (who also assures us the painting is a not-so-disguised self-portrait of Dupuy-Spencer).

Endless love and clarity about down home deformations seem implicit in “Wild and Blue’s” Jones’ tribute. George is setting in heaven joshing with three other dead country souls. These Southern cultural avatars have risen again, but they’re all missing the tops of their heads. That had me scratching mine, but I think I got a clue to the puzzle from Dupuy-Spencer’s painting of the downed Confederate monument. The hands of that statue had made me think of Trump’s fetish about his own digits. But Dupuy-Spencer (who’s had a beef with tendentious politicos at World Socialist Website)[2] knows from Marx (and Jefferson’s “dead hand of the past”). She’s surely alive to how tradition weighed like a grey ghost on the brains of white Southerners like George Jones. In her heaven (and George’s), she’s lopped off her heroes’ foreheads and frontal lobes, freeing their bodies and souls from the twisted part of their brains.

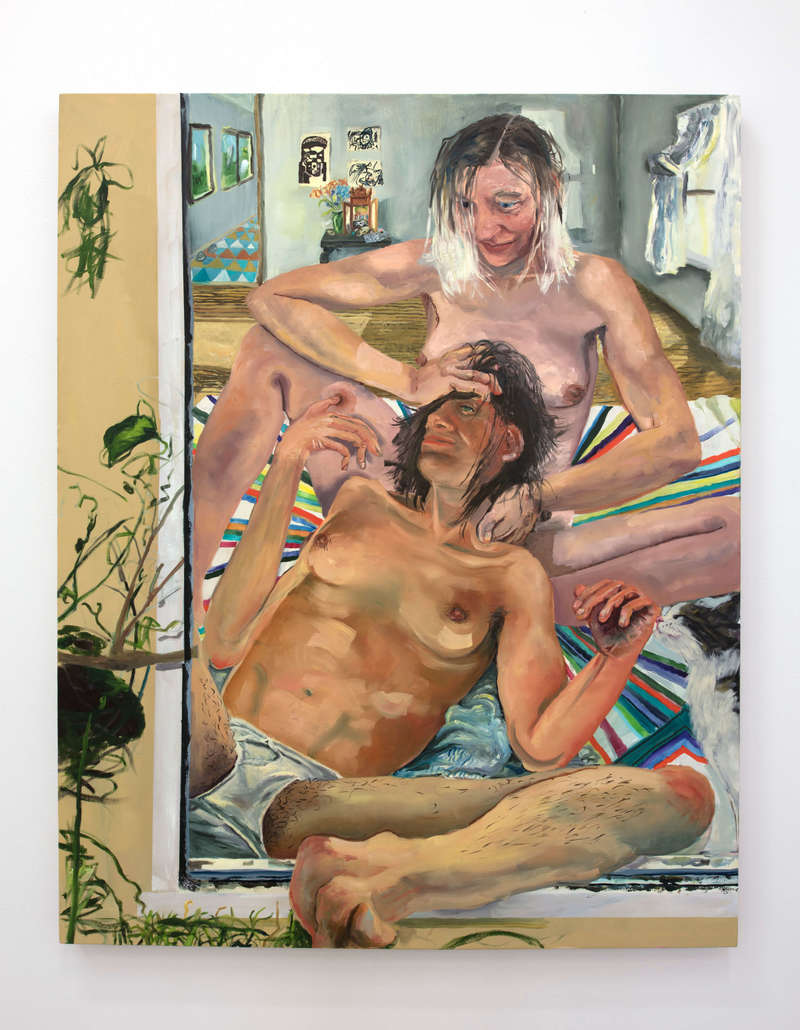

Bodies and minds are in synch in Sarah—a blissful image of Dupuy-Spencer and her girlfriend…

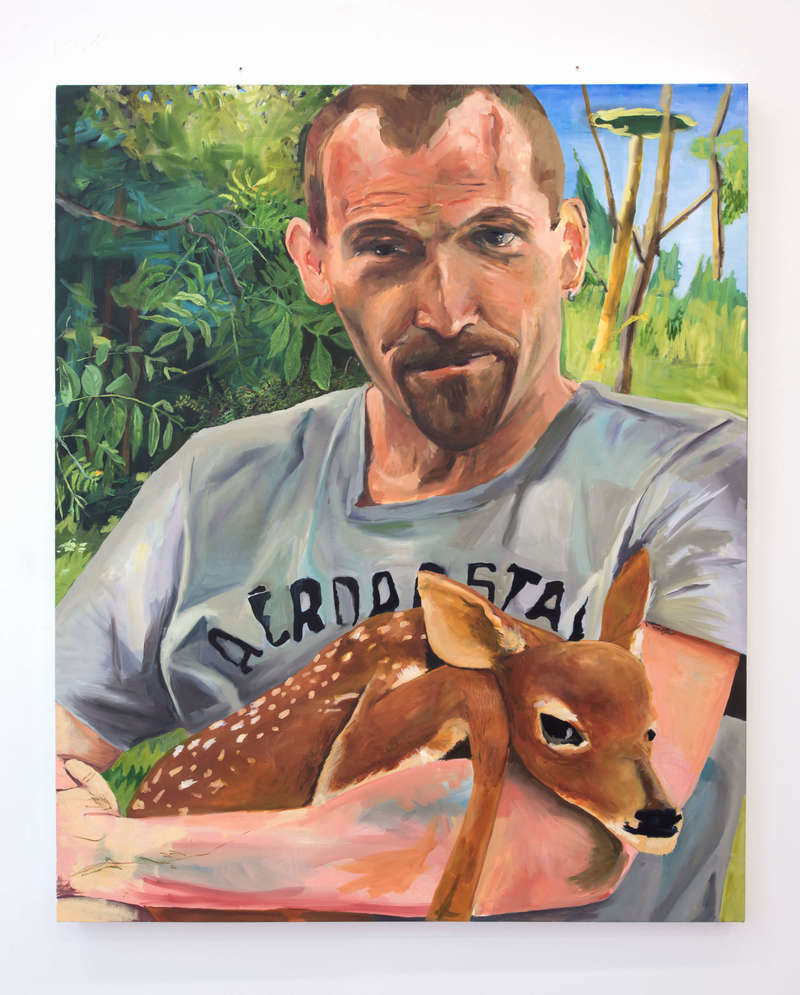

Blogger Walsh cops to envying Dupuy-Spencer’s lesbian eros but she’s struck as well by the painter’s felt tenderness for white working class men—“a queer white woman who says she doesn’t like men, makes space for white maleness to be loved.” Maybe the sweetest pea in the “Wild and Blue” show is the skinny white guy with an earring and receding hairline who’s depicted holding a baby deer in R. DiMeo III.

Walsh’s blog post gives us some back story:

This is Dupuy-Spencer’s first love; the first person she ever kissed. “I found him on Facebook through his sister,” she told me. “I didn’t know if he was alive. I was waiting to see this face… he’s suffered addiction, and he’s had a tough go of it. And all of a sudden this picture pops up, and he’s holding a baby deer looking as sweet as can be.” Her voice, as she says the last part, softens so much that in the recording, it almost sounds like she’s crying.

Walsh muses that Dupuy-Spencer’s lost boy “is the sort of person you see more often in mug shots than art”—a line that led me back to revelations in T.J. Clark’s Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution. Clark told the thrilling story of how Courbet’s populist paintings shocked critics and moved French working class people to crowd into the Salon of 1851 where, thanks to Courbet, they could see themselves on canvasses for the first time.[3] Dupuy-Spencer must hope against hope her politics of culture reaches everyday people like her ex-boyfriend and his class mates.[4]

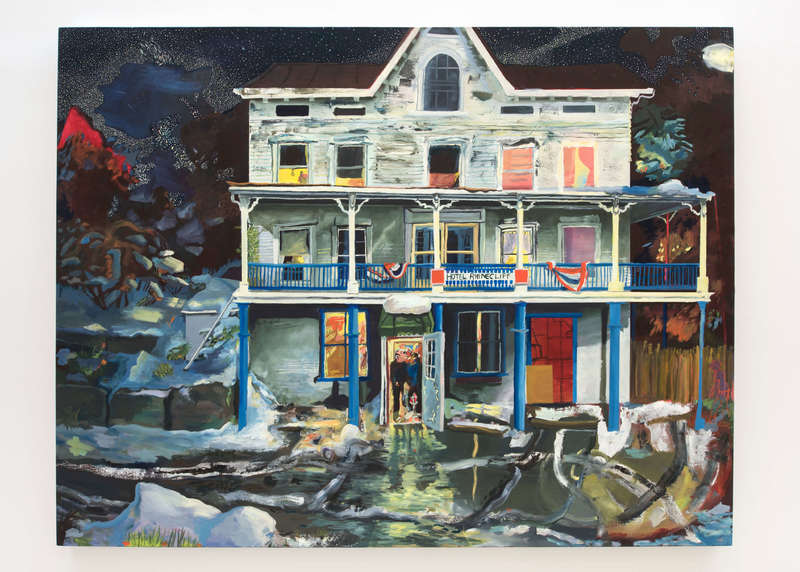

My favorite painting in “Wild and Blue” is another “image of the people,” though its Hudson Valley populism may be harder to parse than Dupuy-Spencer’s tributes to ways of being Southern. Rokeby depicts an informal party at a beautiful but homey estate owned by Ricky Aldrich–a sweet spot where Dupuy-Spencer hung out as a kid.

Walsh again provides a helpful gloss:

Dupuy-Spencer told me that the property had been “passed down through generations long after the money has been gone”…In the center [of the painting], Ricky Aldrich, sitting in a chair, looks at the viewer as if he knows we’re there. The painting shows the type of community that so many people fantasize about finding in today’s fractured world.

Aldrich’s gaze and the green expanse stretching out behind him toward the sunset place Rokeby in the tradition of proprietorial landscape paintings. But the painting’s communal feel makes it close to the antithesis of a picture like Gainsborough’s Mr. and Mrs. Anderson, which John Berger famously cited in his Marxist art history project, Ways of Seeing. Berger first presented the full painting of the Andersons in their proud land before zeroing in on their mean faces.

There are no mean faces in Rokeby. Walsh is moved by what she sees as the various dads’ responsiveness to kids in the multi-generational grouping on the porch. But I doubt elders in this picture are meant to be seen chiefly as supremely attentive “good dads.” I think Rokeby portrays a scene of social living that hints at an alternative to the new bourgeois norm of nurture by helicopter parents. Dupuy-Spencer seems aware kids don’t require adults to hover over them. What they really need as they grow older are elders who can model what it means to have a vocation. A riff in Walsh’s blog post is suggestive on this score:

Born and raised in Rhinebeck, New York, before it became, as Dupuy-Spencer puts it, “the Upper East Side,” she is nostalgic for the community of poets, writers, carpenters and artisans she grew up around. “They were really good, hard workers…”

Which brings us back to where we came in. Dupuy-Spencer’s identification with the working class seems to be founded on her own labor theory of value.

I should probably knock off now. But Dupuy-Spencer’s nostalgia takes me back to my block. It’s been gentrified too. But we still got some hard workers who are hanging on. Over the last month a multi-culti crew has been working together to keep a landlord from bringing a nuisance complaint that might lead to the eviction of an Asian widow who’s in rehab now, recovering from a stroke. This elder must have known famine in a Chinese village cos she was unable to pass up any food bargain. Every room in her place was packed to the ceiling with bags of rice, pallets of juice, cans of red, black and pink (?) beans. Before we started to clean house, roaches and mice had ruled for years. It was a heavy, smelly job and we needed music to keep us going. My older brother (and volunteer-in-chief) played a lot of classic jazz and Cuban stuff but the song that amped us up the most was George Jones’ “She Thinks I Still Care.” (See, there is a justification for this addendum.) Our Dominican homies yee-hawed along with me and my brother as we all pretended not to care.

I’ll end with another story from the state of Jones since it seems to fit under Dupuy-Spencer’s “Wild and Blue” aegis. Back around the time of the first Gulf War, me and a bunch of my buds ended up at an Upper West Side party which began to die softly when a strumming folkie tried to turn it into his hoot. He segued from p.c. protest songs to precious mush. When he sang out “look into my face” an Irish-American friend of mine turned on his heel and headed straight to the liquor cabinet for stronger drink. An hour or so later, that friend and the rest of my crew were gathered around a boom box in the kitchen singing along with a George Jones mix-tape. Our host—an African American woman born in Mississippi—judged not. That folkie goodie had rubbed her wrong too. On this one-night stand in the Apple, George Jones became our voice of protest against the reign of not-in-my-names.

Notes

1 Gill and singer Amy Grant (one of the biggest stars in Christian Contemporary music) drew heavy fire from faith-ridden fundamentalists when they married after divorcing their spouses in the 90s. It occurs to me “Let Her In”–a “divorce” song of Gill’s (and one of my faves from his catalogue)–might have had extra resonance for Dupuy-Spencer who is herself a child of divorced parents.

2 Dupuy-Spencer insists she was misquoted in an interview published at WSW, which made her out to be a dim critic of “identity politics.” While Dupuy is alive to limits of class-bound forms of multi-culturalism, she sees her work as a contribution to anti-racist struggles.

3 The frisson of Courbet’s sexier pictures—“Women with White Stockings” etc.—might have been generative as Dupuy-Spencer imaged jouissance in Sarah.

4 Which may be one reason why she invokes Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the U.S.A in Fall With Me For A Million Days.