Questlove says it all well.

American hip-hop is usually based on imitation, and it is meant to produce artists who are users of the existing tradition, not creators. And because of that, black culture in general—which has defaulted into hip-hop—is no longer perceived as an interesting vanguard, as a source of potential disruption or a challenge to the dominant. Once you don’t have a cool factor any longer—when cool gets decoupled from African-American culture—what happens to the way that black people are seen?

Now is the strangest time in American history to be a black person. Never before was it so ambiguously defined. It’s not like someone is telling me “You are 3/5 of a human.” To which I could say “Uhhh, nah.” Most of the time, no one comments on my blackness. But I experienced a deep sorrow and terror looking at pictures of military tanks and the ongoing unrest in St. Louis. Then I remember my skin color is a permanent indicator of social inequities whose resolution has gone down slow for centuries, with all the confusion that can entail. Having access to a legacy of cool is one of the few obvious upsides about being black in America.

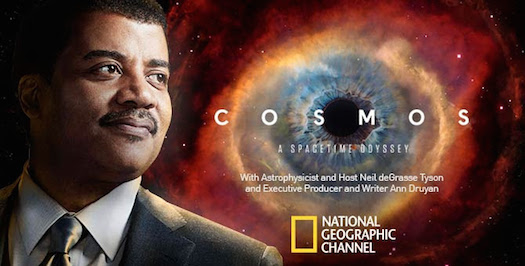

But as social and cultural institutions slowly accept the wide-ranging modalities of blackness, it becomes increasingly complex to understand what constitutes a “black experience,” and how the idea of black cool, as Questlove describes it, plays into that. What to do when there are so many pop rappers who make hip-hop look backward? What to do when the internationally-celebrated Ursula Burns, Gabby Douglas, Neil DeGrasse Tyson, Beyonce, and Shonda Rhimes serve as proof that America is fair and colorblind to oblivious types who want to believe the killings of Mike Brown, Renisha McBride, and Trayvon Martin had nothing to with race?

When President Obama was first elected, I think most people, regardless of partisanship, wanted to believe he’s “tan”: a new color, neither hearty white or lite black, just the color of a beautiful, smart, cool people in a post-racial future. We’ve seen since, though, how Obama’s had to tactfully negotiate his blackness (primarily by ignoring it), in various politically fraught situations over the past six years. This negotiation has been ongoing on so many levels: what he talks about, how he talks about it, and when. Comedians Key & Peele used to do a funny series of sketches about Obama and his anger translator Luther who is a much more “excitable brotha.” Luther is a great example of a blackness that shows itself in the form of extreme entertainment, whereas Obama’s is one of the most idyllic interior cool. The two are presented as opposites that meet on the terms that “Cool is social engagement masquerading as a kind of disengagement.” The juxtaposition of the two men underscores that both are performing for an audience.

Questlove’s inquiries about the state of black cool are largely prompted by the full sublimation of hip-hop into mainstream and white culture, but President Obama has surely played a huge role in making it more acceptable for blackness to coincide with talent and intelligence in arenas outside of athletics and entertainment. As a figure-head, a role model, Obama’s face really does mean more than any president’s talking head ever did. And it goes beyond his meaningful blackness. What may matter even more is that the president’s heaviest connection with the majority of Americans is via media. That relation rarely comes down to politics qua politics. Even if Obama avoids talking about race in a pointed way, his image won’t let us escape it. And social media won’t let us escape the image. Technology, more than any other factor, is responsible for the mutation in the image of blackness and black cool.

You begin to see something in this virtual world that induces despair as you advance in life through any professional field: politics are everywhere, and social media exponentially increase the potency of image-first exchanges. In the cake-baking world, and in the balloon artist community there are virtual politics: the pageantry of making good impressions, of championing ideals that are rarely, truly believed in, the advertising and popularity contests, the “hot and new,” and the fulfillment of obligations for fear of the political (i.e. artificial) consequences of doing otherwise. When politics actually happen in the Political World—the nexus of human rights and conflicts over distribution of limited resources—it seems terrifying, and sort of hopeless. And also meaningless, meaningless, to quote Ecclesiastes. The pervasiveness of social media clarifies how shallow some institutions (and institutionalists) are willing to get, and how shallow many of them already are.

Aside from the constants that make democratic governance difficult, it’s double-trouble for anyone to be President in the age of twitter. It really is too soon to process what it means to have had a black president for two terms. It’s a trip to have entered Obama’s presidency feeling his blackness meant something, and knowing we will exit it feeling it means something else, or (worst case) nothing at all.

I’m having an identity crisis.

Not really. But Questlove’s article got me thinking harder about some questions I had been idly tossing around:

Once you don’t have a cool factor any longer—when cool gets decoupled from black American culture—what happens to the way that black people are seen, period?…Are they seen? That’s not rhetorical.

This is…a point, but it’s not THE point. The bigger takeaway is once you don’t have black cool, do you have ANY cool in America? We are a young country, whose culture, I would argue, is defined by the capital of white people, the erasure of Native people, and the culture of black people born out of a lack of capital. Everyone’s great-grandfather from Italy, or Colombia, or Nigeria and the whole melting pot thing are quaint embellishments to the main narrative. But what has given the United States edge in the world is slavery and all of its legacies. Truly. Black and white Americans are two poles of the same ethnicity, the same history.

Now that this girl exists

With comparable visibility to this man

Having a conversation about appropriation doesn’t really cut the mustard. Iggy Azalea and I are about the same age, so as much as she doesn’t impress me, I also feel her. She is just being a pop musician, which is the most unimpressive thing a person can be today (look at Beyonce, who is visibly struggling, with each performance, to deal with the fact that she cannot impress herself). So it doesn’t matter so much to me if she is a white girl with a fat ass who tries to rap. She’s no different from Rihanna (who has more catchy songs, but is really, besides her unique humanity—which I must give her the benefit-of-the-doubt of having—no different). It’s not like Jay-Z is a wellspring of creative genius and hard-hitting truths. Black people are appropriating black culture…so I’m kind of done with the word appropriation in the context of black and white American pop life.

Neil DeGrasse Tyson is awesome. To the best of my knowledge he rarely talks publicly about race, maybe because like me, he has wanted to avoid giving white people more license to build in limitations (it’s okay for me to talk about white people… I have a lot of white friends). It’s interesting that race is not a big public thing for him. Perhaps that’s because his community isn’t fact-averse, and the fact of who he is as an astrophysicist is undeniable.

THE POINT IS: the question of COOL, which has always been black—and always American—now becomes a kind of existential question. Can it even exist here, anymore? Who will be its vessel? What happens when the people who have been the poster men and women for disenfranchisement for centuries are having highly visible successes, however non-normative they may be, and put in the place of widespread cultural influence across many fields and professions? That is to say, what happens when black people slowly, slowly start to acquire the social and real capital that white people have always had? Does everything go white? Does everything go stale? Does everyone become a square?

In a post-western world, how do we do anything new now that the original novelty of brown people is gradually wearing away? Even going to Mars won’t seem as fresh as stepping on the Moon.

***

As I’ve edited this essay, I realize that cool will probably be okay, but it will certainly evolve like everything else. Questlove’s main gripe is that pop hip-hop is the dictator of mainstream culture. And while this is true of a certain generation, I think that for the same generation, the ascension of black politicians, artists, intellectuals, scientists, executives, and alternative athletes have the potential to bring the power of coolness to intelligence and creativity in a way that we have never seen before. America has hope for a comeback.

From October, 2014