This piece, which Oliver Craner originally posted at his personal website last summer, offers a deep reading of Iraq’s post-invasion trajectory. Craner’s piece isn’t definitive. He gives a little too much credence to canny purveyors of the given such as journalist George Packer. Still, Craner’s account of Kanan Makiya’s journey beats what’s been on offer in most think pieces tuned to the 20th Anniversary of “shock and awe.” I commend, in particular, Cramer’s return to The Rope — Makiya’s own attempt to reckon with what happened in Iraq. The Rope, which refers to the one used to hang Saddam Hussein, tells the story of a Shiite militia-man whose life comes down to one sectarian betrayal after another. The anti-hero of the book — an orphan who looks up to his uncle as more than a mentor — will find out (before the book’s end) the uncle was behind the murder of the militia-man’s father. Iraq in a nutshell? It’s important to add, though, The Rope isn’t simply a fable. As Craner notes, Makiya’s fiction was founded on real events such as…

the murder of Abdul Majid al-Khoei by supporters of Muqtada al-Sadr on April 10, 2003, the day after the fall of Baghdad…Abdul Majid al-Khoei had been a well-connected exile in London and America, a friend of Makiya…with allies in the U.S. and European governments. This was only one reason for his eventual demise in Najaf, but in some ways it was enough. In The Rope, Makiya’s narrator sees al-Khoei dying in a back alley after being stabbed to death at the door of Muqtada al-Sadr’s residence and asks his Uncle, a Sadrist, who he is: “an American agent,” is the reply (45). The role of the Sadrists in the murder of al-Khoei would eventually be covered up by the political leaders of the Shia in Baghdad, the group of exiles who went from the Governing Council to running Iraq and who saw the Sadrists as key to securing their own power. These were men, according to Makiya, who sacrificed Iraq to sectarian war in order to secure their own futures, and the cover-up of al-Khoei’s murder was a key part of this.

The al-Khoei episode in The Rope is one of many moments in Makiya’s true-life novel that provide glimpses (per Craner) “into the dark world of betrayal and conspiracy that confounded the Americans during their years of occupation…” The Rope is Makiya’s attempt to separate the dark from the dark. His clarities — “Iraqi mistakes are orders of magnitude more important to what has gone wrong in Iraq than American mistakes” — never reduce to a ruse to slip his own responsibility. He’s apologized to the Iraqi people for willing them to believe in the good faith of his former allies in the “democratic” opposition to Saddam Hussein (who went on to preside over the ongoing disaster in-country) and he’s admitted: “I can’t look into the eyes of a woman, from Oklahoma or somewhere, who has lost her son and tell her that her son’s death was justified. I can’t do that.” Yet he remains convinced that removing Saddam was morally correct…

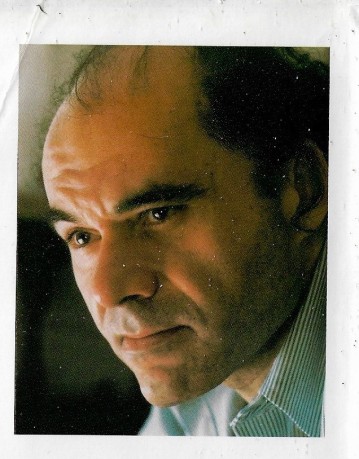

Archives of Pain: Kanan Makiya and the Politics of Iraq

That’s the hope I still have for Iraq — that it can rediscover its destiny as a richly various and pluralistic society, a meeting ground of all sorts of creeds and groupings. That’s the hope that sustains me.

Kanan Makiya, 1992 (1)

There is no political power without control of the archive, if not memory. Effective democratisation can always be measured by this essential criterion.

Jacques Derrida

I: Sweets and Flowers

By the end of 2004, Kanan Makiya was beginning to lose hope. “My realisation, in late 2004, that Iraq was sliding toward civil war was a turning point in my life,” he wrote at the end of his 2016 novel, The Rope:

The whole edifice of hopes that had clung to that slim possibility of a different kind of transition from dictatorship crumbled. Self-doubt began to eat away at the optimism that had sustained me since 1991. (2)

That optimism had been both a source of strength and a liability. Makiya made plenty of enemies in the early 1990s, but even friends and allies would comment on the rather unreal quality of his idealism and expectations for Iraq. Ali Allawi, Iraq’s first Finance Minister after the fall of the Ba’ath, dismissed his “solitary path in a campaign to mobilise Iraqis in exile behind a post-modern, somewhat ethereal, vision of a tolerant and pluralist Iraq” (3). George Packer, in his chronicle of the Iraq war, saw “more than a little naïveté in Makiya – a worrying trait, given the project he was about to sign on for” (4). Fellow Iraqi exiles and friends who had returned to Baghdad at the same time and with some of the same illusions soon found his persistent talk of democracy and liberalism in a country that was disintegrating around them exasperating. One told Packer: “Kanan is living on another planet. He doesn’t have a clue. He drives to the Green Zone and back to the hotel” (5).

Kanan Makiya had a vision – but he was almost alone. In one way, Allawi was correct: within the exile community he cut a rather ethereal figure among the ex-Ba’athists, Shia clerics and Kurdish politicians who had their own ideas about what Iraq would look like after Saddam. Makiya was a secular liberal with a rather refined political disposition formed by his late discovery of “Hannah Arendt…Isaiah Berlin, John Stuart Mill, Hobbes” (6) while writing Republic of Fear: The Politics of Modern Iraq during the 1980s. When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, Republic of Fear became an overnight bestseller; in 1990, it was one of the few books that existed in any language providing details of the highly secretive and brutal regime that was now making global headlines. In the fractious world of post-Gulf War exile politics Makiya joined Ahmed Chalabi and the Iraqi National Congress (INC) in making the case — and actively working for — regime change in Iraq. When Makiya agreed to join other Iraqis on the State Department’s futile Future of Iraq planning group in 2002, he effectively took over the project and proposed a new model that would represent all of Iraq’s clans, tribes, ethnic groups and religious sects in a pluralist democracy built by the Iraqis themselves. He then pursued this dream with an obsessive and even arrogant idealism that offended and alienated his fellow exiles, hence, perhaps, Allawi’s curt dismissal.

Given the factions that developed over Iraq it was perhaps inevitable that Makiya would become a partisan in the fierce civil war that broke out inside the Bush administration after 9/11. This period of internal conflict provided a key to the enigma of the 2003 war and Makiya had his own view on it: “the Department of State was seeking change from within the Ba’ath regime, not from without by means of the organised Iraqi opposition. Regime change led by former Ba’athists was their way to the future…it was about regime change without democracy” (7). In this context, he acquired Chalabi’s allies instead: a neoconservative faction located in the Department of Defence and the Vice President’s office that had been engaged in ideological hostilities with the State Department for decades. This set up a deadly contest that both drove and derailed U.S. strategy: “deep internal American conflicts hobbled the whole enterprise from the outset,” Makiya later claimed, “matters reached the level of hatred between and among Americans…the warfare at the heart of the Bush administration was shaping the agenda rather than any positive plan.” The post-Saddam collapse had its root in these departmental hostilities and bitter personal feuds at the top of the administration — in effect, factional schisms within Washington’s foreign policy elite helped set the stage for an explosion of sectarian hatred in Iraq.

But, as Makiya was always at pains to point out, these divisions predated the American intervention and it was the Iraqis themselves who chose to go to war with each other after 2003. Responsibility and agency were central to his views on the region and on human nature. His optimism had always been tempered by realism; his political world had, after all, been shattered by the twin disasters of Khomeini’s terror and the Lebanese civil war. He knew all about the dangers of sectarianism and political mythology in the Arab world. He had seen his old comrades on the secular Arab left defeated by their enemies, former allies and, finally, their own degraded political culture:

We were locked in the dynamic and the language of the Lebanese civil war. Issues of human rights, of building civil society, of dictatorship, of our own responsibility for our own ills, were all constantly being subordinated by the old language of anti-Zionism and anti-Imperialism. I had come along with Republic of Fear and said the most important thing is what we have done to ourselves. I was bending the stick, as we say. Many Arabs, and people on the left who identify as ‘pro-Arab’, objected. (8)

This was not always what people wanted to hear. When he applied this experience to Iraq in 1993’s Cruelty and Silence: War, Tyranny, Uprising, and the Arab World (9) he made powerful enemies among the political and cultural elites of the Middle East (albeit not among the Iraqi exiles themselves). In this book he had exposed their silence when confronted with Ba’ath violence and totalitarianism, a silence that provided political cover for Saddam’s crimes in Kuwait and Kurdistan. Considering the fate of Iraq itself — outside of the rhetorical prison of pan-Arabism — he saw one solution: the removal of Saddam by the only power that had unequivocally defeated him and could apply the force required to destroy his regime. This was a sin against Arab solidarity and honor: a taboo only the most desperate of Saddam’s enemies had been willing to break. It would end in the Oval Office, with Makiya assuring Bush and Cheney that American troops would be greeted with “sweets and flowers” in Iraq.

For Makiya, the 2003 war was — and remains, despite its failure — a war to liberate Iraq from Ba’athist tyranny. Like the Iraqis he wrote about, his past and his politics had been shaped by suffering and pain. His writing was a response to this; a way to understand and overcome it. His original Iraqi trilogy — Republic of Fear, The Monument and Cruelty and Silence — was the work of a dedicated archivist: a collector of documents, stories, pictures and videos that detailed a history of Ba’athist violence and terror. The work on Republic of Fear began with his own files, a substantial collection even by the mid-1980s. This was later supplemented by material uncovered in public libraries; SOAS at first, and then the New York Public Library, where he discovered a surprisingly large cache of Ba’ath pamphlets and documents. The Monument grew out of his father’s rich collection of architectural records which allowed him to enter the cultural life of Iraq both before and during the Ba’ath era, recovering a legacy of riches that would be tragically subordinated to the totalitarian propaganda of Saddam. Finally, the success of Republic of Fear made Makiya a recorder of testimony, as the regime’s victims sought him out and told their stories. These were collected in the first part of Cruelty and Silence, a work that planted the seed for his final archival project: the post-war Iraq Memory Foundation.

This vast and fragmented archive of pain formed the basis for all of Makiya’s early work. It also shaped his view of Iraqi Ba’athism as the apotheosis of pan-Arab nationalism and an heir to Europe’s totalitarian parties and movements. This legacy found its ultimate expression in the destruction of pluralism in Iraq: a pitiless campaign waged for decades by pan-Arabists and Ba’athists against ethnic minorities, religious sects and independent political parties. Makiya was able to use the archival records at his disposal to reclaim political power on behalf of these victims; this was, in the end, the only way to reclaim the integrity of past experience and the meaning of memory.

II: Republic of Fear and Arab Nationalism

In the early 1990s, writing in Cruelty and Silence, Makiya noted an “upsettingly common reaction” among Iraqi Arab readers of Republic of Fear: “Why did you give so much space to the plight of a handful of Jews in 1968? Didn’t every Iraqi suffer?” (10) The answer was obvious, and important: how the regime treated its most vulnerable minorities revealed how it would treat all of its citizens in time. When Makiya began to analyse the ‘World of Fear’ constructed by the Iraqi Ba’ath party after their seizure of power in 1968, he took special note of the fate of the remaining Iraqi Jews. Specifically, he focused on the execution, in January 1969, of 14 people accused of spying for Israel: 9 of those hung in front of cheering crowds in Liberation Square had been Iraqi Jews, which sent an unmistakable message to those who had not already fled the country. This was the grand opening of a new Iraqi pogrom organised by the Ba’ath — the pan-Arab party par excellence — who proceeded to arrest and torture over one hundred more ‘Israeli spies’ and create a climate of fear that led to the final mass exodus of Jews from Iraq.

The destruction of Jewish life in Iraq left a hole at the heart of the Iraqi state. Over centuries — from the time of the Babylonian captivity — exiled Jews had established successful communities in Mesopotamia and, after the First World War, they helped to build the modern Iraqi state out of the ruins of the Ottoman empire. This experience secured their national identity and ensured that Zionism did not have a broad constituency, but with the increasing power of Arab nationalism and waves of Jewish immigration to Palestine, Iraqi Jews would eventually be accused of “Zionism” whatever their views or allegiances. In the end, it wasn’t the Jewish state that destroyed Iraqi Jewry, but the conspiratorial and antisemitic pan-Arab ideology that found a home in the military regimes that would eventually rule Iraq. The first Jewish pogrom in the modern Middle East occurred in Baghdad, encouraged by the pan-Arab allies of the Axis powers; the 1941 Farhud was an explicitly Holocaust-related event, incited by Nazi propaganda and pro-fascist militias. Successor pan-Arab regimes and parties would finish the job, not only in Iraq but in states across the Middle East and North Africa: 850,000 Jews fled these countries after 1948, driven out by the antisemitic campaigns of pan-Arab forces.

This legacy would prove to be a useful and powerful weapon in the hands of the Ba’ath. It provided them with a model for persecution and control; as Makiya noted, the “anti-Zionist” campaigns of 1968-70 “turned out to be the thin end of the wedge in a generalized campaign of terror that finally touched every Iraqi” (11). The ascendancy of pan-Arabism in Iraq, whoever was leading it, would always be linked to ethnic persecution and violence: pan-Arab army officers effectively cut their teeth during the Simele massacre of Assyrians in 1933 and the Farhud directly followed the overthrow of the pro-Nazi regime of Rashid Ali al-Gaylani. Ba’athism itself sought unity in its own pan-Arab ideology; it abhorred diversity and individualism, both philosophically and as a practical threat to its authority, which had to be total. The Jews were the most powerful and visible ethnic minority in Iraq and so they became a symbol of the very pluralism that had to be eradicated to forge a pure Arab identity. If, as Makiya claimed in Republic of Fear, “the essential core of Ba’athism is pan-Arabism” (12) then Ba’athism became, in effect, an Arab nationalist project to overcome the “embedded social pluralism” of Iraqi society.

The centre of Iraqi pluralism was its capital. During the period of the British mandate and the Hashemite monarchy, Baghdad became a vital regional metropolis, an ethnic and cultural mosaic with the liveliest local nightlife outside of Beirut. In the midst of this creative chaos, the ideology that would ultimately destroy the city’s pluralism also found its voice with the appointment of the pan-Arab nationalist Sati al-Husri as Iraqi Minister of Education in 1920. Living in Baghdad, he observed the city’s culture of tolerance and diversity with disgust and wrote a new school curriculum that was designed to eradicate its cosmopolitan, multi-ethnic reality. In her family memoir, Late for Tea at the Deer Palace, Tamara Chalabi described the experience of her uncles in al-Husri’s schools during the 1930s:

Both Rusdi and Hassan noted with great unease how their school had become more militant and overtly nationalistic in its teachings, as had other schools. During morning assemblies, the boys winced as the school anthem kept changing, with more aggressive language being added to its verses. Their history books were full of alienating references to those who weren’t Arab Sunni, and all the students were encouraged to undergo military training…It was an uncomfortable atmosphere that, they felt, pushed each person towards his basic sectarian or religious identity. (13)

Like all such movements, including Ba’athism, al-Husri’s pan-Arabism proved to be narrowly sectarian in practice: he wasn’t just antisemitic, but also despised the Shia and successfully barred their entry to higher education and teaching posts, much to the chagrin of the ambitious Chalabis.

It is important to understand the philosophical origins of al-Husri’s version of pan-Arabism in order to understand where it ended up and to fully grasp the scope of Makiya’s dissection of the Ba’ath in Republic of Fear. The nationalism of al-Husri and his disciples — which included Michel ‘Aflaq, one of the founders of Ba’athism and the hero of its Iraqi variant — was a reactionary, populist and aggressive creed rooted in the traditions of German romanticism and cultural nationalism. Inspired by the writings of Johann Gottlieb Fichte, al-Husri called for the foundation of an Arab nation unified by a common culture, language and historical heritage. This had nothing to do with the liberal models of British parliamentary democracy or the French state; it was, in fact, directly opposed to these traditions. What al-Husri had in mind was an “organic” Arab nation that was exclusionary and authoritarian and superseded the mere political structure of nation states. Observing the fragmented, polyglot countries of the Middle East and North Africa during the 1930s, he had decided that what the Arabs really longed for was an “Arab 1871” – as if pan-Arabism was a regional parallel to pan-Germanism, then being pursued by the Third Reich. Pan-Arab nationalism was the movement that would restore the “glorious Arab past”, something that seemed distant and remote in the corrupt, cosmopolitan reality of modern Baghdad. It was al-Husri, wrote Bassam Tibi,

who began this tradition of populist germanophile Arab nationalism. His nationalism was not mystificatory, fanatic or fascist, but he laid the foundations for the kind of fanatical nationalism formulated by his disciple Michel Aflaq, which…found expression in the semi-fascist military dictatorship in Iraq and Syria under the aegis of the Ba’ath party. (14)

In Republic of Fear, Makiya devotes considerable space to Iraqi pan-Arabism and the pan-Arab roots of Ba’athism: in effect, the book shows how a movement founded by “the Arab Fichte” culminated in the “Arab Prussia” of Iraq’s military and Ba’ath regimes. Makiya saw Ba’athism as the logical conclusion of pan-Arabism and, for this reason, his project ranged beyond the specifics of Saddam’s regime to launch an even more ambitious attack on the very ideology that had captivated the Arab nations and led to their ruin.

This had a key place in Makiya’s own biography. In 1967, as an Iraqi college student with an English mother, he had listened to BBC broadcasts during the Six Day War and learnt about the destruction of the Egyptian air force while his classmates were still digesting reports of Arab victories on Baghdad Radio:

All lies and bullshit. And I remember knowing that it was bullshit at the time. I had my first political discussion with young men and women of my age in Baghdad, at a public swimming school where we gathered. I said, ‘it’s lies, it’s lies, it’s not true.’ The Arab world was losing the war, superfast, but there was this denial. And ordinary people only had what the regular news was saying. I remember being infuriated by that obvious lie. (15)

Makiya was successfully inoculated against Arab nationalism by this experience. The Six Day War was a defeat that destroyed the pan-Arabism of Nasser but it did not die completely: it found a new, more brutal form in the Ba’ath regimes of Iraq and Syria. Republic of Fear was the book that rooted Ba’athism (and the dictatorship of Saddam) in the ideology and lineage of pan-Arabism and therefore held the “lies and bullshit” of 1967 to account.

For Makiya, the legacy of Arab nationalism was military dictatorship, secret police states, antisemitism and ethnic cleansing. The pan-Arab regimes of the Middle East and North Africa had destroyed their ancient Jewish communities while fostering a seething underground of religious and ethnic sects, movements, parties and militias that would, eventually, rip the entire region apart. The Jews of Iraq once found hope in the development of Iraqi nationalism, in which they felt included, but fell victim to the triumph of pan-Arabism, an ideology that would gain coherence and strength through their exclusion, persecution and, finally, expulsion. The ultimate enemy of the pan-Arabists was Iraq’s social diversity and their target was its parliament. “In practice,” wrote Makiya,

the Iraqi parliament before 1941 was astonishingly vibrant as a mechanism for drawing out individuals from their communities. It was, moreover, the only institution responsible for inculcating and symbolising the true breadth of societal freedom – typified by a completely open press – in which every shade and current of opinion, however bizarre, resonated. (16)

To the pan-Arab imagination, however, the Iraqi parliament was a symbol of everything they hated: the messy diversity of representative politics, which undermined the unity and strength of the Arab nation. From the pro-Axis coup of 1941 to the butchery of 1958 and the successive nationalist and military regimes that followed, the war on pluralism intensified in the name of pan-Arabism, finding perfection, finally, in the Ba’ath machine of terror.

Ba’athism, in theory and practice, could not tolerate diversity. Pan-Arabism could only work – could only succeed – by defeating local nationalisms (Iraqi, Syrian, Egyptian) and by subjugating all other forms of identity, whether tribal or confessional or political, to its own unitary identity. As Makiya illustrated, for Ba’athism, the final exemplar of pan-Arab politics, “the only freedom that is logically possible is the freedom to act as one with the mass, and be sacrificed to its cause” (17). This, ultimately, is the significance of the root of Ba’athism in pan-Arabism and the roots of pan-Arabism in German nationalist thought: here, the road also led to totalitarianism and genocide. Iraqi Ba’athism was “consistently egalitarian in its hostility to everything that is not itself,” (18), Makiya would write. Its idea of freedom was “total unity” which meant, in practice, the “obliteration of separateness, privacy, independence, difference, autonomy, variety, character, and personality” (19). Michel ‘Aflaq, the true philosopher of Ba’athism, had originally described the essence of the party as “love” and “faith” in the “Arab Spirit”, but the other side of this was a pure hostility to the enemies of Arabism. The Ba’athists proved to be great haters and the Iraq they created would be defined by fear, suspicion, violence and revenge. This would find apotheosis in a speech delivered by Saddam Hussein in 1978, which warned:

the revolution chooses its enemies, and we say chooses its enemies because some enemies are chosen by it from among the people who run up against its program and who intend to harm it. The revolution chooses as enemies those people who intend to deviate from its main principles and starting points. (20)

This was the ultimate politics of exclusion, something beyond Arab supremacy but also rooted in it, a statement that certified inclusion through loyalty to the principles of the Ba’ath, and therefore the ‘Arab Spirit’, a loyalty that would nevertheless be judged by the party, or the leader, on an arbitrary basis. It was a formula for mass murder.

III: The Monument and Totalitarian Art

In the spring of 1980, Mohamed Makiya received an offer he could not refuse.

This was the first year of Saddam Hussein’s presidency and the new dictator was looking forward to hosting the Conference of Nonaligned Nations, an event that would inaugurate his leadership of the movement for the following three years. To prepare for the occasion, Saddam decided to completely renovate his capital city. He gathered his aides and asked who, among all the remaining Iraqi architects, would be up to the challenge of redesigning and rebuilding Baghdad in the space of two years. There were only two candidates with the required experience and skills: Rifat Chadirji, who was in jail, and Mohamed Makiya, who was living in exile in London, having fled Iraq after being included on a Ba’athist blacklist in the early 1970s. When Makiya was first offered the project, he refused, but the second approach, made with an assurance of “safe return” (“the most chilling part,” his wife Margaret would note), was too dangerous to refuse. Also, for an architect born in Baghdad, the commission itself was simply too tempting to turn down. Makiya was being offered the chance to reshape the city of his youth, the second Arab city of the modern era, the old capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, the heir to Babylon itself. Really, the Ba’athists seemed like a detail of history compared to this.

After the Iranian revolution and with Islam on his mind, Saddam had been impressed by Mohamed’s redesign of the Khulafa mosque in central Baghdad, an early masterpiece that encapsulated the architect’s fusion of the International Style and Mesopotamian vernacular. “Who did this?” asked Saddam, and the answer he was given would play a part in Makiya’s later commission. Back in Baghdad, working alongside his old friend Chadirji (now released from prison), Makiya was drawn further into the Ba’ath project to redesign the city, inspired by the historical dimensions of the task. His son, Kanan, who remained in London to manage Makiya and Associates on behalf of his father, did not approve. “I said we shouldn’t be doing this,” he explained in 1992,

We just shouldn’t be doing it. My father would answer, ‘This is for history. It’s not for the people there now. It has nothing to do with them – they’ll be gone. This is for Iraq – it’s for the future.’ And, in a way, in all this he was simply being consistent with his usual approach: he always showed total disdain for the client – because he wasn’t doing this for them, it was always for the future. Architects are such megalomaniacs. (21)

Mohamed Makiya was born “when the British entered Baghdad” in the words of his mother — although, as Kanan remembered it, nobody ever really knew if she meant 1914 or 1918 (22). He was from the old city. “It was like the Middle Ages,” he recalled decades later, in London:

I wouldn’t have to read about a medieval city because I lived it. There was no electricity, no water, no sanitation. I’m very much influenced by it. I’m deeply Baghdadi, and I’ve been thinking of Baghdad all my life. (23)

After graduating from the School of Architecture in Liverpool and completing his PhD at Cambridge University, Makiya returned to Baghdad in time to benefit from Iraq’s newly revised oil concession in the 1950s. With money pouring into government accounts, the Iraqi Development Board hired newly qualified Iraqi engineers and architects to redesign and rebuild the capital. Prestige projects with big budgets lured the most famous architects in the world to Iraq. Walter Gropius was asked to design the new University of Baghdad, where, in 1959, Makiya would found the School of Architecture that he led for over a decade. Le Corbusier was offered a sports complex (destined, one day, to be the Saddam Hussein Gymnasium), Alvar Aalto the national art gallery, and Frank Lloyd Wright completed his visionary, but unrealised, Plan for Greater Baghdad, which included an opera house on the banks of the Tigris. They were all guests in Makiya’s home and he would later recall driving a “very bossy” Wright around Baghdad in his car.

Mohamed was a witness to the cultural and political revolutions that overtook Baghdad from the 1950s through to the 1980s, and participated in some of them. The period between the Second World War and the 1958 coup was a cultural golden age for Iraq and gave birth to an artistic and literary renaissance in Baghdad. This was the moment a generation of postwar Iraqi intellectuals came of age, influenced by communism, modernism, existentialism and liberalism, as well as Arab and Iraqi nationalism. In the Baghdad public library and the cafes and bookshops of Rashid Street, artists, writers and politicians debated Marx and Sartre and the Arab revival, formed new societies, rival parties, political alliances and personal enmities. This was the city that gave birth to the first free verse movement in the Arab world and produced a deluge of newspapers, journals, poems and novels that rivaled the output of Cairo and Beirut. Thriving cinemas, first introduced by the British in 1917, fed the Iraqi hunger for Hollywood films, while theaters, clubs and concert halls contributed to the city’s vibrant nightlife. Glamorous Iraqi chanteuses — like the Armenian ‘Iraqi Blackbird’ Affa Iskandar and the Baghdadi Jew Salma Mural (‘The Voice of Iraq’) — found fame across the Middle East and North Africa. In Late for Tea at the Deer Palace, Tamara Chalabi described family memories of a city “filled with music and verse” at this time:

In the small cafes in the old neighbourhoods, gramophones blared out Egyptian love songs and Iraqi melodies, increasingly performed by female singers. The music of Iraq catered for all tastes: there were popular tunes, Bedouin songs, gypsy songs, songs sung in falsetto by men dressed as women, women’s bands for female social occasions, the dirges of official mourners, religious music, the songs of labourers – ranging all the way to the more formal and elegant maqam that held a unique position in the high music of the region. (24)

The city’s nightlife was dominated by the Baghdadi Jews, who, along with the Christians, owned most of the clubs, concert halls and cinemas, primarily because of an old Ottoman convention that forbade Muslims from acquiring entertainment licences. Mohamed Makiya was part of this Baghdad, and the redesigned Khulafa mosque was his first and most significant contribution to its landscape. All of his big commissions from later years – the mosques and ministries and private residences in Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar and UAE – built on what he had achieved in Baghdad in 1963.

When Kanan began to write The Monument, his second major work, Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait had not yet happened and Republic of Fear was only being read by regional specialists and Iraqi exiles. The project had been completed alongside a lavish monograph on his father’s work (Post-Islamic Classicism, 1990) and both books, in different ways, touched upon a similar theme: the achievements and failures of a postwar generation of Iraqi intellectuals. At the centre of The Monument stood the pioneers of Iraqi art from the ’40s to the ’60s and their productive dialogue between tradition and modernism: architects, sculptors and painters like Rifat Chadirji, Jewad Selim, Khalid al-Rahal, Mohammed Ghani and, among them, mixing modernism and Islamic tradition, Mohamed Makiya. “Largely through their efforts,” Kanan wrote,

Baghdad became in the 1950s the centre of some of the most dynamic and original experimentation in the visual arts anywhere in the Arab world. Certainly in no other Arab country did visual talent cohere into such a powerful, self-reinforcing, particular way of looking at felt reality, rooted in Iraqi experience. An indisputably Iraqi way of thinking about the plastic arts came into being, made up of talented, opinionated and generally very productive individuals knocking against each other, yet springing out in different directions. (25)

This lasted longer than the monarchy but it didn’t last any longer than the final Ba’ath coup. Until then, the nationalists had some use for the modernists and gave them some latitude: Jewad Selim’s Freedom Monument, a complex bronze mural influenced by Picasso and completed in 1961, was originally commissioned by Qasim to extol Iraq’s republican revolution. It still stands in Liberation Square and provided an ironic and tragic backdrop to the anti-Zionist lynchings of 1969.

Makiya would describe the Freedom Monument as the last legitimate product of Iraq’s cultural renaissance as well as the last large-scale public art work to be attempted in Iraq until al-Bakr and Saddam’s Baghdad development plans. As such, it presented “a kind of bridge between the Baghdad of the 1940s where a remarkable artist achieved artistic maturity, and the Baghdad of the 1980s” (26). The second renovation of Baghdad was, ultimately, Saddam’s project, driven by his determination to construct a new Iraq and to shape the new Iraqis who would serve it. This is the moment that aesthetics and totalitarianism fused, a moment Mohamed chose to participate in. He wasn’t alone: as Kanan noted, Baghdad at this time was a major testing ground for postmodern architecture as the regime used the resources provided by Saddam’s nationalisation of oil to rebuild the city. In an echo of the oil-driven rebuilding of the 1950s, the greatest architects in the world were invited to enjoy the spoils and did so without any obvious reservations. “Overnight Baghdad became a giant construction site,” wrote Makiya

new and wider roads, redevelopment zones, forty-five shopping centres in different parts of the city opened to the public by 1982, parks (including a new tourist centre on an artificial island in the Tigris), a plethora of new buildings designed by Iraqi and world class architects, a crash programme for a subway system, and many monuments – all were put in hand. (27)

The transformation was not just cosmetic, but also ideological – an attempt by the regime to “translate the collective force of the Iraqi people…into symbols” (28). By this point, “the Iraqi people” had been fully excluded from the public realm and the regime no longer permitted them to exist as individuals: their worth was measured as a mass, a collective body at the service of the Ba’ath revolution and pan-Arabism. Something in Ba’athism still aspired to mass politics as George L. Mosse understood it: a civic religion with its own myths, symbols, rituals and monuments. This new Baghdad was not built for people as individuals: it was a landscape of power.

As the money poured in and the regime further degenerated into a tribal fiefdom, the city also became a landscape of vulgarity and kitsch. An emblematic project of this era was the 1982 competition for a new Baghdad State Mosque, a colossal commission intended to challenge Khomeini’s claim to lead the Islamic world. Mohamed Makiya’s entry was monumental, as it could only be, but made direct reference to the Abbasid tradition; likewise, the Japanese architect Minoru Takeyama took inspiration from the original circular plan of Baghdad and the Great Mosque of Samarra. But for Kanan Makiya the most interesting and apposite entry was submitted by Robert Venturi who presented a design that resembled “something out of Disneyland crossed with the scenery from Errol Flynn’s film, The Thief of Baghdad” (29). Venturi’s veneration of kitsch, irony and populism found a new and appropriate place in the Baghdad of Saddam’s imagination. For Makiya, he became an emblematic figure — a patron saint of totalitarian kitsch — but there was nothing that Venturi could say or do to compare to the brutal vulgarity of the Victory Arch, commissioned and partly designed by Saddam with monstrous bronze replicas of his arms and piles of helmets collected from the corpses of dead Iranian soldiers, or the Mother of all Battles Mosque with its minarets shaped like Kalashnikovs. Makiya’s next question was key:

What would have happened had Venturi’s mosque been built in the city of Saddam Hussain’s monument? In place of art, ugliness – which Venturi wanted to extol – has acquired a meaning that he never intended. Thus although the vulgarity of Saddam Hussain’s monument takes it out of the realm of art, in the end by playing this game, the President defeats art. (30)

The portrait of the Iraqi intelligentsia presented in The Monument was, finally, a study of defeat: the defeat of individuals condemned to death or incarceration (like Chadirji), exile (like his father) or compromise (like Khalid al-Rahal and Mohammed Ghani Hikmat who helped Saddam design the Victory Arch). This was the difference between the 1940s-50s – a time of experimentation, modernism, pluralism and relative tolerance – and the 1980s, the Iraq of Saddam and his internal empire of totalitarian kitsch. Apart from the landscape of power he planned for Baghdad, with its superficial veneer of prestige lent by international celebrities, the aesthetic reality of Iraq in the 1980s and 90s was a banal wasteland of presidential portraits staring out from wristwatches, billboards, posters statues; sickly murals of Saddam as a modern day Saladin, riding a white horse destined to liberate the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem; the nouveau riche excess of his gold and marble palaces; or the gangster chic of Uday and his high rolling security detail. This was an aesthetic of conspicuous wealth and raw power to which the surviving artists and writers of Iraq were forced to submit their talents.

All of this was the outcome of 1958 and the dreams and hatreds of pan-Arabism taken to a logical extreme. “Romanticism in art and romanticism in politics met in Iraq in the shape of the twenty-year-old Ba’thi regime,” wrote Makiya, and in many ways this was the final, degraded aesthetic residue of al-Husri’s Germanophilia (31). Successive military regimes, increasingly in thrall to pan-Arabism, shrank the space between politics and culture so that “culture itself as an aloof, professional and critical enterprise began to give way to propaganda” (32). The immediate requirements of ideology and power combined in the goal of “unity” which was reached by a pitiless war against pluralism partly fought in the realm of aesthetics. “The idea of unity,” wrote Makiya,

played the same metaphysical role in Arab culture as the tradition of organicism and a return to nature in romantic Western thought. In both, an illusory hunger for wholeness is at work, originating in a deep hostility (albeit contradictory) to the pluralistic, fragmented, schizoid, individualised nature of modernity. (33)

To achieve this aim of unity, Saddam became a myth-maker – an “artist-President,” to use Makiya’s phrase. This myth-making had many objectives: to extol the Iraqi masses, to serve the Ba’ath revolution, to unify Iraq under Ba’ath rule, to promote the cult of Saddam, to elevate Iraq’s role as leader of the pan-Arab revival and to serve the basic requirements of war propaganda. Like Mussolini and Hitler, Saddam took a keen interest and even active involvement in the cultural productions of his regime. Projects like the Victory Arch or the regime-financed 1983 film Clash of Loyalties – a truly unique attempt to produce a homegrown David Lean-style epic about the 1920 Revolt starring Oliver Reed (who spent most of his time in Iraq extravagantly drunk or having sex with his teenage girlfriend at the Al Mansour hotel) – were as intrinsic to Saddam’s regime as internal terror and regional war. Personal proclivities were not as important here as the question of control:

To find, as in post Ba’athist Iraq, boxes of file containing hundreds of pages of correspondence from the Office of the President providing guidance on the minutiae of wall posters and paintings and murals and monuments made in Baghdad under Saddam, even as he was waging wars with Iran, Kuwait, and the United States: this is the true measure of totalitarian culture…(34)

But the notion of Saddam as an “artist-President” went deeper than his interest in aesthetics and propaganda: if Saddam was an artist, then his raw material was the Iraqi people. Like Italian Fascism and Soviet Communism, Ba’athism, from Aflaq through to Saddam, had strived to create a new mass man: a new Arab, an ideal Ba’ath subject. And like Mussolini contemplating his raw material of lazy, pasta-eating Italians, Aflaq’s dream ultimately led him to despair:

the perfection of his ideal Arab…made him recoil from the real Arabs all around him. Here were ordinary people, who, like the rest of us, had their foibles, prejudices, and simple wants and desires. These filled ‘Aflaq with contempt, a condition bordering on hate. (35)

Late Ba’athism, in particular the party of mass terror perfected by Saddam, was made of stronger stuff: torture would become a tool to “reform” and “mold” people. “When the Ba’ath talk about the “new man” and the “new society” they wish to create, these are not metaphors,” Makiya observed in Republic of Fear:

The objects of torture are not criminals but sick patients or morally incomplete individuals whose deviancy lies in the subjective realm, rather than in concrete transgressions. Torture goes about fashioning them anew, and if death is a frequent result, at least somebody cared enough to try. (36)

Ba’athism was a permanent revolution, “a dream of change”: “their programme is not to win over the masses, but to change them” (37). In this programme, the individual did not matter because society, represented by the state, owned by the Ba’ath, with Saddam as its ideal, took priority over the individual, who represented, if anything, an atomised enemy of Iraqi unity and the pan-Arab revolution.

Except, of course, the individual did matter, precisely as this enemy, which Ba’athism needed in order to define itself. As Makiya wrote in Cruelty and Silence (at the very moment the regime’s programme was disintegrating in the aftermath of the Gulf War): “Saddam Hussein invents and reinvents his enemies from the entire mass of human material that is at his disposal” (38). At some point, the purpose of the Ba’ath party in Iraq went from moulding the new man and the new society to engineering a unitary state that would protect and project its own power. This was the moment when Saddam’s regime, which had partly transcended sectarian divisions, became the principal agent of sectarianism. Torture and individual executions escalated to ethnic cleansing, genocide and ecological destruction. Baki Sidqi’s massacre of Assyrians of 1931 showed that Iraqi pan-Arabism already contained the seeds of ethnic mass murder, but it was the Ba’ath who turned mass murder into an art form in Iraq. The ‘Arabisation’ of the north, partly achieved through dispossession, forced migration, the destruction of villages and chemical extermination, was an attempt to permanently change regional demographics by displacing the Kurds and Assyrians. From the perspective of the Ba’ath this was not simply revenge, but a technical solution to a political problem. This existential, ethnographic project had its sequel in 1993, when Saddam chose to solve the problem of Shia militias in the south by draining the marshes and destroying the ancient communities and culture of the Marsh Arabs. This was another creative, technical response to a purely political problem, and on a grand scale: the construction of dams, dykes and the realignment of the Tigris river banks was a vast civil engineering project designed to achieve a new demographic and political reality. Such a monstrous scheme could only succeed in a state ruled by a tyrant with total control of resources, decision making, military capability and internal security.

Ultimately, the draining of the marshes had the same political and philosophical root as the redesign of Baghdad undertaken by Mohamed Makiya and his colleagues in the 1980s. Saddam, the artist-President, used all the tools at his disposal in the attempt to create a unitary Iraqi state in line with the ideology of the Ba’ath, the dream of pan-Arab revival and the projection of his own personal power. In order to build this new society, art, architecture, engineering and propaganda served the same end: the destruction of pluralism, democracy and freedom.

IV: The Rope and the Shia

In January 2007, a battle took place between U.S. forces and an obscure messianic Shia sect called Jund al-Samaa’, or the Soldiers of Heaven. The Americans had been told that the group would use the ceremonial procession of Ashura to attack the holy city of Najaf and massacre its grand ayatollahs. Jund al-Samaa’ believed it was their duty to hasten the return of the Hidden Imam and the Day of Judgement by fomenting chaos and insurrection, but in a matter of hours they were wiped out by U.S. airstrikes and raids on their camps. In The Rope, Makiya’s narrator — a young Sadrist — blames the father of his best friend for their demise:

A great mystery surrounds this operation, but it later transpired that the Americans were acting on false information supplied by the House of Hakim. Uncle believed the villain was Abu Haider; he had fabricated a claim, backed by his friend the governor of Najaf, a man also from the House of Hakim, that the Soldiers of Heaven were a Shia offshoot of al-Qaeda; and the credulous Americans believed him, even though everyone else in Najaf knew this was nonsense. Why the Occupier did not know these things, and was so wasteful of his own military resources, is a mystery only known to God. Mercifully, Haider, who was in the habit of relaxing and unwinding in their company, was not visiting the camp at the time of the air strikes. Several hundred harmless innocents were killed in a matter of hours – men, women, and children. Afterward, everyone – the Americans, the House of Hakim, and the government – colluded to cover up the outrage. (39)

In his personal note at the end of the novel, Makiya returned to the subject:

I had access to a detailed Iraqi police report written in the immediate aftermath of the attack, replete with pictures, smuggled to me by an Iraqi security officer who was one of the first to visit the devastated area after the event. I do not know if the Americans knew what they were doing, and I am inclined to agree with Iraqis on the ground who told me they were tricked into it by Shia enemies of Jund al-Samaa’. (40)

This episode — and Makiya’s description of it — provides one small glimpse into the dark world of betrayal and conspiracy that confounded the Americans during their years of occupation. According to the account presented by Makiya, the Soldiers of Heaven were not simply victims of American arms: their corpses were the collateral of intra-Shia rivalry. This fratricidal conflict erupted alongside the ongoing war against the Sunni insurgency, itself a deadly but conditional collaboration between Abu al-Zarqawi’s international jihadi brigades and the tribes of Anbar. It is maybe ironic that Makiya – later known and even ridiculed for his dream of a democratic, pluralistic Iraq at peace with itself – actually predicted this civil and political meltdown in 1991.

Cruelty and Silence was a bleak book steeped in Iraq’s confessional and ethnic dysfunction following decades of Arab nationalist revolution, tyranny and war. But, for Makiya, the Intifada that it described also represented a watershed moment in the history of Iraq, one that provided hope for life after Saddam. Of course, it wasn’t quite that simple. To begin with, the revolt against the regime had two fronts, and the most organised groups were also the most prominent. The Kurdish parties and peshmerga led the rebellion in the north, while Iraqi Shia militias in the south found little resistance from the regular Iraqi army, which rapidly disintegrated. The revenge of the regime was intense – and sectarian. By 1991, Ba’athism in Iraq had degenerated into the rule of a tight clique around Saddam made up of old party comrades and purge survivors, Tikriti tribesmen and the dictator’s extended family. During the Intifada, large numbers of Iraqi Sunni, terrified by the Shia revenge killings in Southern cities and the lynching of Ba’ath party officials, rallied behind Saddam and his destruction of the rebellion. “The soldiers deployed”, reported Makiya,

appear to have been selected from the Sunni towns of Hit, Mosul, Shirkat, Beigi, and from the Yazeedi community, a tiny sect based in Northern Iraq which has a history of conflict with Shia Muslims…The slogan painted on the tanks of the Republican Guard, “No more Shia after today,” was clearly not a local initiative; it was official policy. (41)

In the midst of this counterattack, special units burned precious books and manuscripts and incinerated libraries, religious schools and seminaries in Shia towns, as Saddam made good on his promise to target the very roots of Shia identity. Regime newspapers described the Shia as being “anti-Iraqi” and inflated Iran’s role in the uprising. Makiya recorded eyewitness accounts of advancing Badr Corps units – SCIRI’s paramilitary wing, the army of the House of Hakim – burning bars and casinos and decorating southern towns and cities with posters of Khomeini and Ali Khamanie. The regime convinced its supporters – and possibly even believed – that the combined forces of Badr, the old Shia party Dawa and the Iranian Revolutionary Guards were pouring over the Iranian border to lead the revolt.

In fact the Iranians expected a rout and did not encourage their Iraqi assets to waste their lives. The battle of Karbala ended with Republican Guard soldiers executing doctors and nurses and throwing patients out of hospital windows, shelling the Imam Hussein Holy Shrine and arresting and executing any Shia male over the age of 15 who crossed their path. With no discrimination, helicopter gunships strafed anyone trying to escape the besieged city. Over a decade later, Patrick Cockburn recorded a conversation with a Shia dissident from Basra who claimed that SCIRI and Badr Corps

played no part in igniting the uprising, which was a spontaneous reaction to the army’s defeat in Kuwait and the reckless and foolhardy actions of Saddam. Mohammed Baqir al-Hakim and his people, supported by Badr, were supposed to come through Mehran to Kut, but they never came. This was one of the reasons for the hostility later between the Sadrists and al-Hakim. (42)

Shia rivals still accuse Badr and SCIRI leaders of speaking Farsi among themselves and maintaining families back in Iran – a detail later picked up by Makiya in his depiction of Abu Haider in The Rope. They are considered “external” agents who betrayed the Intifada, standing aside as their fellow Shia were slaughtered. They were rumoured to have been the most enthusiastic and brutal torturers of Iraqi captives during the Iran-Iraq War.

As Makiya feared, the uprising left nothing but a legacy of conflict everywhere in Iraq – even Kurdistan, where partisans of the KDP and PUK fought a battle for power that threatened the very existence of their hard-won autonomous region. This was inevitable in the polity forged by Saddam where the assault on pluralism in the name of Arab unity had the effect of intensifying ethnic and confessional identities. “What will happen tomorrow in Iraq?” asked Makiya in 1993,

Kurdish nationalism is stronger and more aggressive today than at any time in the past, fueled by a growing realisation of what an Arab state did to the Kurdish people…Sunni-Shi’i hatred is today the most virulent potential sources of new violence. These forces are Saddam Hussein’s legacy to all Iraqis. (43)

The central theme of The Rope had been foreshadowed over a decade earlier in Cruelty and Silence: “If Iraq dissolves into even more chaos and bloodshed in the post-Saddam era, it will be principally because Shi’i political leadership failed to rise to the historic occasion and to the responsibilities which its own numbers imposed on it” (44). By 2016, Makiya’s verdict was in: the Shia leadership had failed.

The defining event was the murder of Abdul Majid al-Khoei by supporters of Muqtada al-Sadr on April 10, 2003, the day after the fall of Baghdad. As with Sadr’s conflict with the House of Hakim, the murder of al-Khoei was the result of family rivalry: a fight for supremacy in the Holy city of Najaf. Aside from the personal animosities, tactical and doctrinal disagreements divided the houses of Sadr, Hakim and al-Khoie, as well as a deep antipathy between those who had left Iraq to escape Saddam and those who remained and suffered. Abdul Majid al-Khoei had been a well-connected exile in London and America, a friend of Makiya and Cockburn, with allies in the U.S. and European governments. This was only one reason for his eventual demise in Najaf, but in some ways it was enough. In The Rope, Makiya’s narrator sees al-Khoei dying in a back alley after being stabbed to death at the door of Muqtada al-Sadr’s residence and asks his Uncle, a Sadrist, who he is: “an American agent,” is the reply (45). The role of the Sadrists in the murder of al-Khoei would eventually be covered up by the political leaders of the Shia in Baghdad, the group of exiles who went from the Governing Council to running Iraq and who saw the Sadrists as key to securing their own power. These were men, according to Makiya, who sacrificed Iraq to sectarian war in order to secure their own futures, and the cover-up of al-Khoei’s murder was a key part of this. In an interview with Dexter Filkins in 2007, Makiya recalled the new attitude among his fellow Shia exiles, including, to his dismay, the man he believed had “broken the mould of Arab politicians,” Ahmed Chalabi: “There was this attitude: “This is a war, this is it — the showdown — why don’t we just gird ourselves for it, why not recognise it as a war and fight it to win? Because we can win” (46).

It was this background that would inform his later, only very lightly fictionalised, account of Shia machinations on the Governing Council:

He was in a room with them one day when a secular Sunni Arab Council member from London, a close personal friend of his Shia Council members, also from London – they all went to the same clubs – realised his Shia friends were up to something. Following a succession of speeches made by members of the House of the Shia to cover up how they had secretly decided to vote, it suddenly dawned on this Sunni council member that a hidden agenda was being advanced under his nose, and by his London Shia pals. His face turned ashen in utter disbelief. In the deathly silence that filled the normally noisy room, sectarian politics was born. (47)

For Makiya, the disintegration of Iraq happened because the politics of sectarianism was adopted by the new rulers of Iraq, not just grassroots militias or foreign terrorist gangs. With sectarian division baked into the political structures designed by the Americans, the Shia politicians, as the majority identity in Iraq, inherited responsibility for the country’s future. When they chose to cover up the murder of somebody as significant as al-Khoie — their old friend from years of exile and opposition to Saddam — they chose to compromise their own victory. The first Shia democracy in the Arab and Muslim world began with a “big lie” at its heart, and this was not just a detail, it was a deliberate choice that would determine how the country would be governed. Makiya’s novel was an indictment of this choice and those who made it, “the men who created the politics that gave rise to all the killing, all friends of mine,” (48) who came to see Sadr and his Mahdi Army as “the shock troops in the Armageddon against Sunni Arabs that was being prophesied” (49). “The cover up,” Makiya would conclude, “lies at the core of the Shia elite’s failure after 2003” (50).

There were different poisons entering the bloodstream of Iraqi society: the poison of Najaf between the three clerical houses of the Shia and the poison of Sunni resentment at their loss of authority. The second poison found its voice in Fallujah and the other iconic cities of the Sunni insurgency that had attacked the American occupation with such fury, before turning its attention to the Shia. The Shia instruments of restitution and revenge were twofold: de-Ba’athification, which became a tool for sectarian vengeance, and the Ministry of the Interior which was occupied by Shia militias that became death squads, roaming Baghdad at night and leaving the corpses of their enemies lying in the streets or washing up on the banks of the Tigris to be discovered in the morning. While the Sunni jihadis gained international notoriety for their blades and beheadings, Shia killers also had their own grisly signatures. In The Rope, the narrator’s best friend Haider leaves Najaf to become a notorious Shia militiaman in Baghdad, renowned and feared for his inventive brutality:

His name popped up whenever a new pile of Sunni corpses was found with holes drilled into their hands and feet, and especially when the coup de grace took the form of a hole drilled all the way through the victim’s skull. Rumour said that the electric drill was Haider’s trademark. Sunni killers preferred the knife – the Prophet’s Companions used knives, they said – beheading their foes, not crucifying them. The Sunni knife was pitted against the Shia drill all through the battle for Baghdad. (51)

This was not a fictional embellishment on Makiya’s part. Anybody could see Sunni handiwork for themselves: they posted videos of their ritual beheadings on the internet. Shia violence was told in stories and rumours: Patrick Cockburn, a useful source for Makiya, described the work of Mahdi Army leader Abu Rusil, who “would leave a note on the bodies of dead Sunni saying ‘best regards’”:

‘There is no innocent Sunni,’ he said, claiming that his brother had been shot dead at a Sunni checkpoint. Abu Rusil’s victims are found with drill holes in their bodies, their bones smashed by being pounded with gas canisters, and their hands and feet pierced with nails. Once a poor man, the death squad leader preyed on his victims, confiscating their goods. He now has a house and three sport-utility vehicles, and consequently an incentive for the killing to go on. It would only end, Abu Rusil said, when every Sunni had left the country and Muqtada al-Sadr was the ruler of Iraq. (52)

Sometime in 2006, Meghan O’Sullivan, the Deputy National Security Adviser for Iraq and Afghanistan, who shared the same hopes for Iraq as Makiya, had a frank conversation with Bush: “Baghdad is hell, Mr. President,” she told him, bluntly. In the sweltering nights, pitch black because there was no electricity, murder and kidnapping and sectarian conflict raged. In the city, there was a deadly plurality of groups whose enemy was pluralism and who sought, by means of violence, purity. When The Rope’s narrator attempts a taxonomy of all the armed groups in Iraq at the request of his Sadrist uncle he is defeated by the task: “This list is incomplete. There are other groups about which I know nothing, not even their names” (53). His uncle reads the final report in despair. Even the arch-sectarian – the man who gloried in the murder of al-Khoie in the alley outside al-Sadr’s residence – recognises the significance of Iraq’s descent into militia rule, each loyal to its own sect, its own rulers and ideologies:

Iraq is just a name, son, no longer even an idea, much less a nation. A name…one more to add to the two hundred sixty-eight other names you have just given me. Would that I could say otherwise, but I cannot; I would be wrong. Perhaps its fragility is why it never ceased to require the presence of a strongman to arbitrate between its different factions. But now even the name is fast disappearing. Notice not one of the organisations on your list confers allegiance to something called Iraq. That was never the case in the past. (54)

V: All Of Us Who Leapt Into the Future With Our Eyes Shut

“And Iraq?”

“It has turned into a question for itself.”

So what did Kanan Makiya expect? What did he want?

Democracy, of course, was important — particularly because, as Makiya saw it, the usual solutions to Saddam offered up by the CIA or the State Department Arabists or the merchants of realism in Europe or other interested parties in the region tried to elide democracy altogether in the name of an authoritarian remedy that they could manage. But also key — again, as Makiya saw it — was Iraq’s historic destiny as a pluralist nation: a counter example to the pan-Arab nightmare made by the Ba’ath parties of Iraq and Syria, or to Lebanon’s sectarian carnival of death. Finally, he wanted to preserve Iraq itself – or to help the nation to redefine itself, to forge a new Iraqi identity.

As everything unravelled, the fundamental question emerged: what was Iraq? “Under Saddam, the overwhelming majority of people had been brutalized, and this brutalization had led to a very deep atomization of society – of the destruction of Iraqi identity,” Makiya explained to Dexter Filkins in 2007. “And so I asked myself: how can I find hope in this darkness? Upon what do you hang a new Iraqi sense of identity?” (55) His answer was a mutual recognition of suffering by Iraqis from every part of Iraqi society, and his practical contribution was the Iraq Memory Foundation: an archive of suffering assembled from Ba’ath party records and video interviews with victims of the regime. He hoped this would play its part in a truth and reconciliation process modeled on post-apartheid South Africa. He planned to build a museum for it on the site of the Victory Arch. But, as early as 1993, he had also spotted a problem with this:

The fact that Iraqis are already competing with each other over who has suffered the most is a sign that whether or not Saddam is still around in person, what he represented lives on inside Iraqi hearts. Herein lies the greatest danger of all for the country’s future. (56)

It was this legacy of victimisation – combined with the lure of power – that drove the decisions made by the Shia on the Governing Council to embrace, rather than transcend, their sectarian identity at the expense of Iraq itself:

In the end, they couldn’t think of themselves as Iraqis. They didn’t realise the greater prize, the whole country, is far more important than the prize of just competing with Sunnis or Kurds over who gets the most out of the pie that they now inherit. They kept on thinking of themselves in that small-minded way. Therein lies a large portion of [The Rope]. I deal with these ideas: how men internalise their victimhood, how they are unable to rise to the occasion of governance. (57)

More than the Sunni insurgency – which had its seeds in an underground network of safe houses and arms caches prepared by the Fedayeen Saddam and the Ba’ath Party militia – the breakdown of Iraqi politics along sectarian lines and the resulting civil war was Saddam’s most effective revenge on those who deposed him:

the competition over victimhood – ‘we suffered, you suffered, I suffered, I suffered more than you so I should get more’ – is a natural outgrowth of Saddam’s tyranny. The politics of victimhood is one of the diseases that tyrannies leave behind within terrorised populations. (58)

“My past,” explains Makiya’s narrator in The Rope, “the past of all of us who leapt into the future with our eyes shut in 2003, is the rule of the Great Tyrant” (59). And this past determined the future: the leap into the future was a leap into the dark.

One of the tragic ironies of post-Saddam Iraq is that the political system that the Americans helped the Iraqis to build actually embedded sectarianism within the new institutions of state. The makeup of the first Iraqi Governing Council established this error: the apportion of seats along sectarian and ethnic lines set the pattern for competition rather than collaboration, as Makiya illustrated in The Rope. The American attempt to manage plurality and balance interests, made in good faith, ended up creating a state structure that simply exacerbated conflict. (Some Iraqis concluded that this had been the plan all along.) As Emma Sky noted in her memoir, “the focus on subnational identities was at the expense of building an inclusive Iraqi identity,” an oversight that led directly to the unravelling of that very identity (60). Makiya would make a similar point at the end of The Rope, accusing the Americans of “promoting and instituting sectarianism into the body politic” (61).

The institutions of state would eventually become weapons wielded by sectarian actors – in this case, the triumphant Shia. The practical consequences of this were stark. Ahmed Chalabi, for example, took control of De-Ba’athification and converted it into a naked tool for sectarian revenge, ensuring that the Shia reckoning with the past would be violent. The Sadrists took over the Ministries of Transport and Health, which meant they could control who flew in and out of Baghdad International Airport and hospitals became sectarian killing grounds. The Interior Ministry and National Police were infiltrated by Shia militias and so became, effectively, a force of sectarian death squads, engaged in extra-judicial executions, running private prisons and kidnapping Sunni targets. Iraq’s very diversity worked against it: as Makiya had feared, nobody was willing to speak for the country as a whole or across confessional and ethnic lines. Identity politics triumphed at the expense of pluralism.

The rich fabric of Iraq’s most diverse cities was ripped apart again. By 2006, Baghdad was being partitioned along sectarian lines, with entire neighbourhoods cleansed of Sunni and Shia, leaving a patchwork of purified confessional cantons at war with each other. In Kirkuk, the outcome of ‘Arabisation’ under Saddam was reversed by Kurds who expelled Arabs from their homes and began a process of ‘Kurdification’. This kind of ambitious demographic engineering was also adopted by the Iranian-backed Shia militias who took advantage of a key turning point in recent Iraqi history: the rise of ISIS, which temporarily threatened the existence of Iraq’s borders. Led by Iran, Shia militias were organised into a broad front – the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF) – which eventually helped to defeat and clear ISIS out of northern Iraq. But then they never left: the militias, mostly from southern and central Iraq, now proceeded to seize property, agricultural land and oil fields in Mosul and the rest of Ninewa province, effectively displacing former Sunni occupants and Christian residents who had fled ISIS genocide. The PMF temporarily symbolised the deep overlap between state institutions and Shia militias whose loyalty to the idea of Iraq was, in some cases, highly dubious. But it also exposed another fault-line that now overshadows Iraqi politics: intra-Shia rivalries and feuds. The backbone of the PMF was the Badr Corps and other Iranian-aligned militias, but it also contained units loyal to Ayatollah Sistani and Sadr: its decline in late 2021 degenerated into a fight between these factions, with the Sadrists in the ascendancy. This is now, in August 2022, reaching a climax, as Sadr and his street gangs hold the entire Iraqi political process hostage.

So Makiya’s idea of – or hope for – a democratic Iraq collapsed as these conflicts emerged and raged. His dream of democracy was destroyed by the death of pluralism in Iraq. Early on, he understood that peaceful coexistence could only be achieved on the basis of mutual agreement on basic values, or a shared idea. Ultimately, this had to be the idea that Iraq was a coherent state in which majorities and minorities shared a common destiny. Not a commonality based on ideological unity, but forged by plurality. Makiya was not a political philosopher who sought to define a new theory of pluralism in his writing. He was influenced most closely by Arendt in his defining work, Republic of Fear, but did not attempt grand theories like she did in The Origins of Totalitarianism. Instead, he studied her work and found in Ba’athist Iraq something close to her totalitarian idea: an architecture of fear and a political aesthetic; an intricately designed network of para-state party organisations, secret services and systems of torture and surveillance; a programme of ethnic and sectarian genocide pursued in the name of an expansive, apocalyptic ideology.

Makiya’s own vision of post-Saddam Iraq was something else again: a confluence of influences, allegiances, vague tendencies and — more importantly, and a running theme until the bitter end — hopes for what could come after. This was encouraged by his own experience and studies of what Iraq had once been and had offered the world before the pan-Arabists imposed their own dreams on the country. Undoubtedly he had also been influenced by his adopted countries during exile – Britain’s parliamentary democracy, of course, but mostly America, which had built a system based on pluralism by writing a constitution for the states that chose to unite after a revolutionary war. The constitution written for Iraq after Saddam – by Iraqis but overseen by the U.S. – did not achieve this balance: it was either too soon or too late; it was certainly flawed, and encouraged the sectarianism he had hoped it would destroy. Dialogue died, and violence and dreams of power replaced it. Despite his own hopes, Makiya had himself recorded and explained the reasons why this would happen from his earliest writing on Iraq. But even at the end, at the final moment of despair, he would not concede its inevitability:

Civil war and a complete breakdown in Sunni-Shia relations were not inevitable consequences of war and occupation; Iraqi leaders knowingly or unknowingly willed them into existence. Individuals with weight, who would not cater to the basest sentiments, might have made a difference. (62)

They never did; to this day, they still haven’t. For Makiya, this was, in some ways, the most bitter lesson of all.

- Quoted in Lawrence Weschler, ‘Architects Amid the Ruins’, New Yorker magazine, January 1992

- Kanan Makiya, The Rope (Pantheon Books, 2016), p.303

- Ali Allawi, The Occupation of Iraq: Winning the War, Losing the Peace (Yale University Press, 2008), p.72

- George Packer, The Assassin’s Gate: America in Iraq (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2005), p74

- Quoted in Packer, p.179

- Alan Johnson, ‘Putting Cruelty First: An Interview with Kanan Makiya (Part 2)’, Dissent magazine, 2006: https://www.dissentmagazine.org/democratiya_article/putting-cruelty-first-an-interview-with-kanan-makiya-part-2

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Kanan Makiya, Cruelty and Silence: War, Tyranny, Uprising and the Arab World (Penguin, 1994), see Section 2, ‘Silence’.

- Ibid., p.80

- Ibid.

- Kanan Makiya, Republic of Fear: The Politics of Modern Iraq (University of California Press, 1998), p.149

- Tamara Chalabi, Late for Tea at the Deer Palace: The Lost Dreams of My Iraqi Family (HarperPress, 2011), p.157

- Bassam Tibi, Arab Nationalism: Between Islam and the Nation State (Palgrave Macmillan, 1997, 3rd Ed.), p.118

- Quoted in Johnson, 2006

- Republic of Fear, p.163

- Ibid., p.256

- Cruelty and Silence, p.219

- Republic of Fear, p.257

- Quoted in Republic of Fear, p.20

- Quoted in Weschler, 1992

- Kanan Makiya, Post-Islamic Classicism: A Visual Essay on the Architecture of Mohamed Makiya (Saqi Books, 1990), p.18

- Guy Mannes-Abbott, ‘Mohamed Makiya: Deeply Baghdadi’, Bidoun: https://www.bidoun.org/articles/mohamed-makiya

- Chalabi, p.166

- Kanan Makiya, The Monument: Art and Vulgarity in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq (I.B.Taurus, 2003), p.79

- Ibid., p.82

- Ibid., p.20

- Ibid., p.22

- Ibid, p.62

- Ibid., p.66

- Ibid., p.113

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Kanan Makiya, ‘What is Totalitarian Art?: Cultural Kitsch from Stalin to Saddam’, Foreign Affairs, Vol 90, No.3, May/June 2011

- Republic of Fear, p.204

- Ibid., p.69

- Ibid., p.141

- Cruelty and Silence, p.219

- The Rope, p.198

- Ibid., p305

- Cruelty and Silence, p.97

- Patrick Cockburn, Muqtada al-Sadr and the Battle for the Future of Iraq (Scribner, 2008), p.68

- Cruelty and Silence, p.212

- Ibid., p.226

- The Rope, p.31

- Quoted in Dexter Filkins, ‘Regrets Only?’, New York Times, October 7, 2007

- The Rope, p.91

- Ibid., p.301

- Ibid., p.303

- Ibid., p.308

- Ibid., p.187

- Cockburn, p.186

- The Rope, p.202

- Ibid., p.206

- Quoted in Filkins, 2007

- Cruelty and Silence, p.219

- Quoted in Lawrence Weschler, ‘We didn’t have politicians up to the task: A conversation with Kanan Makiya’, Public Books, November 2016

- Quoted in Johnson, 2006

- The Rope, p.185

- Emma Sky, The Unravelling: High Hopes and Missed Opportunities in Iraq (Atlantic, 2015), p.60

- The Rope, p.317

- Ibid., p.316