About a week ago there was a reunion at Harvard of some of the people who were involved in occupying the administration building there, and in organizing the strike that followed that in 1969. It was the kind of event where the first thing people told each other was how they’d hadn’t been sure about coming to the event. Some of that was because being involved with anything that has the Harvard name on it sounds, well, actually is, self-aggrandizing. (Or as my therapist said in pre-school after my tentative divorce from my mother, ‘even being angry at something is still a way to stay connected to it, isn’t it, Jay?’) Also, people feared a reprise of the hard feelings – feelings along the lines of murderous contempt – between those who had been aligned with the Progressive Labor Party and those from what was then called the New Left. I won’t repeat those arguments here because gosh, neither side had exactly seen what the working class or the youth of America wanted, or anyway could be made to want, and it all seems kind of Big End versus Little End now, and wasn’t one a fool ever to care?

Still, as people rose to talk about their lives over the past fifty years something about our gray-haired frailty overcame our hesitations about being there. Almost all talked of how their work organizing against the Vietnam War and for the strike had inspired them, like a friend of mine from college who spoke about the efforts he and his co-workers had made for El Salvador. When he had first told me about that, many years before, I’d probably thought well, that will come to nothing, as that’s what I usually think, and then at the reunion, he said that it had come to nothing, though some people from El Salvador had told them that the concern his group had shown had buoyed their spirits. He cried a little as he spoke about the efforts he and his co-workers had made for El Salvador, and I thought that he was the one who was wrong now, that it was amazing that anybody ever in the history of the world didn’t just – as I did – wake-up reluctantly, eventually get out of bed, make coffee, read the paper, and have opinions, and instead did something that buoyed some one’s spirits, like fighting for justice in El Salvador, or working against the death penalty, or helping to slow the destruction of the planet by fossil fuels, even when all of them know it will mostly come to nothing.

Me, I’m not that person, but I had once been active as a poster-maker during the strike, and so I was asked to speak at a reception for a display of the posters at the Pusey Library, which is named for the same President of Harvard who, when watching the demonstration, had reportedly said to another administrator, “Don’t you think the devil is in these people?” He had ordered the cops to clear out the demonstrators, which they had done with particular brutality, as was appropriate in punishing demons, or at least spoiled Harvard kids. This evening at the Library, the Dean of the Kennedy School – a place which we generally had thought of then as a nest of rogues and imperialists – made a self-congratulatory speech to us about how the strike had led to something good for Harvard, though I don’t remember what exactly as by then I had overdosed on irony and didn’t know who I was anymore, though probably that feeling and its causes will soon matter about as much as the fight over which end of the boiled egg one should break.

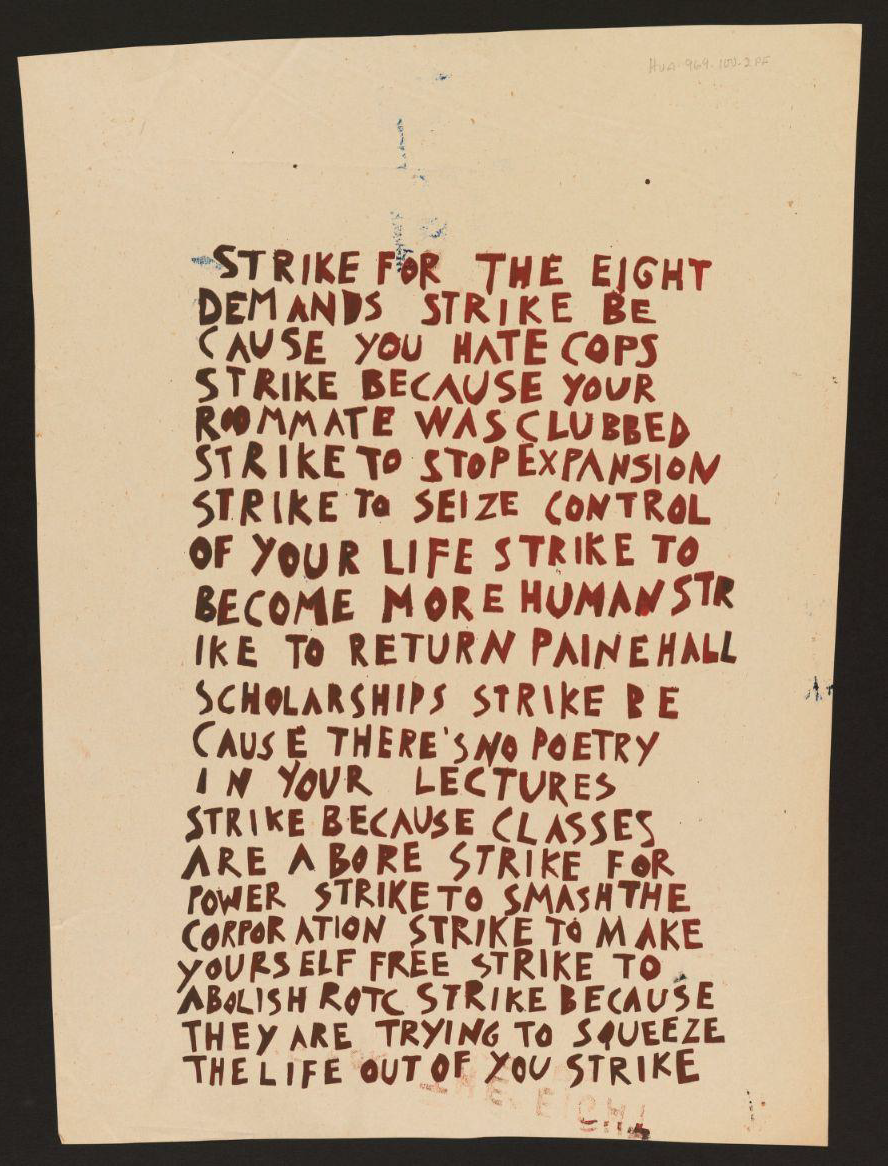

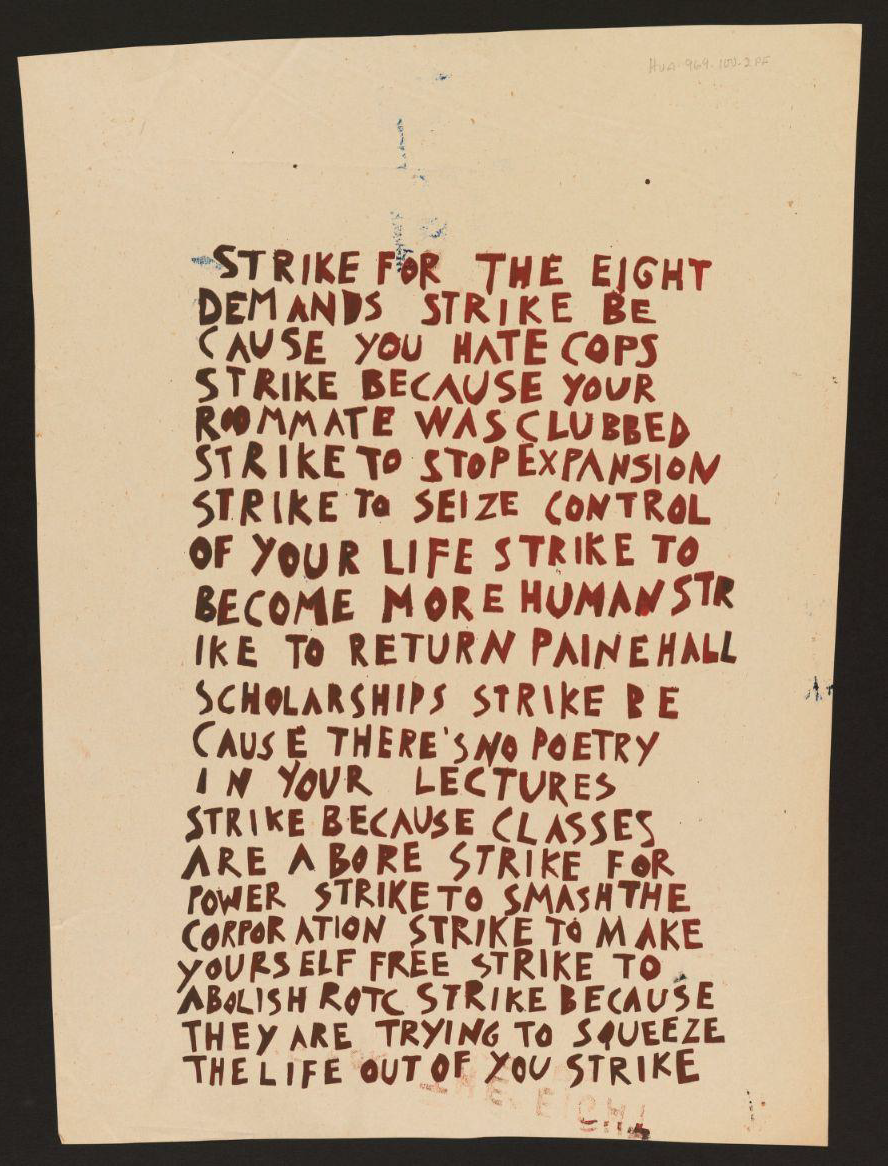

Anyway, here is a poster of mine from that time:

And here is what I said about it:

The poster came about because when many of you took over the building I was already on probation from the Payne Hall demonstration, and I was afraid to stay with you because I thought I’d be expelled and I wasn’t ready for the consequences of that. More than a few of you were in that exact situation and went in to the building anyway, so that next morning I could add my not being in the building when the cops came to my guilt. Guilt was my prevalent feeling, mood, my daily meal in those days – mostly guilt about the war and what we were doing in Vietnam, so that last bit was a small drop in the bucket.

Then after the bust, and the response of our fellow students – I felt different, energized, exhilarated even; there were others and something to be done with others; there was the strike. My friend at the time, Karen Tillinghast, had a silk screen and that seemed to me about as amazing as having a printing press of your own. I scribbled a poster that interspersed the then six demands of the strike with a few other things, like strike because there’s no poetry in your lectures, or strike because they’re trying to squeeze the life out of you, and yes, that was meant to be a little self-mocking and silly but not just. It came out of that exhilaration I mentioned – the feeling that this was about Vietnam, and the depredations of Harvard in the working class communities, but also about us and some probably romantic idea of what a more vivid, and more comradely life could be if one were part of a community that was working to establish itself so it could work for itself and for others.

Anyway, Karen cut the anti-looking letters and we silkscreened in my kitchen – I think Josh Freeman was part of that, and Mike Prokosch, among others. Then we heard that lots of poster-makers had set up shop in the big hall at the Graduate School of Design and we went there, and joined them, and lots more people came there later. There were many mixed excited voices in the great hall, and a lot of rolls of newsprint, and paper-cutters, and paint-stained clothes, and paint-stained floors and paint-stained walls, and it all felt like my new beloved messy community, meaning a lot of people who felt the same exhilaration I did, that same lifting of guilt in the activity of pulling the brush across the screen. I think if you look at the words and pictures displayed here you can feel that excitement – that sense of people coming together to invent a community that could fight for itself and for others.

I know from listening to some of you today, and from following your lives and work before, that many carried that feeling forward and remade it in your lives through your work for yourself and others. Me, I became a teacher – well, no, but I have that title anyway – and yes I try to include some poetry when I lecture on Marx or whatever, and I also think sometimes, hey what if one of the students said, “are you trying to squeeze the life out of us?” And I’d have to say, maybe not intentionally, but yes, I bet I am helping to do that, and I’m sorry, but really you should get together with others the way we did and at least try to stop me and build something better for yourselves.

xxx

After that talk we had drinks and ate crudités and canapes – which phrase could serve as an ironic way to end this piece, except that I now knew that most of the people there were, unlike me, were not only going back to their work as lawyers, teachers and nurses and administrators, but also to mostly unironic meetings for demonstrations to ban nuclear weapons, or stop pipelines from disfiguring the landscape, or to force their college to divest from fossil-fuel stocks, and they certainly knew from experience that it might all come to nothing but more meetings, more phone chains and mailing-lists, more demonstrations, more attempts, more failures, but maybe it would provide some encouragement for others that who knows, might someday have a different result, and maybe for the demonstrators, now a diminishment in the guilt and despair of graduates of elite colleges in a world that they knew very well indeed was canape-providing for some people and horribly brutal for most of the rest.