Manhattan’s Just Above Midtown (JAM) gallery became a haven for Black Atlantic artists in the 70s and 80s. A current exhibit at MOMA chronicles work first shown at JAM and includes art by Lorraine O’Grady. The author of the following post was born long after JAM’s moment. He encountered O’Grady’s work on the campus of the University of Chicago. It launched him on a trip that took him back to the playful start of his own art-life…

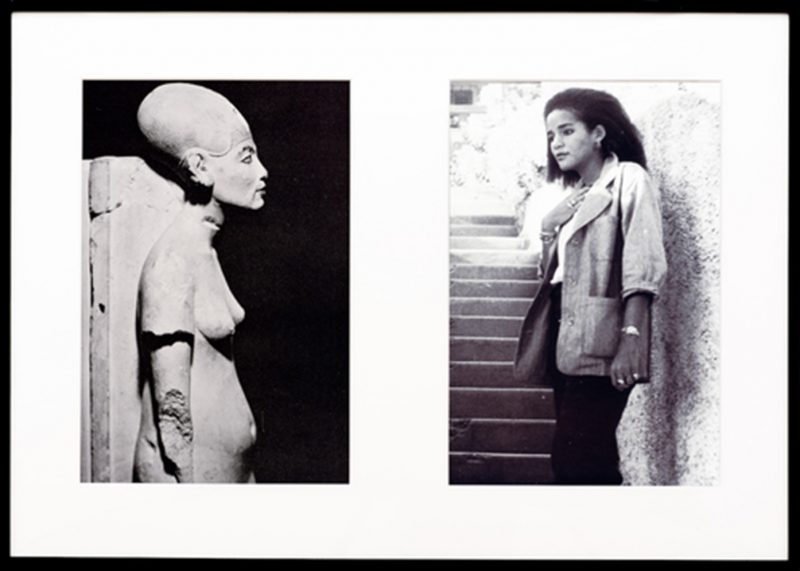

I came across one of the sixteen diptychs that make up Lorraine O’Grady’s Miscegenated Family Album—(Cross Generational) L: Nefertiti, the last image; R: Devonia\’s youngest Daughter, Kimberley—in the the Booth collection.

It’s placed in an international corner with pieces from Pakistan, Australian fishing nets, German photographer Ursula Schulz-Dornberg’s pictures of the Soviet steppe, and another photography project from China. Maybe this area works like the rest of Booth’s eclectic mixes, but it made me feel like I was at a pricey international art auction, a realm where diversity training and pseudo-artistry converge. The Scottish accent on the audio guide—an ocean away from South Side’s—sounded like a Sotheby auctioneer’s. I was grasping for a means to connect with this less than accessible part of the collection, until I found O’Grady’s work. Initially drawn in by its title. I wondered if the piece might have some personal resonance, since I’m mixed. My way into the work, though, would rest on my little history at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as well as my biracial identity…

The Met on a rainy day is a fine thing. It was the first time I had been in a while (this was after the first Covid wave). Under the enveloping awning to keep dry from the summer rain (even though it didn’t really need escaping from), I got ready to show my vax card at the door—a procedure that still felt new and strange at the time. The usual harmonies from different languages were muffled by masks and the decrease in tourists. Despite these changes, it was good to be back…until it wasn’t. It was quick, slight. I was checking my bag, and one of the attendants—my memory fails me here—was it a hand gesture, a contemptuous tone, a directive, a condescending combo? My reaction, though, remains easy to recall. I felt disrespected. The attendant had somehow made it clear he assumed I didn’t know where I was supposed to go.

Maybe I misunderstood. My memory might be playing tricks on me, mixing my Met come-back with a different visit where an acquaintance—sure they were the Met savant—dragged me to the worst parts of the collection—storage rooms in the American wing—and dissed my favorite Italian Maiolica ceramics exhibit. (I promise it’s really cool!) Perhaps I had a chip on my shoulder. A ready defensiveness: how many people who looked like me were in those peering crowds? What counts, though, is my reaction hints at my identification with mine own Met.

My dad took me there a lot when I was a kid. We would get off the crosstown Four Bus a stop early, so I could get a dose of the terrific playground right across the street from the museum. “Ancient Playground,” as it was called, had a dynamic layout: complicated structures balanced by interspersed free spaces. The center was a pyramid with four ground level entrances and a tunnel up to the top. The structure was climbable from the outside, too. At the peak it connected to an aqueduct that ran above ground to a basin with a sprinkler. The playground had different levels with different styles, so it felt like you were going in between different realms as you explored. Water gun fights became tactical battles. Tag became a matter of cleverness not physical prowess. It would seem like this pre-museum fun would be a good way to get out kiddie energy before contemplative Met time, but, in my early years, the walk across the 85th St. transverse felt like the walk to another playground.

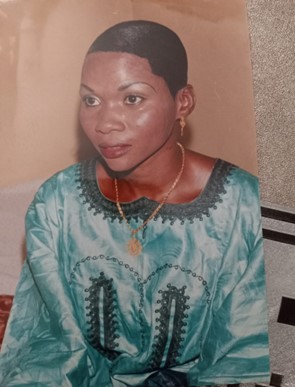

Elitist, stuffy, boring, dead, some of the adjectives many people would turn to when thinking about museums, could not describe the Met I knew—I felt it was teeming with life. The samurai mock-ups, in their dark room off the medieval aisles, scared me. (A fear that might not have been too far from what a common Japanese farmer once felt seeing that mercenary iron.) The Temple of Dendur still felt heavy with spirits of the Nile. I claimed the American wing’s mock mansion as my own fantasy home. It would take a while before European oil paintings could do anything for me. (Hokusai prints came across earlier.) The classical sections were really my access points. I was a Greek mythology (and history) kid (thanks to Rick Riordan), so Athenian amphora and Spartan helmets did not seem worlds away. I came to know Ancient Egyptian history well, too. There was no other gallery that gave such a good timeline sense of a civilization. I would start in prehistory, shards and stones, curve my way around the rooms—mummies, scrolls, impressive monuments—and up through history. I could see the art styles, iconography, and influences change, until at the end (back at the northern entrance) I would meet the Fayum portraits made for traditional sarcophagi, but clearly Greco-Roman influenced (“almost post-Renaissance” according to the Met website). There was, though, a little blip in the constructed timeline—a flash to the present: a statue of Queen Hatshepsut ca. 1479–1458 B.C. It could not have been the first time we walked past her… she didn’t really stand apart from her neighboring nondescript royals in a room off the wing’s main drag. One of those times, though, my dad realized the sedate and unadorned queen looked like my aunt Awa Diouf.

I had to take my dad’s word because I did not have a good sense of Awa. She lived in Senegal, and I had only been once when I was a toddler. I thought I could see, though, Hatshepsut’s youthful Diouf features. After finding Awa’s twin in the Met, I began to make little quiet pilgrimages to Hatshepsut. I would take the long way through the gallery just to stop by and make sure tata (auntie, in Wolof) Awa was alright. Her presence helped me feel at home in the Met.

…..

When I ran into Miscegenated Family Album, I realized Awa-and-Hatshepsut might enable me to connect with O’Grady’s art, but I wasn’t a believer immediately. What was the Album and L: Nefertiti, the last image; R: Devonia’s youngest Daughter, Kimberley all about? And who cares whether so-and-so’s niece appears to kind-of resemble an Egyptian Queen? Apart from its eeriness, there seemed to be no helpful formal analysis. What’s on offer at Booth is simply two prints with white background. Having done some research into the piece, though, I now realize the problem isn’t with the Album, but Booth’s presentation. More information about an artist would enhance most art, but, for this project, context is essential not supplemental.

Booth’s bare captions don’t spell out how the Album comes out of an earlier performance art piece from 1980, Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline.

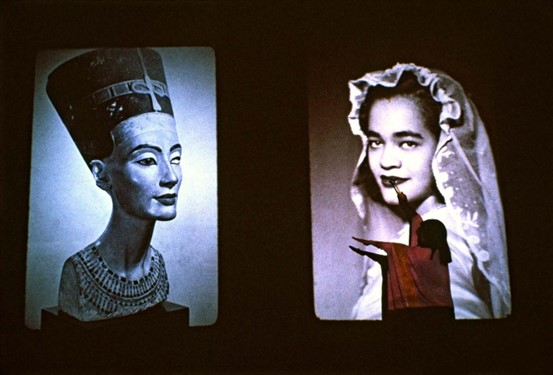

A picture of Lorraine O’Grady performing Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline.

The work was a response to the death of O’Grady’s sister Devoline and informed by a trip to Egypt. In a CAA journal article, O’Grady details her process:

My older sister, Devonia, had died just weeks after we’d got back together, following years of anger and not speaking. Two years after her unanticipated death, I was in Egypt. It was an old habit of mine, hopping boats and planes. But this escape had turned out unexpectedly. In Cairo in my twenties, I found myself surrounded for the first time by people who looked like me. This is something most people may take for granted, but it hadn’t happened to me earlier, in either Boston or Harlem. Here on the streets of Cairo, the loss of my only sibling was being confounded with the image of a larger family gained. When I returned to the States, I began painstakingly researching Ancient Egypt, especially the Amarna period of Nefertiti and Akhenaton. I had always thought Devonia looked like Nefertiti, but as I read and looked, I found narrative and visual resemblances throughout both families.[1]

O’Grady also came across the ancient Egyptian ceremony called the Opening of the Mouth, in which a priest would animate a statue of a dead person to help the transition to the afterlife (the Egyptian word for sculpture means “a thing that is caused to live”).[2] She even came to identify with Nefertiti’s younger sister, Mutnodjmet—who seemed (like O’Grady) to have had a conflicted relationship with her older sibling. All of these concepts came together on the stage at the Just Above Midtown Gallery:

The first part of the performance consisted of side-by-side projections of slides of Nefertiti and Devonia and their families, set to a soundtrack that narrated the stories of the women’s lives, one from a historical point of view, the other from the point of view of the little sister (O’Grady). The progression of slide pairings activated a flickering of resemblance and dissemblance, thanks to the often uncanny similitude between the projected faces or the noble poses and the contrast or correlation between the trajectories of the title characters’ lives… In the second part of the performance, O’Grady herself came onstage wearing a red caftan and attempted to enact the narrator’s directions for the ancient-Egyptian Opening of the Mouth ceremony… As images of the two “sisters” reappeared on the screen, O’Grady approached the projected faces and struck their mouths with an adze as the tape proclaimed, “Hail, Osiris! I have opened your mouth for you. I have opened your two eyes for you.”[3]

O’Grady would run this performance several more times until 1989. In 1994, she reconfigured sixteen of the original sixty-five diptychs for her visual (non-performative) art piece, Miscegenated Family Album.

The album is a (materially and subjectively) compacted version of the original Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline. O’Grady’s work, though, has suffered an even larger distortion as the album’s images—meant to be viewed together—have been split up into different collections. O’Grady wasn’t all that glad to have her stuff chopped and screwed: “The installation is a total experience. But whenever diptychs are shown or reproduced separately, as they often must be, it is difficult to maintain and convey the narrative, or performance, idea. As someone whom performance permitted to become a writer in space, that feels like a loss to me.”

Just a couple lines about Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline and its inspirations would help ground the work, which now drifts on Booth’s third floor. Would you slice up a smaller version of a larger complex painting, hang up one piece (without images of the whole work), eliding any reference to the first original work and its intents, and imagine you’ve done justice to the artist? In its current state, Booth’s piece of Miscegenated Family Album feels like it’s there to tick off diversity requirements. As if the curator, at least of the “international corner,” is a spiritual cousin of college admissions photographers out to cram that perfectly multi-cultural friend group into one shot (even if the subjects aren’t actually all friends). Per the plaque at Booth: “both families [Nefertiti’s and O’Grady’s], in fact, reflect the consequences of generations of cross-cultural exchange and interracial marriage.” Check mark, interracial, check mark, black, check mark, Egyptian? Am I being too cynical about Booth’s approach to this art-world? There is, after all, always something to be said for less-is-more interpretation, for fresh eyes. And academic riffs may leave you in unhelpful places. Cultural conversation about Miscegenated Family Album focuses on the social justice aspect of O’Grady’s work. Contemporary art critic Mira Dayal writes: “A desire to address the racism in scholarship on Egyptian art, and in museum practices more broadly, was surely a spark for Miscegenated Family Album.”[4] This thesis seems wrongheaded to me. The Album and Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline are meant to be cathartic not analytic. A politics of culture could be in the equation, but the emotions involved seem to have been sparked by the particulars of a painful, familial loss. While O’Grady’s work may have wider implications, I think she is encouraging us to reflect not on academia’s pet issues, but on moments in our lives when art has been a balm. Ancient Egyptian history and culture gave O’Grady a way of dealing with her pain—when have we not turned to other worlds when ours are too dark?

I’ve been reading Speak/Memory, good training for thinking about my early years. There’s a passage where Nabokov imagines his French nurse’s first Russian night:

Very lovely, very lonesome. But what am I doing in this stereoscopic dreamland? How did I get here? Somehow, the two sleighs have slipped away, leaving behind a passportless spy standing on the blue-white road in his New England snowboots and storm coat. The vibration in my ears is no longer their receding bells but only my old blood singing. All is still, spellbound, enthralled by the moon, fancy’s rear-vision mirror. The snow is real, though, and as I bend to it and scoop up a handful, sixty years crumble to glittering frost-dust between my fingers.

New England snow is the magic stuff for Nabokov. The Met’s steps’ metallic railing—roots coursing with energy, anticipatory rush at the touch—is my New England snow. It led me up the steps, to my childhood’s halls and to yet unknown sights in new galleries. It slid me down once the lights went low. The odd two-pronged guide remained unchanged and its volts, though shifting from season to season and year and year, never lost force.

…..

Lately, when I’ve been in the city and hit the museum, I’ve tended to skip the Ancient Egyptian exhibit. I suppose its mystery seemed a bit too kiddie. But I’m remembering, just now, a recent family trip to the Met. We’d gathered around the classic Christmas tree with the nativity scene. My cousin’s son Arlo was having a blast making out all the little happenings in and around the big tree. Feeling the charm was a little beneath me, I was anxious to check the Impressionists upstairs (who don’t leave me expressionless anymore). I’m shamed when I recall my attitude… I’d forgotten my playground education on the border of the Met and inside it.

I’m coming back to NYC soon. This time, thanks to Lorraine, I’ll check up on tata Awa in the northern corner of the museum, where light streams in, and not many people walk by.

……………

Notes

[1] O’Grady, Lorraine. “Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline.” Art Journal 56, no. 4 (Winter, 1997): 64-65.

[2] Dayal, Mira. “Close-Up: Theory of Relativity: Mira Dayal on Lorraine O’Grady’s Miscegenated Family Album, 1980/1994.” Artforum International 59, no. 5 (03, 2021).

[3] Mauss, Nick. “The Poem Will Resemble You.” Artforum International 47, no. 9 (05, 2009): 184-189,10.

[4] Dayal, Mira. “Close-Up: Theory of Relativity.”