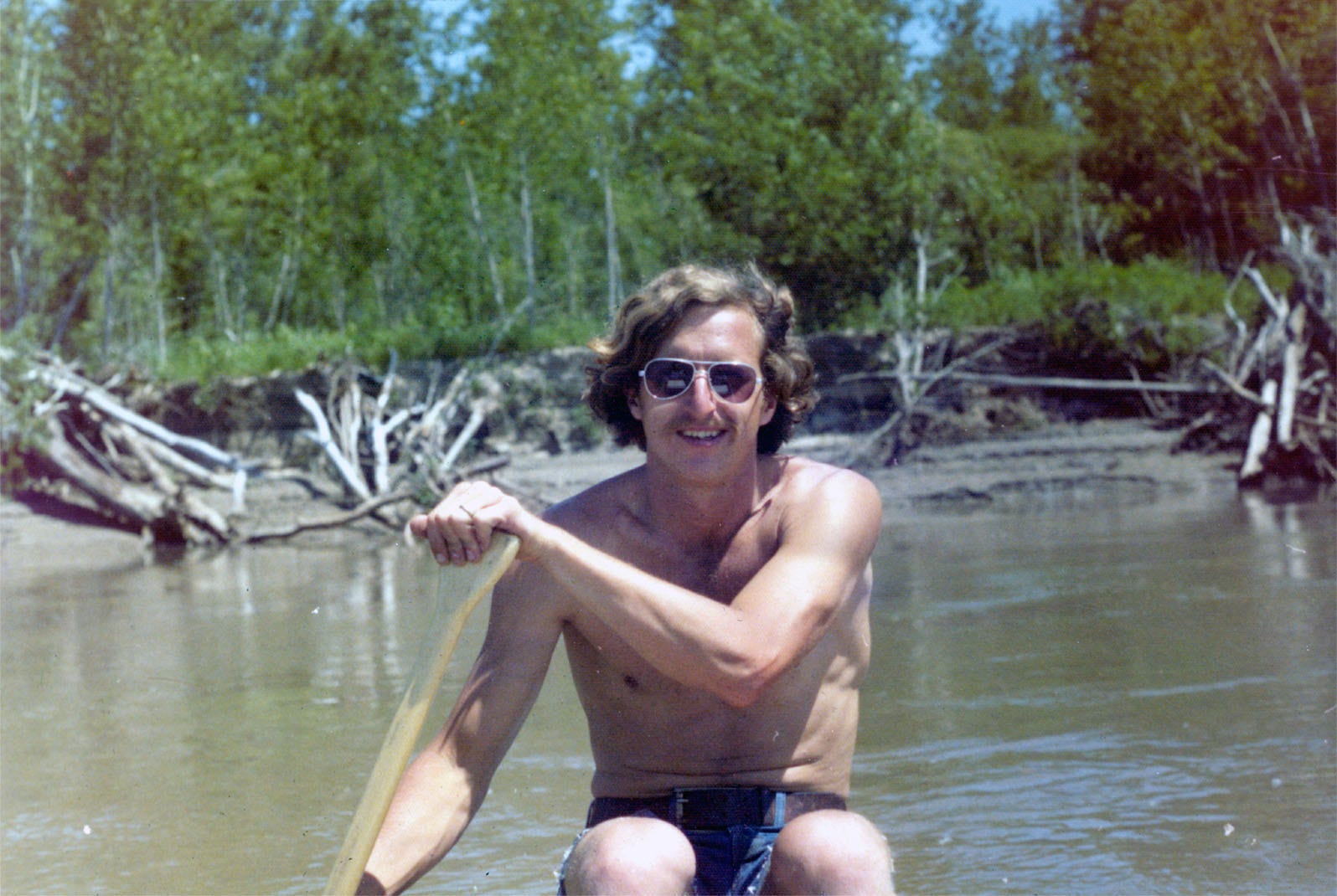

My brother Frank

If you’ve known someone who died by their own hand, you walk around for the rest of your life with a question mark so real, you can see it with your eyes and feel it on your skin. Why? What drove them to do it? Even though people commit suicide all the time, no one wants to confront that darkness or our resentment that they have left us with the terrible knowledge that death is not just a reality, it’s an option.

I’ve known several people who have taken their own lives, but the two I miss most dearly are my brother, Frank, and my friend the folksinger, Phil Ochs. They were very different people, and their suicides were very different.

Frank left his home one day in 2008 without telling anyone where he was going and shot himself with a Russian pistol behind a funeral home, as if to spare everyone the bother of having to deal with his body. He left no clues that he would ever do such a thing, but when his wife Debbie called me soon after his body had been found, she said simply, “Luc, the war finally got him.”

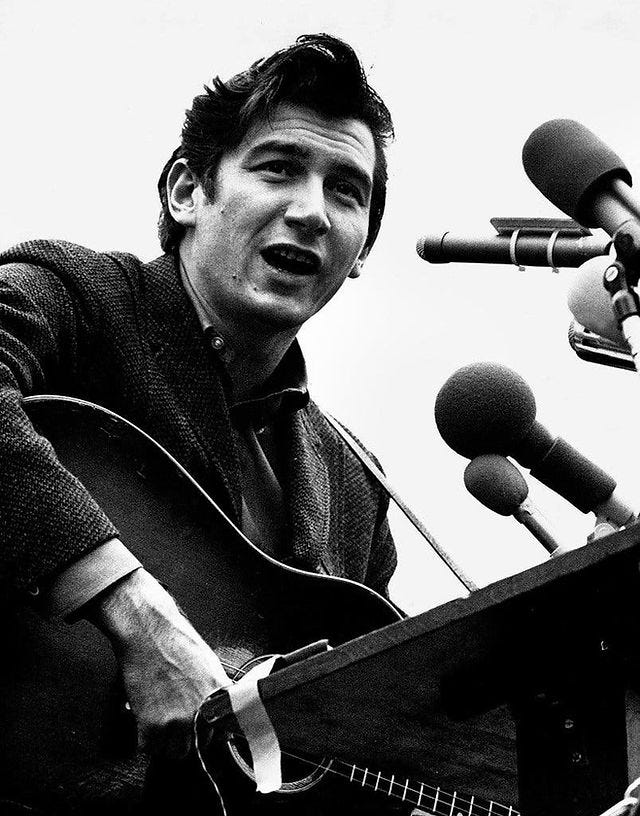

Phil hung himself in 1976 in his sister’s house after a long downhill slide into alcoholism and depression that his mind tried to stave off with mania, taking on the identity of a character, John Butler Train, whom he said had murdered Phil Ochs. He talked of suicide to family and friends, me among them.

Phil Ochs

It is one of the terrible truths of suicide that none of us will ever know the reason either Frank or Phil killed themselves. Frank never talked about ending his own life, and though Phil mentioned suicide in conversation, many took it as one of those grandiosities he was fond of, like wearing a gold lame suit made by Nudie in tribute to Elvis at his 1970 Carnegie Hall concert and during a time of anti-war protests, singing songs of conservative country stars Conway Twitty and Merle Haggard in addition to his own songs.

Frank was anything but grandiose. He was sometimes called “the quiet brother” by friends speaking of our family. But he had a temper that could be triggered by something Frank had been dealing with inside himself without telling anyone. I once saw him hit a guy in a high school hallway who was much taller and heavier than Frank. The guy said something belittling to Frank as he passed going in the other direction, and Frank snapped a left hook into the side of his head that put him out on the floor for more than a minute. Frank kept walking. No one but me saw Frank’s fist fly into the side of the guy’s head, and he never knew what happened. I had to tell him later it had been Frank that put him out, suggesting that continuing to bully him wasn’t a very good idea. He left Frank alone after that, which kind of describes the way Frank went through life. He wanted to be left alone to do his job, fish and hunt, and raise his sons and love his wife.

What got me thinking about my brother’s and Phil’s suicides was seeing a clip on X – formerly Twitter – from the Phil Ochs Memorial Concert at the Felt Forum in New York in 1976. The clip is of Tim Hardin singing one of Phil’s best songs, “Pleasures of the Harbor.”

I was at the concert that night, sitting next to Abbie Hoffman, who was, as it happened, a fugitive from justice. Tears were running down my face as Hardin sang Phil’s song, and as it ended, I looked over to see Abbie weeping, too.

Looking back from this time, the song’s lyrics seem to be a farewell from a man who knows he is leaving his world for another. As you watch the video of the song, you’ll see Tim Hardin kind of stagger away from the mic and then turn around to find it before he begins singing. He was a heroin addict at the time of the concert, and the way he sings the song is a junkie’s lament, as if he knows his friend Phil better than anyone on earth at that moment. It’s not sadness in his voice; it’s knowledge of himself he finds in Phil’s lyrics and doleful music:

‘Til the fingers draw the blinds

Sip of wine

The cigarette of doubt

The candle is blown out

The darkness is so kind

Oh, soon your

Sailing will be over

Come and take

The pleasures of the harbor”

It’s easy to make too much of the fact that four years after Tim Hardin sang this song, he was found on the floor of his Hollywood apartment, dead of an overdose. Declared “accidental” by the coroner, who will ever know? But I don’t think you can watch Hardin’s face and hear his voice singing Phil’s mournful lyrics and not see the thing that Phil’s drinking and Tim’s use of heroin attempted to avoid – the physically visible feeling that overcame Hardin as he sang the song, especially near its end.

My brother Frank was a big game guide in New Mexico when we were young, and I once went on a bear hunt with him as he guided two wealthy Texans into the wilderness east of Taos. We spent the day trying to follow the howls and yelps of his hunting dogs as they chased a bear. For a couple of days, the Texans got nothing. Then on the last day of the hunt – the day that would produce a big tip or bitter disappointment from the hunters and no tip at all – the dogs treed a bear. Frank was the first one to follow the dogs’ calls and find the tree and the bear. Later, Frank told me he called the hunters on a two-way radio and gave them directions to find the tree, and then he sat down to wait for them to arrive. After a few minutes, the dogs, exhausted from the chase, began to go to sleep on the floor of the forest beneath the tree. Finally, there was no dog left awake to bellow, and the bear began to climb down the tree.

Frank needed to keep the bear in the tree until the hunters arrived to shoot it, so he took his hatchet and cut down a sapling and sharpened one end and jabbed the bear in the butt every time he came within reach. After more than an hour of this, the hunters found the tree and one of them shot the bear, who was about 40 feet up the trunk, draped across a branch, resting like the dogs and my brother.

Describing the scene later as the hunters sat around the fire drinking very expensive whiskey, Frank said the whole thing would have been funny if it didn’t remind him so much of the way the war was fought in Vietnam. Soldiers would go into the woods and hunt for Viet Cong, and when they found them, they would trap them in an area and sit back and call in an airstrike on them. It was like shooting a bear in a tree, Frank told me. On his face was a look that told me he knew it wasn’t fair for either the hunters or the hunted.

Frank left his job as a guide not long after that. Some years later, we went back into the New Mexico wilderness where we had been on the bear hunt, fishing this time. Frank told me some more stuff about Vietnam that I won’t repeat here, and by that time, he had a look on his face that I remembered seeing on Dad’s face and Grandpa’s, a mask that could not conceal what was going on inside each of them. It was the mask brought on by the war – not the horrors of what happened, but the horror of discovering what each of them was capable of.

It seems odd to say this, but thinking about Phil and Frank, it came to me that the difference between truth and lies is feeling. A lie is easy, because it’s pulled from the air, unanchored by reality or emotion. To tell the truth is hard, because you’re willing to confront something real in the world and within yourself, and you can’t do that without feeling pain or guilt or the darkness of knowledge, or even the depth of your love for another.

It’s scary, because the ability to feel is a gift that can lift you up or send you into despair; to feel is to realize the truth about the world around you and within you, and to know what you are capable of. Some people end up killing the self where those feelings live.