In 20 years, when a new generation has its say, will gangsta rap be regarded as a latter-day version of the coon song, an old-time genre in which black bloods thug out and triumph? Will 50 Cent be removed from the MTV pantheon, and Eminem consigned to the limbo of suspect artists for his “minstrelsy”? It’s not an academic question, since many images of black people once considered positive, or at least respectful, now look profoundly bigoted. At a future moment of heightened awareness, progressive fans of rap when it trafficked in bitch-baiting may have to reconsider their passion. That’s what just happened to devotees of another pop music icon from the mid-20th Century.

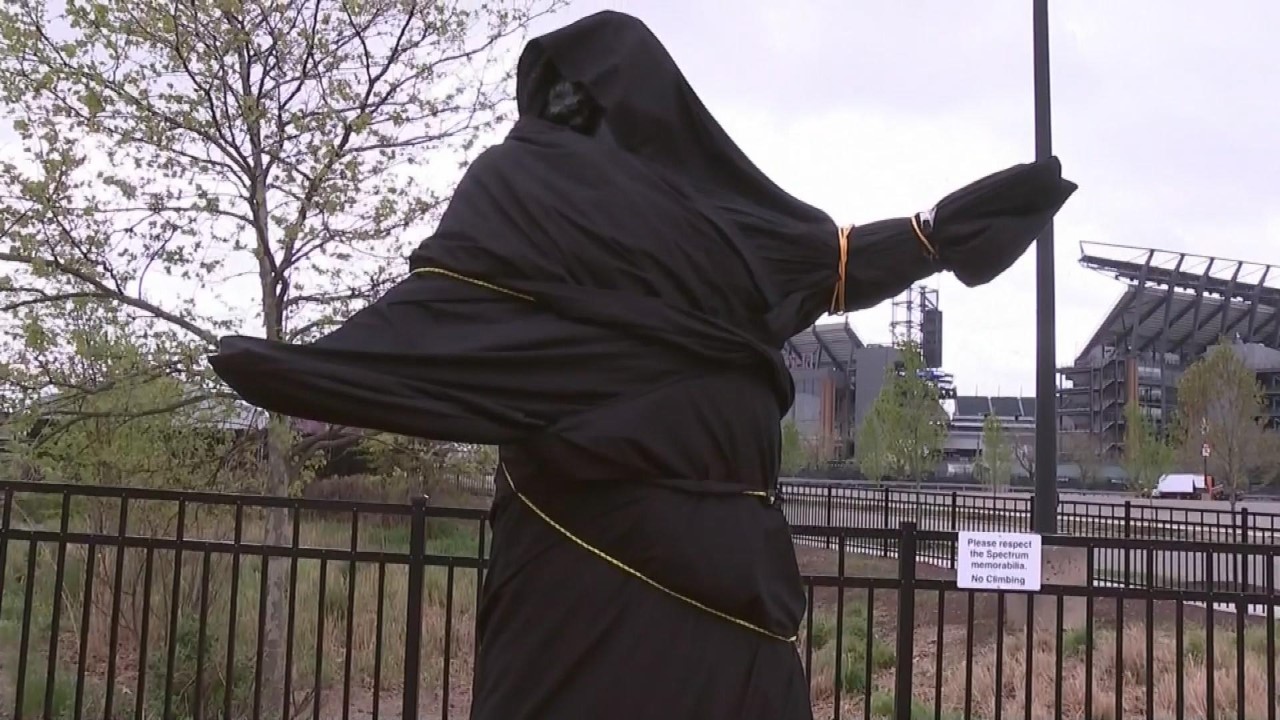

Kate Smith once merited a statue to commemorate her ties to the Philadelphia Flyers. For years, her famous rendition of “God Bless America” greeted the crowd before a game, and the custom spread to teams across the country, until history caught up with the performer once known as “the songbird of the South.” As scandal engulfed her, the Flyers had her statue wrapped in a black drape, so that it looked like a mournful work by Cristo—and then they carted it away. God bless the land of the woke.

In her lifetime, Kate Smith recorded several thousand songs, including two that sound shockingly racist today. One of them, “Pickaninny Heaven,” was part of a 1933 movie in which orphaned black children were told of a promised land where “great big watermelons roll around and get in your way” and “Old Black Joe is the Santa Claus.” It might be possible to regard this as camp if it weren’t so offensive. But Smith is also linked with one of the most repugnant examples of racist pop. “That’s Why Darkies Were Born” had been written for a show called George White’s Scandals of 1931, and it quickly became a favorite, covered by Paul Whiteman, the so-called “king of jazz,” among others. The song was so popular that it’s title became a gag line in a Marx Brothers movie. But Kate Smith had the hit, and her reputation suffers from it today.

“That’s Why Darkies Were Born” is a classic example of what some historians call “the carry-me-back” song, a tribute to the minstrel show tradition that, by the 1930s and ‘40s, survived in movie musicals of the sort that Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney starred in—sometimes wearing blackface. Under the pretext of nostalgia, these songs featured free blacks longing to return to the plantation. It’s no surprise that many whites back then were enchanted by the myth of the gallant South, but black artists weren’t entirely immune to its charms. A black composer wrote the former state song of Virginia, which pines for the land “where I labored so hard for old massa.” Major black singers performed “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South,” which describes slaves as “crooning songs soft and low” while dancing all night. Louis Armstrong included it in nearly every concert he gave. Whether these artists were looking to cross over, determined to alter the meaning of the lyrics by jazzing them up, or beguiled by the seemingly benign message of such songs is too complex to be addressed here. But it’s clear that Kate Smith played it straight when she sang:

Someone had to pick the cotton,

Someone had to pick the corn,

Someone had to slave and be able to sing,

That’s why darkies were born.

You can tell from Smith’s flimsy attempt to imitate a darkie accent that the narrator of this song is meant to be a slave who tells his brothers and sisters that “what must be, must be…. Though the balance is wrong, still your faith must be strong. Accept your destiny.” Here is the heart of what’s disturbing about those words when we hear them today. They acknowledge the injustice of the racial hierarchy, but they present it as a system grounded in nature. And then there’s another complication. The song casts slaves in a Christlike role, in which their faith stokes the train “that would bring God’s children to green pastures.” Sam Dennison, a historian of pop music, calls this “a gross horror of misplaced sympathy that can only be considered as among the worst songs ever written on the subject of black religion.” It’s also a typical representation of the double role that stigmatized groups often play. They are seen as inferior by design, but also possessed of magic powers that are sometimes sexual and sometimes spiritual. Welcome to the structure of Othering.

The question for us is: How could anyone ever have regarded this lyric as progressive? The answer is that, in 1931, many people did. One of the most important black progressives, Paul Robeson, recorded “That’s Why Darkies Were Born” with no evident irony. Robeson was outspoken on the subject of racism, but he never explained why he decided to perform such a song. It seems likely that its sentiments seemed heroic to him. We can see this attitude as complicit with racism, or we can regard it as a step in the evolution of consciousness. Both are plausibly true.

The same double meaning might be applied to Al Jolson’s blackface rhapsodies, or to the oblivious energy with which Garland and Rooney performed “Waiting For the Robert E. Lee,” whose lyrics invite us to view slaves loading cotton with affection: “Watch them shuffle along…join the shuffling throng.” American music contains many assumptions about race that are deeply disturbing now. To confront the reasons why Smith’s version of this repertoire was a hit is to understand that the meaning of a song is constantly changing. That’s why there are remakes, and why some sentiments once deemed heartwarming now seem unbearable. (Remember the Crystals singing “He hit me, and it felt like a kiss”?) This is what’s fascinating about exhuming old material—it’s like ancient light reaching us from afar. But the current crusade to strip the culture of offense prevents this encounter, and it sometimes makes villains out of those who were unwitting agents of a bias that millions of people shared.

Kate Smith certainly colluded with racism—and she profited from it. But so did many beloved performers whose work, if we dare to examine it, would relegate them to the same dustbin. I have more guilt than skin in this game, so I’m not about to suggest that Smith’s reputation should remain intact. But it seems to me that pouncing on a singer whose work violates our current beliefs, though it was once considered normal, offers only fake solace. It’s seductive to imagine that we can control the present by regulating the past, but in fact suppressing symbols is much easier than changing reality. We live in a world ruled by men, mostly white men, who are creating a world of new oppression. Policing the culture is a consolation prize for those whose freedom is slipping away, and corporations are quite willing to support that process—it’s much less risky than sponsoring actual change. So the next time you feel a surge of endorphins at the censoring of a derogatory song or the banishment of the artist who sang it, think of where we are and what it will take to “stoke the train that would carry God’s children to green pastures.” If you ask me, that’s why critics were born

Some of the material in this essay was taken from Darkest America: Black Minstrelsy From Slavery to Hip-Hop, by Yuval Taylor and Jake Austen.