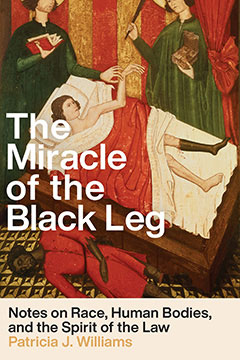

Patricia Williams’ The Miracle of the Black Leg, ends aptly (and elegantly) with a survey of the familial photo archive she recently deposited in a Harvard university library. She muses about “archiving as a social process” in her book’s final paragraph:

I yearn to have future beings see me and my wonderful forefathers and -mothers. We were all here! I wish them to live in social imagination more fully than many of them were able to while on the planet. And so I need to explain, I am constantly explaining. I am always looking for the right words, the right accent, the perfect analogy, the smoothest homology, the felt connection, the link that sparks a mental orgasm of humanizing recognition.

Williams squeezes out sparks in her chapter on her family and throughout The Miracle of the Black Leg. Try this extended excerpt from a passage on NOLA in a chapter titled, “The Dispossessed.” I think you’ll experience a kind of drawn-out “mental orgasm.” You may also cheer for Ms. Williams as she bites a hand that’s fed her.

I spent a few days in New Orleans recently. Years after the hurricane (and others that follow, follow, follow), it is still a city in mourning, as riven as ever. In 2000, before Katrina, the population was 484,674; in the immediate wake of the hurricane, the population fell by more than half, so that in 2007, it was a mere 239,124. An estimated 30 to 40 percent of the population never returned, most because they have not been able to; by 2020, the population was still only 383,827. Landlords refused to accept out-of-state housing vouchers from renters trying to return. Rents soared because of the decreased housing stock. Yet the New Orleans City Council demolished virtually all the surviving stock of public housing — large brick-and-mortar buildings, all minimally damaged, lots of windows blown out but all eminently reparable if there had been anything like an intelligent will. The tenants were never even permitted to go back in and retrieve their belongings.

Today, the Lower Ninth Ward is an eerily lush plain of overgrown sadness. Despite all the attention given to specific projects undertaken by architect Frank Gehry and actor Brad Pitt, the rebuilding has been sparse and terribly slow. Of the ward’s fourteen thousand residents before the storm, fewer than five thousand remain today. Only a few hundred buildings were sufficiently renovated for actual occupancy. Foreclosure rates were, predictably, staggering. I visited the city a number of times in the wake of the hurricane, and one of the more intriguing embellishments upon the expansive devastation was the flutter of hundreds of little signs affixed to the remaining lamp posts: EASY TERMS! REFINANCE WITH US! and WANT TO REBUILD? NO MONEY DOWN! Local newspapers were full of disturbingly gushy articles about Realtors who slavered over the historic row houses still standing in largely Black and poor areas. They saw the next SoHo! The new Chelsea!

To hasten the process of what one half calls gentrification and the other half feels as dispossession, the city passed an “anti-blight” ordinance. Little signs were planted in front of houses where only the walls remained. “Do you know where this owner is?” These signs pass as public notice: found owners are slapped with anti-blight fines. Failure to pay results in forfeiture of the land.

A year after Katrina, flooding caused levees to burst again, this time on the upper Mississippi, making mud of Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Radio commentator Rush Limbaugh (he used to be thought of as a “shock jock” but his legacy lives on as an American norm) snickered that the (largely white) residents there weren’t “whining” about their condition like those noisy (implicitly Black) New Orleanians. Well, it’s quiet in New Orleans now, a terrible brew of frustration beyond words and utter exhaustion. If it is just as quiet in the largely white floodplains of the upper Mississippi, we should not take that for a good thing in an economy as troubled as ours. The collapsed levees in Iowa and Missouri are signs of the same deeply broken infrastructure, even if the corruption that allowed it is not as visible, as cruel, or as racially inflected as in New Orleans.

American mobility depends upon the equity accumulated in its homes and the stability lent by reasonable rental stocks. The failure to make affordable housing a right has, in the long run of the last half century, hurt all Americans, leaving us with ravaged “inner cities” and strip-malled “havens” of suburban blight. As I experienced New Orleans while visiting in 2008, two models compete for our future, unfolding on the street. Model Number One: while walking in the Eighth and Ninth Wards, I saw scores of volunteers from all over North America, a rainbow coalition of mostly young people and college students, working for organizations like Habitat for Humanity. They were sweating in the broiling sun, hard at work, hammers in hand. Model Number Two: I overheard a conversation between two middle-aged men apparently touring the same area “for property deals.” The first was wearing an Obama T-shirt. The second said amiably, “So, you’re for Obama.” No, replied the first man; he was “a liberal,” but he hadn’t decided yet. It turns out he was a speculator in sheep’s clothing, just wearing the shirt to ingratiate himself with the natives — although ingratiate was not the word he used.

Poor us. The course we pursue may be politically disastrous, academically wrong, strategically flawed, statistically disproved — a cacophony of finger-pointing and calls to 911 — but our narratives instruct us to be stubborn guardians of the faith. At our collective peril do we remain enchanted by homiletic hokum about sifting wheat from chaff.

Of course, New Orleans is just one vulgar iteration of an inner city being “rediscovered,” “reclaimed,” and “repossessed” by moneyed interests. But the manipulations by which that has been and is being accomplished in New Orleans have seemed particularly convoluted and cruel.

So here’s an observation, about a subject I cannot yet translate into the domain of specific remediation. I offer it as…just a story, because the politics of what I am about to describe challenge me so profoundly. Indeed, my own involvement in it probably exemplifies a certain kind of well-meaning but troubling liberal paradox.

Recently, I traveled to New Orleans for an event that had been organized by an arts foundation I do some work for. I went as part of convening of nonprofit arts organizations from all over the country. whole event was part of an effort to support artists and artists’ spaces in that city, so many having been devastated in the wake of the flooding.

One of the events I attended was a spoken-word presentation under a tent, set up in a vacant lot in the Eighth Ward. The performances were very varied — song recitals by children, excerpts from plays with modern dance solos, poetry slams, and lots of bluesy music. Eventually, one woman rose and performed a long prose poem about her husband’s funeral. It was a lament for the passing of tradition. She had wanted a jazz band to accompany his casket through the streets, the way all the members of her family had always been taken home to rest. But since the flood, the city of New Orleans had imposed a fee of $5,000. It cost $5,000 to get a permit to play music in the streets nowadays, and she didn’t have that money, so her husband had to be buried without the fullness of the mourning tradition with which she always lived and had expected.

At the end of her elaborately and eloquently detailed presentation of the pain she had experienced, seemingly magically, members of a neighborhood social aid and pleasure club materialized — dressed in feathers and sashes, bearing trombones, trumpets, and tubas. They mounted the stage and began to play. They surrounded the woman, and then, still playing, not a dirge but a joyful recessional, they proceeded down from the stage, sweeping the woman along with them, and they marched out onto the street. The entire audience from beneath the tent, followed them, dancing, sashaying, trotting along to the music.

I had never been part of a so-called second line and considered myself very lucky. People poured out of their houses to join the line. I merged with the crowd that pulsed and surged and jostled like a giant snaky organism. Within what seemed like minutes, maybe two thousand people were dancing and pressed into this amazing, spontaneous formation; Indeed, two actual funerals joined along the way, and it was quite intense: women went into ecstatic frenzies, men spasmed, children shouted “Yes!” and “Go On!”

Anyway, it was hot and exciting and hypnotic, totally captivating because the procession went on and on, winding through street after street. As an innocent New Yorker, I had somehow imagined that we’d be going around the block and back to the tent again, so I was somewhat surprised when the brass band walked on and on through the unfamiliar streets — a quarter mile, half a mile, three quarters of a mile.

After a good long mile, the musicians suddenly stopped, took off their headdresses, and announced, “Well, that’s it, folks. This is where the money runs out.” There was genuine rage in the crowd, women crying, men shouting. A mini-rumble and grumbling of outrage rippled through the assemblage.

The musicians had led us right up to a police barrier — wooden saw horses and police cars blocked the street, and beefy officers stood with their arms folded.

Then, through all the chaos, there occurred a slow drifting of bodies, a traversing of the police line by nearly every white person in the crowd, as well as a very few people of color. And I realized that I knew nearly all those people who were drifting over behind the police barrier, because they were all fellow attendees at the very arts conference of which I too was a part, and they were beckoning to me, telling me to come over, cross over, to the other side.

Apparently the arts organization that had sponsored my trip to New Orleans had paid the $5,000 for the brass band permit. It had all been prearranged, to surprise us, to lead us like the pied piper from the spoken-word tent to the dinner afterward.

And, oh, the dinner. Beyond the police barrier was a narrow table that stretched for two long blocks, down a street of those beautiful old historic row houses for which the Eighth Ward is noted. It was a sit-down dinner for two hundred, one hundred people on one side of the table, one hundred on the other — so a very long, very dramatic table, set for a ten-course dinner, with candles and linens and crystal and waitstaff, set in the middle of this poor Black neighborhood, the residents sitting on their stoops as backdrop, like dark prophetic ghosts.

The dinner was billed as an art “happening,” an “event,” a “ritual feast” with “edible art,” and had been crafted by a local entrepreneur. It was an amazing sight, the table shimmering in white light, extending onward as though to an infinity point — the end point of that infinity being another police barrier two blocks away, at the other end of the table. All around me arose a murmur of appreciative “oohs” and “ahhs” from the assembled artists and museum trustees and curators. The waiters scurried about furnishing the guests with local plum glazed grilled alligator skewers “courtesy of Senator Sam Nunez” (who, rumor had it, had wrestled the beast to its death barehanded) and goblets of LaLeroux punch, described as a mixture of old New Orleans amber rum, brewed chicory, pressed ginger, fresh mint, local honey, and jalapeno. I got a copy of the menu before I left, and the names of the courses were intriguing. “At the Crossroads” consisted of absinthe in heart-shaped flowers, with vermouth, egg white froth, and hand-gathered, solstice-charged spring water. “Now Become Creole” consisted of Napoleon’s roasted squab, heart of watermelon, and lucky black-eyed peas with 130 monk-made herbs, pickled rind compote, and popcorn sprouts. And the course labeled “Into Purity” consisted of chilled almond-milk soup with carbonated grape, and white chocolate-dipped sugarcane.

But, as I said, I did leave. I could not make myself sit down at that table. I couldn’t quite work up an appetite beneath the weight, the simmering gaze of the people who actually lived there, gathered somberly on their stoops, little children on roller skates and bikes, gliding up and down the sidewalks, asking for samples from the caterers and being told that it was a private event on that public street, and that there wasn’t enough. I left in a cloud of…something for which I have no name.

Having no idea where I was, I passed back to the other side of the police barrier and got on an empty bus, one of a fleet chartered to return guests to the hotel after the festivities. I convinced the driver to take me back early. I sat in the darkness, talking to the driver, who had been a driver the infamous night of the evacuation from the New Orleans Convention Center. She told me that the woman who stages these banquets — for there had been more than a few before this — was not really an artist, but a real estate agent, and that she was trying to bring artists into the Eighth Ward to rejuvenate it, gentrify it. And that those somber residents liken her events to Klan rallies. And that she for one — the bus driver, that is — did not like people who drank hand-gathered, solstice-charged spring water.

The bus driver told me stories about the night of the evacuation, that grievous diaspora to all points — and nowhere, some destinations still unknown. She told me that the hardest moment was when she had to argue with a National Guardsman about letting a woman board the bus with her just-deceased, still-unwashed newborn. The National Guardsman kept calling the body a biohazard and refused to let her board unless she discarded the child, literally threw the body away. My bus driver said she’d convinced the Guardsman to let the woman wrap the child in the shroud of a plastic garbage bag and place the body in the baggage compartment under the bus.

She regaled me with even more such tales all the way back to my fancy hotel, where I tried to sleep amid the fluffy silken pillows, pondering this reiterated national narrative of forced migration, of homelessness and exile.

…

Copyright © 2024 by Patricia J. Williams. This excerpt originally appeared in The Miracle of the Black Leg: Notes on Race, Human Bodies, and the Spirit of the Law, published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.

The Miracle of the Black Leg – New Press