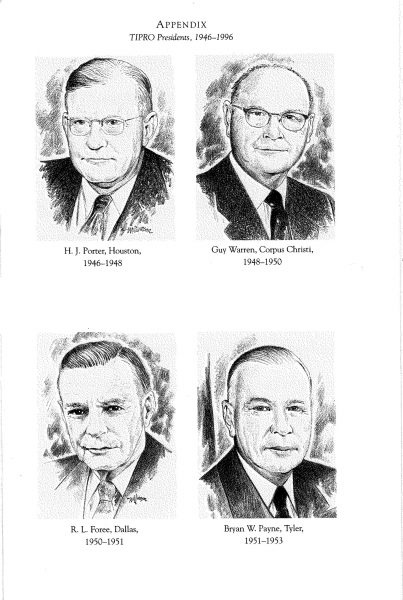

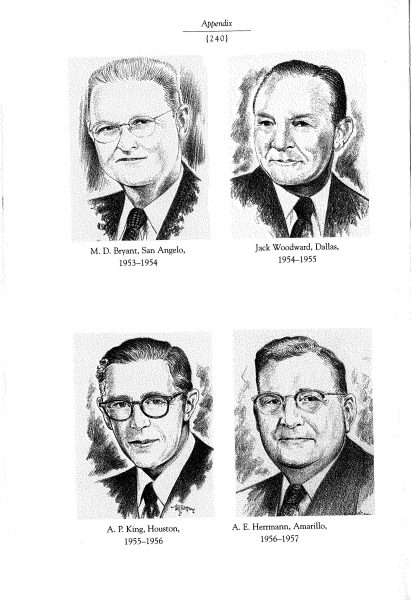

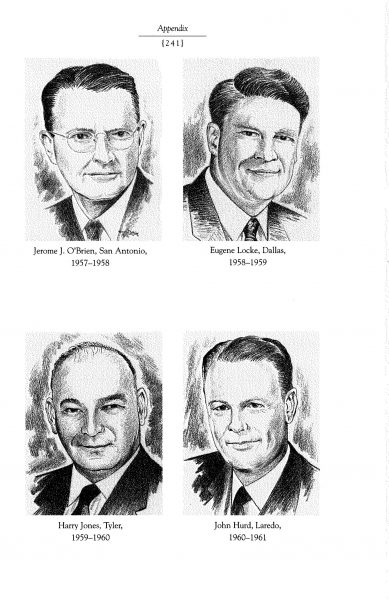

“Larry Goodwyn has a book out there that nobody talks about.” I was struck by Donnel Baird’s nod in People Power to Goodwyn’s Texas Oil, American Dreams: A Study of the Texas Independent Producers and Royalty Owners Association. Keep in mind Baird is a young black organizer-turned-entrepreneur who runs a venture capital backed startup focused on bringing clean energy and economic development to places like Harlem, where his business is based. (“We are building solar-powered microgrids in New York City’s poorest neighborhoods.”) Now take a look at the first few pages in the portrait gallery of presidents of the organization, TIPRO, that Goodwyn lauded in Texas Oil, American Dreams.

Baird, like his beloved mentor Goodwyn, belongs to that permanent counter-culture who realize that a life in struggle must be founded on resistance to received ideas–such as the notion a young blood has nothing to learn from old white men.

Goodwyn boiled down his own rationale for writing a book about TIPRO in a footnote. He began with a respectful invocation of Robert Wiebe’s overview of America at the turn of the 20 C., The Search for Order, which limned how the “entire subject of large-scale concentration in the U.S. economy inevitably immobilized public officials, who faced real problems as distinct from theoretical ones.” Goodwyn zeroed in on one hero of early 20 C. progressivism, noting that Robert La Follette failed to come up with a program worthy of his call for a “sweeping antimonopoly crusade.” But Goodwyn wasn’t out to bash Fighting Bob: “The entire issue of economic centralization of the American economy is one that has historically confounded scholars as well as political observers.” That, in turn, explains why Goodwyn tried to get TIPRO’s history into the national conversation: “It may be said that the internal records of TIPRO constitute–in terms of detailed evidential concreteness–one of the most remarkable sources of historical evidence available anywhere in the nation as to the negative impact upon independent entrepreneurship of large-scale economic concentration in America.”

So in Goodwyn’s telling, TIPRO–a trade association of independent Texas oil and gas men–belonged to the true vine of American anti-monopolism. Just like the 19th C. agrarian insurgents whose achievements he’d memorialized in Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America.

TIPRO was in Goodwyn’s tradition, but that wasn’t the only thing that got him gushing. He liked surprises…

…suddenly, it happened. Without warning, a sudden roar could be heard, immediately followed by a volcano of mud, rocks, gas, and oil rocketing hundreds of feet in the air.

Absolutely no precedent existed for the scene that engulfed the Hamill brothers, and it took several minutes for its meaning to set in: an enormous continuous surge of petroleum roaring out from the depths of the salt dome, cascading hundreds of feet in the air and drenching the entire countryside in a black mist…

It spewed somewhere between 75,00 and 100,000 barrels a day for nine days–the staggering total of 600,000 to one million barrels–before a vastly expanded workforce and an increasingly frantic drilling crew could get the torrent capped. It was, indeed, “the biggest” and the most “unimaginable” oil well in the history of the world.

Goodwyn begins with the story of that “Spindletop” well. He tells what happened to wildcatters who drilled it and how they had to deal (before and after) with money-men back East. The Spindletop gusher would result in the founding of Gulf Oil company, but Goodwyn makes it clear the imperatives of wildcatters brought them into conflict with major corporate interests right from the start of the Texas oil boom. He moves on to the tale of another legendary well in East Texas’s piney woods–crafting a real romance that shames Capra-esque fantasies. As the Depression was coming down hard, a wildcatter named Dad Joiner got a whole county invested in his willful effort to keep drilling, though experts insisted it was pointless…

Everyone was strapped so they just shared the poverty. Joiner kept a crew by feeding them. He got the food because the Overton grocer accepted Joiner’s script against future production. So did other merchants…

The town banker in the nearby hamlet appeared regularly (after banking hours) to don overalls and go to work. His wife cooked for the crew. When the rig was shorthanded–a chronic condition–sympathetic cotton farmers would take a day off and lend a hand, often on the chance they might get something to eat. As the Depression summer of 1930 passed and winter loomed, Dad’s well was about the only thing people had to look forward to.

A reader looks forward with them until “the slowest well in Texas” finally comes in. It’s a…populist moment.

But Goodwyn isn’t content to update old verities. He keeps surprising you even when the action moves from woods to Swamp. In one unexpected turn, he tells how Senator Lloyd Bentsen, with a lot of help from TIPRO’s staff, made himself an expert on energy legislation, enabling him to teach Congress to take in the difference between massive oil companies and independent producers. In Goodwyn’s account, Bentsen becomes a larger figure than politicians like Wright Patman who were known for their anti-monopolist rhetoric.

I’m flashing back to 1988, when Dukakis chose Bentsen as his running mate, instead of Jesse Jackson. I thought that was a cowardly move. Senator Bentsen seemed like a bland Establishmentarian. Leave it to Larry to make me see Bentsen through reverent eyes:

“I think there are times in the lives of some specially gifted legislators when they sense that the balance of forces is such that their own individual effort can make a decisive different on a major issue affecting the whole nation. The pressure is intense at such times…I rounded the corner and saw him under a light down at the end of the hallway, with his arms spread askew, looking up almost as if he was praying. He stayed that way for some time…the next day, Bentsen delivered on the Senate floor the most comprehensive depletion case ever presented before Congress. It was absolutely magisterial.”

I’ll end with another paean. Texas Oil, American Dreams was the last book Larry published and it includes his loving last word on Nell Goodwyn’s contributions to his work. He told how she’d helped him sort through hundreds of pages of interview transcripts, supplying notes that “proved to be an invaluable guide through a mountain of material…

Additionally, as always, I wish to acknowledge the consummate editorial and critical review the final manuscript received at her hands. This is the sixth time we have engaged in such a joint literary effort, and, as always, I am conscious that a mere public acknowledgement of her editorial discrimination, no matter how phrased, constitutes a wholly inadequate attempt to convey to others the centrality of her role. One fact is at least suggestive: she was instrumental in the naming of the book–as she was once before in our shared endeavors.