Winslow Homer’s painting “Near Andersonville” faces the first page of text in Perspectives by Incongruity — the new volume in the First of the Year series (which you may order now — see link under the cover photo on our homepage). History is moving fast, but with the GOP’s latest great white hopes competing with hot Mitt to stoke rage at Obama-the-alien and the First (Angry Black?) Lady getting caricatured in the media, Homer’s portrait of that Sister thinking her way out of danger is still timely.

Jesymn Ward’s essay here on facts of black-and-going-on feeling, “Blood Dread,” which she wrote back in 2008, is news that stays news too. Ward explains she was slow to back Obama’s campaign then, unable to believe he was a viable candidate due to her own coming of age in Mississippi. Where she learned to put a priority on less-than-civil resistance to racism:

you look at the…one that threatened you with lynching or beating or burning, with all of the ghosts of the south on his shoulders, his jock-buddies around him, him you looked in the eye and you said, no, you won’t do shit to me. Try me.

Her meditation on Mississippi learning takes in her family’s “bone memory” of humiliation and endurance. Her ancestors’ legacy — “They’d eaten hope. Starved for it. Died for it.” — helped her overcome her doubts about Obama’s prospects (and America’s): “So I voted for him.”

Ward’s movement of mind isn’t locked on self (or even family). It leads to a wider affirmation: “And so did you. And he won.” Heading into the next election, though, Ward’s assumption “you” are on her aspirational side seems almost beamish. (Aware of “enthusiasm gaps” among potential supporters, the president himself has mused his toughest opponent this year might be Obama-in-2008.) Yet Ward’s sense of commity should remind white liberals and radicals what’s at risk if they walk out on the party of hope.

Not to worry, I’m not about to channel actor William Forsythe in Patty Hearst when he voiced the darkly comic credo of Symbionese Liberation Army’s dim white grunts: “What we need is some black leadership.” (Though I’ll note that line has taken on a new weight in the wake of Gaddaffi’s fall — S.L.A.-style Third Worldist thuggery was more than a horrorcore joke overseas where monsters like Gaddaffi used Pan-Africanism as one cover for terrordomes, so it’s a not-so-tragic irony he went down last year thanks to black leadership… from behind.[1]) Lord knows it’s long past time to say good-bye to radical chic (reactionary-in-fact) lust for macho charismatics of color. But nobody should mix up such yens with African Americans’ will to represent themselves. There’s nothing derisory about that desire. Nor is it a lie to hope black folks’ history might make their representative man (and woman) more alive to injustice (and cannier about resisting it).

The proof is in “Obamacare.” See Paul Starr’s chronicle of the hundred-year effort to enact universal health insurance, Remedy and Reaction (and Bernard Avishai’s Nation review). Starr’s account clarifies (in Avishai’s words) “how sensible and brave was the president’s effort to drive the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 through Congress.”

When Obama came into office, Starr explains, only 11 percent of Americans thought reform would have a “negative personal impact,” but by August 2009 this segment of the population was trending toward 31 percent. Both Rahm Emanuel and Joe Biden were urging retreat. Starr writes, “Obama not only chose to go ahead; in September and then again in the new year, the president took charge of the effort to steady the health-care initiative and prevent it from careening off the tracks.” Nor was the final bill anything less than what might reasonably been expected, filling as it did the negative space left by four generations of government programs and serial compromises.

Obama fought wisely and well on behalf of America’s most vulnerable citizens — contra those progressives who trashed his compromises, though they never had votes to pass their beloved public option (which, as Starr shows, wasn’t necessarily the best option anyway).

Obamacare — a once-in-a-lifetime legislative achievement — makes the strongest case for the president’s leadership and capacity for sustained attentiveness. But, like most of us, he isn’t always up to the job of improving America’s public discourse. One of the sharpest critics of Obama’s words and deeds nailed the president for a careless moment at a White House Correspondents’ dinner where he made an unexpected joke:

“Jonas Brothers are here tonight. Sasha and Malia are huge fans. But boys, don’t get any ideas. Two words: predator drones. You will never see it coming.” The line caught a laugh but it should have caused an intake of breath. A joke (it has been said) is an epigram on the death of a feeling. By turning the killings he orders into an occasion for stand-up comedy, the new president marked the death of a feeling that had seemed to differentiate him from George W. Bush.

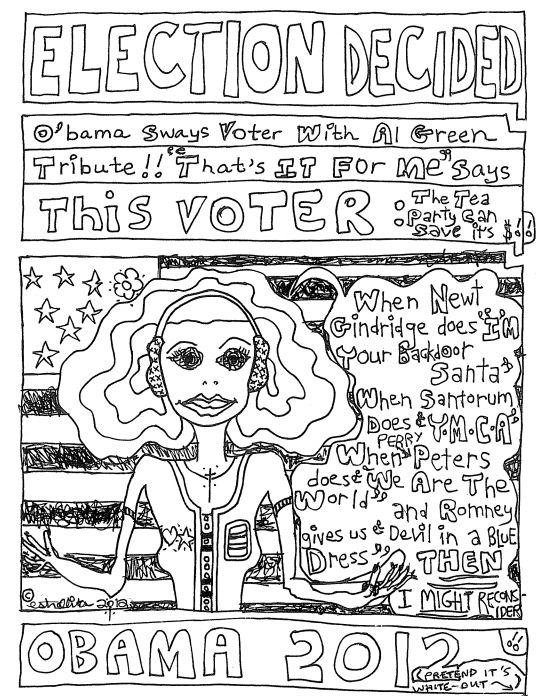

Obama’s slip into brutalism notwithstanding, his difference from his predecessor(s) is out there for all to see and hear. As it was last week when he sung a bit of Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together” at the Apollo. Which sparked this sweet comic response from “undecided” Virginia voter and First contributor, Carmelita Estrellita:

Estrellita is a creatively marginal white southerner whose psyche may not be the most reliable guide to the state of the electorate, but anyone who doubts Obama’s base will be stoked should pick up on massive emotion engendered by video of the pres’s vocal riff. The title of an album (post-prime but still sublime) by Obama’s inspiration is on point here: Al Green Is Love.

Jesmyn Ward shares her love for America’s Brother-in-Chief in “Blood Dread.” Ward is not an outlier on this score. Her National Book Award-winning novel, Salvage the Bones, about motherless black children surviving rural poverty (and Katrina) with their daddy (and pit bulls), proves there’s nothing she doesn’t know about down home familial emotion. Ways of Southern white folks aren’t foreign to her either. Literary blogger, Liz Johnston, notes Salvage the Bones’ narrator invokes As I Lay Dying, which she takes as a cue to link brothers (and other male characters) in Dying with Bones’ boys in the bayou. To this close reader, though,

what makes thinking about Salvage the Bones in comparison to As I Lay Dying truly compelling is Ward’s narrator, Esch. Poor, motherless, and pregnant, Esch definitely resembles [Faulkner’s] Dewey Dell…but Ward transforms the character into someone tough and beautiful.The few chapters Dewey Dell narrates in As I Lay Dying are almost incoherent and might remain practically indecipherable were there not male narrators to tell us what happens to her. In contrast, Esch gets to tell her whole story in Salvage the Bones and does so quite eloquently.

Bones’ bows to Faulkner are more than lit’ry auteurism: the author (as per her critic) “seems to be giving voice to perspectives Faulkner marginalizes.”

There’s always a need.

Especially when the most imaginative mind on today’s New Left, David Graeber, ain’t trying to hear from Obama lovers with Southern accents. Graeber has urged Occupy Wall Streeters to step off from the president without, perhaps, fully taking in felt consequences of divorcing America’s new radicalism from Obama’s African American base.

Graeber’s an anthropologist and maybe he should think like one when considering what having Obama upfront-and-center on the national stage means to black “dis people.” To borrow a phrase from ethnographer John Chernoff who elaborated on it as follows: “In the big picture, where history and money are being made, [dis people] are apart and away from the centers of power, out of it, utterly and thoroughly. The prefix ‘dis-,’ which dictionaries say means all of the above, attaches to their names with appalling reliability: disenfranchised and disadvantaged, disaffiliated and disinherited, discomfited and discredited, displaced and discarded, discussed and discounted, dispossessed and dismissed.” Chernoff was writing about West Africans, not African Americans – he came up with his phrase before the term diss went international. Still there’s a reason why his stories of an African bar girl and dis people in her world won a Herskovits award. The West African culture of solidarity (and poverty) he evokes below has its felt equivalent on this side of the Black Atlantic. (Read Salvage the Bones if you doubt that.)

These are the people who are last in line, those without the opportunity to participate in the universal grabbing. They have no choice but to manage with patience. Despite the chicanery at every turn, they hold strongly to a fragile fabric of social decency. Their approach to life is characterized by every type of exploitation but also every type of altruistic kindness. How else can one account for the survival of the common people? No economist has ever figured out how they make it from day to day…It is a situation that would turn us into gunslingers, and instead, people somehow hang together and get by. The society may be disorganized, but the people are not in disorder. Under pressure from modern life, the old strengths of the traditional societies continue to support the social vessel. The extended family offers shelter to the castaways, and the mentality of the extended family reaches into the urban scene where people from different ethnic groups call each other “brother” and “sister.” The traditional ethic of redistribution ensures that if there is little money to begin with, then at least the money that is there will move at an incredible velocity. Sharing is everywhere — sharing a room, sharing one’s clothes, sharing food, sharing a cigarette, sharing a laugh, sharing a moment in the evening breeze. Under the pressures of modern living at its worst, the inherited values of the people do not break, though they often bend.

David Graeber has upheld those values in his deeply humane book Debt: The First 5000 Years. He’s helped tune us in to what he calls a “communism” of dailiness — structures of feeling that persist beneath the cash nexus in capitalist societies (and in top-heavy “workers’ states” too). While it’s no wonder Obama’s relatively genteel attempts to counter G.O.P. bootstrap crap aren’t Graeber’s meat, it’s hard to see why he’s entirely unsympathetic to the president’s rhetoric of caring and sharing.

Then again, on the real side, Obama’s vision of communitas lacks fresh content (except when it comes to healthcare). He — and we! —could use an original concept. Something like what Gar Alperovitz projects when he talks of a “Pluralist Commonwealth” — an organic alternative to corporate capitalism (and state socialism) based on worker ownership and a democratized financial system. Alperovitz’s model is aligned with best practices of past generations of American populists and vital contemporary thinking about political economy (pace William Greider, Lawrence Goodwyn et al.). What matters more now, though, is the Pluralist Commonwealth may be busy being born in a swing state! (See Alperovitz’s comments on the Evergreen project up and running in inner city neighborhoods in Cleveland.) Proponents of worker ownership and wide-scale community development might have a shot at reaching Obama in an election year. Wouldn’t he be up for rocking a Cleveland project ripe with potential for serious structural change?

The question now is what can Obama (and feds) do to push the program? I’m guessing Alperovitz and his allies in Ohio have answers. And I hope David Graeber and OWS types who mainsteamed thinking beyond capitalism and state socialism will hang tight with those who could make the ideal of commonwealth real for Obama.

Let’s stay together.

Note

1 Gaddafi boasted back in 2008 Arab money-men were responsible for Obama’s election. Perhaps even right-wing rumor-bloggers will concede that add-on to the Manchurian Candidate meme has gone to dune.

From February, 2012