My old friend Charlie Keil emailed me–“See why you like Kanan Makiya. Love those lions.”–after he read Makiya’s recent piece in the Kenyon Review, “The Dying Lion.” Keil’s responsiveness speaks to his intellectual honesty since he had to think against himself, beating his own bias against Makiya who famously supported the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which Keil thought was immoral (and dumb).

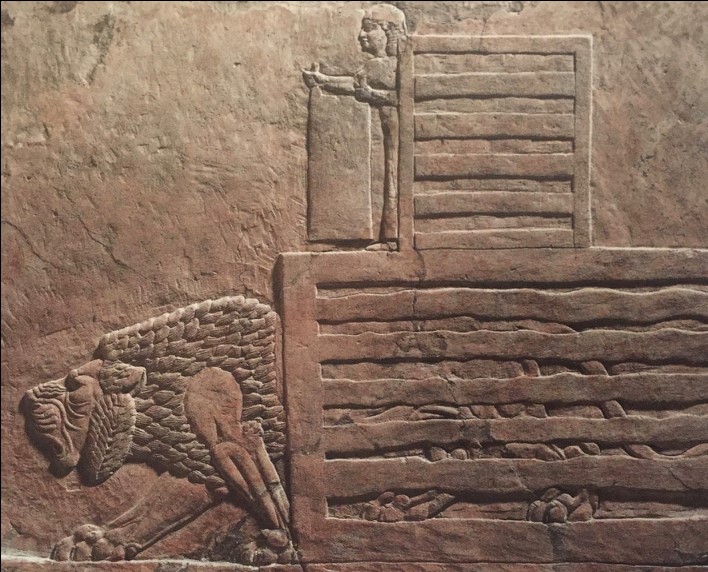

“The Dying Lion” earns Keil’s stretch. Makiya bows to an anonymous ancient Assyrian sculptor from the seventh century B.C. who put cruelty first among evils–cultivating the uncreated conscience of Middle Eastern peoples. This unknown artist (or artists) carved images of royal lion hunts replicated in the British Museum’s Assyrian galleries. That term “hunts,” however, may be misleading. What’s depicted in the Museum’s copies of the original gypsum and limestone panels was an event where a king displayed his power by killing big cats who had already been captured. The following carving of a little boy opening one lion’s cage before getting back into his own hints at the nature of the spectacle.

I’m with Makiya when he argues the anonymous sculptor who made the original images of these ceremonies wasn’t neutral about what he witnessed. On the walls of the palace of his master, this outsider artist managed to put up stone protests against a vicious ritual of kingship—protests that are still on time thousands of years after the acts of cruelty they evoke.

Not that Makiya heard the roars of silence right away. For years he walked by the British Museum’s lions in extremis without taking in the pain on display. This is the one he felt first…

In “The Dying Lion,” he links this animal’s sensations—the blood gushing from the mouth, that one piercing arrow that goes right through the shoulder to your heart—with his father’s agonizing death in 2015. But he reaches beyond the personal to historical/political quintessences. He connects the lion-killer to those hard men who keep coming in places like Mosul, which is located near the ancient city of Nineveh where Makiya imagines his hero-sculptor working against the grain of kingly and priestly cruelty. That anonymous artist rendered a Middle East power-monger of his day. And Makiya urges us to compare faces of the dead and dying lions with the face of the king who had just killed them: “Here he is…in the tall, conical hat that identifies him as the absolute authority in the land…

“The lion,” Makiya notes, “is in pain; the king is all poise and erect, expressionless…”

The lion’s eyebrow, nose, and cheek are wrinkled up as he turns in on himself, spewing blood. Yet the king is unflappable; he is order and politics incarnate. One can, I want to suggest, literally see intense feeling in the one and its absence in the other. In a different life I was an amateur sculptor and can confirm from personal experience that what this unknown Assyrian artist from bygone times that I’m putting on a pedestal has done is extremely hard to do—and hardest of all in stone.

Makiya believes his anonymous artist/craftsman wanted “others to feel [pain and suffering] through his work and empathize with the lion, not the killer.” That kind of empathy has defined Makiya’s own life and work ever since 1991 when he met Kurds who had survived Saddam Hussein’s mass murdering Anfal Operations. Makiya became a defender of felt life then. “The Dying Lion” proves he’s keeping the faith. Though I’m sure he’s been tempted to give up given what’s been happening in his country of origin. Makiya talks straight to those who assume it’s an Orientalizing fantasy to invoke a “Mesopotamian penchant for cruelty”:

Consider, for instance, the notion that many Iraqis hold of themselves that they positively need to be ruled with an iron fist…Consider also the nostalgia that has grown alongside the violence of daily life in post-Baathist Iraq for the good old days of Saddam Hussein…Such self-deprecating views of the collective Iraqi self will once again be reinforced when the full scope of ISIS’s savagery inside Mosul and the rest of Iraq and Syria becomes evident, and if the Shia’ militias running loose in Iraq are allowed to loot and level Sunni homes inside reconquered Mosul as they did in Ramadi, Beiji, and Tikrit.

Makiya doesn’t sound confident powers that be in Iraq will finally restrain vengeful tribal warriors (which may be one reason why he’s into long views and outsider sculpture). God knows there’s not much reason to be cheery about Iraq’s future.

OTOH, Barham Salih—my favorite politician in the oughts (pre-Obama)—is back. He became president of Iraq last October and he’s been using that ceremonial position to resist American hegemaniacs, Arab supremacists and Muslim sectarians. He’s out to embody (as ever) a vision of Iraqiness even as he celebrates his Kurdish roots. Salih’s twitter feed recently memorialized his dicey trip to a Sunni neighborhood in Baghdad that had been off-limits to Iraqi politicians (Shia’ in particular) and then offered up a charming travelogue of a Kurdish New Year’s festival.

Salih himself was prime minister of Iraqi Kurdistan for a time but his career there had downs as well as ups. Back in 2017 he tried to start a political party, which didn’t get traction. He ended up reconciling with the PUK—the party of his mentor, the late Jalal Talabani. Salih’s return to the PUK has led some Kurds to bash him as an unprincipled opportunist. But it may instead be a sign of Salih’s own forbearance—his Talabani-like readiness to work with anyone who might help Kurds and other citizens of the new Iraq overcome Middle Eastern legacies of terror/tyranny.

Salih’s instincts have never been narrowly tribal. He first came to my attention in 2003 when he spoke in favor of the coming American invasion of Iraq in a speech to the Socialist International who met in Rome that year. (Salih reminded Italian delegates their country had needed outside help to oust their tyrant Mussolini.) Once the American invasion was on, I watched Salih (on CNN) in the streets of Kirkut, herding Peshmerga out of the city. He wanted to make sure nobody got the idea Kurds would use the invasion as a pretext to lay claim to Kirkut—the oil-rich city that remains disputed territory in Iraq.

It was Salih’s presence that convinced me I must support anti-fascists in Iraq who were intent on overthrowing Saddam by any means necessary. I’m reminded of the musings of a liberal commentator back in 2006 (a few years after his own “disastrous decision”). He invoked a familial Q&A to explain how he ended up in the same sinking boat I jumped into: “’Why, exactly, did you support this war?’ asked my wife the other day…For myself, perhaps the most honest reply is this: because Kanan Makiya did.” In my case, Salih was the decider.

While I was moved by Makiya’s case against Saddam and for democracy in Iraq, I sensed Salih was closer to the real. He wasn’t an exile like Makiya (though he escaped to London for a time in the 90s after being tortured by Saddam’s goons). He represented an actual constituency on the ground in Iraq. (When Salih was marching with Peshmerga who played an important strategic role during the American invasion, Makiya was stuck way behind American lines with an unbrotherly band of exiles led by that con man Ahmed Chalabi.)

There was a time when politics in Iraq mattered more to me than politics in my own country. That was then (though I’m not suggesting my foreign affair is beyond contemporary judgement). Trump will surely concentrate most of my attention (and yours?) for the foreseeable future. Yet it’s never a waste of time to feel like Kanan Makiya. And we should aim to keep up with P.M. Salih too.