What follows is an excerpt from the late Stuart Hall’s Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands (2017). First is posting it with the permission of Duke University press which holds the copyright.

‘Suddenly everything looked different.’ That’s how I earlier described the effect of my seeing West Indians, dispossessed folk most of them, spilling out of Paddington Station days after I myself had arrived in London. It turned around every preconception which lived inside me. The prerequisites of the colonial order had placed us here and them there. That was the preordained state of things. And yet now – in London, in front of my eyes – I could see in that instant the world turning inside out. I was mesmerized. It was as if the ‘real’ Caribbean which at home had remained beyond my reach had come to meet me in, of all places, England. Although I didn’t have the mental means to explain what I’d witnessed, I somehow knew that what I’d seen changed everything. It marked my instinctive, unworked-through commitment to what later came to be called a diasporic conception of the world. I felt as if that scene had literally imprinted itself on my mental retina. I still remember every detail. It altered the possibilities I possessed for understanding who I was and who I might become.

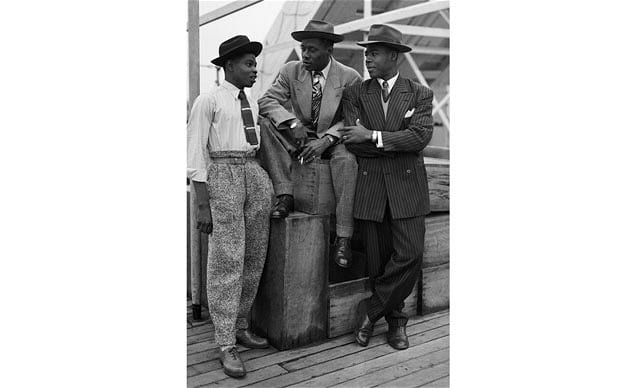

At home we have in the hallway a huge reproduction of a news photo taken on the Windrush of three Jamaican migrants – two older men, carpenters, and one younger, an aspiring boxer – in their formal, sharp gear ready to step off the boat and make their entrance to the mother country. The older ones are wearing double-breasted pin-striped suits and felt hats, at a rakish angle. The younger man is in heavy salt-and-pepper trousers – drapes, the height of fashion at the time – which were baggy at the knees, tapered to exaggerated turn-ups, and sports a hat with the brim upturned all around. This was style. They were on a mission, determined to be recognized as participants in the modern world and to make it theirs. I look at this photograph every morning as I myself head out for that world.

A while ago, at the opening of an exhibition of Windrush photos at the Pitshanger Gallery, Mark Sealy, the director of the charity Autograph ABP, invited me to say a few words of introduction. I was overcome by the emotional weight of the images which surrounded me and by the memories of the varied fortunes of my migrant generation. We’d all undertaken the journey to our many illusions. Embarrassingly, I found myself in tears. The experience of seeing difference played out in front of me was formative: I understood that difference was not to be evaded. I have continued thinking about this ever since. Standing at the juncture between a Jamaica to which I wasn’t sure how to belong and an England to which I knew I didn’t belong, the diasporic scene and its lived incongruities provided me with a space in which to think, a place on which to stand.