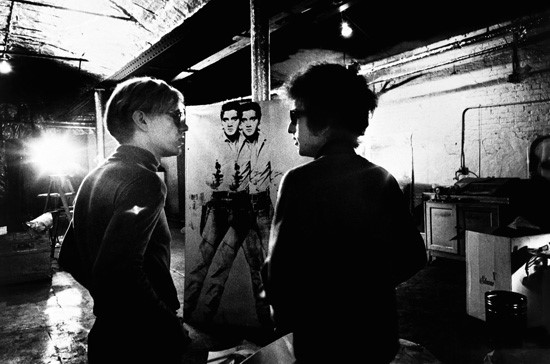

Nat Finkelstein’s photograph of Warhol, Dylan, and Double Elvis

As far as anyone knows, Dylan and Warhol met only one time of any consequence, fifty years ago near the end of 1965 (the exact date is unclear), at Warhol’s Silver Factory on East 47th Street in New York City. Some facts about that meeting are well documented. Dylan sat for two of Warhol’s “screen tests” — the four-minute silent films Warhol made in the mid-60s (approximately 500 in all), where a fixed camera was trained on a seated subject who had no script and little direction. Both artists also posed for the photographer Nat Finkelstein, whose photographs of that day include a well-known shot of the two in front of Warhol’s silkscreen Double Elvis (1963). Dylan left with the larger-than-life-size Elvis canvas, maybe a gift or maybe barter offered in exchange for the screen tests. In a photograph taken by Finkelstein from the Factory’s fourth-floor window [see below], in the lower right-hand corner, almost out of the frame and easily overlooked, you can just make out a white station wagon with Elvis’s image roped to the top like a mattress.

Finkelstein’s photograph of Dylan and Warhol together in front of the Elvis silkscreen is a famous image, although also a puzzling one in certain respects. It’s difficult to figure out what to make of the meeting recorded by the image because Dylan and Warhol are dramatically different sorts of artists — different mediums, different idioms (blues and pop), and ultimately different sensibilities. Dylan’s anxious but wolfish heterosexuality is difficult to imagine mixing easily with Warhol’s fey queerness. And the metaphysical flatness of Warhol’s silkscreens and Brillo boxes operates in a different perceptual arena than Dylan’s serrating songs. Certainly, neither liked to be upstaged. One might guess that it was little more than happenstance that they met at all. They were simply two famous people sussing each other out.

The Finkelstein photograph of Dylan, Warhol, and the Double Elvis thus seems more like a publicity shot than a record of a meaningful connection. This understanding of the meeting has been underwritten by the prevailing impression that Dylan and Warhol simply didn’t like each other very much. In Finkelstein’s other photographs from that afternoon, they seem to circle each other like two cats. Dylan later traded the Elvis silkscreen for a couch. Warhol soon made an ill-spirited mockumentary film, The Bob Dylan Story (1966), and included in his book Andy Warhol’s Index (1967) a poster-size foldout photograph of Dylan’s silhouetted profile in austere black-and-white but with an oversized fuchsia nose. The nose folds back to reveal yet another colored nose, this time multicolored, which then folds back to reveal Dylan’s actual nose.

In other words, it’s hard to imagine the meeting as a connection of two creative forces or an exchange of ideas. Nothing seems exchanged other than perhaps a competitive aggressiveness. Dylan arrives, Dylan restlessly sits for two screen tests, Warhol shows the Double Elvis to Dylan, Dylan leaves with the Double Elvis, and photographs are taken along the way. The meeting hasn’t generated much fruitful commentary in the voluminous writing on the two artists. Thomas Crow’s magisterial The Long March of Pop (2014), which presents Finkelstein’s famous photograph twice (at the beginning and near the end), is the exception that proves the rule, but Crow shows less interest in the meeting per se, focusing more on arguing for Warhol’s (and Pop Art’s) foundation in the folk tradition. Commentators on Dylan rarely mention it (Greil Marcus, one of the best critics of Dylan’s work, not at all). Warhol’s biographers have tended to concentrate on the complicated relationship that developed between the Warhol and Dylan factions over Warhol’s star of superstars, Edie Sedgwick. Although the details remain unclear, Sedgwick eventually left the Factory fold, perhaps because she believed that Dylan’s Mephistophelian manager Albert Grossman could provide her with some career options that Warhol’s underground films could not. Much of the inquiry into Dylan and Warhol together as imaginative artists has been limited to fandom conjecture on, say, whether Warhol inspired the “diplomat” in 1965’s “Like a Rolling Stone” (because he “carried on his shoulder a Siamese cat” and Andy loved cats) or whether the girl in “Just Like a Woman” (1966) — with “her amphetamine and her pearls” — is the strung-out debutante Sedgwick. Perhaps. Warhol and Dylan haven’t come together in more significant ways in our accounts of late twentieth-century culture because they worked in different mediums and possessed dramatically different sensibilities, but also because of the “break” narratives which make Dylan especially but Warhol also into individual, rather than collaborative and reciprocating, visionaries. These narratives are well known and ritualistically retold to an extent that suggests that they are essential to the self-understanding of many, perhaps even a generation of, observers. Dylan “splits the sixties,” as the subtitle of Elijah Wald’s recent Dylan Goes Electric! (2015) puts it, breaking from the Weltanschauung of folk music, just as Warhol breaks from abstract expressionism. They are rebels, not collaborators (even if they do work with bands and artistic assistants), and these popular narratives sit in some degree of tension with the idea of artistic exchange.

Nevertheless, I have always been drawn to the encounter, especially Finkelstein’s images of that afternoon, and more particularly his image of Dylan, Warhol, and the Elvis silkscreen. That photograph, as famous as it is, has escaped close analysis. For me it suggests a moment in history that has remained potential rather than becoming actual. A kind of counter-moment — counter to the blinding aura of celebrity which now radiates from it, and counter to the individualizing narrative of radical genius — where Dylan and Warhol are thinking together, in a reciprocal relationship, in a kind of collaboration.

A good place to begin is with the simple question: how did Dylan and Warhol end up in the Factory together on that afternoon fifty years ago? The first-blush answer is fame, of course, but for both it was a new kind of fame. The year 1965 marked a transformative time for both artists. Warhol and Dylan shared the experience in ’65 of their essentially art-world and folk-world scenes going mainstream. They became mass media stars and principal actors in the post-war era’s unprecedented expansion of the culture industry. In the spring, Dylan’s take on anti-establishment scenes in “Subterranean Homesick Blues” resulted in his highest charting single to-date. The initial success of “Like a Rolling Stone,” the controversial electrification at the Newport Folk Festival, and the release of Highway 61 Revisited followed before Labor Day of 1965. Warhol, for his part, by 1965 had already created what would become in retrospect his most iconographic images — the Campbell Soup cans, the Marilyns, Lizes, and Jackies, the Brillo boxes and “disaster paintings” — but 1965 still marked unprecedented mass publicity. Life, Time, Merv Griffin, Walter Cronkite’s CBS News, and the Canadian Broadcasting Company all came calling. In October of 1965, Warhol and his entourage from the Factory were mobbed by a group of 2,000 students during the opening of his first American retrospective exhibition at the University of Pennsylvania, an event more like a rock concert than an art opening.

But Warhol and Dylan didn’t come together through the gravitational force of fame alone. They were drawn together by something else — something markedly different from mass publicity. They were each part of New York scenes that mixed with and crisscrossed each other. Warhol reports in his book about the ‘60s, Popism (1980), that Dylan was on the scene. They ran into each other at parties and Dylan seems to have visited the Factory more than once. Dylan comments on Warhol (and Sedgwick) less elaborately than Warhol comments on him, but he does report that their paths crossed. From a Rolling Stone interview in 1985: “I don’t remember Edie that well. . . . She was around the Andy Warhol scene, and I drifted in and out of that scene.” In the Factory on that afternoon in 1965, Warhol and Dylan seem to have been brought together by Barbara Rubin, who appears in various Finkelstein photographs. Rubin collaborated with Warhol on several film projects in the mid-60s, and she turns up in a photograph on the back cover of Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home, released in March 1965, massaging Dylan’s head. Rubin is best remembered today for making one of the essential underground films of the early 1960s, Christmas on Earth (1963), and for energetically bringing together artists, poets, and filmmakers in the mid-60s for various collaborations. Also present (we know from Finkelstein’s photographs) was John Brockman, who, like Rubin, worked closely with Jonas Mekas, the genius impresario of New York underground film, and who, again like Rubin, had been involved in producing collaborations between artists, dancers, musicians, and filmmakers known as “expanded cinema” festivals. Dylan brought with him to the Factory (according to Finkelstein) his consigliere of the mid-60s, the painter and musician Bobby Neuwirth. The photographs also show that Warhol’s boyfriend of the time, the filmmaker Danny Williams, and his art assistant Gerard Malanga (also a poet) were present.

All this is to say that Dylan’s and Warhol’s scenes intersected in 1965 and early 1966. The participants in those scenes were often underground filmmakers (like Warhol himself at this time), and they were especially interested in multimedia art happenings. They created a moment in New York City’s cultural life where the barriers between various art forms seemed to be breaking down. They could imagine, one might suspect, some kind of collaboration between Dylan and Warhol, and perhaps they could even imagine a new kind of scene brought into being around that collaboration. Finkelstein’s photograph of Dylan, Warhol, and the Double Elvis begins to record an exchange — performed in certain ways more than it is put into words — that is principally about what happens when one’s scene goes mass. It captures a conversation about publicity and personas, affect and identification, even fear and creativity that shaped Warhol’s and Dylan’s art as they left their art-world scenes to become mass media stars, and it is a dialogue that continues into our own day.

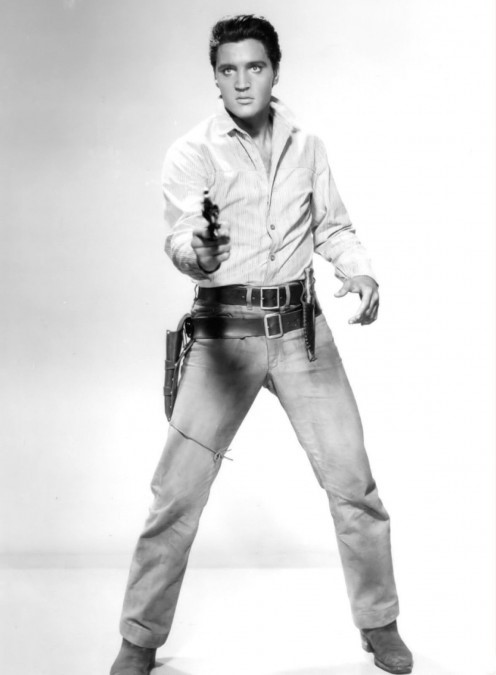

Dylan and Warhol stand together, framing the Double Elvis silkscreen that Dylan would later leave with. Indeed, Elvis looms up between them, outfitted as a cowboy and brandishing a revolver, as Warhol and Dylan speak to each other. Finkelstein reports that earlier in the day, before Dylan’s arrival, Warhol had disappeared into the Factory’s painting storage section to find an appropriate piece for the special visitor. The rock-star subject matter is obviously significant for its connections to Dylan, a just-minted rock star, but Warhol’s choice of an Elvis from film (the image is taken from a publicity shot for Elvis’s 1960 western Flaming Star) also must have resonated with Dylan,

Publicity shot for Flaming Star

who had filmed Dont Look Back in May 1965 and had aspirations, like Elvis, of working in mediums beyond music. In various senses, the Elvis silkscreen with its silvery background (this is difficult to see in Finkelstein’s black-and-white photograph) mirrored Dylan, articulating many of Dylan’s ur-themes in its depiction of the heroic and often solitary gun/guitar slinger crisscrossing the mythic West in the morality play which is the western genre. But Warhol converted these mythic values into something else even as he presents them in the Double Elvis. The Elvis in the silkscreen hardly convinces anyone he’s an actual cowboy — the clothes are too natty and neat, his pompadour too perfect. He’s clearly a construction, even a campy cowboy in a sort of drag. The portrait can’t help but emphasize Elvis himself as a kind of identity-switching appropriation artist (not unlike Warhol and Dylan) who made a career out of repackaging for mass consumption an array of local Southern scenes from juke joints to church choirs. Warhol also must have rather gleefully recognized the connection, if in title only, between the Hollywood vehicle Flaming Star and Flaming Creatures, the landmark underground queer film made by his friend Jack Smith in 1963 (in fact, the same summer as the Elvis painting) and starring an ensemble of drag queens and trannies. And who was Elvis anyway in 1965? To many he seemed done as an innovative artist, getting fatter with each bad movie (the comeback of ’68 virtually unimaginable). From one perspective, all of this suggests Warhol’s aggression towards Dylan: Dylan is a put-on, Warhol says with his offering of the painting — a piece of product, like Elvis, with no genuine, masculine agency. The manufactured image can be easily doubled (or tripled, as Warhol would do with Triple Elvis [1963], or nearly infinitely reproduced). But from another perspective Warhol’s conversion of the cowboy and the rock star, points of origin of American authenticity, into something fake is a perspective fully embraced by Dylan. As he reads about himself in a British newspaper in Dont Look Back, he cracks, “God, I’m glad I’m not me.” The acting — really, the method acting — defines Dylan, as does his appropriation of looks and lyrics. When he walks into the Factory, Dylan too is natty and neat like Elvis, wearing a fitted tan herringbone-stripe sports coat over a tucked black shirt and fancy black leather shoes. His electrified hair is just right. There’s even a hint of swish to him, in the dandified clothes and the way he holds his cigarette just so. He was no longer a scruffy folkie — the old act — or a Midwestern Jew, for that matter, whose identity could easily be read right off the arc of his nose. Dylan was pulling from some other, less familiar (at least to Americans) visible register than the mythic American West of cowboys and folkies — perhaps the urban flâneur rather than the Western rambler. From this perspective, Warhol had gotten Dylan just right. And it’s not clear that this exchange was done with bitchy antagonism either, for Warhol admired more than anything — if his portraits of Marylyn, Liz, Jackie, and, later in the early 1970s, New York drag queens are taken as evidence — the ways beauty, celebrity, and even identity itself could be put on like an act. He loved acts and acting, just like Dylan.

But ultimately what is most interesting about Finkelstein’s photograph may not be these knots of authenticity and artificiality, originality and appropriation, self and persona, history and self-conscious myth. What’s most interesting is Elvis’s face and body themselves. What is it there in Elvis’s eyes? Surprise? Concern? Warhol appropriates an image that catches Elvis reflexively responding or even defending himself (or at least acting so). The image emphasizes just how bodily this reflex is. Hence, the Double Elvis strikes an expression that hardly ever crosses the face or body of Warhol and Dylan. Do they even have bodies below their necks? Dylan buttons his shirt nearly to the top, as he still often does, and Warhol wears a long-sleeve black turtleneck. They are so often — here and throughout their careers — blanks before the camera’s lens. Sunglasses, seldom smiling, pale-faced with pursed lips — they share a look, not only in Finkelstein’s photographs but in most photographs from ’65 forward. Their eyes never display a hint of fear or surprise, but they are not exactly evasive either. They posed for the camera but never pandered to it. Alternatively, in almost all of Elvis’s TV appearances in the 1950s there is a brief moment when he walks on stage and flinches or starts. The response comes in reaction to the audience’s shrieks and screams, which must have hit like a sonic wave. Elvis’s momentary recoil reveals the star’s unease or at least surprise at becoming the focus of a mass public, a public that sees you in minutest detail but which you know only as an anonymous mass. Indeed, the mass public can see more of you than you can see of yourself. Meeting this gaze constitutes one of Dylan’s and Warhol’s most fundamental shared creations.

Both meet it with a dynamic mixture of personality and impersonality. When Dylan faces the booing, raucous audience at the Newport Folk Festival in July 1965, he doesn’t even blink. In the spotlight he looks like a leathered rock star playing to the camera, but he’s also stoned-faced, not unlike Warhol’s visages of Marilyn or Liz, who are immediately recognizable by a mass audience but impossible to fathom psychologically. In 1965 Dylan knew even at age 24 so much better than Elvis how the gaze of mass culture worked; he knew it perhaps better than anyone before him, with the exception of Warhol. By 1965 Warhol was responding to interview questions with only a yes or a no (earlier in his career he’d been much more chatty). In 1967 he famously sent an Andy Warhol double to speak for him at various universities in the American West. In Popism Warhol said of Dylan that the singer pulled off an “anti-act” — an act that paradoxically questioned the whole idea of acting — and the same might be said of Warhol himself. This construction of elaborate personas in league with a sphinx-like emotional and psychological blankness was surely both protective and subversive. Dylan and Warhol were not going to allow the public in, and they were not going to be disciplined by the mass. But their blankness was also productive. There were both deeply interested in how to communicate with a mass public, and they turned the mass gaze inside out, converting it from the knowing, disciplining, and containing to the creative. Dylan’s impersonality before the camera often produces a sense of deep and complex interiority, even an intimacy. The impenetrable surface begets fantasies of depth, but the look leaves you with only surface. It’s a classic Dylan characteristic, or ploy, or what-have-you. In its repetition, it turns into a brand.

In his two screen tests for Warhol, Dylan meets the camera’s aggressive stare with this face of impenetrability. It is beautiful and beguiling. For Warhol the screen tests themselves were a kind of experiment with the mass public’s gaze. These short films were silent, giving power to the image over the word. They required the sitter to stay confined in a frame of view the size of a chair, and often Warhol or another Factory operator turned on the camera and walked away, leaving the subject face-to-face with the apparatus mechanically ticking off frames as the film rolled for 100 feet or approximately four minutes. This could be a very strange experience. The screen tests viscerally recreate the violation of the mass, anonymous gaze (there was often no one even behind the camera), but from another perspective they offer sites for free play. Anything goes — there was no script, no direction, not even an artist. The form allowed anyone to become a work of art, to produce a work of art, to create a self before the camera. Warhol, for his part, took Dylan’s impenetrable visage, his anti-act, one step further, in a way. He made at least one screen test of himself, but it has disappeared from his archive, for the most part. What remains is a photograph of a strip of film three frames long. He’s there and not there.

The screen tests put in play the to and fro of personality and impersonality, surface and psychological depth, private self and public self, the presentation of self and the presentation of a brand, regulation and freedom before the mass gaze. These are, of course, among the antinomies of our age. Add to this list the others outlined above — authenticity and artificiality, originality and appropriation, self and persona, history and self-conscious myth — and an even fuller picture comes to light of the oppositions between which much of our contemporary experience moves. Dylan and Warhol never dissolve the oppositions they put in play. They move between them. Their power derives from the ability to hold the two poles in a state of suspension. They developed in the mid-1960s very similar personas in dialogue with these poles. Perhaps they learned those personas — absorbed them — from each other, and surely each persona nourished the other as they drifted in and out of each other’s scenes, becoming every day a more focused target of the mass gaze. Those personas were creative — ways of navigating a move from a life within a scene to one within a mass — but they must have also been driven by some degree of fear. There is at least a glint of fear in Elvis’s eyes, and that fear was justified by what the mass public could do to you. It’s the realization that the flip side of “fifteen minutes of fame” is the death drive — something that Warhol captures in his celebrity portraits, which are so often death portraits (as is the case with the suicide Marilyn and the widow Jackie). For the most part Dylan and Warhol continued to perform these personas for the remainder of their careers. But they also developed different responses to the dynamics they faced. Dylan at bottom is a moralist in ways that Warhol is not; Warhol, an ironist and perhaps even a pragmatist. But both bring the oppositions to the fore as a provocation to think about the world that circulates around such antinomies and the way people live in that world. To consider, most obviously, the possibility that selves are manufactured has the effect of challenging the typical notions of personhood which form the bedrock of many parts of our lives, personal and political. To raise the thought that impersonality or blankness before the mass gaze might produce a kind of intimacy has the effect of challenging our typical notions of how our fantasies work and to what exactly we make attachments, again both personally and politically.

Dylan and Warhol meeting at the Factory is a quieter moment than Dylan going electric or Warhol painting unadorned consumer staples. It doesn’t result in a great collaboration across mediums or begin any great narrative. It certainly doesn’t “split the sixties.” If anything, it is emblematic of the era after the ’60s were split — the post-sixties. We do all live in that era, one where authenticity, personality, depth, privacy, freedom, individuality, and a host of additional points of reference in our world are always entwined with their opposites and conversion between the poles is our daily creative practice.