Roots Moves II

Part 2 of an essay that begins here.

It is absolutely false to imagine that there is some providential mechanism by which what is best in any given period is transmitted to the memory of posterity. By the very nature of things, it is false greatness which is transmitted. There is, indeed, a providential mechanism, but it only works in such a way as to mix a little genuine greatness with a lot of spurious greatness; leaving us to pick out which is which. Without it we should be lost.—Simone Weil, “The Need for Roots”

Arnold Weinstein: The Magical Use Of Language

Arnold and I were talking about the modern world. He thought a moment and then said, “History is a thing of the past.” The comedic surface of that remark, coupled with its profound undertones, was typical of his extraordinary mind.

Migration Suite

Ida Mae Brandon Gladney, Van Fleet Mississippi 1928

(After Isabel Wilkerson)

ida mae’s most memorable toys were

water moccasins

she dangled them

from the tips of sticks tossed the snakes

into the air & caught them (on the sticks

not in her hands)

Pimpology

True story # 1: It’s a late spring Thursday in New York City in the late ‘70s and I’m a kid in high school. For reason I can’t recall, the entire student body was dismissed at noon. A halfaday!

Free! What to do? What to do? My pal Joel has an idea. He opens his copy of the New York Post–yes, we read newspapers back then–to the movie section and points to a small ad. It’s the final day of Pam Grier film festival at the RKO Warner in Times Square. Yes, indeedy, five, count ‘em, five of her finest efforts–Coffy, Foxy Brown, Bucktown, Sheba Baby and Friday Foster–for the price of one three dollar ticket.

The Chilean Road to Hell And/Or Socialism: A Nihilistic Workers’ Inquiry (Part 2)

Part 2 of an essay that begins here.

5.1. Health and Its Discontents

Some of my best friends, and I’m talking about people in their twenties or early thirties, the ones with truly radical and self-sacrificing souls, have been so terminally unhealthy and non-athletic, or anti-athletic, that in the rare moments that we end up playing a sport, they invariably fall ill, they turn red or purple, they vomit and they take to bed for days.

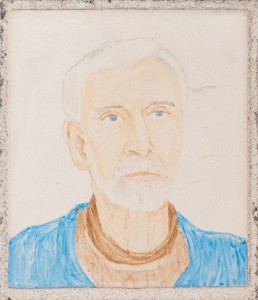

Edwin Denby

George Schneeman, Edwin Denby, 1977, fresco on cinder block. Private Collection, New York

Once when we were having lunch at the Oyster Bar in Grand Central Station, I complained to Edwin about hearing myself on a tape of some recent poetry reading. “Yes,” Edwin said matter-of-factly in his customarily soft, slightly gravelly voice, “that resentment tone.” Thinking back on it over the years, I may not have understood the intriguingly commiserating aspect of Edwin’s remark.

Roots Moves

“Loss of the past, whether it be collectively or individually, is the supreme human tragedy, and we have thrown ours away just like a child picking off the petals of a rose… We owe our respect to a collectivity, of whatever kind—country, family or any other—not for itself, but because it is food for a certain number of human souls.”—Simone Weil, “The Need for Roots”

Simone Weil once lived in a building around the corner from Tiemann Place in West Harlem where we held our 29th annual “Anti-Gentrification Street Fair” in October.

Jihadism vs. Humanism

Film director Abderrahmane Sissako, best known for Timbuktu, his film about the Islamist occupation of that historic city, spoke about his life and work in a dialogue with film scholar Michael Cramer at the French Consulate in New York City last week. His comments on the vicious killjoys who meant to humiliate Africans in Timbuktu by forbidding music, sports, and irreverence have taken on a new resonance in the wake of the terror attacks in Paris. But Sissako’s presence would be bracing at any time. Click on his picture below to see/hear video of the event at the French Consulate. Be aware it runs on empty for a couple minutes before you begin to hear crowd noise. The conversation starts about 1o minutes in. (And before you go there, you might want to check this memorable scene from Timbuktu, which was also shown about an hour into the discourse at the Consulate.)

Sissako noted he hoped Timbuktu would uphold the humanism of those in that city “who resisted silently”: “Those who hid to sing, or listened to the radio under the blanket, or were playing soccer in their minds.” He averred he lacked such quiet courage, but his modest, yet undeniable acts of imagination make one doubt his self-assessment. What seems most likely is that Sissako’s characters are true to their director’s beautiful core. You’ll catch a glimpse of it, if you watch the conversation above.

Thanks to Judith Walker, Mathieu Fournet and Cultural Services of the French Embassy for enabling First to embed their video (and to Oliver Conant for steering your editor to the event last week). B.D.

They’d Rather Be in Philadelphia

Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun observed that “if a man were permitted to make all the ballads he need not care who should make the laws”. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton is now testing an expansion of this proposition: if you could make all the ballads, need you care what is taught in the schools?

Timothy Mayer’s “Adams Chronicles”

Fredric Smoler’s mockery (above) of wannabe worldly—truly deadly—approaches to the American Revolution has an extra kick for this editor. My son’s assigned reading in his 7th grade class this season is a Y.A. text, My Brother Sam Is Dead, that leeches glory—and all the juice—out of our country’s creation story. Higher learning’s disdain for “American exceptionalism” seems to have trickled down to progressive high schools and middle schools.

“Hamilton”

In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes, “In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body – it is heritage.” The United States has brutalized not only the black body but the indigenous body, simultaneously denying these people, along with women and non-Anglo immigrants and their descendants, the full rights of citizenship. Since the late 1960s, it has been commonplace for the arts to highlight American hypocrisy. And so, hearing, in the age of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, of a hip-hop musical about the American Revolution and the early days of the Republic, written by and starring a Latino-American with African American actors playing most of the second leads, one might reasonably assume that such a play would drip with irony. One might anticipate raps about the three-fifths clause and property requirements for voting, eleven o’clock numbers by displaced Shawnee, and choruses sung by Sally Hemmings’ children. One would be wrong.

Caravaggio (Redux)

One night in bed you asked me who was my favourite painter. I hesitated, searching for the least knowing, most truthful answer. Caravaggio. My own reply surprised me. There are nobler painters and painters of greater breadth of vision. There are painters I admire more and who are more admirable. But there is none, so it seems—for the answer came unpremeditated—to whom I feel closer.

Greider and Goodwyn

William Greider published a piece last week criticizing a New Yorker “Talk of the Town” take on Trump (and Bernie Sanders) that conflated their political theater with American populism. Greider emailed a link to his Nation piece, which he self-deprecatingly described as a “rant,” to me (and others). I responded as follows…

Is Dan Mad?

George Trow’s magnificent, prophetic piece on Dan Rather—first published in First of the Month in 1999—never grows old.

Square Dance With God

The author is a physician and priest who has been working in Haiti for more than a generation, running hospitals and social programs in Port au Prince as well as a Nuestros Pequenos Hermanos (NPH) orphanage on the outskirts of the capital. Fr. Frechette is the author of The God of Rough Places, the Lord of Burnt Men and First has often posted his stories from Haiti.

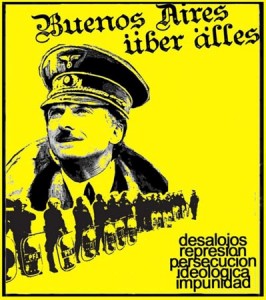

The Other 9/11

On September 11th, every year, it became a habit for certain melancholic leftists who consider themselves heretical thinkers to reflect, not on the Ouroboros of McEmpire and McJihad, or whatever, but on Allende shooting it out with fascist generals with Castro’s sub-machine gun.

The African Lady (Redux)

When Ta-Nehisi Coates was trying to make sense of the world as a young student, his first working theory “held all black people as kings in exile, a nation of original men severed from our original names and our majestic Nubian culture.” With help from teachers at Howard, Coates thought his way out of compensatory history. Coates’s movement of mind sent your editor back to the following post by Anita Franklin, which originally appeared here in 2013. B.D.

Very Serious Fantasts

P.W. Singer and August Cole have just published Ghost Fleet: A Novel of the Next World War.