In my dreams, I was constantly losing my brother in the midst of World War III. In despair, I didn’t want to go on, but I’d go on. I’d see him then as he was as a kid of four or five. His sweetness got him killed. Whereas I, even at my worst and most lost, always had an instinct for reality. I’d felt from an early age appointed or called by something. But reality was a minefield, starting with my own somatic experience (failure to be held). Something, some threat in the biological or social world, was always poised to interrupt where I was meant to go (K’s theory early in our friendship about Spinoza, Proust, imperial time, and death, and years later when he told me about what Grace Lee said about James Boggs, how she’d never met a person who could sleep so soundly, the kind of sleep that comes from being a Black man born in Alabama who lives and breathes a revolutionary humanity).

Hunt and Pecker

From the department of don’t stand near me because I’m vomiting. In the current New Yorker, from a profile of Wendell Berry by Dorothy Wickenden, subtitled, “Wendell Berry renounced modernity sixty years ago, but his ideas have never been more pressing.”

Coming Out is Going Home

As much as I like to fancy myself an expert in all things basketball — among the sport’s cognoscenti — there are lacunae, areas of ignorance my son made me aware of as he morphed from being my (forgive me) beautifully instructed phenom into a college player, and I receded into the ranks of high school assistant coaches.

Putin (with Stooge) vs. Navalny

Since I haven't found an English version online, I've added subtitles to Putin's humiliation of his spy chief during today's grotesque security council meeting in the Kremlin. pic.twitter.com/bFx25nWzTK

— Peter Liakhov (@peterliakhov) February 21, 2022

Nightmare Scenarios and Beamish Projections

Linguistics Professor and author John McWhorter (McW hereafter) is many things. He is an elegant and effective writer and perhaps an even better talker. Moreover, he knows his way around an argument and is often on the right side of one. And not least of all, he can be wickedly funny as anyone who has seen him on cable TV harpooning Donald Trump and others surely knows.

These days though, he is increasingly a man on a mission. In Woke Racism (2021), his recent crusade (sadly, it is hard to term it anything else) against those who would sound the alarm about the continuing impacts of racism in America, even at his best, he fails to put his points about the excesses of “Anti-Racism”—many of which are spot on—into the broader context of all that ails us today. At worst, e.g., when branding what he calls “Third Wave Anti-Racists”—like prominent authors Ibram Kendi and Ta-Nehesi Coates—as “high ‘priests’ in an ‘ideological reign of terror’” and “gruesomely close to Hitler’s racial notions in their conception of an alien, blood-deep malevolent ‘whiteness’”—he has, I fear, gone off the rails.

McWhorter’s Rare Dare

The second and third volumes of Stoppard’s trilogy on 19th C. Russian revolutionaries, The Coast of Utopia, is mostly set in exile, but Voyage, the first volume, is set in Russia. A brilliant speech opens its second act: Alexander Herzen, appearing for the first time, addresses the audience, explaining both a children’s game and picture book titled ”What is wrong with this picture?” and the situation of Russia under Nicholas I. Herzen gives some examples of what is horrifically wrong under Nicholas’s autocracy, and concludes “Something is wrong with this picture. Are you listening? You are in the picture.” It is the most theatrically brilliant moment in the trilogy. Herzen suggests that we do not seem to take in the grotesquerie of what is happening, or are perhaps merely afraid to speak of it. I think he is also implying that whichever is the case, in not noticing what is supremely visible and in not speaking about what is clearly outrageous we are to a degree complicit in such things, also more vulnerable to them happening to us.

This is pretty much John McWhorter’s strategy in Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America.

Ashes (& Fetishes)

..The ultraleft poets, former readers of Tiqqun (turned towards moralism, though occasionally they would still say liberals, put a bullet in your head), were bitching about a cringe and morbid poem written by a Seattle doctor about his “friend” the maintenance man, his “friend” Juan, dead of Covid on the couch before he was even fifty: a necropolitical dirge for the working class, a poem written to bury, not to praise, the working class, etc. The good doctor knew enough to ask what right have I to write this poem? But this only infuriated the ultraleft poets more. As did the admittedly offensive and aesthetically appalling image contained in the line I who will not see him in his uniform of ashes (the doctor must have thought he was channeling Paul Celan), which made me wonder if the doctor thought janitors are buried in their uniforms, condemned to the pyre in their subordinate social role. The ultraleft poets were not happy with this poem. They asked when one has the right, ethically, to mourn, in a poem, another over whom one holds power in a hierarchical relationship. I thought it must be tiring to live this way, to create art this way.

In Praise of Secular Jewish American Lyric Commentary: Why Bob Dylan and Louise Glück are 21st Century Nobel Laureates

Seven decades after what Benjamin Schreier calls, “the dominant event of Jewish American literary history,” which is the “‘breakthrough’ – the irruption in the 1950s of Jewish American writers like Bernard Malamud, Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, and Grace Paley into the heart of American cultural scene,” two Jewish American lyricists have received the Nobel Prize for Literature in a span of four years: Bob Dylan (born Robert Allen Zimmerman in Duluth, Minnesota in 1941) in 2016 and Louise Glück (born in New York City in 1943 and raised on Long Island) in 2020 (Schreier, 2).

Way Down Yonder

On November 22, 1963, Lee Harvey Oswald, an ex-Marine of skittish enough character to have defected both to and from the Soviet Union, was arrested for assassinating John F. Kennedy by firing three shots from the Texas Book Depository building in Dallas, Texas, as the president rode in a motorcade below. Two days later, Jack Ruby, a local nightclub owner, killed Oswald. A commission, appointed by President Lyndon Johnson and chaired by Chief Justice Earl Warren, concluded Oswald a solo act. This conclusion launched a thousand books, several films, and not a few careers selling counter-theories as to who the actual perps – CIA, FBI, Mossad, Mafia, a military-industrial consort, pro-and anti-Castro Cubans – had been and what role, if any, Oswald and Ruby played.

Character of the Assassin

The author wrote this right after JFK’s assassination, finishing it on the day Lee Harvey Oswald was murdered by Jack Ruby. It was published in The New York Review of Books and in the essay collection, You Don’t Say (1966).

Moaning Pitched High Enough Sounds Like Laughing (An Excerpt from “Working at it in Five Parts”)

My favorite thing is laughing so hard I have to lower myself on the wall to the floor to keep from falling down. I come from a family of gifted laughers. My brother Walter has an explosive, knee bent, leaning backward with hand over the heart, blow the house down laugh. It’s a rumbling that comes up from below, ricochets off the rib cage, pole vaults into falsetto that lifts him up on his toes, opens the sluices. And it’s water works for days. My daughter Karma as a little kid would complain, her palms like ear muffs, “Uncle Walter hurts my ears.” With an interruption of that sort, Walt emits a ahhhh-that-was-funny sigh. Then remembering how funny, he’s off again. Walt had a great teacher, our father.

Shadows: John Thompson’s Reckoning with Race

“BIG JOHN… BIG BAD JOHN” – Song lyric from my adolescence (that has escaped Google’s dragnet).

Former Georgetown basketball coach John Thompson’s autobiographical account of his life and times I Came As A Shadow, written along with Jesse Washington, and completed just before Thompson’s death in 2020 at the age of 78 (2020), is a passionate, but sober paean to his parents’ teachings and love.

Rocky Mountain High

What easier target than John Denver, Henry John Deutschendorf Jr., Aspen’s poet laureate, that insipid 70s fauxkie whom if you turned on the radio you could not at the time avoid being made to hear or block from your sight on TV whether you tuned into the Grammys or the Muppets (and I know this, I was there), who would be singing about sunshine on his shoulders or being taken home along a country road, his senses filled up by his loving wife Annie (herself little more than a vehicle for the nature images Denver would summon to describe her, a night in a forest, a walk in the rain, a storm in the desert, a sleepy blue ocean—one heck of a relationship I guess), his “Rocky Mountain highs” presumably purer than Joe Walsh’s “Rocky Mountain Way,” spiritual elevations delivered through nature’s bounty and domestic bliss, Ralph Waldo Emerson by way of Werner Erhard, but who we always suspected to be and later learned was (in part from Denver’s own autobiography, called what else Take Me Home) a celebrity stoner and cokehead (not that there’s anything wrong with that) who at one point in a mid-divorce rage chainsawed his beloved Annie’s bed in half. Easy peasy, a little cultural studies, a little Hollywood Babylon, done and dusted. I think there are other reasons as well why the above story is too easy.

Time and Skyline in Scorsese’s Stoic Epic

Framing the battle

The long narrative core of Martin Scorsese’s 166-minute epic Gangs of New York (2002) is bracketed by two highly stylized sequences — the first, a dystopian “once upon a time” inside a huge ill-lighted building, and the second, a cinematic dissolution of time in a Brooklyn cemetery.

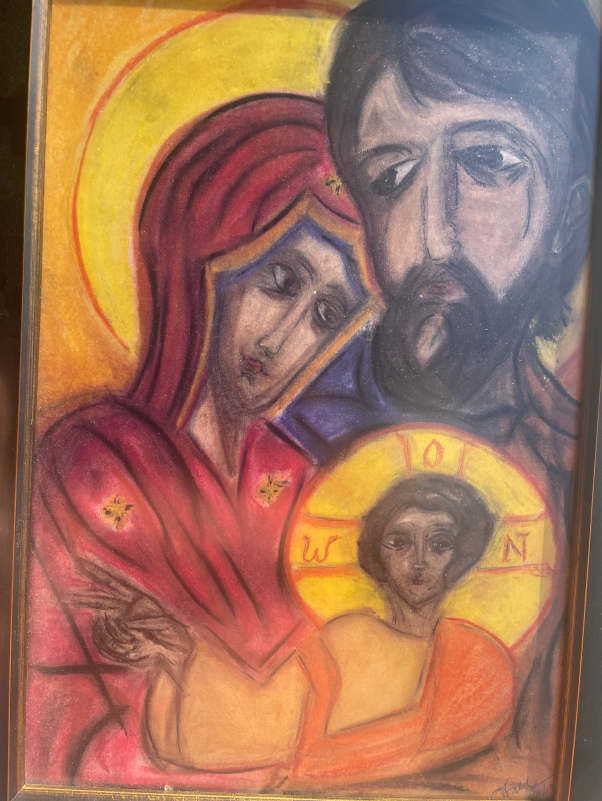

Epiphany, and the Flight into Egypt

While quietly crossing the threshold from a most difficult year into a (hopefully) better year, I lit a simple fire in an old tire rim, and with Orion twinkling in the darkness above, I contemplated the religious icon that accompanies these words.

Grace and Gravity

Klay Day.

The Myth of Joan Didion

Joan Didion’s death last week was followed by an outpouring of praise stretching over a week in The New York Times. This raises a critical question. Was Didion really a great writer, or merely the vector of attitudes held by the commenting class? The answer lies not just in her most famous books and essays, but in a piece she wrote that has been overlooked by those who present her as a seer into the enduring meaning of the past.

Didion has been cast as a prophet of the present who “told the truth about America,” as one Times writer gushed. Well, she did tell a kind of truth, one that many sophisticated readers wanted to hear after the traumas of the 60s. Apparently, they still want to hear it. Her images of crazed violence resonate, for her admirers, with the current threat posed by the violent right. But this selective view of Didion’s work ignores the evidence that her dystopian gaze was usually a reactionary one.

Robert Silvers’ Legacy (& “The Fiery Lieutenant”) (Redux)

This essay on Robert Silvers–first posted here in 2017–ends with an invocation of Joan Didion’s essay on the Central Park Five. For that reason and others your editor has lifted it out of the archives to pair with Richard Goldstein’s No-in-Thunder to hagiographic responses to Didion’s passing…

Farewell Tour

I caught the 9:15 morning flight from JFK to Burbank, California. The purpose of this trip was to visit a place where a great friend had died and to see other old friends who were under attack by Cancer and age-related conurbations. I anticipated a grim but necessary experience. Since I’d begun to accept the notion of my own mortality, I wanted to know how old friends were facing the end of the line.