This is the way CNN commemorated Memorial Day in 2015, with a story they called, “The General Who Apologized to the Dead Soldiers on Memorial Day.”

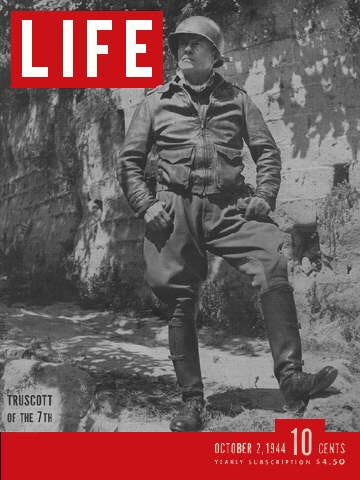

“At the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery at Nettuno, Italy, Memorial Day 1945 was an elegiac occasion. Lt. Gen. Lucian Truscott Jr., who had led the U. S. Sixth Corps through some of the heaviest fighting in Italy and now commanded the Fifth Army, gave a speech that is particularly relevant for today when the trauma of our long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan continues to haunt so many vets.

No recording or transcript of Truscott’s Memorial Day speech exists, even among his papers at the George C. Marshall Research Library in Virginia.

In Stars and Stripes, the military’s newspaper, we have only excerpts of Truscott’s remarks. “All over the world our soldiers sleep beneath the crosses,” Stars and Stripes reported Truscott observing. “It is a challenge to us – all allied nations– to ensure that they do not and have not died in vain.”

Missing from the Stars and Stripes story is what Truscott did in delivering his speech. For that account we are indebted to Bill Mauldin, best known for his World War II cartoons featuring the unshaven infantrymen, Willie and Joe. Mauldin was in the audience when Truscott spoke at Nettuno, and he never forgot the day.

“There were about twenty thousand American graves. Families hadn’t started digging up the bodies and bringing them home,” Mauldin recalled years later in his 1971 memoir, The Brass Ring.

“Before the stand were spectator benches, with a number of camp chairs down front for VIPs, including several members of the Senate Armed Services Committee. When Truscott spoke he turned away from the visitors and addressed himself to the corpses he had commanded here. It was the most moving gesture I ever saw. It came from a hard-boiled old man who was incapable of planned dramatics,” Mauldin wrote.

“The general’s remarks were brief and extemporaneous. He apologized to the dead men for their presence here. He said everybody tells leaders it is not their fault that men get killed in war, but that every leader knows in his heart this is not altogether true.

“He said he hoped anybody here through any mistake of his would forgive him, but he realized that was asking a hell of a lot under the circumstances. . . . he would not speak about the glorious dead because he didn’t see much glory in getting killed if you were in your late teens or early twenties. He promised that if in the future he ran into anybody, especially old men, who thought death in battle was glorious, he would straighten them out. He said he thought that was the least he could do.”

Grandpa was a hard man. He was born in Chatfield, Texas, in 1895 and never completed the 10th grade, and at age 16 took over the teaching duties in a one room schoolhouse in Enid, Oklahoma when the teacher died, completing the instruction of the students two years later. He enlisted in the Army and joined the Cavalry, serving at several Cavalry outposts along the borders of Texas and Arizona. He became an officer, a Second Lieutenant, because of his skill at playing polo. One of his commanders wanted Grandpa on his polo team, and he sent him to officer candidate school because only officers played polo in the Army in those days. He rose quickly to the rank of captain at Fort Bliss, Texas, because the post commander wanted Grandpa to captain his polo team in a championship match against a rival general at Fort Riley, Kansas, and you had to have the rank of Captain to captain an Army polo team.

Grandpa was hand-picked by the Chief of Staff of the Army, General George C. Marshall, to go to England before the U.S. became formally involved in the war. He also sent Grandpa there to get to know the British military commanders and report back to him about their personalities, competence as leaders, and anything else he could pick up in the way of intelligence on the allies Marshall knew the U.S. Army would soon be fighting alongside. While in Great Britain, Grandpa formed and was responsible for naming the Army Rangers, and arranged with Lord Louis Mountbatten, chief of combined operations for the British Commandos, to have the Rangers trained alongside British commandos at a base in Northern Ireland. Major William O. Darby, who became famous as the commander of “Darby’s Rangers,” was his deputy.

Marshall gave Grandpa his first combat command, of the Sixth Regimental Combat Regiment, at the landing of U.S. forces on the continent of Africa at Port Lyautey, French Morocco. He went on from there to command the Third Infantry Division in the battles for Sicily and Southern Italy. He took over command of the Sixth Corps at Anzio, and was in command when the U.S. Army took Rome. He took command of the Seventh Army and led the invasion of Southwest France with the landing in Marseille and took that army all the way to Strasbourg before being sent back to Italy to command the Fifth Army. He took the surrender of the Nazi army commanded by Field Marshal Albert Kesselring on April 29, 1945, the first unconditional surrender of enemy forces in World War II.

At the end of war, after several antisemitic outbursts by General George S. Patton were reported in U.S. newspapers, General Dwight D. Eisenhower relieved Patton of command of the Third Army and turned command over to Grandpa, appointing him Military Governor of Bavaria and putting him in charge of all the Displaced Person camps in Southern Germany. Under Patton, Jewish survivors of the Holocaust were being kept in camps in conditions not much better than they suffered in the Nazi concentration camps. Grandpa moved the Jewish survivors into housing at German army posts he seized and arranged for a dozen Army Rabbis to be sent to Bavaria to serve the survivors. Grandpa ordered that the first Seder in over a decade be held in Munich in April of 1946, and ordered that “A Survivors Haggadah” be printed by the Third Army for the occasion. This is its cover:

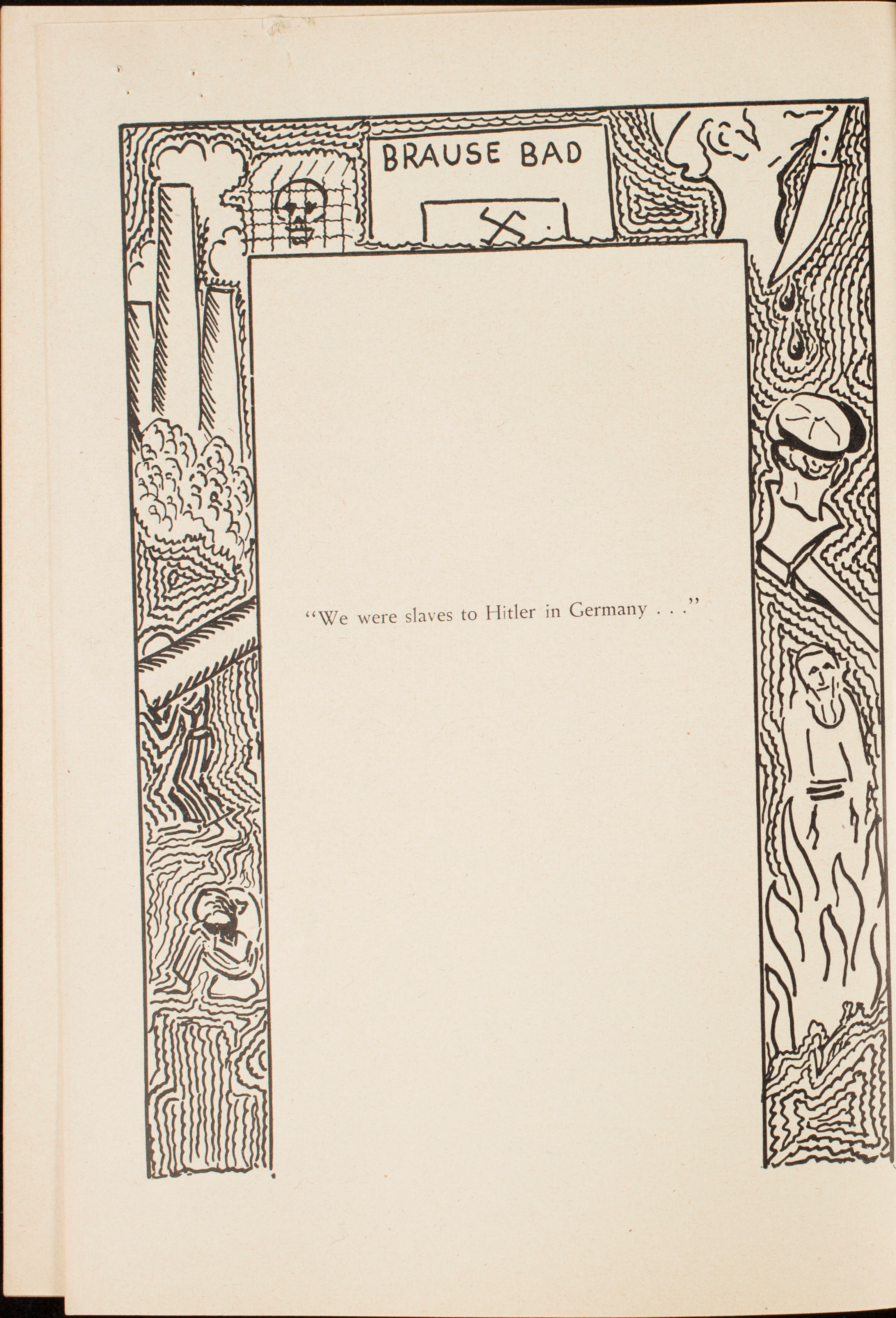

This is the first page of “The Survivors Haggadah,” another kind of memorial to the dead of another kind of war that was waged by the Nazis against Jews before and during World War II:

“The Survivors Haggadah” was illustrated by woodcuts made by a survivor of the Dachau concentration camp outside of Munich. As commander of the Third Army, Grandpa held the war crimes trails in Munich for the guards and commanders of Dachau and executed many of them.

I knew Grandpa growing up as a boy and spent several summers with him and Grandma, Sara Randolph Truscott, at their home in Northern Virginia. I don’t recall seeing Grandpa smile much when I was a boy. The war, and what he did as a commander of U.S. soldiers, and what he saw during and after the war, left him a broken man. The only time he ever said anything about the war was to my father on the night before he shipped out to serve in the Korean War. They were standing at night after supper along a fence behind a farmhouse Grandpa had bought for his retirement in Loudon County, Virginia. Dad asked Grandpa what advice he could give him before he went to war. Dad told me it was the only time in his life he ever saw his father cry. Dad said that Grandpa began sobbing so hard, he had to lean with his arms over the fence in order to remain standing. Every Memorial Day, I remember his words to my father that night: “The bodies, the bodies, all those dead boys, the bodies…”