I was born in 1946 into a pacifist Anabaptist milieu, strong on community, social justice, congregational singing, and what I remember now as thoughtful piety, striving to live by the Sermon on the Mount, uncomfortable with displays of emotional intensity.

We watched Elvis Presley on TV when I was ten, but Pat Boone, Presley’s biggest competition on the 1950s pop charts, was my favorite because I knew Pat was a Christian. So I was astonished when my older brother bought an Elvis record that included “Peace In The Valley” and “Precious Lord.” Something personal, even physical was happening in those songs that I couldn’t explain and it wasn’t happening with Pat Boone, or on my Sunday mornings.

Turned off by the watered-down affluent white suburban Christianity around me during my teenage years, I escaped into the secularized world of 1960s political protest, counter-culture, and pop music. In my early twenties, Motown, Stax, the Beatles, Stones, Aretha, Dylan all nourished me with something I wasn’t getting in church. In fact, it was while listening to WCFL Top 40 radio in my room in Chicago that I had my one and only shocking spiritual revelation.

The Beach Boys came on – and as I wrote in my book Why The Beach Boys Matter – physical chills ran up and down my body and I knew: this music was, more than any other, mine. Or maybe really, that this music was me. I don’t think I even heard an entire song. It was just a phrase or maybe a wordless stretch of vocal harmony, and that instantaneous comprehension.

I was disappointed. If this was going to be my big revelation couldn’t it have been about a bigger topic? And if it had to be about music, couldn’t it have been about something a bit, well, hipper or profound? I was living on the Southside, the giants of Chicago Blues like Muddy Waters were still in their prime. Jazz innovators Joseph Jarman and Roscoe Mitchell and all who formed the Art Ensemble of Chicago were creating ground-breaking music. And I got short-changed with a revelation about The Beach Boys.

Nonetheless, that was the revelation I had been given, so I pondered and pursued it.

In 1967 I moved to the East Village in New York and was lucky enough to live down the block from one of the places rock criticism was being invented. I didn’t have the stamina or chops to make a living writing about music, but through my friendships in that world I got occasional opportunities. In 1972 Creem magazine published my two part “The Beach Boys – A Fan Tells All.” In 1976 I wrote the chapter on Disco for The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock ‘n’ Roll. And in 1978 I was invited to contribute to Stranded, an anthology of essays about the one album a rock critic would choose if stranded on a desert island.

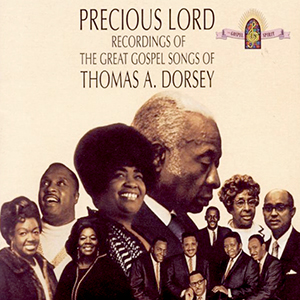

I chose a record I owned but had never listened to: Precious Lord, Recordings of the Great Gospel Songs of Thomas A. Dorsey. In the late 1970s most white rock critics and fans were aware of Rock’s debt to the Blues, but less knowledgeable about Rock’s debt to African-American Gospel. Writing about Precious Lordwould give me a chance to educate myself about bluesman Georgia Tom who became Gospel pioneer Thomas A. Dorsey, “our Irving Berlin”, as Mahalia Jackson described him, whose classic compositions included those two Elvis songs that puzzled me as a child. It was 1978, the activism of the 1960s was receding (or being driven) into the past. I began my essay with a quote from African-American theologian James Cone that ended: “Thus they [black slaves] found it necessary to develop a style of freedom that included but did not depend on historical possibilities.”

I believed that white fans and writers all too easily projected their own needs and misconceptions onto Black music without understanding the social context, so when a friend at work told me she was singing as the opening act for a concert of Gospel acts at her church in Harlem, my wife and I made sure to attend. The evening was so welcoming and inspiring that we went to other similar concerts in African-American churches in Manhattan and Brooklyn, touched by singers like The Mighty Clouds of Joy, The Keynotes, and Dorothy Love Coates.

These experiences were so transformative that I decided I wanted to start going to church again, but it would have to be someplace convenient that accepted my interfaith family, my gay friends, did not demonize my atheist friends, and had a gospel choir. I needed an inclusive welcoming congregation but I also needed that spiritual ka-pow I absorbed in those gospel concerts. Our friends Jack and Yvonne on 3rd Street listened to my list of impossible demands and suggested “that church on 7th Street.” And that’s how I walked in the door at Middle.

After my first service I realized there had been an additional unconscious demand: that the church have a regular choir that wasn’t pathetic. I’d passed through congregations with theologies I liked whose woebegone choirs telegraphed emotional starvation and a shaky future. I wasn’t expecting The Fillmore East or The Apollo on a Sunday morning, but I was expecting some intensity.

So there I was. Gordon Dragt was in the pulpit, Jerriese had started the Gospel choir, Jonathan was leading the already excellent “regular” choir, and I’ve been at Middle ever since. Over the years I’ve sat in the pews thinking about Pentecost, and speaking in tongues, and Pentecostalism and its influence on rock ‘n’ roll. I’ve thought about the connections between pop concerts and worship services. I’ve thought about religious intolerance and emotional intensity and how to keep them separated, about individual disintegration and being seized and restored by the spirit. And sometimes I’ve thought about the quiet piety I was exposed to as a child.

When I got the chance to write my book about the Beach Boys two years ago one last piece of a puzzle fell into place. I knew the Beach Boys, like all white sixties pop acts, owed an obvious debt to Little Richard and Chuck Berry. I knew a lot of their version of rock ecstasy reworked long musical traditions from out of the African-American church. But when I thought about it, after all those years at Middle, I realized that the Beach Boys had combined those rock elements with a spirituality often expressed in vocal harmonies that traced back to Doo Wop of course, but also to mid-century Euro-American church music. That unacknowledged, unconscious synergy of diverse white and Black American spiritualities, consciously entwined every Sunday at Middle, was hidden inside my original revelation about the Beach Boys, and spoke to my own personal splits and connections, and it took those years worshipping at the church on 7th Street to unlock all that. I had to understand and meet my own spiritual requirements before I could locate them inside the music of the Beach Boys. When I did, it deepened my appreciation of my favorite pop music group.

When I got the chance to write my book about the Beach Boys two years ago one last piece of a puzzle fell into place. I knew the Beach Boys, like all white sixties pop acts, owed an obvious debt to Little Richard and Chuck Berry. I knew a lot of their version of rock ecstasy reworked long musical traditions from out of the African-American church. But when I thought about it, after all those years at Middle, I realized that the Beach Boys had combined those rock elements with a spirituality often expressed in vocal harmonies that traced back to Doo Wop of course, but also to mid-century Euro-American church music. That unacknowledged, unconscious synergy of diverse white and Black American spiritualities, consciously entwined every Sunday at Middle, was hidden inside my original revelation about the Beach Boys, and spoke to my own personal splits and connections, and it took those years worshipping at the church on 7th Street to unlock all that. I had to understand and meet my own spiritual requirements before I could locate them inside the music of the Beach Boys. When I did, it deepened my appreciation of my favorite pop music group.

xxx

Reprinted from Sunday, A Magaizne of the Arts At Middle Church. Special thanks to Carol Wierzbicki for her encouragement, and to everyone at Middle for making it happen.