Merle Haggard was probably the greatest singer-songwriter I’ve ever seen. The only artist I can think to compare him to is Sam Cooke, who like Merle possessed the gift for writing songs that were at once both deeply personal and universally applicable to the human condition.

Merle Haggard was probably the greatest singer-songwriter I’ve ever seen. The only artist I can think to compare him to is Sam Cooke, who like Merle possessed the gift for writing songs that were at once both deeply personal and universally applicable to the human condition.

Merle’s were a lot more mournful, it’s true (think “If We Make It Through December,” “Things Aren’t Funny Any More,” “I Can’t Be Myself When I’m With You” – not to mention “Mama’s Hungry Eyes”) – but they were no less expressive of the kind of unnameable yearning that none of us can escape, and no less eloquent in their empathy for people from all walks of life, the ability to bring to life circumstances and events that only in their emotional impact (but totally in their emotional impact) resemble the singer’s own.

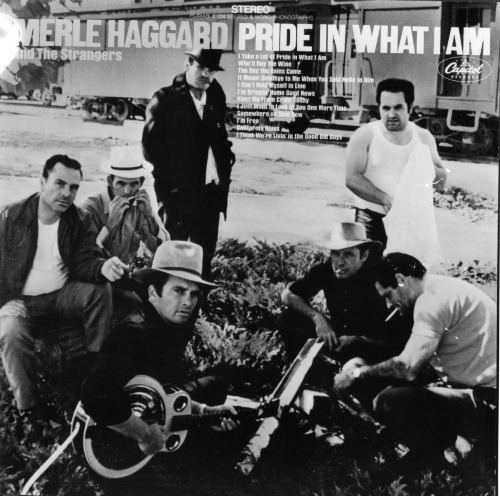

Like Sam Cooke, too, he possessed a voice unmatched in its expressiveness, its seemingly effortless conveyance of nuance not only in his own music but in his brilliant interpretations of others, particularly two of his greatest heroes, Jimmie Rodgers and Bob Wills. His impeccable musicianship, the extraordinary band that he assembled and added to over the years (what else could they be called but the Strangers) ensured that he was able to present his music the only way he could conceive of it, just as he heard it in his head. When I first met him in 1978, he told me he was about to publish a book of poems called A Poet of the Common Man (don’t look for it, it never came out – but I’ll bet it would have been great), along with two novels he was working on, one of which he said would be a comedy-mystery. He was a man of limitless imagination, someone who found order in his art, and yet at the same time he seemed not only to thrive on, but to create, chaos all around him. (“You know, I’m a strange kind of person,” he told me, “the more that’s going on, the more life I’m able to be involved with and learn about, the more it seems to replenish my well of ideas.”)

I guess that would be one way of looking at it – but Merle was a man beset by demons that he couldn’t always control, publicly or privately. I remember one time seeing him play for an auditorium full of people who kept cheering him wildly, even as they could barely hear his voice coming out of the PA system. Any number of technical fixes were proposed, both from the audience and onstage, but it soon became evident that Merle simply didn’t feel like performing that night (this was not the only night I saw this happen), as he stood at a disdainful distance from the mike and the soundman kept raising the the sound level until the feedback became almost painful. A couple of times he would move in a little closer and say, “Is that any better?” as the crowd yelled enthusiastic encouragement – but then he just stepped away again.

You got the feeling that he was mocking both the audience and himself, as he responded to a request for “Okie From Muskogee,” perhaps his most famous song, a call for a return to a mythic past in which Merle himself could never have lived (it depicted a land where no marijuana was smoked, “and the kids all respect the college dean”), whose origins as a goof on middle-American political correctness, would immediately become apparent to anyone who ever set foot on Merle’s bus. It didn’t matter: the audience continued to cheer lustily, and Merle continued to look thoroughly disgusted with himself, like a man trapped in a world he had never meant to make. Just for the record: Merle canceled the rest of the tour the next night.

But then there were the nights on which his face was wreathed in smiles, when he was carried away by the music and would spend as much time encouraging his fellow musicians to surpass themselves as he did claiming the spotlight for himself – in fact, the spotlight never entered into it at all. That was what you heard on the best of his songs, the most inspired of his recordings, where even Merle’s black moods were transmuted into a tender regard for all the multifarious sources of his inspiration, all the diverse people and places his imagination was able to take him to. There – in the songs – he seemed able to set aside all of the insecurity, all of the anger, all of the looming fears and resentments, and place them at the service of his art.

He liked to talk about the songwriting sometimes, about the role that art played in his life (check out the enhanced eBook edition of Lost Highway for an insightful meditation on the range and ambition of his writing). He always made the distinction between formulaic songs like “Swinging Doors” and songs that created their own reality, like “Footlights,” “Leonard,” “Shelly’s Winter Love”). He would always sing the songs the people called for – he owed it to his audience, he said – but the others he sang for himself.

Things I learned in a hobo jungle

Were things they never taught me in a classroom,

Like where to find a handout

While thumbin’ through Chicago in the afternoon.

Hey, I’m not braggin’ or complainin’,

Just talkin’ to myself man to man.

This ole’ mental fat I’m chewin’ didn’t take a lot of doin’.

But I take a lot of pride in what I am….

I never been nobody’s idol

But at least I got a title

And I take a lot of pride in what I am.

He did. And there is no one who deserved to more. But remember (sometimes it’s hard): that’s not Merle who grew up in the hobo jungle, that’s Merle casting his poetic eye on the world and, at his best, always finding a place in it for himself.

The last time I saw Merle in concert, he was playing the Ryman with his then-19-year-old son Ben, who had taken over as lead guitarist for the Strangers a couple of years earlier. Ben proved to be a virtuoso performer, incorporating all the outstanding licks from all the outstanding lead guitarists, from Roy Nichols and James Burton to Redd Volkaert, Grady Martin, and then some, as Merle’s face reflected undisguised pride. But that, of course was not the point – at least not the whole point. This was one of the few shows that I ever saw, maybe the only one, where Merle confined himself to electric guitar pretty much exclusively. (Merle had learned to play fiddle in his thirties to be better able to interpret Bob Wills’ music.) But not just electric guitar – he got into a guitar duel with Ben which I’m sure he would have been perfectly willing to concede he could never win, as they traded stinging licks, and Merle was as engaged in every song as I’ve ever seen him. “A lot of people may not realize it,” says his ex-manager Tex Whitson, “but Merle would have been happy just playing guitar.” And now, in his own way, he was realizing that ambition.

If you want to catch a glimpse of Merle as he was that day, check out the link below to video of the panel he did at the Country Music Hall of Fame with longtime Strangers Norm Hamlet and Don Markham earlier that afternoon. He had not been billed on the panel, in fact he didn’t commit to it till the last moment when he showed up unannounced, taking the place of Fuzzy Owen, his oldest associate, and looking like someone who had just wandered in off Lower Broad. Here you’ll see Merle as he rarely presented himself in public: relaxed, engaged, emotional, and funny, with a warmth and graciousness that precludes nostalgia but celebrates instead an unconditional embrace of a shared past. At one point, talking about his ex-wife and lifetime partner Bonnie Owens, he comes close to tears, but what is most striking is the way in which, without ever surrendering that keen-eyed gaze, his face continues to be bathed in smiles. As Merle himself might have put it, quoting from the lyrics of one of his more upbeat songs, “I can’t say we’ve had a good morning, but it’s been a great afternoon.”

Thanks to Peter G. for allowing First to reprint this post from his wonderful blog: http://www.peterguralnick.com. Check it out if you love American music!!