In the wake of Jonas Mekas’ death, First is reposting Bruce Jackson’s tribute to the great film preservationist James Card.

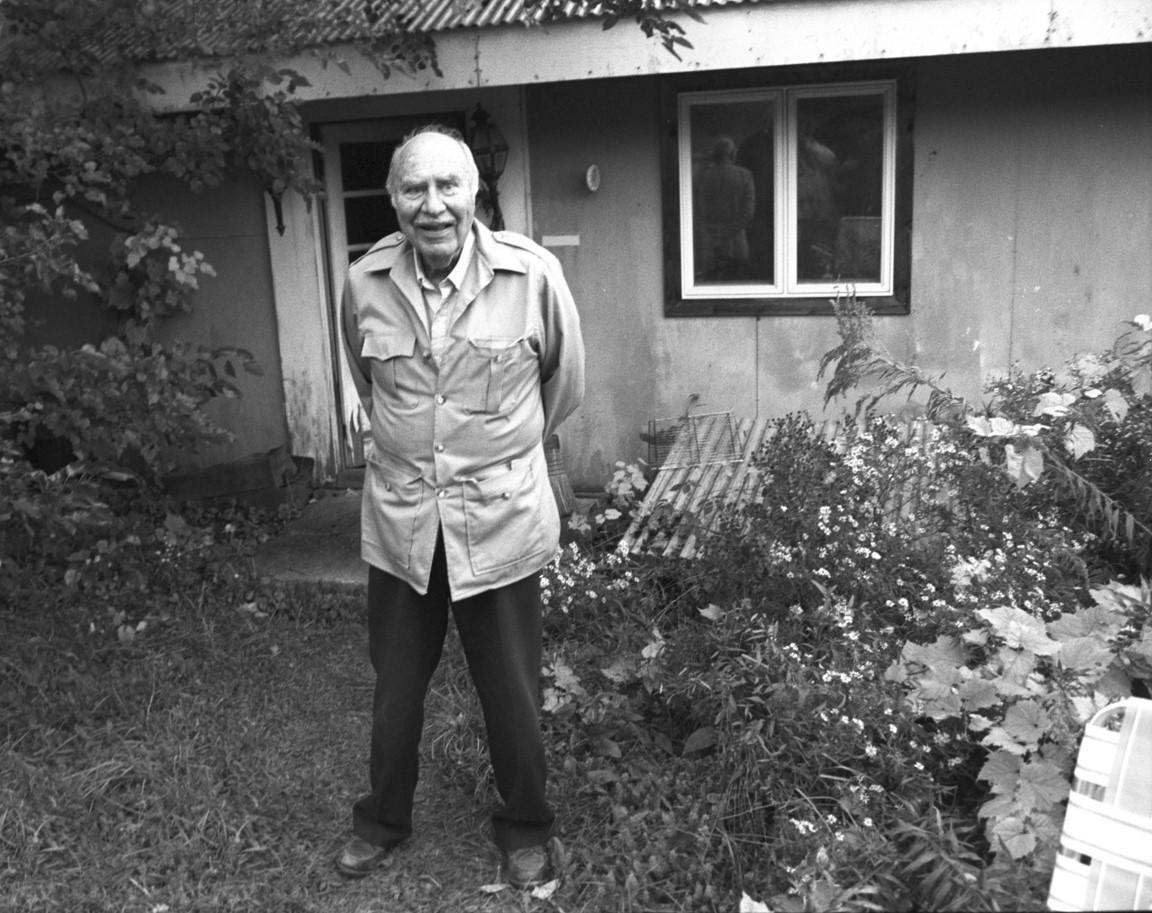

James Card, founder and first director of the film program at George Eastman House International Museum of Photography in Rochester, one of the founders of the Telluride Film Festival, and one of the world’s four great film preservationists, died in a Syracuse hospital Sunday, January 16, 2000. He was 84 years old and had spent the previous four years in the VA hospital in Canandaigua, all but immobilized by a stroke.

Barry Paris, who has written extensively about film, wrote that Card “singlehandedly built the Eastman House collection from a dozen little Edison kinetoscopes into a master collection of more than 5,000 titles, second only to that at the Library of Congress and second to none in private hands. His forte was not just accumulation but restoration, particularly of the most endangered film species, silents. He personally saved some 3,500 films that would otherwise have been lost––obtaining many of them in the Machiavellian ways known only to archivists adept at international wheelings and dealings. “

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

He often talked about being a political conservative but I don’t think he had any politics at all. It was movies, just movies, that drove him. His life was finding them and showing them to people. He describes much of it in his book, Seductive Cinema: The Art of Silent Film (1994).

Jim was enormously generous with his films. Diane Christian and I must have put on a dozen separate film series at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, University at Buffalo, and the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society using rare films from his collection. If there was money to pay for rentals and for his participation he was happy to get it; if there was no money, he’d lend the films and participate just the same. Almost every time we visited him he’d send us home with four or five films he thought we ought to look at or should show our students or friends. Some of those prints were unique in all the world. One semester he taught a seminar on silent film in UB’s English department. At the time, only a few of the students knew how rare the prints they were seeing each week were, though we’ve heard from many of them over the years as they’ve wanted to see some of those films again and have sought them in key collections in New York, Los Angeles or Washington and were told that prints didn’t exist and hadn’t for decades.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

The Chicken Coop Chicken Coop

Jim’s longtime friend William K. Everson, the noted film historian and collector, once said that his idea of hell was to have a room full of great films and no projector to look at them with. Jim heard that and said, “My idea of hell is having the films, the projector, and nobody to show them to.”

He loved showing films to people and he did it whenever he could. He bought a big old chicken coop near the village of Bristol Springs on a hill overlooking Canandaigua Lake. He turned the outer parts into ordinary spaces: living room, kitchen, bedroom, study, guest room, storeroom. The storeroom contained boxes of things, an old Alfa Romeo Spyder convertible that had several critical engine parts on the passenger seat, and a dozen steel cabinets full of film cans. The bedroom was adjacent to the livingroom, and instead of walls it had curtains. The guest room had tables with thousands of movie stills and 78rpm records. That was the ordinary part of the place.

In the center of the building, isolated from light and noise by all the other rooms, Jim built a theater that could seat about 16 people comfortably. There was a screen at one end bracketed by velvet curtains. On one side of the space between the screen and the first row of four chairs was a piano; on the other side was an organ. The room had four steps that went all the way across and on each step except the last were four chairs in groups of two separated by an aisle. The top step had five chairs. He named the place Box 5, which he had named all his private projection rooms over the years. Box 5 was where the protagonist sat in The Phantom of the Opera, one of his favorite films.

From the outside, the Bristol Springs house was a big old shed with a big old barn in mild disrepair to the left and a small unpainted barn just in front. Jim liked it that way because nobody ever thought to burglarize the place when he and Jeannie, his lovely and infinitely patient wife, were up in East Rochester, where they lived. No vandal or crook ever realized that the former chicken coop held a huge collection of rare films or that the interior of the small barn was a duplicate of the saloon in William S. Hart’s Hell’s Hinges (1916). It was brilliant set design.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

The Saturday Regulars

During the warm months, Jim invited people down on Saturday and Sunday afternoons to watch films. Jeannie always made a cake and hung out before and after the films. She sometimes slipped off during the screenings but was quick to point out that she’d watched the film with Jim the day before because he always liked having someone with him when he watched films and she was often the only person around for that duty.

Sunday, he told me, was local people, neighbors; Saturday was everyone else. Once a month from April through November Jim would send out an invitation, a four-page booklet with a still from the film and the date and time on the cover, credits and a summary on the two interior pages, and a bit 0f prose or poetry that had caught Jim’s fancy on the back, along with the title and date of the next screening.

A core of regulars was there every screening Saturday: an old friend of Jim’s from Kodak (he’d worked there before going to Eastman House), a TV newscaster from Rochester, a painter from Buffalo who was one of the few survivors of the army company John Huston filmed in “San Pietro,” the film scholar Constance Penley before she moved to California, the two film curators who had succeeded Jim at Eastman House. The great silent movie pianist Philip Carli was often there, as was composer David Diamond, and Barry Paris, who drove up from his home in Pittsburgh for the screenings. Barry was up more frequently when he was working on his biographies of Louise Brooks and Greta Garbo. Stephen Bach, author of Final Cut (an insider’s view of the unmaking of United Artists in the Heaven’s Gate cost overrun fiasco) was there while he was working on a biography of Marlene Dietrich. Some visitors were there to interview Card, some to see a specific film, some because one of the regulars brought them along. Jim encouraged all of us to bring friends––once. Repeat visits were up to him. If Card liked the visitors, they’d find themselves on the invitation mailing list; if he didn’t, they just weren’t mentioned any more.

When all the people Jim especially wanted to be there had arrived, we’d go in to the theater, walking through the corridors on either side of the building that were lined with posters, old projectors and cameras, and other film memorabilia. Sometimes he’d have selected the film for just one person in the group, though Jim rarely told the rest of us or even the person that fact. Usually he’d give a brief introduction. Sometimes it was about the film we were going to see, sometimes it was one of his set pieces about film in general.

One of his favorite set pieces was about how there’s no there there. You watch the screen and seem to see smooth motion, but the actual motion of the film past the gate is stop and go, stop and go. The screen seems bright all the time, but in fact it’s dark more than it’s illuminated in order for the film to move on and another frame to move into place. The pictures seem solid and full but move close to the screen and it’s unintelligible grain. The motion and the constant light were illusion, mere artifacts of the time it takes the human optical system to process an image, and the smooth images were merely the result of distance. What’s really there? he’d ask. Nothing, he’d say, immediately answering his own question. Then he’d grin fiendishly and say, “But of course it’s there. And we all see it, don’t we?” And then he’d go into his projection booth and start the movie.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

What We Saw

He showed some sound films, but the films I remember most were silents, each of them screened with a music tape Jim would prepare each time. He’d try to get the audiotape and film reels to begin and end simultaneously, but one was almost always a little ahead of the other, so it wound up with Jim hopping around in the projection booth like Grandmaster Flash at a serious blast.

I particularly remember Louise Brooks in G. W. Pabst’s Pandora’s Box (1929) and Diary of a Lost Girl (1929), Pola Negri in Mauritz Stiller’s Barbed Wire (1927), Joan Crawford in Harry Beaumont’s Our Dancing Daughters (1928), and John Gilbert and Jeanne Eagles in Monta Bell’s Man, Woman and Sin (1927). I also remember Vigo’s L’Atalante (1934), von Sternberg’s Docks of New York (1928), Murnau’s Sunrise (1927), DeMille’s The Squaw Man (1913), Browning’s The Unknown (1927), and Borderline, a 1930 silent film with Paul Robeson.

Sometimes, in the discussions afterwards, there’d be a polite silence and then someone would say, “That was just awful,” and Jim would, likely as not, agree, and go on to tell us why. “Then why did you show it to us?” someone would say. He’d tell us something in the film that he thought of particular interest, worth watching, and usually we’d wind up agreeing with him. Sometimes he’d shrug and say, “I just like it.”

On rare occasions, the films were brought to the chicken coop by someone else. Bill Everson brought Griffith’s America (1924) and Card was delighted that it was the British version. The American version, he said, glorified the American victory in the Revolutionary War, but that wouldn’t sell in Great Britain, so Griffith made another ending that downplayed the triumphal notes and focused instead on British bravery and dignity. Jim didn’t like Griffith, thought him vastly overrated and credited for inventing many film techniques that others had used previously. He delighted in finding and showing us films which he could preface with, “Now Iris [Iris Barry, film curator at the Museum of Modern Art] says Griffith invented this. As you will see today….”

It wasn’t just Iris Barry: whenever he found any major film historian or critic stating categorically that something had been done for the first time in a specific film he’d set off to find some earlier film with exactly the same technique or device. Because of him, I hardly ever use that phrase any more without qualification. I’ll say, “So far as I know, this is the first time…” or “Some people say this is the first time….” or “This is one of the earliest instances of….” Once in a while I slip and say it and I have an immediate vision of Jim saying, “That’s what you think, boyo.” Boyo: that’s what he called me whenever he was correcting me on a point of fact.

He liked to show us the great silent film actress Pola Negri singing and whistling “Paradise” from a deservedly obscure film, A Woman Commands (1932). The first time I saw it I thought the song and the performance were both enormously corny and I laughed aloud. But Card wasn’t playing it for a gag. He kept finding excuses to run it. Sometimes he’d run it before or after the day’s feature; sometimes he’d tuck it into a string of shorts. After a while I started really liking it, and then one day, driving back to Buffalo, I found myself whistling that damned song in the car again and again. Couldn’t get it out of my head. Still can’t.

Jim handled occasional glitches with great élan. He gave one film du jour a grand introduction, went up to the booth, laced it up, and realized that someone had placed another film in the can. He looked around for a while and couldn’t find the film he’d planned on showing us. Hardly missing a beat, Jim said there was an old public television program about Gertrude Stein he’d long wanted to show us but had never found a proper occasion and he guessed this was it. It was horribly faded––there were no blues left––but it was fascinating. We all talked about it for an hour afterwards.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

The Bengali Epic

He telephoned to say that Diane and I must meet him at the Dryden Theater in Eastman House the next day to watch an Indian epic film. “It’s 5½ hours long, entirely in Bengali, not a word of English. It’s a fabulous love story. You won’t be bored, I promise. You’ll be able to follow the action perfectly.” I said I didn’t want to drive to Rochester for a 5½-hour film in Bengali without a word of English in it. “You have to,” he said. “When else will you get an opportunity like this?” Diane and I went. It was just the three of us in the theater. The film was maybe two hours long and it had English subtitles. Afterwards I yelled at him about the misrepresentation.

“What are you complaining about?” he said. “I told you you wouldn’t be bored and that you’d be able to follow the action perfectly.”

“You said it was 5½ hours long.”

“Would you rather it had been?”

“No, of course not.”

“So?”

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

The Bulgarian Mope

After one Saturday screening he said I had to come to Bristol Springs the next weekend with my movie camera, lights, and several rolls of negative so I could shoot a film for him. It was based on a corny country-western song called “Almost Persuaded” and it was going to star a very gloomy Bulgarian woman, a UB graduate student who did her hair exactly the way Louise Brooks had done hers in A Girl in Every Port. Card first saw that movie at the age of 12 or 13 and he’d fallen in love on the spot. The student’s gloominess reminded him of Louise at her worst, he said, and he was “ensorcelled by her.” I said I was busy with work, I didn’t want to do it, and moreover it was a silly thing to do. “I’ll pay you to do it,” Jim said.

“You don’t have any money,” I said, “and I wouldn’t take money from you anyway.” “You’ll take that poster, though.”

He had me and knew it. He referred to a 1927 Cassandre lithograph of curved railroad track he knew I had long coveted. Only a few months before, when he announced that he was selling a lot of his stuff so he’d have money to buy more films, I’d asked him about that poster. “That’s not for sale and you couldn’t afford it anyway,” he’d said.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

The Germans

Two friends from Berlin visited us in Buffalo. The woman, Renate, had heard of Jim and wanted to meet him. We called, he said bring them down, and off we went to the chicken coop. When we arrived he said he had a program all set up for them. I forget the short, but the main feature was Leni Riefenstahl’s Tag der Freiheit: Unser Wehrmacht (Day of Freedom: Our Army), the film she presumably put together to mollify German military officials miffed because Triumph of the Will hadn’t shown enough of their hardware. The film’s final shot will give you an idea of its tone: a Luftwaffe squadron flying overhead in a swastika formation is superimposed on a Nazi flag. I was immensely embarrassed: just because my friends were German, Jim had decided they deserved a diet of Nazi propaganda. Both of their fathers had been killed in the war; her mother had been shot down on the street by a drunk Russian soldier after the surrender. The last thing in the world they needed to see was flying swastikas.

When the film ended, Renata said, “I don’t know what to say.” I bet you don’t, I thought. She went on: “We’d never see films like that in a lifetime in Berlin. I’m really grateful to you for this. I don’t know how to thank you for letting us see them. We’ve only heard about them.” Jorn said, “I’ve always wanted to see that film but never could. Thank you.” Jim looked at me and grinned: he’d known exactly what I’d been thinking.

He told them his favorite war story, how he caught the start of World War II on a single roll of film. At the end of August 1939, he’d filmed some tanks in Berlin. A few days later he and a friend were in Danzig when Germans tanks rolled into the city, marking the invasion of Poland. He took out the camera and began filming again. “In the viewfinder, I saw the lead tank and it was the same tank I’d filmed in Berlin two days earlier. The same markings, the same numbers on its side. The same tank. I knew what I had: a single strip of film with no cut, no splice. The start of the war.” Almost immediately he was arrested and he and his friend were taken to a building where they were interrogated at length. They couldn’t be mere students as they claimed, so for whom were they spying and for whom were they making those films of German armor? Then, Card said, a Nazi officer said, “I really like Americans.” The officer told them he had been a prisoner of war in New Jersey in World War I and he had been very well treated. “I always wanted to repay Americans for that treatment and now I can. There is a train leaving Danzig in twenty minutes. Be on it.” Jim asked about getting their belongings from the hotel. “Not enough time,” the German officer said. Jim tried to pick up his camera but the officer pushed it out of his reach. “Go get your train. If you miss it, there’s nothing I’ll be able to do for you.”

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Burial on the Lawn

Jim rarely talked about his career at Eastman House, though he had spent thirty years there and had made its film collection one of the most important in the world. He said that one condition of his pension deal was that he’d never discuss how and why and under what terms he retired. He did refer with some bitterness to a fire there involving some old nitrate films. “They tried to put that blame for that on me. Improper caring for films. Me!” After the fire, he said, he’d taken about 500 of the volatile film cans and had buried them on the Eastman House property. No need to worry about spontaneous combustion in the cool and airless underground. Some years later, Eastman House officials remembered the buried films and began digging up the grounds looking for them. Jim chuckled with obvious glee as he read aloud a newspaper clipping describing their efforts. “They did everything right except the one thing they should have done.”

“And what was that?”

“Ask the one person who knows exactly where those film cans were buried.”

“And he’s not going to offer the information on his own?”

“Not if they don’t think he’s worth asking for help.”

He was constantly aware of the permanent disappearance of films and he was always trading with other collectors, pursuing leads about someone who had a closet full of film cans left by an uncle, buying, selling, hustling, conniving. Once a local library decided it could no longer afford film and was therefore shifting to videotape. It gave him everything. The Hell’s Hinges saloon was packed with hundreds of small and large film cans, some of them obviously nitrate stock. I mentioned this and Jim said, “Of course it’s nitrate. Something that old, it’s all it could be.” I reminded him of what happened at Eastman House, of how volatile nitrate stock could be. He was unconcerned. “People overreact to that sort of thing,” he said.

He said that the worst film fire he knew was not the least bit spontaneous; it had been carefully planned and carried out. One of the major studio executives told him they were discarding most of the old negatives to make room for newer and more profitable stuff. Jim pled for the negatives. The executive told him he was welcome to whatever he wanted and sent him a thick list of the holdings. “Check off what you want and it’s yours. We’ll burn everything else.” Jim checked off what he wanted and waited. One day a tractor-trailer arrived at Eastman House and workers began unloading the cases of film. Jim went to inspect his new treasure and was horrified to find that every can he looked at was marked with the name of one of the films he hadn’t wanted. Not a single one of the films he’d checked was in the semi. He called Hollywood and was told that all the films he’d wanted had been sent to him and all the others had been destroyed. Jim said that the truck contained the wrong films. “Then I guess we burned the wrong films too,” the person at the other end of the line said.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Louise

I said that Card had fallen in love with the screen Louise Brooks in 1928. Twenty years later he established a very complex relationship with the real one. She was at the time living in Manhattan, a bloated drunk who split her time between her bed and a barstool. He got her interested in living, got her to take up writing, and was the person primarily responsible for the international recognition she enjoyed in her later years. He brought her to Rochester and helped her establish a new life. They were for a time very close, and then they fought bitterly.

We all loved Pandora’s Box, in which she’s stunningly beautiful and at the end is murdered by Jack the Ripper. We saw it at Box 5, we showed it in two or three different film series here in Buffalo, we showed it to friends at our house. One time when we watched it Card said, in a matter of fact way, “You’ll be interested in this, Bruce, because you’re a criminologist: When Louise and I were really hating each other I devised the perfect murder. It was really perfect.” I asked him what he’d come up with. “She smoked in bed and she still drank a lot. I don’t know how many times she nearly burned herself up with those cigarettes in bed. I thought I’d pour some volatile fluid around the bed, one that would burn totally. Then I’d put magician’s flash paper all around her. You know, that stuff that bursts into flame at the slightest spark and leaves no residue? When she was drinking, she wouldn’t notice things like that. She get into bed, she’d smoke, and––ha!––she’d go up in smoke.”

“That’s horrible, Jim,” Diane said. “To burn her to death?”

“I didn’t do it,” he said. “I only had the idea.”

“But,” Diane said.

“Why didn’t you do it?” I said.

“We were fighting then, so I never had the opportunity. Then I wasn’t that mad any more. When we got to be friends again I told her about it. She said it was a wonderful idea, that it was a perfect way to murder someone like her, and she could understand why I’d come up with it. Louise always liked good plots.”

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Rat Things

The last time we saw him was in the VA hospital in Canandaigua. He was watching a videotape of an obscure Russian film which he said wasn’t very good. I asked him why he was watching it, then. “Because I like it,” he said. He told us that the entire staff of the hospital were sadists and that his room might appear decent enough now, but at night it was full of rats. “They’re all over the place: on the walls, the floor, under the sheets.” Diane tried to talk him out of it. She told him there weren’t REALLY rats in the room, that it was just a delusion. “Oh yeah?” he said, having none of her Pollyannaish logic. I said, “And what do the rats do?” He looked at me like I was a moron: “Rat things,” he said, as if that said it all, which I guess it did.

There is a poem by the French symbolist poet Stephen Mallarmé I think of when I think of Jim’s relationship to films. The title is “Don du poème,” gift of the poem. It tells of a poet who writes the poem in the dark of night and brings it to his wife in the early morning because only in her hearing or reading is it brought to life. The poem needs both the artist and the reader or listener to exist because only in the moment of being experienced does it have life.

So it was for Jim Card with movies: in that moment of being experienced they came alive, and so did he, and so for me shall he continue, when I sit in those darkened rooms and experience those images that only the most foolish and bereft of imagination among us would say aren’t really there. They’re there, those images, as real as you to me or me to you.