“A Mile from the Bus Stop,” 1955, By Jess Collins

Why start a piece on Greil Marcus’s What Nails It with Jess’s painting of Pauline Kael and her daughter in a Berkeley park?

Not only because I want its greens. Marcus devotes the second of the three chapters in his short new book to Kael who taught him what criticism could be. His felt tribute to his friend (and fellow Californian) lies at the heart of his book.

Marcus hasn’t been a confessional writer in the past, but What Nails It goes inward, probing what’s behind his drive to surprise himself with his own words. Composed fast—after seasons when he couldn’t walk up a flight of stairs and nearly a year of silence due to personal health crises—Marcus’s comeback is freewheelin’ fun.

It was a two-Negroni read for me (what the hey, only $13 a pop—with house gin—at my spot on 72nd St.). I sensed I’d want the second drink when a retrospective Marcus mulled over how he came up with the phrase: “slow bacchanal.” That, in turn, called up another image that got under my skin once I began reading him in the 70s. Marcus was writing about dub—Garvey’s Ghost (I think)—when he conjured up “surf music with slave ships on the horizon.” Down the line, I’d get (much) more from other explorers of “the black music of two worlds” but out on the street, juiced by Nails’ ninety-page scroll, I found myself acting on a prompt that first became an impellent for me after Marcus steered readers to The Sun Sessions. Buzzed and stirred, I race-walked uptown roaring “That’s Alright, Mama”—as other West Siders made room: Here comes another howling mad New Yorker. Elvis’s electric version of Arthur Crudup’s blues has been one of my go-to tunes for a cappella after dark ever since I locked on it post-“Presliad”—the Elvis essay in Marcus’s breakthrough book Mystery Train. I may have murdered “That’s Alright Mama” more often than “Take It or Leave It” or “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry”[1] Who can resist trying this blues? (You can watch Sam Phillips do a chorus at the end of this clip as a benign (!) Ike Turner muses he’s never heard Sam sing. And have you heard the Beatles nice version?) Elvis et al. passed this gift on to everybody everybody…

Marcus has heard America singing. He’s aware, though, he hasn’t always kept faith with the country’s promise. He evokes grad school fails, contrasting his pedantic practice as a youthful instructor who quashed student voices with the teaching of Am Studs profs who set him and his cohort on fire. His self-criticism amounts to more than self-laceration. It’s tuned to Marcus’s democratic theme. What Nails It reaches its summit on this front when Marcus exposes a priori behind the 1990 “High and Low” show at MOMA, which was co-curated by an Art Worldly eminence, the late Kurt Varnedoe. Marcus zeroes in on Varnedoe’s companion book to the exhibition, A Fine Disregard: What Makes Modern Art Modern…

The title—and the view of the world that it spoke for—came from a stone marker that stands at the gates of the Rugby School in England, one of the most aristocratic schools in the world. Varnadoe, who attended Rugby, placed all of modern art on this stone, which commemorates the exploits of one William Ellis Webb, who in 1823, “With,” the stone says, “a fine disregard for the rules of football as played in his time, first took the ball in his arms and ran with it, thus inaugurating the distinctive feature of the rugby game.” But the working word in the title is less “disregard”—than “fine.” That is, one is being assured that modern art remains art. More than that, it remains the province of the sort of people who for centuries have attended the Rugby school—or who sit on the boards of art museums. One is being told modern art will not go too far—say “disregard” without the modifier and you have no idea what kind of riff-raff you might let in next.[2]

Marcus’s more populist modernism places Jackson Pollock’s magic in the same realm as garage rock:

…I walked into the Peggy Guggenheim museum in Venice and stopped in front of a Jackson Pollock’s 1947 Alchemy, one of his first poured paintings, one of his first experiments, or proofs, that by practicing an arcane art you really could turn not merely a few cans of household paint into millions of dollars, but turn something anyone might have in a garage into something no one could have predicted and that had anything been different on the day it was made would never have existed at all.

I’m guessing Marcus is alive to how his “millions of dollars” echoes Sam Phillips’ famous pre-Elvis line: “If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel,” Phillips is said to have said, “I could make a billion dollars.”

It was rock ‘n’ roll that got Marcus going. (I’m recalling just now his beatific replay of The Beatles’ “incandescent” ode to “a place/where I can go, when I feel low…”)[3] The music gave him momentum (and a gig) but he’s aware there was something backward about his sense of time in his youth. He tells how he was a history boy, lost in the mythos of good wars and sports legends. Me too. Though I took it to another (doofus-Proustian?) level. When I was a child, I’d seize on a blank moment of dailiness and try to force it on my memory. There was no future in my attempts to find the past in an empty present. I’d end up, days later, with nothing but vague traces of my original aim to memorialize an un-momentous moment. Traces that kept me trying to produce tradition synthetically. I figured out later that my impulse to capitalize on dead time was a private property of a middle-class structure of feeling.

Rock ‘n’ roll tore that playhouse down (for two or three minutes at a time). Nobody young in the 50s or 60s needed to contrive a live record of lifelessness. The solution was in the air. Are you experienced? Asked and answered (even if you came to respect cats who chose Otis Rush over Hendrix).

What Nails It doesn’t focus on how rock ‘n’ roll amped up Marcus in his schooldays but I’ll step into the breach with a passage from an account of my own pop life first published in First about 25 years ago.

I remember wanting the Beatles’ “Help” for what felt like months. When I finally got the album (on a proud spring day), the record’s segues offered me musical equivalents of my earlier frustrations and fulfillment. Instead of skipping this movie soundtrack’s crapola instrumentals (Muzak variants of “Can’t Buy Me Love” etc.), I’d sometimes choose to endure them, secure at last that Lennon and McCartney’s promesse de bonne minutes was no longer days or hours away.

I couldn’t wait for the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers. I sang “Sister Morphine”—as I cut the lawn—before I’d ever played the song. Turned on by the title (which I’d seen listed in an album preview somewhere), bored mad by the chore, I made up my own melody/lyrics and punked up the mower’s vacant volume.

Enough of my noise. Here’s Marcus musing on how Let it Bleed—the Stones album before Sticky Fingers—warned his gen that “a thrilling time when anything seemed possible was about to turn to Stone.” That hard stop gets a kind of personal coda when he recurs to Let it Bleed’s “Gimme Shelter,” recalling how the song poured out of his car radio on a freeway in 1989, twenty years after its release. Struck by how the Stones and Merry Clayton were still pushing him to the edge of the end of Sixties, he went from one beginner’s mind to another when a car cut front of him: “I had to change lanes without looking, and thinking, as my heart went back down in my chest when I realized the lane was clear, that if I had to go, there were worse ways.”

How did Morrissey put it in “There Is a Light that Never Goes Out”?[4]

And if a double-decker bus

Crashes into us

To die by your side

Is such a heavenly way to die

And if a ten tonne truck

Kills the both of us

To die by your side

Well, the pleasure, the privilege is mine

(I won’t choose between “Gimme Shelter” and “There Is a Light That Never Goes Out” but I hear The Smiths’ Johnny Marr: “…when we first played ‘There Is Light’ I thought it was the best song I’d ever heard.” He wasn’t too far gone.)

The Smiths never came through to Marcus. And I skipped them in their 80s moment, which meant I had no shot with one shortie who got away—a Trini Afro-Indian beauty (who’d make it to the big screen as a “rose bearer” in the wedding scene of the bad Eddie Murphy movie, Coming to America). I met her when she worked the phones upstairs in a law firm where I dispatched limos for the partners in the lobby. I tried to get her to come see Al Green at Radio City Music Hall, but she was a Smiths’ fanatic. If only I’d heard the “Light”![4]

“Sex is the great leveler, taste the great divider,” per Pauline Kael. Marcus quotes Kael torching men who seemed “at least remotely possible” until they talked up a movie she hated, “frequently a socially conscious problem movie of the Stanley Kramer variety…

Boobs on the make always try to impress with their high level of seriousness (wise guys with their contempt for all seriousness).

It’s experiences like that that drive women into the arms of truckdrivers—and, as this is America, the truckdrivers all too often come up with the same kind of status-seeking tastes: they want to know what you thought of “Black Orpheus” or “Never on a Sunday,” or something else you’d much rather forget.[5]

Kael’s punchy lines haven’t lost their snap (though her diss of truckers makes me wish someone had shushed her by playing “Six Days on the Road”). Citizen Kael handed Marcus the keys to his vocation. Passages like the next one from her “seven thousand-word-polemic-cum-essay-cum-critical argument-cum-critical entertainment” on Bonnie and Clyde gave him a map:

“Bonnie and Clyde” brings into the almost frighteningly public world of movies things that people have been feeling and saying and writing about. And once something is said or done on the screens of the world, once it has entered mass art, it can never belong to a minority, never again be the private possession of an educated, or “knowing” group. But even for that group there is an excitement in hearing its own private thoughts expressed out loud and in seeing something of its own sensibility become part of the common culture.

Kael’s credo seems to have been an audacious sublation of Hannah Arendt’s famous lines from Eichmann in Jerusalem.

It is in the very nature of things human that every act that has once made its appearance and has been recorded in the history of mankind stays with mankind as a potentiality long after its actuality has become a thing of the past . . . Once a specific crime has appeared for the first time, its reappearance is more likely than its initial emergence could ever have been.

A connection that’s probably occurred to Marcus who once quoted Arendt’s lines in a piece of his own about American pundits’ not-knowing responses to 9/11. More on that anon.

Marcus dug Kael’s public intellectuality and demotic talkback—the way her truth-attacks busted down doors of exclusory Urban Haute Bourgeois perception. (She broke glass ceilings too.) Marcus’s loving account of her un-UHB-ish politics of culture had me retracing Kael’s wonderful run of affirmations starting with Bonnie and Clyde. Films she championed—Godfather(s), The Landlord, The Last Detail, Mean Streets, Dog Day Afternoon—were in the minds of my friends and I as we came into New York City. Her beloveds also helped us make sense of our intimate lives. Warren Beatty’s anhedonic Clyde must’ve prepped thousands of wannabe Don Juans for what would happen to their permanent hardons (Timber!) when they fell balls-to-the-wall in love. Later on, Brando (and Bertolucci) would dance us into the post-vanilla era of erotic variousness.

It seemed that Pauline might ride with us through all our ups and downs. Her instinct for what was vital in pop life, though, faded once America’s New Wave crested. She began to lean more and more on her in-crowd of Paulettes as American cinema mattered less and less.

Yet Marcus is right to recall how Kael was a generational talent—a “critical patriot.” Long after she quit being the New Yorker’s regular movie reviewer, her best essays were still touchstones for pop lifers of a certain age. When we were trying to get First to fly in the 90s, I sensed we were headed for something better than détente with Ellen Willis (who’d end up contributing a piece to our first First and helped pay our printing costs) once Kael’s words connected us. When our original crew’s film critic, Armond White, spoke at an NYU event (at the invitation of Ellen), he quoted a passage from Kael’s “Trash, Art and the Movies” without identifying the source and asked if anyone in the room could tell where it came from. Ellen and I both slowly raised our hands and then put them back down quickly when we realized no-one else had raised theirs.

I’m recalling just now how Kael’s stuff must have been in the nimbus when my older sister, Joel DeMott, reviewed movies for her college newspaper in the mid-60s. Not that she needed cues. Still, I bet Kael’s dares were in Jo’s ear when she dispatched The Wild Angels and The Trip…

The director, Roger Corman, picked sensational topics—Hell’s Angels and acid. Then he shot some film, dressed it up with a big-beat score, and prayed nobody would discover what he is: an idiot.

The star didn’t get away clean:

As for Peter Fonda, who plays the chief tripper and head Angel: I’ve never been so bored watching somebody so beautiful.

Jo could’ve been a critic but she was made to film. Her Demon-Lover Diary (1980) and Seventeen (1983), which she co-directed and shot with Jeff Kreines, are peaks of American direct cinema. Marcus reviewed Seventeen (dimly) for Art Forum in the mid-80s. I’m going to risk an aside on his Seventeen piece, despite my distinct bias, since Marcus’s back-in-day unresponsiveness to Jo and Jeff’s film about coming of age in Muncie’s Shed Town brings home why one pivot in What Nails It amounts to moral progress. (Of course, for Marcus, as for all us, it’s one step up and…)

Marcus wasn’t engaged by the black and white working-class kids whose lives were caught on the wing (though no one was headed for blue skies) in Seventeen. He shrunk his response down to a sequence in the film that began at an “ordinary party” where he allowed “the viewer doesn’t feel like a guest…the feeling in the crowded rooms is very intimate.” One partier, Keith Buck, got stuck in what Marcus termed “an amazing, ugly drunk: a rant, where the drunk locks into a couple of phrases and can’t let them go.” Marcus found “the drunk’s” behavior unfathomable. While Keith’s midnight crackup is hard to watch and/or suss, he seems to have been trying to breathe his own dicey life into a “tough-as-nails-like-me” soul mate who was in the hospital that same night fighting to live after a car-crash. Keith’s buddy didn’t make it and in the next scene—the day after the kegger—we’re there when Keith calls up the Muncie radio station to dedicate Bob Seger’s “Against the Wind” to his Shed Town friend. When the song comes on, Keith and his crew (with one parent) are overwhelmed.

Marcus was unmoved. With a fine disregard for the grief on the screen, Marcus chose to brood about the “tyranny of a shallow song”—overexplaining why Seger’s “sentimental” “Against the Wind” wasn’t as moving as his “Night Moves.” Marcus wasn’t wrong about “Night Moves.” But his imperviousness to Seventeen’s screening of a (“very intimate”) collective tremor hints how those of us who come up middle class tend to stay above it all—looking down on the “we” that undergirds growing up in—and checking out of—America’s working class.

Anyone born into the bourgeoisie like Marcus (or me) is tempted to commit commanding heights criticism. (Rank snark is alluring as well.) Sometimes, though, American intellects whose brains were saved by rock ‘n’ roll, remember to climb down. Brits tend to have their uses on this front, since they come up knowing class matters. Marcus cites the late scriptwriter Dennis Potter (whose father was a Welsh coal miner) in What Nails It. Marcus lauds Potter’s “anti-musicals”—Pennies from Heaven and The Singing Detective—before citing a passage from a Q&A with Potter that blows away Marcus’s take on Seventeen’s “Against the Wind” scene.

“I don’t make the mistake of thinking that high culture mongers do of assuming that because people like cheap art, their feelings are cheap too,” he said…

When people say, “Oh, listen, they’re playing our song,” they don’t mean “Our song, this little cheap, tinkling syncopated piece of rubbish is what we felt when we met.” What they’re saying is, “That song reminds me of the tremendous feeling we had when we met.” Some of the songs I use are great anyway, but the cheaper songs are still in the direct line of descent from David’s Psalms. They’re saying, “Listen, the world isn’t quite like this, the world is better than this, there is love in it,” “There’s you and me in it, or “The sun is shining in it.” So-called dumb people, simple people, uneducated people, have as authentic and profound depth of feeling as the most educated on earth.

Potter’s testament isn’t quite apt for Seventeen. (You’d have to be truly benighted, not just class-bound, to imagine the movie’s anti-heroine, Lynn Massie, was “dumb.”) Yet Potter’s Brit expressionism serves as a good segue to Seventeen’s ending. The movie’s last scene turned out to be a prophetic fuck-off to all the reps of the assumed dominant Mind-in-America, ranging from William Buckley to Nation-istas, who’d trash the kids in the film even as corporate/media poohbahs schemed to ban Seventeen from PBS. (ICYMI, Benjamin DeMott’s The Imperial Middle: Why Americans Can’t Think Straight About Class concludes with a chapter spelling out what happened to Seventeen and here are Jo’s own definitive notes on the making of the movie and how it induced a moral panic fueled by hustlers and hegemaniacs.[6])

Lynn Massie takes the wheel in Seventeen’s send-off. Her girlfriend sits beside her in the front seat, rolling joints. Stars on 45’s disco mix of Beatles classics gets the girls singing along as they’re getting high. Freeze frame of Lynn, cut to the credits and to the discofied version of a song where England’s working-class heroes tell U.S. culturati the news: “You’re gonna lose that girl.”

A son of privilege like Marcus wasn’t well-placed to track someone like Lynn. (Just as Pauline Kael’s “truckdrivers” were irreal to her.) Yet I don’t want to diminish Marcus’s cultural range. His will to connect art-life with everyday life in What Nails It distances him from wannabe aesthetes (and most academics). There’s nothing pious about his criticism in What Nails It, even when he’s bowing to what’s sacred. Take his plain, human account of how he was overmastered by Titian’s “Assumption of the Virgin” in a Venice church. His unshowy prose brings you near the painting…

I stopped and looked up at it. I walked to the back of the room to see it from a distance. I walked up to the base again. I did this many times.

I was trying to leave the building, and every time I reached the door I found myself pulled back in. I couldn’t get out. I was trapped by revelation.

Yes I said to myself, I finally understand, The only great art is high art. And the only high art is religious art. And the only truly religious art is Christian art. Three things to the bottom of my life I don’t believe—and I was reduced to a puddle of acceptance.

Marcus got over his revelation, but the experience “stayed with him,” teaching him art’s highest purpose is to “tell us, make us feel, that what we think we know we don’t.”

Though in my case, Marcus’s move in his final chapter from “Assumption of the Virgin” to Dennis Potter on the Psalmist was confirmatory. His flow echoes what I think I know, having been schooled by Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, about the profound connection between High Christian art and Potter’s truth: “…simple people, uneducated people, have as authentic and profound depth of feeling as the most educated on earth.” Baby humanists, like yours truly, learned from Auerbach’s wayback machine to link Western aesthetics with democratic imperatives. But Mimesis isn’t biblical to Marcus. I doubt he’s felt called to get real about “the representation of reality.” He seems to be more of a Wilde man. (Pre-prison ballad and pre-De Profundis.) Marcus’s own method chimes with Wilde’s prescriptions in “The Artist as Critic“: “To the critic, the work of art is simply a suggestion for a new work of his own, that need not have any resemblance to the thing it criticizes.” When Wilde flipped his own script in “The Critic as Artist,” he might’ve been clearing ground for Marcus: “his object will not always be to explain the work of art but he may rather seek to deepen its mystery…He will look upon Art as a goddess whose mystery it is his province to intensify, and whose majesty his privilege to make more marvelous in the eyes of men.”

I don’t share Marcus’s faith in occultation. His summoning of mysteries and intensities has sometimes seemed willful. Yet his new book of marvels doesn’t seem over the top. Take his invocation of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. I hadn’t given two shits about Lynch’s films for decades but What Nails It’s passages on Blue Velvet’s hyper-real suburban imaginary seem lit from within. Marcus’s attentiveness to Lynch’s bent Americana adds texture to Ta-Nehisi Coates’ outraged vision of “The Dream” on the other side of red-lines (and Shed Towns).[7] Marcus clocks how Blue Velvet melds personal with cultural memory, proving Lynch was truly hip to the hippocampus. And when Marcus recalls how the film’s detective story begins with “an ear in the field,” his own mythography seems to aim readers toward last summer’s attempted assassination. Though maybe that’s because Marcus’s return to Blue Velvet is part of a double feature that includes The Manchurian Candidate.

Marcus’s ruminations on those movies made me wish he’d take up That Sweet Smell of Success (1957), which I made a point of watching around the time David Pecker testified at Trump’s trial last spring. The shape of foul things to come was all there in this amazing film about dirty business conducted in New York City’s café society by 50s gossip guys. It was eerie to feel Burt Lancaster channel crazed A-List adrenaline the night after Pecker detailed how he’d arranged with Trumpers to plant stories in The National Enquirer during the 2015-16 campaign. I caught That Sweet Smell because the revelator George Trow commended it as a guide to media-men like Walter Winchell who made up the mind of lonely crowds in the 50s.

When it comes to the transition from the American Century to our Kali Yuga’s cultic lunacies, the late Trow’s foresight remains uncanny. Though his knack never gave him much pleasure:

In my essay of 1980, Within the Context of No Context, I predicted that television would establish the context of no context, and then chronicle it. Well, I’ll give myself a little credit here. That began to happen in the 1980’s, the mid 1980s, and by 1990 we had reality television, tabloid television, trash TV—many different forms that had suddenly morphed from entertainment into reporting. And if you think it was fun to see that happen, you are wrong. There’s nothing fun about being right if what you’re right about is the triumph, or temporary triumph, of the inevitably bad.

If you’re beginning to wonder where this is headed, I’m pretty sure my Trovian turn is licensed by Marcus’s own latitudes. Besides, I’m not just asking you to trust me…

Trow’s “patented thinking voice” is often on the mind of Timothy Crouse, the author of the echt pre-web press critique, The Boys on the Bus:

Everything Trow did seemed to have a reason, determined by an arcane code I could never crack, and which I’m not sure even he was fully aware of.

The last time I read the chapter about the New York Times in [My Pilgrim’s Progress] I was struck by the fact that one of the four stories he recommended following was…Ukraine. This of course was 30-odd years ago. I wish I could ask him how he got to that. But then I wish I could ask him a lot of things.

Trow’s precognition informed the last piece he published before his death—his takedown of Dan Rather, “Is Dan Mad?” Long before Rather’s botched investigation—based on forged documents—of George W. Bush’s iffy military career, Trow forecast where Rather was headed: “There are now generations growing up who are going to be reluctant to accept ‘news’ from anybody ever…[Rather] is Bad Vector Number One as to getting us to secretly (or not so secretly) dislike and distrust the authority of News Delivery…CBS should fire Dan before he kills again.” Trow’s fatal vision, which took in Rather’s breathless (and mindless) dispatches during the war in Afghanistan between Soviets and Islamists, led him to cite the “Islamic Revival”—two years before 9/11—as one of the threats “in our new more dangerous world, which really is new, and really is more dangerous.”

There’s nothing fun about being right…though that’s all that matters to most savants as Marcus once pointed out in his own critique of American commentary on 9/11. Marcus’s “Nothing New Under the Sun” wasn’t a Trovian augury; it was a polemic against mighty explainers who refused to acknowledge “something can take place in the world that never happened before…

acts that demand a whole new way of being in the world, of looking at the world, of speaking about the world. It may be the most common instinct, in the face of the new, to flee to the old: to analogies, to precursors, to whatever old name can be used to cover up the need for a new one, anything to avoid having to say “I’ve never seen anything like this before…”

Jumping off from Charles O’Brien’s sage rage at America’s “Vichy Left,”[8] Marcus came hard at avoidant know-it-alls who presented themselves as unsurprised by 9/11:

…real intellectuals admit that it is in the nature of the human condition that it will inevitably, at unpredictable times, in unpredictable ways, produce events that leave every conceptual apparatus in ruins, and…real intellectuals value nothing so much as the chance, which comes only to a few, to do their work there.

A mission statement that’s in synch with Marcus’s account of being shattered by Assumption of the Virgin.

……….

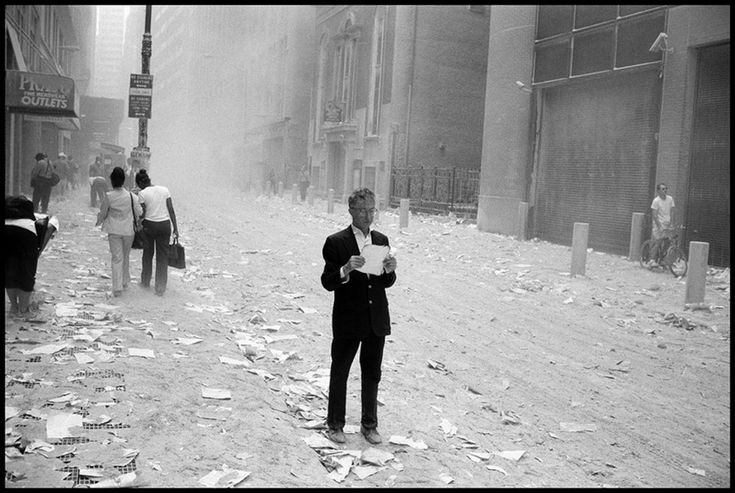

When First printed Marcus’s meditation on 9/11, the issue featured Larry Towell’s Magnum photo taken on 9/11 of a dazed man staring at a paper blown out of the towers after the attack on the World Trade Center. (Towell reported that the man stood in the road gazing at the page for a few minutes.)

I flashed back to this man in the street when Marcus went back in What Nails It to the cover image on a 50s edition of Camus’s The Rebel—a drawing that “was history to [Marcus[, it was language, it was real life as it happens…

A paper flying down the street with headlines of rebellions and refusals and battles and defeats, blowing out of reach. You can see someone chasing the sheet down the street, as if it were the last bit of written evidence of the story of its times, full of sound and fury, gone with the wind, all the assassinations, massacres, failed social experiments, poetic negations, all the raised and dashed hopes of the century that left only these illegible traces in the world, which is, somehow not nothing.

Marcus traces his own chasing back to his childhood. Marcus never knew his birth-father—the one who gave him his (rare) first name. Greil Gerstley was a naval officer who died in a horrific maritime disaster during World War Two. Marcus’s mother remarried “a San Francisco lawyer” and let the mystery surrounding her first husband grow in her son’s mind. It gave him a sense of being sui generis—“Like many children I sometimes fantasized I was not the child of my parents—but in my case it was at least half-true. Or more than half-true.” Marcus learned (over time) about the sinking of his father’s ship, “The Hull”—the story was fictionalized in Herman Wouk’s The Caine Mutiny and it has been the subject of a documentary. But long before Marcus found out resonant details about his father’s last hours, the absence of the originary Greil became a source of creative energy—“I’ve used it all my life…as an impetus.” It’s driven him to find value in what “we don’t know.”

Marcus’s fixation on the mystery of Greil Gerstley reminds me of George Trow’s ambivalent relation to his own father, which Trow seems to have used as an impetus as well, prodding him to comprehend the fall of America’s old boys club and its “aesthetic.” Trow’s books (See, in particular, My Pilgrim’s Progress: Media Studes, 1950-199tell how the country’s WASP patriarchy faded out—replaced after the 60s not by the counterculture but by a new class of symbolic capitalists presiding over a brave new world of aggregations. Trow bet America’s new social structure was pretty shaky in part because it failed to address the needs of “non-patrician descendants of the tradition of Washington”:

I’m thinking of a breakfast I had in West Virginia about three years ago. There was a West Virginian man—and I could tell from his face that this family had been here for three hundred years, and that his lineage was spread with war dead—and there had been a surprise snow storm (it was already mid-spring), and the man I’m speaking of was ecstatic, no other word can be used, because on account of that snowstorm he’s earned seventy-five dollars plowing people’s driveways. He had it in his pocket, and he showed it to me. This is the man, whatever his sins, who is deeply cultured, in American terms. He belongs to Washington. He lives in his own traditional freedom until such moment as he is told to fight for his country, and then he does, and often he dies. That’s the deal he’s made with the country. This man gives no reverence to any assumed dominant mind. As far as he’s concerned, there’s only one dominant mind in America, the one that belongs to him and Washington. Should our system of assumed dominant mind after assumed dominant mind, right on down to Real Life, which is itself based on assumed dominance of rock-and-roll, and Buddy Holly down to the Butthole Surfers—should this system of assumed dominant mind, run by people who are probably sick of the dominant mind they’re assuming, should this system run into trouble, we’re in trouble, on account of this West Virginia man.

No doubt. That’s why J.D. Vance is feeling frisky now. But perhaps we can take inspiration from a native American whose history stretches back beyond Washington. I’ve been playing “Learnin’ to Drown,” a song by Vincent Neil Emerson—an East Texan who’s proud of his Choctaw-Apache roots. “Learnin’ to Drown” might’ve come through to Trow who could hear a country song. (“Merle Haggard is a very great American.”) Marcus might go for it too since this song about orphanhood hints at odd compensations available only to sons who’ve lost fathers.

Emerson sounds like he’s been off the grid. He sings about “stealing all my meals…living in my car…

I’m barely a man and livin’ hard

My father killed himself

My mother hit the bar

Yet his “sad bastard’s song” is also a song of the open road:

Well ain’t it funny

Ain’t it funny how

The world’ll set you free

The sound of freedom isn’t in his blue bayou voice, but it’s there in the lyrics’ double-Nelson. And most of all in the melodious spray of notes at the top of “Learnin’ to Drown.” The beautiful piano/guitar/bass intro isn’t exactly country; the music seems to come from another jazzy region of Emerson’s large talent.

“Learnin’ to Drown” is just a song—not a substitute for candid democratic discourse that might help distinguish an American citizen from the idolatrous fool, the sucker, the clueless consumer, the ad person’s delight, the Trumper. Yet “Learnin’ to Drown” hints ordinary people can show and tell the truth about themselves, even if they no longer trust “the authority of News Delivery.” And it’s not a one-off. Emerson isn’t a topical songwriter, but he can sing like a citizen. His “The Man from Uvalde” images a father haunted by a school shooting:

But it just now makes no sense

Hung up on self-defense

Easier than a driver’s test

And the ammunition’s cheap

I don’t trust no talkin’ head

I don’t care if you’re blue or red

I just wanna keep my child

From dyin’ at his desk

“Gun control crap.” According to one Youtube respondent (who admitted he liked the beat). Emerson didn’t sing “The Man from Uvalde” or “Learnin’ to Drown” when he played in Brooklyn last Friday night. He took it pretty light—he and his band were the opening act, not headliners. But there was still something bracing about his amused on-stage patter—“New York City…ho-ly shit.” He seemed impressed yet unawed by the metropolis. Then he rock ‘n’ rolled right into a new song about crawfishing in Louisiana. America’s not over as long as there are new Emersons out there!

I’ll play VNE’s stuff for my son, though I’m wary about filling his ears with too much of my music. Sometimes he must wish the world would set him free from dad. Maybe that’s why he spent last summer in Mexico. At least we were on the same page—though thousands of miles apart—once we both launched into Roberto Bolaño’s great road book, Savage Detectives. I’m thinking just now of the chapter where Bolaño’s alter-ego—a writer named “Belano”—reacts to a bad review by challenging his critic to a duel. They fight it out with swords (!) on a Mexican beach…one parry leading to a near-fatal thrust. Terror, rage, embarrassment ensue, but something else is happening on the beach too, though Bolaño doesn’t disclose it right away. The swordsmen are on their way to becoming comrades for life…

Which brings me to the end of Marcus’s Kael chapter. He recalls their first encounter when Kael called him up out of the blue to bitch about his critique (in Rolling Stone) of Reeling—her mid-70s collection of New Yorker reviews. Marcus nails his story of their first back-and-forth with a Bogart reference. I didn’t get it right away. But you will if you remember Casablanca’s finish.

Notes

1 …Or “Come on in My kitchen.” Hat-tip #2 to Marcus since it was his Train, not the Stones’ version of “Love in Vain,” that brought me to King of the Delta Blues Singers.

2 I’m ashamed to recall “fine” once became my word for a week when I was teenager. God knows how I got so tony but bless my dad for demurring when I “fined” him at the dinner table. He had a job at a (relatively) posh college and he became a book reviewer who was known for having talked straight about stiffs by Big Name novelists. “Better” was never a bad word to him. But a passage from his review of a biography of Colette hints at his stance toward the culture of reflexive hierarchs:

One source of the book’s charm, no doubt, is its comparative lack of preoccupation with literary wars of reputation. Striking in social and experiential range, Colette’s life had a struggle for recognition at its core, yet she herself was free, straight to the end, of the obsession with rankings that grips many authors and most of their biographers. She cared so little, indeed, about where she finished in the prestige race that she declined to pay calls on a few lions whose backing would have assured her election as the first woman member of the French Academy.

3 Genteel John Updike didn’t care to know that jazz moved Jackson Pollock. Updike once objected to hearing Bird on Museum Guide headphones as he walked through a Pollock retrospective. Marcus isn’t a Bird-man but I doubt he’d’ve been put out by sounds of surprise at a Pollock show.

4 Though there’s no point in separating the dark from the dark in post-Millennial Morrissey.

5 Kael was too hard on Black Orpheus. As was Barack Obama who once kvetched about his late mother’s love for the flic.

6 There are bad versions of the movie floating around the internet. Here’s where you can go to find the real thing: http://realseventeenmovie.com/

7 I’ve protested in the past when Marcus has stayed on the white side of the line and I don’t want to come across as some kind of stand-in for a Race Man. So let me…whisper that Amiri Baraka doesn’t figure in Marcus’s account of Kael’s life and times, though she credited Baraka with being the first editor to publish her as Richard Torres reported in his contribution to After the Morning: Reflections on Amiri Baraka’s Legacy:

Pauline paused, laughed—she had the best laugh—and said: “You argue like Baraka.”

Startled, I asked: “Amiri Baraka?”

“Yes, he was the first to publish me when I moved to New York,” she said. “That was back when he was”—and here she deliberately elongated the sound of his name—“Lee Royyyyy Jooones.”

8 From O’Brien’s “The War”:

On September 11…

The Vichy Left knew immediately what was necessary. We all needed to have them explain the thing to us. Unfazed, hardly missing a beat, in this time of emergency, they stood prepared to serve up, again, the same mess, again, they had served up, again, only a day before. The standard pitch opened with a ringing – but quick – deploring of the event: ringing, because these gentlemen and ladies of a fancied left habitually talk in such tones (and because, allow them this, their hands really are spotless); and quick, because they had some serious self-congratulation on their minds. It is telling that before getting to the meat of their arguments, they didn’t pause to note a thing that was clear to most people: that September 11 also witnessed a great deal of heroism, most obviously the hundreds who sacrificed their lives to save many thousands of others. There were to be no distractions from, in Edward Said’s loathsome phrase, “this community of conscience and understanding”, secure in the consciousness of its own virtue, snug and smug.

Marcus has a rich history with Charles O’Brien’s writing. Back in 1989, he steered readers to O’Brien’s first published piece on the politics of pop music and in 2005 he talked up O’Brien’s “Play Fuckin’ Loud.”