Freeman Hrabowski III grew up in Birmingham when it was known as the most segregated city in America, but he realized early he was born free to learn. (“Heaven for me was eating my grandmother’s blueberry pie and doing math problems.”) Hrabowski’s parents and grandparents passed down the idea that education might be an end-in-itself even if black people in the South didn’t have the luxury to conceive of “pure” learning at odds with economism. Hrabowski remains a realist when it comes to schooling. He knows culture don’t butter no bread. So, he’s become the foremost proponent of STEM education for black college students by building a scholarly vehicle for upward mobility—a research university that feels homey to kids in black communities who love learning math as much he did.

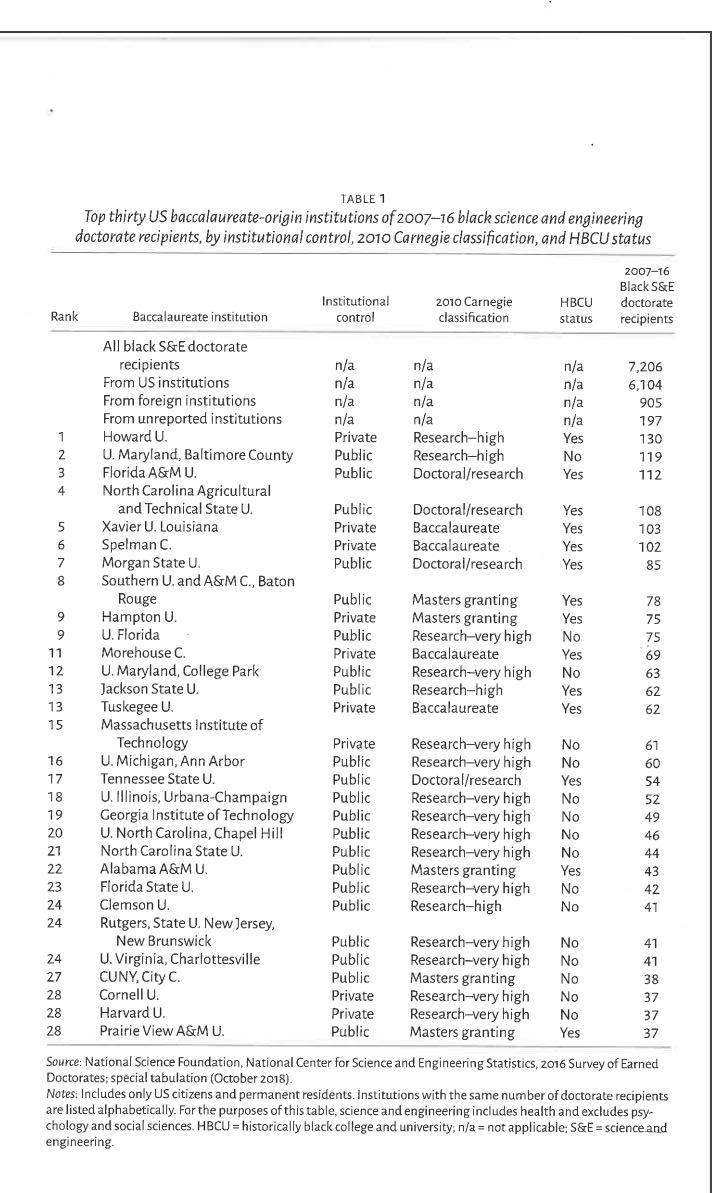

Hrabowski retired in 2022 after thirty years as president of the University of Maryland of Baltimore Country (UMBC)—a school with a less than toney pedigree that under his aegis has been the “baccalaureate-origin” institution for hundreds of black Ph.D.’s in natural sciences, math, and engineering. Scores more than have been formed by Ivies—or any other elite, predominantly white institution—in recent decades. UMBC’s major competition on this front has come from HBCUs, though the percentage of African Americans in its student population tends to hover around 15%. UMBC’s progress in STEM education for minorities is due chiefly to the Meyerhoff Scholars program, which was endowed in the late 80s by Baltimore philanthropist Robert Meyerhoff who was out to break down broadscale bias against young black males. Due to court rulings, pressure from feds, etc., the program is no longer a diversity-only thing. About 30% of the current class of Meyerhoff Scholars now belong to groups that have not been “historically underrepresented” in the natural sciences, but affirmative action still drives the program. “Meyerhoff By the Numbers” on UMBC’s website tells the tale.[1] The following table, though, from a National Science Report might be even more absorbing. It’s featured in The Empowered University (2019), —a text Hrabowski wrote along with UMBC collaborators Philip Rous and Peter Henderson.

I don’t mean to seem trifling—this is serious biz—but it’s something of a hoot that UMBC is the only PWI (predominantly white institution) near the top of the table, which is dominated by HBCUs, while Ivies like Harvard are down at the bottom next to a U. in one of our great prairie states.[2]

Hrabowski isn’t one to rub it in. (One of The Empowered University’s blurbs comes from a president emerita of Harvard.) He knows UMBC needs benefactors—“A day without an Ask is like a day without sunshine.”—and he’s got better things to do with his time than rag on potential donors. He tells at least one story, though, that hints his instinct to offer white people opportunities to give back hasn’t always trumped his desire for payback. When he graduated from Hampton Institute and went on to graduate school as a flyboy in University of Illinois’s buttermilk during the 70s, Hrabowski ran into a snotty professor who once…

wrote a proof on the board, moving directly from step one to step five with no explanation of steps two, three, and four. I did not see how he arrived at step five. I had been accustomed, as an undergraduate at a liberal arts college, to ask questions in class, so I asked, “I can get to steps two and three, even four, but how did you get to step five?” He looked at me and said with a smirk, “Isn’t it obvious?” Everyone in the class smirked as well. I thought, “If it were obvious, I wouldn’t have asked you the question.”

Hrabowski never asked another one in class, but that wasn’t the end of it. He acted on advice he’d gotten from his HBCU profs at Hampton: “Be humble, and say: ‘I need your help.’” He “politely bugged” Professor Smirk over and over again, squeezing him for everything he was worth outside of class.

When the midterm papers were later handed back to us, I looked around and saw several Cs—a flunking grade in graduate school—while I had earned an A minus. I held my paper up and said, “I guess it was kind of obvious.”

Hrabowski may have given himself to permission to gloat once, but he has a history of resisting what he calls the “cutthroat” culture in science and math. His career as an academic administrator has been shaped by his resolve to change that culture.

As a college freshman in 1966, I remember the convocation speaker saying to our class, “Look to your left; look to your right; one of you will not graduate. At UMBC, we say, “Look to your left; look to your right; our goal is to make every one of you graduate. If you don’t—we’ve failed and we’re not planning to fail.”

Hrabowski has sought to make UMBC over into a place where students support each other, and teachers foster collaborative work. The Meyerhoff program, for example, starts cultivating intra-cohort solidarity and group problem-solving the summer before incoming freshmen enter UMBC. Newbies find out fast what it means to join a true community of learners. (Meyerhoff Scholars live together on campus during their freshman year.) No doubt that’s one reason why they’re five times more likely “to have graduated from or be currently attending a STEM Ph.D. or M.D./Ph.D. program than those students who were invited to join the program but declined and attended another university.”

Hrabowski talks up his program’s results without buying into the idea higher ed is a game that must have winners and losers.

From “weed-out courses” to “grading on the curve,” our structural concepts say that not all of our students—who have met our admissions standards, by the way—will succeed, much less excel. It’s a language that pits faculty against students and students against one another, rather than creating a community of learners. We have to change that thinking…

Hrabowski began looking for new templates before he made his pitch to Robert Meyerhoff in 1988 and got the chance to implement their joint initiative. He hoped to find useful models at other “predominantly white institutions that were successful in supporting black students in an intentional way in the natural sciences and put them on a path to graduate school.” But. “There weren’t any…” He often recurs to the moment in the late 80s when he realized his school would have to find its own way and there’s another marker-year that tends to come up when he tells the story of the STEM at UMBC. In the summer of 2002, the journal of American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (ASBMB) noted something was jumping at UMBC…

Out of sixty-six chemistry and biochemistry degrees awarded to African American students nationwide that year, UMBC had awarded twenty-one of them, well ahead of any institution of any type.

UMBC’s track record has become more and more undeniable in this century and the University (and Hrabowski) have drawn plenty of attention in the Academy[3] and even in the political world. Obama made Hrabowski the Chair of a Presidential Commission on Educational Excellence for African Americans. His best pol tale, though, dates to 1992 when he was still interim president at UMBC. Back then he invited the governor of Maryland, William Donald Schaefer, up on the roof of UMBC’s Administration building where they looked over the campus and Hrabowski described what he hoped to see there in the future. The governor dug the projections and told the young visionary he’d press the institution’s Board of Regents to appoint Hrabowski president right away. Hrabowski said “NO!…sir,” since he didn’t want colleagues or students to think he’d gotten the job through political patronage…

[W]hen I politely declined his offer to intercede on my behalf, he then asked what he could do, noting that he didn’t have a lot of money to throw around. I said, “Give me trees!” After he left, he called the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and asked them to plant trees all over campus. Those trees are now 25 years old, and they have brought much beauty to our campus, literally and visually making this a different place.

UMBC’s flourishing has been noticed by journos in mainline media. Hrabowski has been profiled on Sixty Minutes. Just last season, the Times’ John McWhorter invoked UMBC’s record of producing STEM grads. I was glad McWhorter was on the case. He’s right to suggest UMBC’s approach to STEM ed aligns with his own sense “the general theme” among black educators should be that “Black people can meet standards that other groups are meeting”: “The question shouldn’t be whether the standards themselves are appropriate.” I’m sorry to report, though, McWhorter downplays Hrabowski’s clarity about the need for transformative changes in America’s educational system. (See Hrabowski’s letter here to Congress here on behalf of The National Alliance, “We the People—Math Literacy for All.”) Nor does McWhorter seem to share Hrabowski’s awareness that a black student’s sense of self may be eroded by stubborn stereotypes ingrained in the country’s caste/class structure.[4]

McWhorter’s ender confirms he isn’t entirely in synch with Hrabowski. He signs off with nods to Shelby Steele and his “classic” The Content of Our Character: A New Vision of Race in America. Hrabowski has been known to cite a writer in the family Steele too. But it’s not Shelby. Hrabowski has invoked the work of Claude Steele (Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do) whose analysis of the ongoing “threat” of racial (and other) stereotypes is directly opposed to the history-less piffle that made his twin brother famous in the early 90s.[5] Back in that day, Shelby Steele was part of a crew of black neo-conservative spokesmen who gave readers who wished to be done with race an out. Steele et al. provided a soothing answer to the question of why many black Americans had made only halting progress despite increased opportunities in the post-civil rights era. The basic problem, according to Shelby Steele, wasn’t the intellectual and educational and socioeconomic deficit piled up during centuries of absolute race stratification. It was, instead, the fathomable but nevertheless not finally benign disposition of soft-headed white Americans to spoil their black brothers and sisters rotten.

In the early 90s, when Steele was trashing affirmative action programs, Hrabowski was inventing the most successful one in the history of STEM education. I’m reminded of how Steele got loud about being a shirker in his youth. (He claimed he’d made a habit of guilting white people who tried to help educate him.) Meanwhile Hrabowski was teaching diligent black scholarship boys to trust themselves and resist stereotypes that made it hard for them to fully take in what they’d already achieved and what they might do in the future. Steele’s “new vision of race in America” all but erased the strivings of kids in the first Meyerhoff cohorts.

In his memoir, Holding Fast to Dreams: Empowering Youth from the Civil Rights Crusade to STEM Achievement, Hrabowski remembers how those kids didn’t want to take it to the stage (unlike Shelby Steele who’s always been up for close-ups though he’s never been all that crisp on tv)[6]:

At one point…we asked each student to walk up onto a stage and talk about himself: his name, where he was from, one achievement of which he was particularly proud, and his dream. As each student came across the stage, not one of them mentioned an academic achievement…

Hrabowski realized what was happening and insisted they stop talking about their experiences in the band or on the wrestling team. He told the new Meyerhoff Scholars to go back and tell the room about their academic deeds.

The first young man to return to the stage attended Baltimore Polytechnic Institute…At the time, Poly—as it is familiarly known—still had many middle-class white students, and the student said he was about to become valedictorian. He came across the stage and said, with embarrassment. “I have never made a B.” He had his head down. And it hit me. I said, “Boy, come back here.” Then I said to the whole group. “Do you understand what he’s telling you? This young man is telling you he has earned A’s all his life.” I turned back to the young man and said, “Son, let me tell you something. You’re more special than you realize. I want you to say your name, and I want you to shout it out that you are a straight A student.” He was still too quiet that second time, and so I said, “Say it again.” The third time he shouted it out, and the room erupted—all of the visiting students and their families gave him a standing ovation. There were tears. It was a revelation.

Hrabowski’s apprehension that “we, as a society” were not getting black children “excited about being smart” contrasts with Shelby Steele’s insistence that society owes black kids nothing:

Blacks must be responsible for actualizing their own lives…The responsible person knows that the quality of his life is something that he will have to make inside the limits of his fate…He can choose and act, and choose and act again, without illusion. He can create himself and make himself felt in the world. Such a person has power.

Such faux-Overman fustian is so far gone from Martin Luther King’s “beloved community” in struggle. It was shameless of Steele to invoke King’s content. Freeman Hrabowski, by contrast, has every right to place UMBC’s communities of learners in the tradition of King and the Civil Rights Movement.

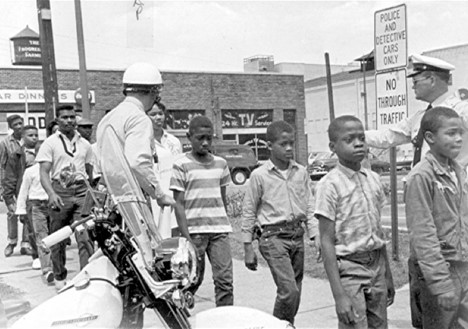

Hrabowski actually participated as a 12-year-old in the 1963 Birmingham Children’s March. He’s second from the left in this AP photo of a line of children being led to jail in Birmingham on May 4th 1963.

(AP photo/Bill Hudson)

Hrabowski’s Holding Fast to Dreams includes his own harrowing notes from a Birmingham jail. His trip to that jail (and his life’s journey?) began when he went with his family to their Birmingham church for a mid-week mass meeting. Hrabowski hadn’t wanted to go. His parents placated him by letting him eat M&Ms and do his math homework in the back of the room. He was working on algebra problems when a speaker caught his ear.

We were accustomed at our church to impressive speakers, but this man combined polish with a message I could not ignore. We knew that blacks were not treated fairly by those in power but we tended to think, “This is the way of the world.” In contrast, this man was saying that the world could change and that even the children could have an impact on what might happen to us in the future. In fact, he was saying that our actions were needed and mattered. I was impressed. I asked my parents, “Who is that man?” It was the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.[7]

That account is from Holding Fast to Dreams, but Hrabowski gives the story an even more personal tinge in a 2011 interview. (“King? That’s his name?”) There he tells how King’s ideal of integration spoke directly to him because it meant Hrabowski might be able to “find out just how smart these white kids were.” He smilingly recalls how he didn’t “believe anyone was smarter than I was.” And then he qualifies that statement in a way that distances him from “gifted and talented” progeny of urban haute bourgeois.

Smart wasn’t about what you were born with. It was about how hard you were willing to work. My parents had to punish me sometimes for not going to sleep. I just wanted to keep working and they were worried I was working too hard. To me that was smart. When you worked really hard and you achieved a lot and you got A’s not because you wanted grades but because you… dared to know.

Hrabowski makes it clear that he wasn’t a brave-heart when it came to physical face-offs. While he pressed his parents to let him march during the Birmingham Children’s Crusade, he began to get really scared when they said yes (after first turning him down and then praying on it for a night). His fears didn’t lessen during the run-up to the march, though he was well-prepped by the Movement’s organizers. Hrabowski was made a leader of one of the batches of children who set out to pray for equal justice on the steps of City Hall. His small group made it all the way to their destination…

I can’t tell you how my knees were shaking as I arrived at the steps of City Hall. And who was there but Bull Connor himself…An imposing man with a booming voice, he was obviously angry on the day of the march because of the TV cameras. He looked at me and said, “What do you want, little Nigra.” Remember, I was not a courageous kid. I looked up at him, scared and managed to say in my Birmingham accent, “Suh, we want to kneel and pray.” He spat in my face. Then my fellow demonstrators and I were gathered up and shoved into a police wagon waiting nearby.

Hrabowski’s account of what happened next complicates any exultant version of the Children’s Crusade. Not that it’s wrong to evoke thrills that came when a younger generation broke the barrier of fear in the Jim Crow South.[8] Hrabowski, though, isn’t in triumphal mode when he goes back to Birmingham in his head: “Being in jail was an awful experience.” He doesn’t linger over his horrific five days in May, but he recalls how cops set “bad boys”—juvenile offenders imprisoned before the march—against jailed protestors. “Unspeakable” things happened. Hrabowski got some help from a bad boy who’d been an elementary school student of his mother’s. And he sometimes managed to keep wolves away by having his group recite bible passages when they felt threatened: “Every time I read from the bible, the bad boys would retreat: they didn’t want to fight with God.”[9]

King and parents of the imprisoned children managed to give him comfort too when they rallied outside the jail. But being encaged was traumatic for Hrabowski. And the ordeal wasn’t over when he and the rest of the protestors got out of jail. A-student Hrabowski, who lived large in classrooms, was distraught when he learned they’d all been kicked out of school, though his principal eased the minds of the banned boys—at the risk of losing of his own job—by holding an assembly where the suspended kids were treated as heroes not pariahs. Before the next school year, the courts would reinstate Hrabowski and other students whose protests delegitimized segregation. Things seemed to be looking up. Then came the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church. Hrabowski does more than point at sequels. (Though that alone would be a fearsome corrective to versions of American history that imply it was a smooth ride once King gave his Dream speech at the March on Washington in the summer of ‘63.) 16th Street Baptist Church was the sister church to the one Hrabowski attended with his family. He had relatives and friends at 16th Street including…

Cynthia Wesley, a classmate who’d always treated me well. It was devastating to learn that Cynthia and three other girls had been killed. I had seen Cynthia just the Friday before, and I remember her saying as we left school that day, “Bye, Freeman. See you Monday.” I’ll never forget that moment—the kindness and hope in her eyes. Another of the girls had been given a ring that morning by her father. We heard that they had found her hand before they found her body. My friends and I had nightmares for years. It was as if we were in a war.

The struggle made him as tough as “crucible steel” (to borrow King’s phrase). It also ended up giving him a sharp angle on his own and others’ paths through life. What he learned, with help from elders who tried to make sure he wouldn’t let hatred eat him up from inside, was that neither he nor his worst enemies were unconditioned, unencumbered, uncircumscribed actors. Hrabowski makes an audacious move in Holding Fast to Dreams, linking his own makings as a member of a black middle-class community bred for achievement with the inuring of Bull Conner. (“He was somebody’s child,” as Hrabowski’s own mother averred on the day Bull died.) Hrabowski isn’t locked on the past. He knows Bull Connor’s brutalism might be out of time now (notwithstanding Trump’s demon seed), but he points out plenty of white Americans still grow up with negative expectations about minorities and women—biases that shape hiring practices and life-chances.

I once worried that Hrabowski’s own impulse to uphold high expectations for black students might’ve put him at odds with the late Bob Moses—another proponent of math education who had deep roots in the Civil Rights Movement. My agita was due to Hrabowski’s Talented Tenth-ish focus on graduate ed whereas Moses’ “radical equations” challenged America’s entire system of schooling and its class-bound meritocracy. I worried needlessly. Holding Fast to Dreams ends with Hrabowski hugging Moses—“a civil rights leader, eminent scholar, and one of my heroes”:

He has developed a brilliant philosophy that holds that mathematics education is nothing short of a civil right. He has dedicated his career to the Algebra Project, based on that conviction. “Mathematics literacy in today’s information age,” he has written, “is as important to educational access and citizenship for inner city and rural poor middle and high school students as the right to vote was to political access and citizenship for sharecroppers and day laborers in Mississippi in the 1960s.”

Hrabowski praises Moses for finding ways of relating math to students’ lives, to their physical environments, to what’s most important to them.

We need to bring that level of creativity to mathematics in K-12 and beyond if we are to ensure that many more people of color and women succeed…The question we must ask ourselves is, do we really believe that if given the proper support, students from all backgrounds and races can truly succeed. You know my answer is yes.

That was Moses’s answer to Holding Fast to Dreams. Moses—permanent rebel and natural-born outsider—made common cause with a younger man who’s spent most of his life as a college president. And you can tell the elder’s impellent blurb wasn’t about logrolling:

Dr. Hrabowski speaks to a twenty-first-century America, addressing Lincoln’s “House Divided” conundrum. “If we could first know where we are and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do and how to do it.” Get the book. Read all about it.

Trust Moses (and Abraham).[10]

Notes

[1] From “Meyerhoff By the Numbers”:

- Alumni from the program have earned 403 Ph.D.s, which includes 71 M.D./Ph.D.s, 1 DDS/Ph.D., and 1 D.V.M./Ph.D. Our graduates have also earned over 155 M.D. or D.O. degrees, as well as over 320 master’s degrees, primarily in engineering, and computer science and related areas. Meyerhoff graduates have received these degrees from such institutions as Harvard, Stanford, Duke, M.I.T., Berkeley, University of Michigan, Yale, Georgia Tech, Johns Hopkins, Carnegie Mellon, Rice, University of Pittsburgh, NYU, and the University of Maryland.

- 49 alumni currently hold faculty appointments at universities like Duke University, University of Michigan, Stanford University, Johns Hopkins University, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

- Over 300 alumni are currently enrolled in graduate and professional degree programs.

- An additional 245 students are currently enrolled in the program for the 2022-2023 academic year, of whom 69% are from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups and 31% are from non-underrepresented racial and ethnic groups.

[2] Pace FDR.

[3] That attention has not moved elite institutions to replicate the Meyerhoff Scholars program. (There are a couple of state schools that are trying to do it the UMBC way.) Administrators at Ivies et al. seem content to praise Hrabowski. Maybe they’re put off by the optics of a high-style University copying a provincial U’s approach to STEM education.

[4] Though McWhorter is worried woke projections of black victimhood might convince his daughters they can “best make their careers by claiming exceptional vulnerability and fragility.” Per Fredric Smoler’s strong defense of McWorter’s role as a dissenter from race-based pieties of leftist “electists” (McWhorter’s Rare Dare – First of the Month). Smoler is right to point out McWhorter’s contempt for cancel culture isn’t a sign he’s a man of the right, Yet McWhorter’s bow to Steele’s “classic” hints there’s a certain willed blankness near the core of his contrarianism. Is McWhorter unaware Steele is a paid-in-full, right-wing argufier who regularly makes nice on Fox with ranters like Mark Levin?

[5] The Steele twins have been characterized as “ideological opposites.” A phrase that seems to miss the essence of their differences. In a letter to the Times, Claude Steele once tried to distinguish his own concept of “stereotype vulnerability, or threat” from his brother’s “concept of racial vulnerability,” which he linked with the “victim-blaming, ‘ethnic self-hatred’ theories of the 1940’s and 50’s (e.g., those of Kurt Lewin, Erik Erikson, Gordon Allport).” The final paragraphs of Claude Steele’s letter hint at why it’s wrong to reduce the intellectual conflict between the Steeles to ideology.

This research shows how stereotype threat powerfully affects these groups. It is from this research that my policy position on college affirmative action comes: effective affirmative action, like effective school integration, is dependent on how it is implemented.

By offering challenging work and having high expectations (not hand-holding), our program at the University of Michigan helps black and white students achieve. This shows that such a program is possible in a context of affirmative action. This is fact, not ideology.

[6] Shelby Steele isn’t satisfied with Fox News facetime. He’s the main talking head in a tendentious anti-BLM documentary (made with his son), What Killed Michael Brown?

[7] For the record, Hrabowski doesn’t slight James Bevel, the great organizer who convinced King to call for the Birmingham Children’s Crusade.

[8] Their group high, soundtracked by Sixties R&B and Movement songs, is all up on the screen in the wondrous documentary Mighty Times.

[9] Hrabowski brings up class divisions within Birmingham’s black community. He was one of the few black middle-class kids who participated fully in the Children’s Crusade. He’s not into invidious comparisons on this front. His age-mate Condi Rice may not have marched with him, but her father was one of his role models at school. Rev. Rice was a subtle fellow: “He was the first person to teach me that it was possible to make a joke…without so much as a smile.”

[10] A friend pointed out that Hrabowski and Moses shared “name issues.” Moses got so sick of leader-mongering spins on his last name that he started using his middle name and calling himself Robert Paris. Freeman (not Freedman) was the third Hrabowski born after slavery. Hrabowski was the name of an ancestor who was a Polish-American slaveholder in the South. Freeman recalls his father had a heavy foot when he drove; Southern cops who’d stop his pop would often assume he was a foreigner since he had light skin, “good hair,” etc. They’d tend to let him off with a warning unless young Freeman was in the front seat with his nappy head. Then dad would have to pay the ticket.