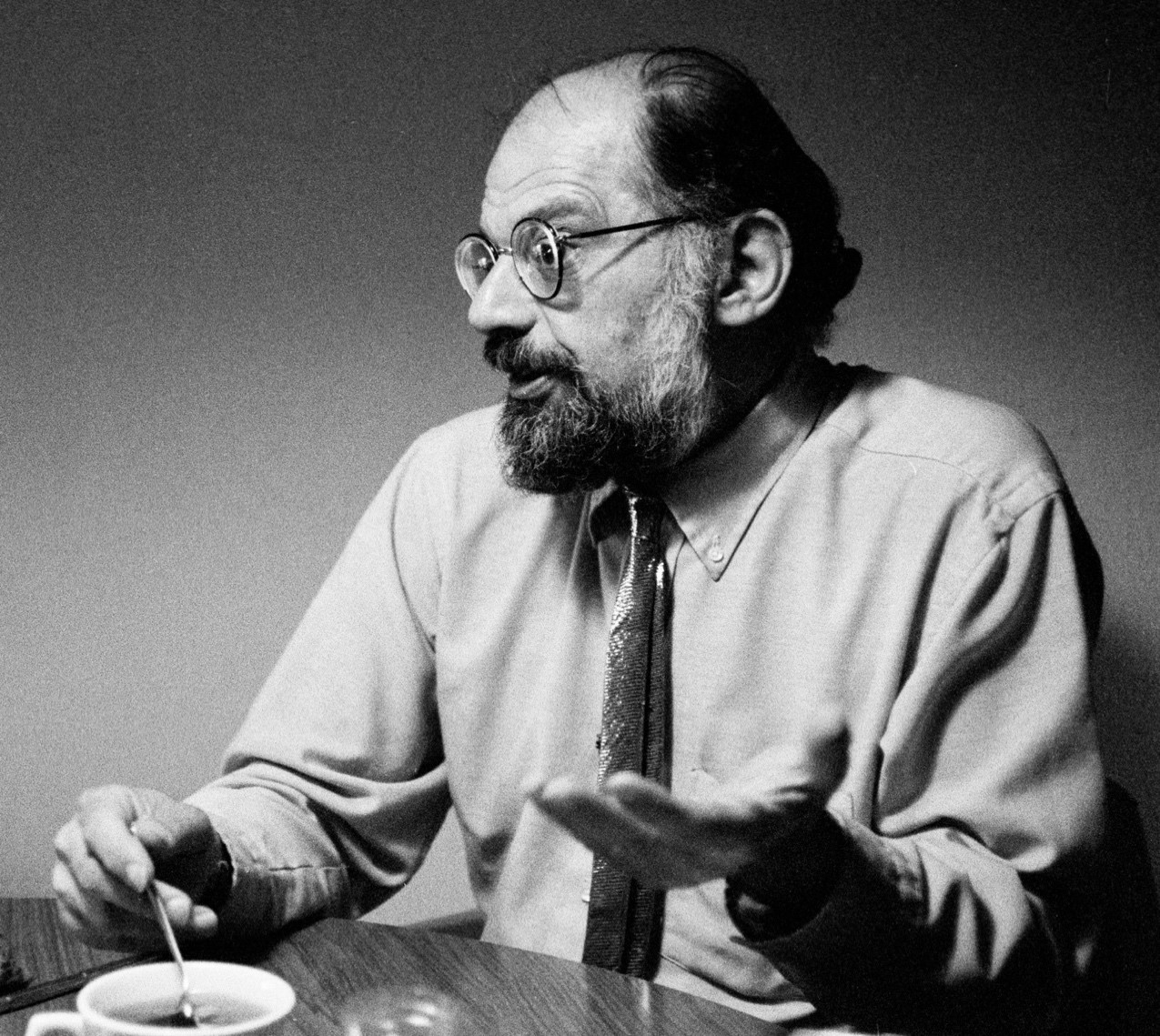

Every time I saw Allen Ginsberg, he picked up our conversation where we’d left it last time, no matter how much time had intervened. At a 1990 poetry reading, he said, “I saw your friend.” “Which friend?” I said. “The one we were talking about.” We hadn’t seen one another since the day I took this picture, six years earlier. He and Diane Christian had a running conversation about Blake that went on for twenty years. He would just pick it up where it had stopped last time, as if it had been a conversation paused so someone could refill a glass or go to the john.

We’d met at a drug conference at the University of Buffalo in spring 1968. Abbie Hoffman was there, and so were Jerry Rubin and Hugh Romney (a.k.a. Wavy Gravy) and the Merry Pranksters; there were researchers and political people; there were musicians and writers. Even Tim Leary was there: he sat on stage in a full lotus and free-associated while his young wife Rosemary tried to keep their infant son from being too disruptive. Leary kept losing his train of thought and Rosemary whispered in his ear or people in the audience yelled out cues to get him going again. One time he paused and didn’t even seem to be missing the train: he just grinned loopily out at the world. After a while someone yelled, “So what’s the name of Rosemary’s baby?” Leary furrowed his brow, not remembering that either, grinned as if he’d figured something out, then took off on an entirely new tack.

After one of the panels, Mike Aldrich, the organizer of the conference, asked me to drive Allen, Peter Orlovsky, and San Francisco psychiatrist Tod Mikuriya to a party for the participants at Leslie Fiedler’s house. When we were in the car, Allen said he had to stop at the motel to make a phone call. “Make it from Fiedler’s why don’t you?” Orlovsky said. Allen said the call was to a Playboy editor about his upcoming Playboy Interview; he had to look at the page proofs, which were in the room. When we got there, he said it might take a few minutes, so we had all better come on up.

We all took off our coats. Allen found the big Playboy envelope, he looked over the pages and he made his call. We all put on our coats, we got to the door, Orlovsky opened the door, and that was when Allen said to the psychiatrist, “What’s your name again?”

“Tod Mikuriya.”

“Tod Mikuriya. That’s an odd name,” Allen said. “Where does it come from?”

“My mother was German; my father was Japanese.”

“Mik-ur-ee-ya.” Allen’s intonation requested translation.

“It means ‘of the royal kitchen’ or something close to that. I guess some ancestors on my father’s side were officials on the emperor’s staff or maybe they washed pots in his kitchen.”

“And Tod is ‘death’ in German,” Allen said.

“Yes. It’s ‘death’ in German.

” So your parents named you ‘death in the royal kitchen.’ What a burden that must have been to grow up with.”

It was a long moment before Mikuriya responded. Then he started to talk. He talked faster and faster: words spilled out, poured out, came out so fast they seemed to be pushed out by the words in queue behind them.

Many of us have bits about our names. Descendants of East European Jews like me have explanations about how we got the anything-but-East-European names we now bear. I once heard the Very WASP John Updike say, immediately after being introduced to Ipswich neighbors he hadn’t met before, “I suppose you’re wondering about my name. It has a very long….”

But that’s not what Tod Mikuriya was doing that night in the University Manor Motel in Buffalo, New York. He was doing something he’d never had the occasion to do before. I don’t know if he’d even done it with himself in the privacy of his own brain.

Allen sat on one of the beds and he motioned Mikuriya to sit on the other. They faced one another, their feet maybe a foot apart. Orlovsky, my wife and I stood near the door, still unsure of what was going on. The it became clear that Allen was not going to interrupt Mikuriya; it was equally clear that Mikuriya was going to keep talking until he was done. The three of us took off our coats and found places to sit.

Allen listened to Mikuriya with eloquent intensity. It was real, it was sincere, it was total, and it was, I’m certain, something Mikuriya had never experienced before in his life. I surely hadn’t.

I have no idea how long he talked. He talked until he came to terms with being named Death In the Royal Kitchen, he talked until he was shriven, until he said what he’d needed to say for so long and had never, until that moment found a place where and a person to whom it was safe to say it. During all of that astonishing monolog, Allen never gave one sign of disinterest, impatience, party-lust. It was like one of those movies or a play where two people are talking and the lights on everyone else in the room fade to just this side of darkness. They’re there, those other people, but they’re not moving, they’re not making a sound, and they’re irrelevant.

When Tod was done Allen got up and said, “Let’s go to Leslie’s house,” which we did. When we got there, someone said, “We were all wondering what happened to you” and Allen said, “We got to talking,” and no more was said of it.

The last time I saw Alan was at the memorial for Bill Kunstler at St. John the Divine in November 1995. He performed his wonderful poem “Skeletons,” which he’d performed at UB’s FiedlerFest six months earlier. We got to tallying other friends and acquaintances dead and gone, among whom were Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, and that got us back to the 1969 drug conference in Buffalo. I asked him if he remembered that evening when Todd Mikuriya came to terms with his name. “Oh yes,” he said, “very well. And later I had a good conversation with Leslie about Shakespeare and afterwards some of us went out. You weren’t with us.”

“No, I wasn’t.”

“I didn’t think so. Well, it was a good time.” So it was. A good long time.

Excerpted with permission from Changing Tense: Thirty memento mori by Bruce Jackson, published by BlazeVOX.