CNN fired a photojournalist who was embraced by the leader of Hamas.

Like many Jews, I’ve read things about the bombing of Gaza, seen things on TV, and heard things shrieked in the streets that have horrified me in starkly contradictory ways. The truth about this awful sequence of events is as hard to come by as it is complex, but the slogans mask as much as they proclaim, and the coverage does something even more ominous: it simplifies. Every day I’m glued to my TV, gripped not just by the unbearable images that the carnage has produced, but also by the stimulation of my senses, the spectacle of mass death. It’s what I’d call visceral news, which compels me to watch, and it’s all true. But it’s not the truth. That requires context, which isn’t a visual.

The difference between civilians and Hamas fighters in mufti is so tricky that 20 percent of Israeli casualties are caused by friendly fire, but that’s not something video can convey. I can’t see that Western journalists only enter Gaza with the Israeli military, which means that the media must use freelancers, many of them locals who may be part of the Palestinian struggle. (CNN fired one photojournalist after they found a picture of him being embraced by the leader of Hamas.) I can’t see that tallies of the dead include thousands of fallen fighters along with women and children. I can’t watch the ways in which both Egypt and Israel trap people in the Strip. I’m dependent on the narrative, which varies enormously depending on which publications, networks, and online posts I choose. The consensus that forms from these sources can’t convey the ways in which trauma breeds vengeance and terror on both sides.

To understand these complications, I have to rely on poetry, and I’ve been reading a lot of it lately. Here’s what W.H. Auden wrote on the eve of World War Two, far more eloquently than any news report:

The error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.

This is not a justification for what Israel has done in Gaza—there is no justification. But, as Auden knew, “those to whom evil is done do evil in return.” In other words, it’s complicated. Reporting on the ground is not.

Unless they are scrupulous, most journalists pay attention to what affirms their hunches, and so do most readers and viewers. If you believe that Israel is a genocidal state, you’ll have plenty of proof in the slaughter on daily display. If you think that Hamas is a ruthless terrorist group, you’ll have ample evidence in the ordeal of the hostages and the strong likelihood that Hamas fighters committed what The New York Times called “a pattern of rape, mutilation, and extreme brutality against women.” But there are hardly any images of those assaults, and only a few eyewitness accounts, which can be contested—and are, by those who think the violations of human rights that launched this war are a fabrication. Every aspect of this story has a long history with tunnels of its own, but they remain underground, while the surface explodes.

So, today, I want to write about the context that’s missing from much of the coverage. I’ll begin with the charge that Israel has committed genocide, presented at the World Court by South Africa. I’ve seen many AI-generated images of Zulu warriors leading a Palestinian child to safety. I’ve read a number of “think pieces” that reiterate the South African complaint point by point, while omitting the 400-page Israeli response. I’ve had to dig deeply in order to discover that, though this charge stems from the destruction in Gaza, it also reflects the long, tangled relationship between South Africa’s government and Israel.

Where was South Africa when a million Rwandans were hacked to death by machetes? According to Reuters, they merely delivered a “diplomatic slap” to the Rwandan government. When China enslaved the Uighurs and invaded Tibet, sending thousands of Han Chinese settlers, did South Africa complain to the World Court? China is South Africa’s biggest trading partner, so you can guess the answer. This doesn’t invalidate their case, but it does provide a geopolitical setting for a government that has much to gain from assuming the role it has, especially since the South African economy is floundering. Their legal team is certainly not motivated by anti-Semitism, but anti-Semites were among their guests. Jean-Luc Melanchon, the French leftist presidential candidate who recently accused the Jews of killing “one of their own” (i.e. Jesus) was present at the hearing, along with Jeremy Corbyn, former head of the British Labor Party, who presided over an anti-Semitic scandal so divisive that it may have cost his party the last election. None of this was part of the dominant media narrative, but it is part of the story.

*********

One of the most important rules in journalism is the obligation to give anyone attacked a fair chance to respond. But in the coverage of Gaza, that principle has often been ignored or given short shrift. British broadcasters are especially sloppy when it comes to contacting the Israelis, and if an official is brave enough to appear on a show, that person is harangued with such venom that they can’t really make their case. On the PBS News Hour I recently watched an ITV clip from Britain about a group of Gazan men carrying a white flag, who were shot at by Israeli troops, killing one of them. I saw the dead man’s widow wailing over his body, and I cried. But it was left to the PBS anchor to seek a response from Israel, and it involved a claim, from examining the sound of the bullets, that they weren’t part of the Israeli arsenal. I don’t know if that’s true, but it presented a potentially complicating factor. The broadcasters at ITV felt no such need. And they are not alone.

Something truly nasty is going on in Britain, where attacks and insults against Jews rose last year by an estimated 500 percent. British students are responsible for some of the rhetoric American protesters have used, including the latest derogatory term for Jews—Zios—that inspired the chant at some U.S. universities, “Zios off campus.” One Jewish student at Oxford University wrote, in a piece for The New York Times, that mezuzahs were being ripped from dormitory doors. The Forward, a Jewish publication with some of the best coverage of this crisis, reports that three Israeli tourists were targeted by a group of men and beaten in the middle of London’s entertainment district; the police took half an hour to respond, despite repeated calls. This is not the first attack on Jews in Britain. A notorious incident occurred in 2021, when a busload of Hasidic Jews celebrating Hanukah was waylaid by a crowd pounding on the vehicle. The BBC reported on that episode, claiming that the Jews had hurled an anti-Muslim slur at their attackers. But the British agency that regulates media berated the BBC for ignoring evidence that the victims were calling for help in Hebrew. The BBC also reported that the Israeli army was targeting Gazan medical teams, when they were actually delivering supplies, and the network erroneously claimed that the Israelis had bombed Al-Ahli hospital. “It’s hard to see what else it could be,” the anchor said, though the incident was probably caused by a defective Hamas rocket. One veteran BBC broadcaster resigned,“citing a “culture of low-grade anti-Semitism that is present throughout the entire organization.”

The BBC’s coverage of Gaza is the most stilted I have seen, and that may have as much to do with demographics as it does with bias. The BBC is the most popular broadcasting news organization in the world, reaching more than 300 million people every week, some 42 million of them Arabic-speaking. The size of its audience in Islamic nations, not to mention the large Muslim population of Britain, may have something to do with the BBC’s decision to identify Hamas fighters as militants rather than terrorists, even though the T-word has been used to describe IRA bombers as well as Al-Qaeda. Demography matters, especially to a company that has lost about a third of its income, according to the Financial Times. It must mean a great deal what a substantial Muslim audience thinks of the way it is covering this war.

But it’s also true that anti-Semitic assumptions have deep roots in British culture—you can read all about the Blood Libel in The Canterbury Tales. Tropes about Jews lurk under the surface of awareness, as was the case with a cartoonist at The Guardian who portrayed Israel as an octopus. The Guardian apologized for the cartoon and didn’t renew the artist’s contract, but he was stunned to discover the subtext of what he’d drawn. The Jew as an octopus with tentacles encircling the globe is a notorious Nazi image. This image is so imbedded that, apparently, it can be unintentional.

If this is simply anti-Zionism, you are probably convinced that Hamas is not a fundamentalist force which committed systemic rape during the rampage of October 7. Katha Pollitt’s much-discussed piece in The Nation asserts that a number of feminist groups have been slow to confront this outburst of sexual violence, and I’ll add that some bloggers whose main subject is sexism have said nothing at all. A social-media post cited by Pollitt is an extreme version of this obliviousness; the writer demands testimony from the “purported rape victims,” even though they are dead. Pollitt also interrogates the slogan “Palestinian liberation is queer liberation,” pointing out that abortion is illegal in Gaza (and, for that matter, homosexuality is a crime there). This is what happens when the ideology of intersectionality is so dominant that it determines whose suffering is valid and whose is not.

Worship of Hamas as an army of freedom fighters, along with the belief that any sort of violence is justifiable in an anti-colonial struggle, actually echoes the Israeli government’s contention that what it has done in Gaza is justified by its fight for survival. How can the average Israeli believe otherwise when they rarely see what we see nightly on TV, and when they have long seen bluntly anti-Semitic cartoons in the Arabic press. These drawings contain ancient tropes, including the belief that Jews engorge themselves with the blood of innocents. There are many examples of this vile mythology reworked to fit the current crisis. Here are two of them.

Let me add to this repulsive repertoire the Egyptian TV series inspired by The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which was broadcast in 2022 as a special for Ramadan. “Of course, what we read in the Protocols, it says it’s a kind of conspiracy,” notes the show’s protagonist. “They want to control; they want to dominate.” I don’t think Louis Farrakhan could have said it better.

***********

In the U.S., coverage of Gaza has been considerably more balanced than in Britain. But, here too, demography is a hidden factor in how networks and publications cover this story. If you get your news from over-the-air TV, you are likely to be of an advanced age—hence, the great number of medical ads. Older people tend to favor Israel, so the coverage is generally more favorable to the Jewish state. But as you go down the age ladder, opposition to Israel is greater, and a cable news channel like CNN, which wants to grow its share of the very desirable youth demographic, is more likely to be critical of Israel. The major influence of young people when it comes to news coverage is not their passion or their energy; it’s their purchasing power.

That brings me to the Times, which is caught in a demographic vise. On the one hand, its growth depends on amply covering the tastes of young people, especially women, which explains why the remake of Mean Girls merits six articles. But the Times must also maintain a connection to what it calls “legacy readers”—geezers like me—and we like print. That’s why a story like the recent, quite favorable essay on Jews in the Palestinian movement ran in the back of the Times Sunday magazine, while on the website it was front-page news. Still, given the difficult task of seeming credible to different groups of readers, and the equally arduous job of covering such a complex story, the Times has done remarkably well, offering a wide variety of perspectives as well as consistently showing its reportorial and analytical chops. I say that as a fierce critic of the Times’s many agendas. On this issue, they have been fair, and so has The New Yorker, but both rely on well-educated readers, the majority of whom are old enough to think that catfishing is a sport involving a rod and reel.

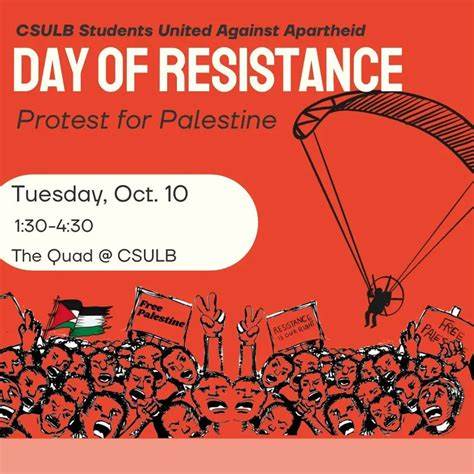

If there’s one aspect of the crisis that the mass media have failed to fully explore, it’s the origins of Students For Justice in Palestine, the group that played a major part in organizing the early protests. In order to examine that connection, I turned to the Times and The Forward, both of which ran well balanced investigations of this group, including speculation about the mysterious source of its funding and descriptions of the “tool kit” that S.J.P. sent to hundreds of campus chapters after October 7, calling for protests just three days after the massacre in Israel. Here is one chapter’s version of the poster featuring a paraglider like the ones Hamas used and a cheering crowd.

Basically, S.J.P. celebrated the slaughter on October 7. I can’t say how many of its chapters shared that view, but I can say that the first protesters who marched under my widow chanted “No Israel—Palestine.” In the early days of this movement, posters with photos of the hostages were defaced or ripped down. In Queens, students rioted at their high school, demanding that a teacher who had been photographed at a pro-Israel rally be fired. In Philadelphia, protesters gathered outside a felafel joint, chanting “You can’t hide, we charge you with genocide.” (My neighborhood Israeli takeout is now called a Mediterranean restaurant, and its Hebrew wall hanging is hidden behind soda cans.) Gestures like these targeted American Jews for collective punishment, sometimes because of their beliefs and sometimes just because of who they are. In the latter category, I’ll mention the Hasidic man who was beaten outside his building by an assailant who snarled, “Good Shabbos.” The Palestinian movement has evolved over time, so I don’t know how many protesters blame the victims of October 7 for their own deaths, but I would say that the implicit aim of the early demos was to silence and terrify Jews.

Still, pro-Palestinian demos have been disrupted as well, and violence against Muslims has been extreme to the point of shooting students and murdering a child. Palestinian points of view have been censored on many campuses, but, again, the context matters. Most universities have elaborate codes to prevent students in stigmatized groups from feeling threatened. But the sensitivities of Jewish students were not considered when these codes were devised, and professors at several universities have felt entitled to make statements or speeches at rallies that would horrify most Jews. (One professor told a crowd of students that he was “exhilarated” by the events of October 7.) In an environment where the racist equivalent of that sentiment is acceptable, the professor’s words might be considered free speech, but anyone who has taught at private universities, as I have, knows there are many things that can’t be said. To deny that Jewish students are entitled to the same consideration because they are white or “white adjacent” is to evade the inconvenient fact that Israel’s largest ethnic group is Jews of Arabic and North African descent. Another 20 percent are Muslim or Christian Arabs, and there are 200,000 Ethiopian Jews. Here is Ahmed Abu Latif, a Bedouin Sgt.-Mayor in the IDF. Israel is a brown-majority society stuffed into a white-supremacy paradigm.

***********

I know there are many Jews in the Palestinian movement, and I’m glad about that, because things would be even worse without them. Their agenda, as far as I can tell, involves the replacement of Israel with a multi-religious, secular, democratic state. To me, the idea that Jews and Muslims of the Middle East can live peacefully together in equality, while the heavily armed proxies of Iran tolerate such a society, is a utopian fantasy. But what seems naive today could, at some point, be visionary, and I’ll be very happy if my skepticism proves wrong.

I think Israel has the potential to be a just society, and I worry (usually at 5 a.m.) that its government is sealing the nation’s fate. But I’m even more concerned that social anti-Semitism will return among the young, and that the next generation of Jews will have to deny the particularities of their history in order to fit in. I’ve been there, done that. I was asked as a child to please show my horns; I’ve recoiled from a barroom hanging of an ugly creature called a Jewfish, and gaped at a painting of a wandering Jew with goat’s feet. I’ve seen things scrawled on walls and heard things screamed on the street since October 7 that hurl me back in time. How can I distinguish between my paranoia and my commitment to peace? I can’t. Right now, I’m torn between horror and angst, rage and guilt. It’s fucking complicated.