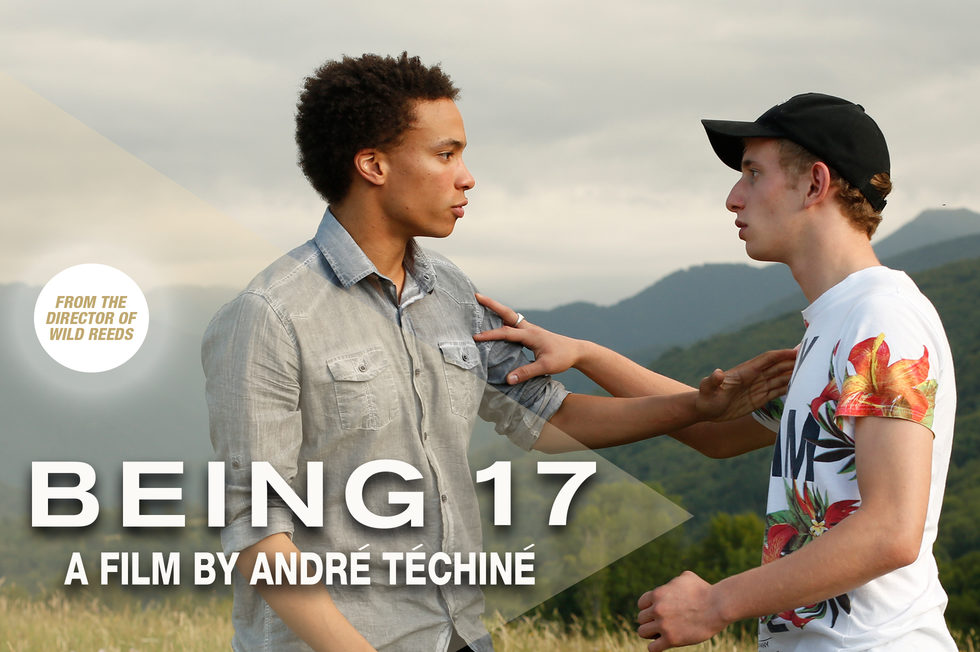

On my way to Andre Techine’s Being Seventeen, I stopped by Patisserie Claude for savory take-out and felt nicely sated as I found my seat in the theater, but the film stoked other appetites. (We cannot live by quiche alone, not even Claude’s.) Techine’s french lessons sky beyond “grub-first, then ethics” materialism. His scenarios feed your head and your heart, tuning every organ to desire’s pitch. I sensed Being Seventeen would be one of Techine’s full body-and-soul workouts early on when Thomas (Corentin Fila)—lovesome, bi-racial bully-boy (who’ll end up taking it like a man once he beats his fear of being gay) humps it up the mountain, past where his adoptive parents have their farm. The snow looks freshly fallen—perhaps it’s not that frigid?—and his secret brook hasn’t frozen over yet. He strips and dives in…

Being Seventeen burns like ice, like fire. I’m flashing now on what might be misread as a random segue (though this is a movie by a master so there’s no unmotivated benignity—every scene is a freebie that had-to-be). Damien (Kacey Mottet Klein), the movie’s other gay teen protagonist, walks past a Bastille Day (?) bonfire. He’s closer to being a flaming creature than the brown boy from the mountain, yet he’s more…seventeen than certain. (As the boys are beginning to come out to each other, he tells his běte noire: “I don’t know if I’m into guys or just you.”)

Being Seventeen’s coming of age story takes in class conflicts as well as race matters and gay desire. Damien lives with his mother Marianne, a doctor, while his father is a military officer on a tour of duty abroad. Thomas is a son of peasants who disdains bourgeois Damien for being “pretentious.” Though what really vexes Thomas is Damien’s crush on him, which scares him since he senses he shares Damien’s need. His fear gets amped up when the boys find themselves living together after Marianne invites Thomas to stay with her family. She’s treating Thomas’s pregnant mother (who has a history of miscarriages) and she realizes Thomas must come down from the mountain so he can visit the hospital regularly and avoid killer commutes to school, which have compromised his studies. The fractious boys don’t stop fighting—but hints of tenderness subsist despite elemental violence. Their angles on each other keep changing. They share dinners, joints and hits of high intellection. Mutual attraction develops over the film’s “trimesters” (which invoke the school year and Thomas’s mother’s pregnancy) until the haters/lovers absorb a lesson in loss that moves them to seize the night. Their consummation scene is for the Ages. But the morning after may be even sweeter. The boys dream on, thick lamb sausage pricks at ease. A tableau as happy as Renoir’s paintings of flushed fulfillment.

The eye travels in Being Seventeen—from perineums to the Pyrenees. Thomas’s mountain roots allow Techine to find environs for facts of feeling in primal rock formations and heavenly vistas. The mountain gives Being Seventeen its breathtaking finale—hot to embrace the lover he’d head-butted a season before, Thomas races headlong down a slope as Afropop music soundtracks his sprint.

Armond White has commended Being Seventeen’s “lithe” camerawork, noting cinematographer Julien Hirsh is “especially good at catching fleeting emotions…the boys’ fast glimpses of ardor and hesitance. Their complex first love is apparent even beneath their angry surface—the most natural-seeming acting in any movie this year.”

I’m locked on one moment when Thomas’s open face registers his fear-into-trembling joy as he holds his infant sister for the first time. (He’d worried his parents might prefer their new “real” daughter but all that’s gone in a rush.) His acting took me back to a sequence in a classic work of direct cinema, Seventeen, when an African American teenage father in a Muncie, Indiana maternity ward sees his new-born infant for the first time. (Disclosure alert: that documentary was made by my sister Joel DeMott and Jeff Kreines.) I wouldn’t be shocked if Seventeen’s tight focus on teens navigating race, class and illicit desire was in the brainpan of Being Seventeen’s brain trust (who chose to use hand-held cameras like DeMott and Kreines). Per Techine: “I wanted to get as close as I could to the physical bodies of these two adolescent young men, and also to get as close as possible to the body of the mother.” If Techine hasn’t seen Seventeen, I’d bet his co-scriptwriter Celine Sciamma has.

Sciamma is best known for her movie Girlhood which Africanized the jeune fille prototype. Haven’t seen her film but this sequence of teen Afropeans dancing to Rhianna, which has turned up on YouTube, justifies its existence.

Techine loves to go pop himself. In Being Seventeen he uses music (as ever) “to show very specific things”: “we hear the African music at a moment of complete exaltation for Tom. I didn’t specifically choose it to make a point about his African origins. This I felt was a music that reflected his own personal journey —…and this moment in which he finds himself at the end.”

Thomas’s journey seems like an echt French trip since La France Profonde is all up there on the screen in Being Seventeen (along with the ugly prospect of mechanized farming and scheduled sex acts via gallic Grindr). There’s love, death, birth, peasants, cows, wine, café au lait, bookishness, national f’ing health, war against Islamist terror, the officer corps…

Being Seventeen is suffused with Techine’s love for his country. He films a military funeral reverently, integrating it into the flow of feeling that impels the boys to act (finally) on their gay imperatives. Techine honors French officers and queers. His range of affirmations calls to mind Orwell’s case for patriotism during the blitz. Orwell equated “England your England” with a bent, extended family (not that he was beamish about “relatives” in higher reaches of UK’s class structure). He proposed one’s country was like an “everlasting animal stretching into the future and the past, and like all living things, having the power to change out of recognition and yet remain the same.” An apothegm worthy of Techine’s full frontal vision of deep France.

Being Seventeen complements American art that gets our beast of a nation. Bless those auteurs who aim to stretch themselves on this score. Spielberg’s Lincoln and Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton find the present in the country’s past. But it’s harder to cut to the core in real time. And (pace Ben Kessler) it’s more necessary now than ever since the country may be trumping itself.

Serious novelists are a national resource here as they’re required to be alive to what’s new under the sun. I’m reminded how Atticus Lish’s close imagining of new (Asian and Latin) immigrants in fellahin Queens, Preparations for the Next Life (2015), taught American readers how this country could change out of recognition yet remain the same.

But there are American novelists who may not be up to the gig. Richard Ford’s recent Times review of Bruce Springsteen’s memoir made me doubt his democratic instincts. Ford writes: “The perpetual fascination of Bruce (I never, give you my word, shouted that out at a performance) is simple: how the hell do you get from Freehold, N.J. to this”[i.e. fame, fortune, artistic cred and command performances for the likes of Richard Ford, “my wife, Governor Christie, Steve Earle and 19,000 strangers”]. Ford means to lay emphasis on Springsteen’s vaulting ambition and craft but in the meantime, he comes on like an ugly New Yorker, backhanding all the Freeholders in flyover country. To be fair, Ford may have had originary rock ‘n’ roll towns like New Orleans or Memphis somewhere in his mind and he takes back his snot, allowing it’s impossible to map anyone’s identity. But no American novelist should cop to being so blankly unresponsive to mysteries of Freehold: “’a one dog berg’ down in that lost part of the Garden state that you never thought about until you hear the words Bruce and Springsteen in that order.” I wonder what places Ford deems worthy of his cerebration. His shtick fits the template of Times-style urbanity. And that’s what it signified to me earlier this month. Now that I’ve seen Being Seventeen, though, Ford’s attitude toward “lost parts” of America bring home the virtues of Techine’s true feeling for France’s back country and outliers. We should all be so provincial.