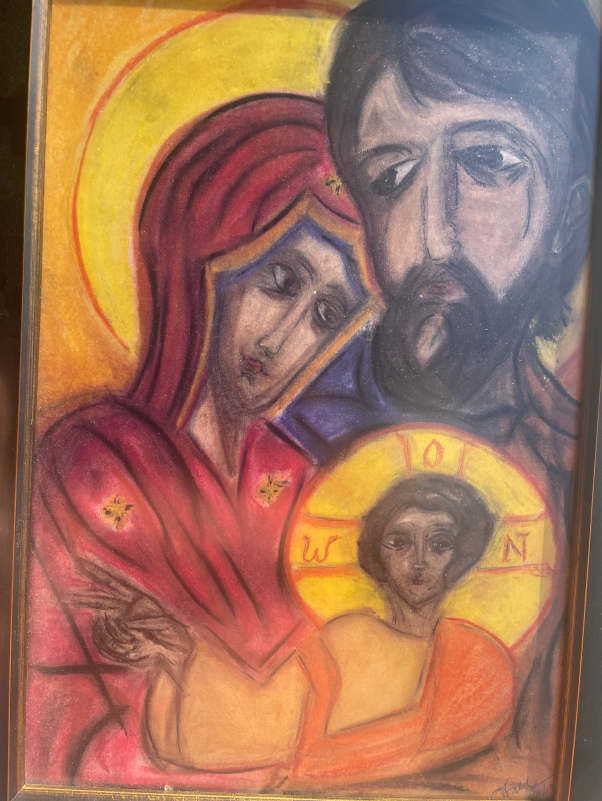

While quietly crossing the threshold from a most difficult year into a (hopefully) better year, I lit a simple fire in an old tire rim, and with Orion twinkling in the darkness above, I contemplated the religious icon that accompanies these words.

Mary and Joseph are exhausted, thick shadows haunt their soulful eyes which are apprehensive with sadness and worry. They lean into one other, as if each would fall over without the other.

The child Jesus is placed in between them, like the ballast keeping them upright. His face reveals that he is absorbing the trouble in the hearts of his mother and father.

Yet a golden light surrounds his countenance, as he looks directly at you, at me.

The Greek letters in the golden glow reveal his name: “I AM” (Exodus 3:14).

Big credentials for a small, troubled boy.

He is speaking to us with the gesture of his right hand, a “hand speak” as precise in icons, as it is in signing with the deaf.

This is an exhausted refugee family, having gone overnight from being visited by Kings, to running for their lives. We know too well the bloody reasons for their exile.

Two thousand years have past, and still today thus is life for far too many families.

Whole families, throughout the world. Their faces blend into the same sorrowful, but blessed, togetherness of this icon:

Families of Haitians in the jungles of the Darien gap, families of Syrians in Turkey,

of Afghans in Pakistan, of Sudanese in Congo, families who perish altogether in the Mediterranean Sea.

These anguished families number 82 million people today, as we live and breathe and begin a new year.

Most of these refugees are women and children, fleeing violence and death in their homelands.

Pope Francis referred to their plight in his Christmas message, as a massive and forgotten human tragedy.

“These nightmares never seem to end, and by now we hardly even notice them. We have become so used to them, that immense tragedies are being passed over in silence.” (Urbi et Orbi, Christmas 2021)

There are also other kinds of refugees: their lives are marked by “The flight into virtual.”

The flight of many people from their own humanity, from deep human bonds, has become for us a plague. Alarms are sounding about the mental health of children and young adults, of lives spent virtually streaming or gaming.

Much concern is now paid to the tragic “devolution” of the human being.

People are losing the art of how to befriend and mature in friendship, how to define yourself with healthy boundaries and respect the boundaries of others, how to both compete with rivals and challenge opponents in a healthy way.

We see the consequences.

Often, the flight into virtual is the flight into emptiness, and then the flight into big trouble, as you try to deal with the emptiness.

Pornography, gambling, dark chat groups, movements against values and principles that make us able to live in a civil and civilized way, sites that enable, rather than challenge, tendencies to baseness, racism, and falsehood.

If the emptiness gets to you, and you are thinking of suicide, the dark side of the web will encourage you to just “go ahead,” and even offer suggestions to help you end your life.

When it comes to truth, and its liberating discovery and unfolding, we live rather in a time of gaslighting, of smoke and mirrors, of fierceness in encounters, of intense division and hatred.

The tragic flight is from humanity itself.

Yet, as we flee from our very humanity, we celebrate at Christmastide the awesome wonder that God entered into it gladly, in order to awaken within us all the best angels of our human nature.

This is a hopeful cause for joy, especially as we begin a new year of intense challenges.

Humanity in Haiti is also at a very low ebb, as many of you know from the news.

A lot of our time now is spent trying helping relocate internal refugees from city-wide violence (especially in Martissant), trying to help kidnapped people get freed unharmed (at present, two Catholic seminarians), trying to help the homeless rebuild their lives (the earthquake in the south was only five months ago), trying to help bind the wounds of victims of armed bandits (a Catholic priest was shot yesterday in Miragoane), trying to grieve and help bury those who did not survive armed assaults (on Saturday, we will bury Marco, who grew up in our NPH homes and worked as a “blood runner,” getting blood from the Red Cross for our hospitalized patients). And, of course, trying to keep our normal work going.

The Pope is right. We are too used to the atrocities. The overriding reaction is silence.

Bishop Dumas wrote a strong condemnation, lament, and call to action on the shooting of Fr. Francois, as has been done many times by Bishops of Haiti. The usual response is the sound of crickets.

As the saying goes, “it is what it is.”

But people of good will, and people of faith, cannot let it go.

“It is what we are allowing it to be.”

And we need to work hard to change it. Along with many of you, we will fight with all our ability to change what should not be, what should never, ever have become “what it is.”

This year in Haiti, people on the street don’t say: “have a good year” (Bon ané); instead they say: “have a good battle” (Bon kombat).

Everyone here knows what they are up against.

This phrase “Bon kombat” echos the words of St Paul: “I have fought the good fight, I have run the good race,” (2 Timothy 4:7)

The good fight will not leave you looking (or walking) like you did in your prime.

The good race will guarantee your intimate knowledge of the loneliness of the long-distance runner.

But St Paul finishes by saying, “I have kept the faith.”

This is a great New Year’s resolution, wish and prayer:

May we keep the faith…

in our humanity,

in ourselves,

in each other,

in what we can create together,

and in God.

Blessings of peace, strength, courage and wisdom for you and your families, in a new year of challenges. Thank you for your generous and precious help over many years,

Fr Richard Frechette CP DO

Port au Prince Haiti

January 6, 2022