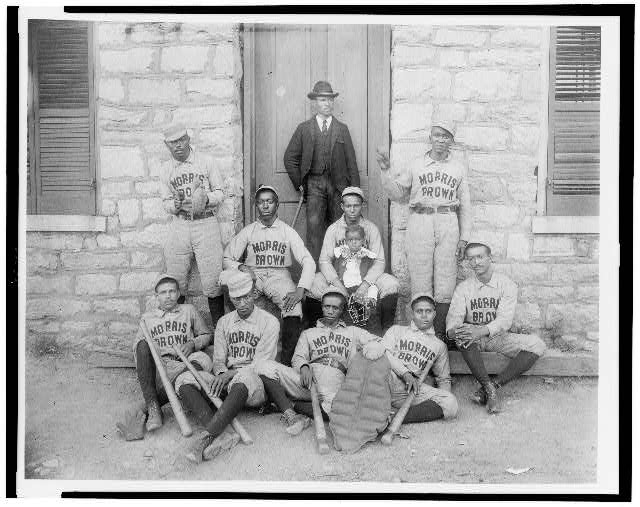

At the world’s fair of the 1900 Paris Exposition, W.E.B. Du Bois, Daniel Murray, and Thomas J. Calloway organized the Exhibit of American Negroes to represent the history, culture, and institutions of their people. (The Paris world fair was a celebration of ruling ideas of progress intended to uphold “achievements of the past century and propel development into the future.”) The Library of Congress online archive has collected the photographs, charts and other materials curated by Du Bois et al. Looking through the files, among the images of black laborers, students, mothers, organizers, homes and churches, a picture of Morris Brown College’s black baseball team resonated with a young African American man, a century on.[1] Du Bois, or perhaps Calloway, must’ve seen how this tableau of a true team evoked more than stats or won/lost records ever could…

Your editor sent Peter Wood this photo after reading how Jackie Robinson’s example helped propel Wood on his path to writing books like Black Majority and Near Andersonville. The photo also went to First contributor C. Liegh McInnis since he’s a baseball fan with deep feelings for the Negro Leagues as well as a certain distance on Jackie Robinson and the ideal of integration.

Wood responded:

As someone who actually saw Satchel Paige pitch in the Big Leagues, I loved the Morris Brown photo…Those players look like major league material to me.

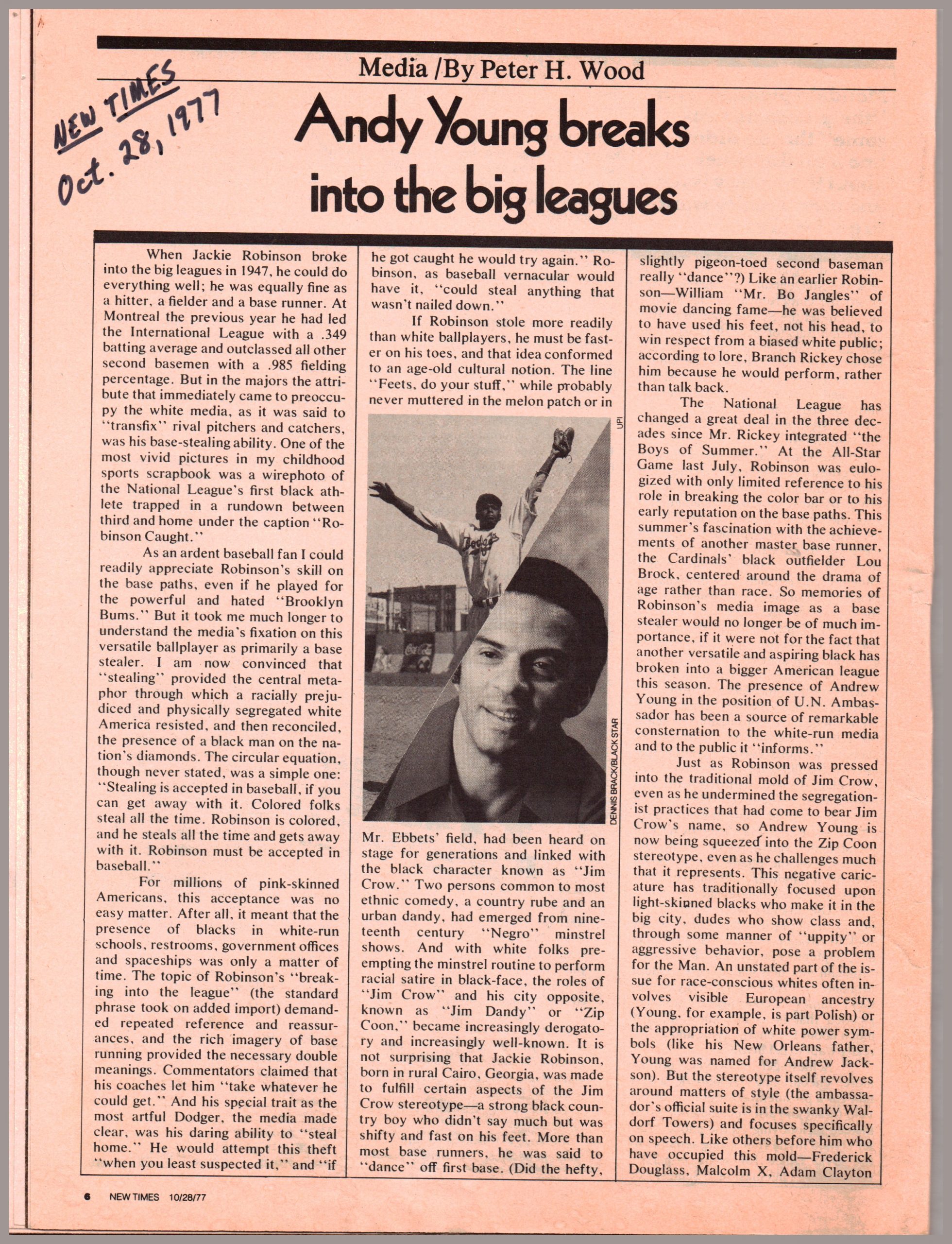

I attach a short piece I wrote during the Carter administration in which Robinson figures. (White papers obsessed about his “stealing”!) [Scroll down to read Wood’s piece.]

The photo (and Wood’s back pages, which I forwarded on to McInnes) prompted the following comment from McInnes:

Thanks for sharing the Morris Brown baseball pic. It reminds us of the amazing human spirit that even during the worst of times people can make life livable and even beautiful. For those students, playing baseball was about being as human as possible while using that activity and others to reclaim their humanity. It reminded me of the 1920 JSU football team (here) that was the undefeated Mississippi-Louisiana champs. One of the members of that undefeated team, Percy Green, graduated and started the Jackson Advocate in 1938, one of the oldest black newspapers still publishing today and the periodical that published me a great deal when I was a beginning writer.

I couldn’t help but chuckle at Mr. Wood’s story of being a child and wondering why so many people were in the home Cardinal stands rooting for the hated Dodgers. Interestingly enough, Mr. Wood was not alone in his childhood bewilderment. Professor Jim Brown, a white professor of history at Tougaloo College, once told me a similar story about asking his father why so many people were in the home Philadelphia Athletics stands rooting for the Dodgers. Of course, it was black Philadelphians rooting for Robinson. In an ironic twist, my grandfather, a man who participated in Negro League Barnstorming in Mississippi, never stopped rooting for the Yankees, but, from what I’m told, my grandmother would make him “be quiet” when the Dodgers were on.

In his article, Mr. Wood leaves no stone unturned and no metaphor unexamined, covering all the bases to show how language is often the primary battlefield of change, especially as it relates to race. In short, the article is a wonderful linguistic, syntactic, and semantical engagement of the power of words and an affirmation that the power of life and death do lie in the tongue. Wood also affirms why my pops watched the game with the sound muted because he didn’t want to hear white men pontificate about black talent that would be called “athletic” in contrast to the “heady” white players and because “if you need someone to tell you what’s happening, then you are probably not smart enough to be watching the game.” While I thought that my pops’ position was a bit odd for a man who could talk all day about listening to the radio for the play-by-play of Bob Gibson on the mound, I eventually realized that television allowed him to do what radio never did—enjoy the game while usurping white narratives. Thus, my pops’ ultimate goal fits nicely with Wood’s ability to place Robinson’s greatness in terms of a wider socio-political movement with Andrew Young presented as another installment of the “new Negro,” mostly new because he, like Robinson and others before him, simultaneously defied certain stereotypes while embracing and/or refashioning their own tropes of blackness. As such, Wood rightfully infers that a major problem that whites had/have with Robinson, Young, and others is that they were self-conscious and self-loving enough to craft themselves for themselves without asking for permission from the white power structure while still demanding a seat at the American table of power. Sadly, reading this article now, it is clear that “the league in which Young play[ed]” was never fully integrated as the white establishment and public never solved its formula of racial anxiety. It leaves a Black Nationalist like me to wonder how much better the world and, particularly, black communities would have been if more efforts had been invested in creating sovereign black institutions. Of course, some may read this and say I’m discounting the work of Robinson, Young, and others. Yet, my point is not to discount their work but to make clear that their it fell on many deaf ears, hearts, and minds, and now the black community continues to wander without a map in the wilderness with no boots or bootstraps, constantly going with our hat in our hands, begging and depending on the charity of the white power structure rather than on our self-determined diligence. Wood’s article is more evidence that America’s attempt at “integration” didn’t fail due to deficits in black intelligence and morality but because a good number of whites were never willing to share power. Hence I offer an urgent commentary— “Another Trojan Horse: Newly Proposed MS Senate Bill to Close 3 Mississippi Universities”—that underscores how neo-Confederates are still waging a Civil War where Mississippi remains ground zero with a domino effect for the rest of the country. Take care.

Here is Wood’s piece, relating Robinson’s persona to mainline white views of Andrew Young’s arrival on the national and international scene in the 70s…

1 Editor’s note: that “young African-American man, a century on” is my son who went on to muse about how the photo reminded him…

of my best times in sport—tired legs, after a good game, leaning back with my guys. Like any team this Morris Brown squad has players that don’t make it on the field—a suited coach(?) and a little kid, a son or daughter of one of the players(?). No disrespect to high critiques of exhibits at the Paris exhibition by academic theorists, but perhaps we should ease into the every dailiness of Du Bois’s/Callaway’s artful archive.

See more at: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3c14266/?co=anedub.