Li Wenliang

Li Wenliang

“In this world there are no heroes descended from heaven, there are only ordinary people who come forward.”

During the lockdown in China prompted by Coronavirus, folk musical and ritual activities have been on hold—but some brave local performers have been reflecting the outbreak in online songs criticizing the Party’s handling of the crisis.[1]

First, some background on the folk traditions from which these songs emerge. Despite far-reaching political campaigns after the Communist revolution of 1949, traditional life-cycle and calendrical rituals managed to cling on; and following the end of the Cultural Revolution, the collapse of the commune system from the late 1970s led to a huge revival of traditional observances. At the same time, they now faced a new challenge in (Chinese) pop culture; and with the vast countryside remaining alarmingly poor for many years, rural dwellers began a vast migration to the cities. Still, the ritual market is served by a variety of rural performers such as folk-singers, opera troupes, shawm bands, and folk ritual specialists.

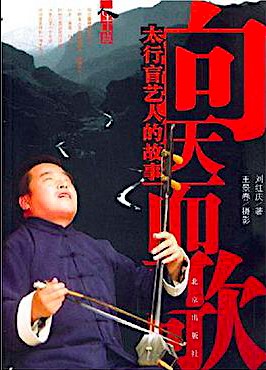

Among these performers are blind bards, singing auspicious songs for rituals. In the Taihang mountains of Shanxi province, the blindmens’ propaganda troupe of Zuoquan county are the subject of one of the most illuminating and harrowing books on rural life in north China by Liu Hongqing, who writes with great empathy about the lives of poor peasants—not least the wretched fate of women in an area that remained chronically poor under Maoism.

Such stories, all too common in rural China, make an important corrective to rosy state propaganda, putting into perspective scholarly accounts of machinations within the central leadership; and the fierce, anguished singing and playing of groups like this are utterly remote from the bland, cheery ditties of official troupes.

Liu Hongqing’s book.

Liu Hongqing’s book.

The Zuoquan troupe chronicled by Liu Hongqing has always adapted to the changing times, from the warfare of the 1940s through Maoism to the reform era since the collapse of the commune system in the late 1970s. In the latter period they began to perform stories criticizing corruption.

Itinerant performers like blind bards are occasionally enlisted to explain state policies among the folk, but they may also express resistance. In a post on bards of Shaanbei I explored the themes of AIDS, SARS, and novelist Mo Yan’s portrayal of a bard protesting at unjust local government requisitions.

Mourning Li Wenliang

And now the Coronavirus outbreak has given new life to the debate over freedom of speech. The Party has recruited performers to play an orthodox role in promoting public health, but independently-minded folk performers have also taken a critical approach.

The Wuhan ophthalmologist Li Wenliang was among the first whistleblowers. Before his death on 6th February at the age of 34 he was punished for “spreading false rumours”. Though the central Party later backtracked on criticizing him, the widespread tributes on Chinese social media mourning his death—at a time when popular resistance to state power (notably in Xinjiang and Hong Kong) is otherwise muted—were largely an outpouring of resentment against the state’s irredeemably secretive policies in reaction to the outbreak. But online discussions continue to be censored.

A tribute to Li Wenliang, posted on WeChat on 8th February and only deleted by the 13th, featured a folk-song movingly performed by none other than Zuoquan blindman Liu Hongquan. Do listen to the song, since you can no longer hear it on WeChat:

://limanshanblog.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/whistleblower.mp3

The lyrics were written by Peking University economist Zhang Weiying, a native of Shaanbei who in 2019 composed, and sang, a folk-song in defence of dissident law professor Xu Zhangrun.[2]

The Northwest Wind

I also find some great new satirical songs about Coronavirus by the enterprising folk-singer Zhang Gasong (b.1989) His own song about Li Wenliang appeared only very briefly on Weibo. Another one, criticising a range of responses to the crisis, with incisive visuals, was also soon deleted from Chinese social media:

And he created this song to cheer up his granny by satirising his unexpectedly lengthy sojourn upon returning home for New Year—a common predicament:

Musically the gutsy “northwest wind” folk-song style makes an incisive medium, with funky sanxian lute.

Brought up in a poor village of Baiyin municipality beset by frequent drought, Zhang Gasong relished the song festivals at temple fairs; he managed to attend college, but found himself drawn back to his local culture, becoming a collector as he studied with noted folk performers—many of them blind.

A busy touring schedule has brought him celebrity. As his horizons have expanded, he’s absorbed new pop styles; yet he’s aware of the dangers of losing himself in the urban jungle, and as he astutely comments, he doesn’t like to be forced into representing a contrast between rural and urban China.

Zhang Gasong’s work in collecting the local song cultures of Gansu, with its complex ethnic tapestry, is part of a long tradition dating back to the Maoist era.

By contrast to such bold views, the recent wave of balcony singing in Italy seems remarkably conformist. One awaits more critical musical expressions in the USA…

NOTES

1 This is an edited version of recent posts about Coronavirus on my blog, which contain more on the folk musical background: click here and here.

2 See this article in a lengthy series by Geremie Barmé; for his translation of Xu’s essay on the virus, see here, and here. Also by Barmé is a recent NYT article.