William Kornblum’s Marseille: Port to Port is (per Howard Becker) “a new kind of travel book.” What follows are (slightly adapted) excerpts from Kornblum’s testament to sociological imagination and soulful uses of ethnographic method…

ALONE IN THE MARSEILLE OBSERVATORY

“It was the port that seamen talked about — the marvelous, dangerous, attractive, big, wide-open port of Marseilles. And he wanted only to get there.”

— Claude McKay, Banjo (1929)

The heart of downtown Marseille is its Old Port. The quays that border its rectangular expanse of water on three sides are edged by a forest of masts and towering yachts. The fourth side is open to the sea through a narrow passage between two rocky cliffs at the port’s entrance, an opening in the cliffs called a calanque, a signature geologic feature of the region’s spectacular coastline.

On the northern side of its old port are two blocks of identical, four-story, mid-twentieth-century apartment buildings. Their unadorned balconies overlook the inner harbor and offer a clear view of distant Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde, golden and vigilant above the port. The windows behind the balconies glow in the setting sun. These long and somewhat heavy looking apartment blocks are separated by the glorious eighteenth-century Hotel-de-Ville, spared destruction during the German occupation of World War II. It is now the city’s political power center, from where the mayor rules: The modern apartment buildings that flank the City Hall were once the site of notorious tenement slums. Walk-ups that dated to earlier centuries leaned precariously over the narrow streets. The area hosted a thriving red-light district and every type of dive bar. This was the neighborhood known to Harlem’s Claude McKay as the Ditch (La Fosse). He also called it Boody Lane. When he landed there in the 1920s, Banjo, his alter ego,

instinctively… drifted to the Ditch, and as naturally he found a girl there. She found a room for both of them. Banjo’s soul thrilled to the place — the whole life of it that milled around the ponderous, somber building of the Mairie, standing on the Quai du Port, where fish and vegetables and girls and youthful touts, cats, mongrels, and a thousand second-hand things were all mingled together in a churning agglomeration of stench and sliminess.

His wonderful Marseilles! Even more wonderful to him than he had been told.

McKay had landed in Marseille after a few months working on a tramp steamer. Merchant seamen “on the beach,” waiting for their next ship, shared money and wine in an international brotherhood of black and brown souls, outcast itinerant workers drifting through the world’s ports.

When Walter Benjamin visited Marseille in the 1920s, he knew the area as Les Bricks, “the red light district…A vast agglomeration of steps, arches, turrets, and cellars…this depot of worn-out alleyways is the prostitutes quarter. Invisible lines divide up the area into sharp, angular territories like African colonies.”

But contrary to its reputation as a popular haven for whores and criminals, the district also provided housing for dockers and their families, most of whom were French Marseillais. Nonetheless, Himmler called it “the wart of Europe,” and in 1943 at the height of the occupation, the Nazis and their Vichy French collaborators used the opportunity of counter resistance actions and the claim that the old neighborhoods were housing terrorists to reduce the entire area, with the exception of the historic City Hall, to rubble. Two thousand Jews who had lived there and in the vicinity were sent to the extermination camps.

The postwar buildings and their balconies on either side of the City Hall create a long arcade of vaulted storefronts. These are the residential apartment blocks designed by Fernand Pouillon to replace the buildings that had been blown up by the Nazis in 1943, Some of these apartments remain occupied by families who had been displaced during the war. Most of the commercial ground-floor space contains busy bars and restaurants offering Provencal seafood, attracting a thriving tourist trade. Here and there among them are some local favorites, like Chez Madie Les Galinettes.

My wife, Edith Goldenhar, and I discovered Chez Madie on a formative visit to Marseille in 2012. I had been in Marseille a number of times for work, but this visit was for pleasure. For the first time I felt the city’s Mediterranean allure…

The Guide du Routard recommended Chez Madie Les Galinettes as one of the more authentic Provencal kitchens. Indeed it was friendly and authentic, “sympa,” as the French would say. From the terrace of Chez Madie, at an umbrella-shaded table, our gaze was drawn up the steep hill on the south side of the Old Port. On her perch atop a two-hundred-foot bell tower, a Golden Madonna. and child were shooting bolts of reflected sunshine. The Byzantine-style Basilica Notre-Dame de la Garde, known to all as “La Bonne Mere,” rises from the ramparts of the fort, built in the mid-15oos on the order of Francois Premier, known as the Chateau Builder. Much earlier, in the eleventh century, a local priest constructed the first chapel on top of the hill known as La Garde, the lookout place. While it is easy to get a surfeit of major cathedrals in European capitals, Notre-Dame-de-La-Garde is a Marseille original.

From the ramparts encircling the basilica the views of the city and of the sea beyond are extraordinary. Inside, the basilica glows; green stone and mosaics are illuminated by color streaming through stained glass. And it’s the mariners’ church, above all. Marseille’s special identity among French cities came to me through unexpected popular expressions of gratitude and faith. These are inscriptions on the walls and ex votos from the survivors of shipwrecks and other catastrophes. One ex voto reminded me of early boating experiences with my young family in New York Harbor that I’d rather forget.

A family’s small fishing boat, a typical barquetta of the northern Med, is in peril. A fierce and sudden wind, perhaps the Mistral, turns the picnic outing a la marine into a matter of life and death. Mom is rowing through angry whitecaps. Dad stands waving a distress signal. No life preservers. It’s comforting to know that, with the grace of God, this near disaster ended in rescue.

The ex votos were of a piece with the creative graffiti in the Panier and the crooked hillside neighborhoods of the city we traversed on our way up to the basilica and down the other side to the corniche that runs along the sea on the city’s south side. The twin dramas of nature and humanity played out on Marseille’s craggy shoreline and nurtured its special quality of folksiness tinged with melancholy. These aspects of its identity transcend class divisions. The proud soulfulness of its people is expressed in the city’s art and literature. It is also reflected in the tenacity of neighborhoods carved into limestone cliffs and coastal calanques. As a student of cities and coastal communities, I knew during that visit in 2012 that I would return for more exploration.

Two years later, in 2014, I returned alone to Marseille. I would live there for six months. My wife would visit me for a week here and there, when she could leave her own work in New York. I was about to turn seventy-five, taking a last university sabbatical after over fifty years of teaching. The first two or three days of jet lag and unaccustomed solitude were difficult. To boost my spirits, I headed for the Old Port and the familiar terrace of Chez Madie…

Tourists and locals wandered past while I lingered over coffee in the mid-September Marseille sunshine. The time I would have to explore the city seemed to stretch out endlessly ahead of me. I welcomed the challenge of learning to feel at home in Marseille. But I also felt a little lost, a stranger in a city that made a student of cities feel like how a foreigner must feel just starting to settle in New York City. Here in Marseille, Arabic is the second language, just as Spanish is in New York City, or at least in my neighborhood of Jackson Heights, Queens. I speak no Arabic, and the Marseille French accent is demanding. Eventually I would get better at it, as I spent time with friends in the northern neighborhoods of the city, but at first it was frustrating not to catch the meaning of casual speech that would have been clear to me in Paris.

I began walking up the Canebiere toward my apartment, passing the gleaming Bourse, the Chamber of Commerce, and the immediate commercial center in the blocks just above the Old Port. I stopped in front of the OM store, to admire the jerseys and team photos. L’Olympique de Marseille, with its stadium in a posh south side district, is to the city what the Brooklyn Dodgers had been to me and my baseball-obsessed father. Marseille’s pride and sense of solidarity owes a huge debt to its home team. Football, with an emphasis on the foot and not the helmeted head, holds the city’s youthful population in crazed fandom. Everywhere one looks in Marseille there are children and teenagers kicking a soccer ball around. An ex-athlete can always find a bench near some players whose youth and grace demonstrate why throughout the world it’s known as the “beautiful game.”

Once considered the Champs-Elysees of Marseille, the Canebiere is a broad, tree-lined boulevard that bisects two largely Arab neighborhoods, Belsunce on the left and Noailles on the right, and ends at the cathedral of Saint-Vincent de Paul, known also as Eglise des Reformes. Yanks on leave in Marseille just after the war called it the “Can-a-beer,” something of an irony, since the actual name derives from the Latin word for cannabis. In the second half of the seventeenth century, when the boulevard was part of Louis IV’s vision for the city, the area beyond was still lined with hemp fields used primarily for making maritime rope and hawsers. Today the avenue retains a shabby grandeur as hopes to gentrify and attract upscale investment focus on the restoration and reopening of a luxury hotel at the foot of Noailles.

During my academic residence in Marseille I was generously housed in the Cinq-Avenues neighborhood of the city, above the top of the Canebiere, in the empire-style Pare Longchamp, home to the Museum of Fine Art. My one-bedroom apartment was at the top of the Maison des Astronomes (Astronomers’ House), on the grounds of an old observatory. Its four huge windows overlooked the city toward the west. Sunsets were symphonic.

In my perch above the city, I was at first alone much of the time, missing my wife and family back in New York. I was feeling a bit homesick, but in Marseille that melancholy would not last for long. I was meeting with people who were eager to show me their Marseille and was making an effort to meet people who came from different sections of the city and from diverse social worlds. I was also learning about figures from the city’s past. Their Marseille stories will appear in the chapters to come. My phone rang that afternoon just as I entered my flat. An anthropologist friend, Kenneth Brown, a professor of Middle Eastern studies, resident of Noailles, a man who knows how to stay fit and enjoy life, wanted me to meet him for a swim at the Plage des Catalans. There would be a stunning sunset at the beach, he promised. The water would be ideal.

Inside the apartment, my couch beckoned. But gravity’s napward tug gave way to the “Marseille Effect”: a burst of energy for adventure. I grabbed a bathing suit and towel, crossed the back side of the park, and hopped on the #81 bus. In about twenty minutes the bus took me back to the Old Port and up the corniche, past the Pharo, to the welcoming patch of sandy beach at “Les Catalans.” Beyond the children playing at the water’s edge and some couples bobbing together not far from shore, I saw my friend Ken swimming easily across that beach about fifty yards out. I swam to meet him. The clear azure water was refreshing but not cold. As promised, a red ball of fire was settling into the western horizon. Shadows fell on a velvet sea.

JEAN SYLVA: LA VISITATION

I first spotted Jean Sylva on a dusty football pitch. Lean and long, impossibly light on his feet, he seemed to float above the crowd of teenagers who darted around his legs. When we were later introduced, he gave me a wide, welcoming smile. I wasn’t surprised to learn Jean was the chief organizer of many of the better things that went on in the neighborhood, including the Local, a storefront that served as an informal youth and cultural center. This was a social hub Lt La Visitation, the housing project of four-story walk-ups on the avenue des Aygalades, above the Parc Francois Billoux and cross from the Saint-Louis sugar refinery.

Almost a quarter of Marseille’s entire population, over two hundred thousand people, live in apartment complexes like La Visitation that crenellate the ridges above the city’s north side. Bisected everywhere by highways and railroad tracks, Mareille’s northern housing blocks seem almost to tumble through narrow valleys into the deindustrialized commercial port, which extends for miles along the city’s northern seacoast to the large shoreline neighborhood of L’Estaque.

La Visitation is a midsize housing estate, with about six hundred residents living in four-story walk-up apartments, Built on what was originally Catholic Church property, it is far less densely populated than La Castellane and other more massive apartment blocks, but it is also one of the more isolated estates as it is surrounded by factory sites, many abandoned. The #31 bus from the Bougainville subway station stops directly at the entrance road. Running every fifteen or twenty minutes, it is a lifeline of the cite. A stately corridor of London plane trees at the entrance offers a sun-dappled welcome to a new visitor.

The Local was an informal social center in La Visitation’s small central courtyard. It included two ground-floor rooms in the same building that housed the convenience store, the single commercial outpost in the complex. The nearest other stores were a twenty-minute walk away. During my extended stay in Marseille (2o14-2o15), Jean welcomed me and helped me feel at home in the neighborhood. I began to make regular visits to the Local to see Jean and his young neighbors at La Visitation. Much of what I have learned about life in Marseille’s housing projects comes from hanging out there and going with Jean and others from the neighborhood into other housing estates on the north side. I have visited some of the larger housing estates, like La Viste, La Busserine, and La Castellane, which have far more developed, professionally staffed community centers that sponsor programs for young and old. But smaller and more isolated estates, of which there are many, tend to be less well endowed with social resources. In Marseille and throughout France, the public housing estates are managed by local leaseholders in the nonprofit and for-profit sectors, according to rules established at the national level. However, just as the leaseholders vary from one cite to another, so does the quality of management, the level of resources, and the depth of commitment to social programs.

The scene Jean and the active neighbors created at the Local, with modest support from the regional government and Logirem, the cite’s socially aware leaseholder and property manager, had quickly become a safe indoor haven for the neighborhood’s children and some of its teenagers. It was indeed a welcoming place, although somewhat ad hoc and institutionally tentative, similar to so many neighborhood initiatives in the lower ranks of the urban world. The Local had been furnished with donations — a TV console, some battered couches, and a table and chairs. The drab walls were enlivened by powerful hip hop-influenced art painted by CROS2, a local artist and designer otherwise known as Vincent Landry.

During the time I lived in Marseille at the Maison des Astronomes, I tried to come to the Local every Saturday. Sometimes I made sandwiches for the kids and always contributed some snacks to add to what others had brought. On a typical brisk late autumn Saturday morning, I found the Local filled with children. Ten or twelve boys and girls ranging from eight to twelve years of age were writing thoughtful responses in spiral notebooks regarding a question Jean had put to them before I entered. At the center of the group were two adorable African boys, identical twin brothers of about eight or nine. Today they are star students at the nearby College Rosa Parks, or perhaps as you read this they are entering the university, but when I first met them at the Local, they were attending the primary school at La Visitation. Shy, studious boys who loved to read and write, they appeared for these Saturday workshops as soon as the doors opened.

Four girls whose beaming faces shaded from mahogany to pink, each a grade or two younger than the African boys, were also writing in their notebooks at the central table. On a couch, three Roma boys from households recently settled at La Visitation were fiddling with CDs and a boom box, thus avoiding the writing workshop. In another corner of the room, three preadolescent girls were reciting and memorizing the words to a popular rap number about a boyfriend who comes to see the singer, on a motorcycle: “avec une grosse moto, une moto…” On the edges of the room, a few adult neighbors, relatives of the children, sipped coffee and chatted…

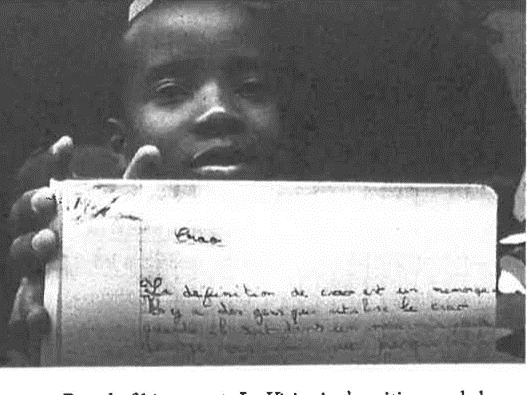

As it turned out, this was still the France of Descartes: the kids were absorbed in writing on a philosophical question. Before my arrival that day, Jean had led them in a discussion of the slang term crao, and they talked about some examples. He asked them to write some thoughts about the subject as they experienced it. I had never heard the term. Laughing, Jean explained that it was pronounced cra au, two syllables, stretched out. It was local slang for all sorts of intentional and unintentional fabrications, fibs, white lies, bigger lies. It could apply to systems of fabrication and the artful distribution of untruth and exaggeration, including merchandising, advertising, and, of course, politics. At La Visitation, the expression “C’est du crao” could characterize discussions about trivia or momentous events. The ubiquity of crao made for compelling and lively discussion. It struck me as a somewhat cynical subject for children to be writing about, but I couldn’t deny that it was holding their attention. One of the African twins was shy but obviously eager to read his piece. For him, the story of Santa Claus was an example of crao in action. When very small, he wrote, your parents tell you the story, and you believe them, but when older, if you still believe the story, other kids “ils se moquent de toi” (they tease you). You quickly learn to say you don’t believe in Santa Claus, but at home you might

Proud of his essay at La Visitation’s writing workshop. Source: Photo by author.

pretend that you believe in the story. That way you can ask your parents if they think Santa Claus will bring a certain toy you really want. That’s crao too, he concluded, but it helps keep everyone in the family happy.

A slim teenager named Hisham who normally preferred to sketch and draw in his notebook had written a piece he was willing to share. It was a brief meditation on crao in politics. A candidate, he understood, has to make promises about what he or she wants to do for the voters. In fact, these can be candidates one admires and supports. But they really don’t know for sure if they can actually deliver on their promises. Often it will turn out they can’t. So it seemed to Hisham that crao in politics was unavoidable. It also led to people being let down and distrustful of politicians. And that, he concluded, was not even getting to the subject of people and groups being bought by politicians — or, he continued, of constituents buying politicians.

Hisham had been working at a smaller table where Jean and two other boys were also seated, one of whom was the oldest of the three Roma boys. They were setting up a CD player that would play rap beats. The next workshop would be about writing to beats, with a rap artist named Gino, who came from the Panier. Hisham’s short political essay started a discussion of local politics, which I may have pushed a bit with a naive question about local political leadership. A right-wing candidate, Stephane Ravier, had recently been elected mayor of the neighboring Seventh Sector, which included the Fourteenth and Thirteenth Arrondissements. Many had been shocked. How could a former socialist stronghold where there were some large housing estates turn to the right? Jean was not so surprised. Aside from deep political disillusionment among the young, he explained, there were all kinds of animosities to exploit. “Ravier and his people use the latest arrivals, especially the Comorians, as scapegoats [bouc emissaire]. They’ll blame them for whatever issues upset the other groups. ‘They’re coming and taking your privileges.’ All crao.”

Jean talked about Samia Ghali, the socialist mayor of the Eighth Sector, as an exception and a local hero. She represents the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Arrondissements, which contain many of the oldest and most decrepit industrial working-class neighborhoods extending northward from Les Crottes to L’Estaque, clinging to the hills and cliffs just above the commercial port. The sector includes some of the largest housing estates, including La Castellane and La Viste, and many smaller ones, including La Visitation and Cite Bassens, the nearby estate where Samia Ghali was raised by her Algerian grandpar ents. It’s a “world,” she has said to reporters, “that people did not want to see. That politicians did not want to see.”

Samia Ghali is a public voice of that world. As a socialist in the national senate, she often spoke to the needs of France’s housing estates and their residents. More recently, in 2019 she positioned herself to run (unsuccessfully, or, rather, semi-successfully, as we shall see) for mayor by quitting the Socialist Party to form a local party of her own. She has been criticized for engaging in patronage politics in the grand Marseille tradition, but she is a progressive who stands in stark contrast to Stephane Ravier. He has said, for example, that Algeria never should have been granted independence and that the legalization of cannabis is not any different from the legalization of rape, among other outrageous and attention-grabbing utterances. Nonetheless, Ravier became one of the leading contenders in the 2020 citywide mayoral election, which helps explain the political apathy and disillusionment voiced in Jean’s work shop and in the youngsters’ essays about the meaning of crao.

By noon, most of the younger boys were outside, whirling around on scooters or chasing one another through the shaded courtyards of the housing estate. The girls had returned to their apartments to help their mothers. Soon, a couturier workshop would begin. Led by a vivacious clothing designer, it would attract some of the young women and mothers from the buildings. The boys and men needed to be somewhere else. A brilliant blue sky beckoned, and we had been inside almost all morning. Jean suggested that we explore the area around the estate because his group had plans to put in community gardens and expand on the outside murals that were enlivening the halls and walls of the buildings.

La Visitation is located alongside the Ruisseau des Aygalades. Its green vallons account for much of the remaining open, non-buildable space in this part of the city’s northern districts and in the immediate vicinity of La Visitation, but in fact, most residents of the neighborhood would have difficulty identifying the creek in their midst, as it is hidden in ravines, culverts, and drainage ditches. Across the street from La Visitation, the stream extends and winds out of sight behind a huge slag heap. The great heap rises higher than the nearby apartment buildings, a solid remnant of the alumina industry that once flourished in the region. Alumina is the first phase in aluminum production. Its slag is called boue rouge, or red mud, and it contains toxic heavy metal compounds along with sand and gravel. As the mega EuroMed project plans its next phase of development along the avenue des Aygalades, just below La Visitation, the future of the acres of land containing the heap and bordering on the creek remains unknown. I’m told that Roma have camped there, but none were visible on my visits. From time to time, Jean and other activists at La Visitation help curious visitors clamber up to the heap’s broad summit to see what it’s all about. The view of all the surrounding northern neighborhoods and out to the sea beyond is one of the more spectacular perspectives to experience from the city’s northern districts.

A young man named Omar helped me make the climb up the steep sides of the heap. In his early twenties with olive skin, dark eyes, and a wan smile, Omar was a school dropout and semi-homeless. He had talked to me about how much he wanted to find a job…Before COVID, he’d been working as a barista in one of the chic coffee shops in Les Terrasses du Port. This is the grand shopping center, a jewel of the EuroMed project, where many people, not just shoppers, gather to relax and watch the cruise ships and trans-Mediterranean ferries maneuver through the break waters of the commercial port. We would see all that as well from the heights of the slag heap.

After a steep climb, we stopped to catch our breath at the top. We found ourselves on a lush green plateau covered with wild arugula. Our footsteps released its tangy odor. What must have been more recently dumped slag rose from the plateau to form a high mound, an exposed side showing the infamous red mud. The slag plateau must have been at least seven acres in surface area. Beyond it, green open space extended north along the stream’s steep and wooded banks. On another walk along this part of the stream, I learned that there were venerable community gardens, organized by trade unions, and much wild land along the steep banks of the creek.

Omar pointed out some of the larger housing estates: La Castellane, La Viste, La Busserine, and many others. Far to our northwest on the high horizon were housing estates clinging to steep hillsides. Those too, he said, would have local football teams and groups of would-be musicians and rappers. “See that low-rise cité one,” he said, pointing to one nearby, similar to La Visitation in size and density but older. It was Cité Bassens, where Mayor Ghalia grew up. The drug market there, Omar claimed, was as lively as you could find anywhere in the city, but according to Omar there were many other hot spots on the horizon. In fact, La Visitation had been or still was, I was not sure, an active retail drive-in for “shit,” as cannabis was usually called. Indeed, support from the leaseholder and from the state for Jean’s organizing efforts was part of a larger policy of helping local civic groups make their estates safer and more livable.

I was not shocked by the drug situation I found in Marseille’s housing estates. This was because with my research partner, Terry Williams of the New School for Social Research, I had studied kids growing up in New York City in the 1980s and 1990s, which formed the basis for our book, Uptown Kids. Many of the same (or far worse) had prevailed. In Marseille and other major French cities there had never been a full-blown crack epidemic; nor, with a few exceptions, are there violent youth gangs. Aggressive turf defense and warring gangs are more an American story. Marseille is still the town with the scruffy joie de vivre and spirit of tolerance that Claude McKay discovered and loved in the 1920s. Young people from housing estates like La Visitation circulate through most parts of the city without fear — if they have the carfare.

I was more interested in understanding the history of the slag heap and in exploring green possibilities along the wooded stream banks of the Ruisseau des Aygalades than in hearing about local drug markets…

As we clambered down from the slag heap that afternoon, I vowed to come back and explore the area again. I wanted to know more about the community gardens and the old grave yards, the limestone grottos, the waterfall, and the restoration possibilities for the deindustrialized and toxic sections of Les Aygalades.

Back at the Local, I joined Jean, Christiane Martinez, my friend the organizer Quentin Ambrosino, young Omar, and the muralist Vince Landry for coffee. We talked about how much could be done to upgrade the buildings and the surrounding areas. However, the slag heap’s destiny seemed too much for them to contemplate. Toxic red mud had a bad reputation. I stared out the window toward where the slag heap loomed above the buildings, but my reverie was shattered.

A teenage boy I had never seen ran past the window. He was carrying what was unmistakably a Kalashnikov. No one had seen him but me. I was rattled but tried to keep my cool. Maybe it was a toy, I thought. “Jean, I just saw a kid with a machine gun. Was it real?” He looked at me with something of a sorrowful shrug. “Maybe yes, maybe no.” I took that to mean most likely yes. We parted on that blue note. Jean accompanied me as I waited for the bus to arrive to take me to the subway at Bougainville. Despite his warm companionship, I felt the chill of life’s fragility.

MARSEILLE/NEW YORK

In the fall of 2019, a few months before the pandemic struck, I invited my young Marseille friends to come for a New York visit: Jean Sylva of We-Records and La Visitation; Vince Landry the artist; and Alexander Arnoux-Pierre, an inspiring Montreal community organizer often with Jean and the crew in Marseille. I looked forward to showing my young friends the city of my birth in exchange for all they had done to help me know their Marseille. But I also had a more specific agenda: I wanted to make a pitch for ecological restoration. I hoped to bring our conversation back to the slag heap along the Ruisseau des Aygalades, across from the La Visitation.

It had been seven years since I had begun to try to decipher the neighborhoods on Marseille’s north side, seven years since [I’d been introduced] to Jean Sylva and Christiane Martinez and the folks at La Visitation. In that time, the group of artists and activists Jean attracted around We-Records had worked closely with allies in government to expand their activities. They had produced some exciting public art in and around the buildings at La Visitation. They were working on using converted containers as outdoor classrooms to expand on the space available beyond the Local.

I hoped to sell them on the idea that the slag heap could be turned into a public park that would be a benefit to local residents and others. My plan was to show them some examples in and around New York. My friends were staying with us in Long Beach, a beach town on the Atlantic Ocean beyond Kennedy Airport.

The morning after their arrival came up chilly with bright sun. Of course they were eager to get into Manhattan, but first we headed for a park near the neighboring town of Freeport, Long Island.

These towns on the extreme southern shore of Nassau County are within an ecosystem of wetlands and barrier islands that covers much of the South Shore of Long Island, including the Atlantic coasts of Brooklyn and Queens, as well as the entire seaward-sloping East Coast of the United States below Cape Cod. In my particular tidal flats and marshes, their preservation depends on the parks and parkways created in the 193os by Robert Moses, the region’s “master builder.” The park we were headed for, however, was a far more modest achievement than Jones Beach State Park but perhaps no less inspiring.

“It’s a park recycled from an old garbage dump,” I said. We parked the car at the entrance, on what are the Merrick, Long Island, sanitation grounds. Merrick and Freeport are suburban towns on either side of the Meadowbrook Parkway-about twenty minutes of driving through scenic wetlands from where we were in Long Beach.

“I never thought about New York this way,” Vince Landry commented through his jetlag, “that there was so much water everywhere.” Nor did I, as a newcomer, have an image of Marseille that included the complicated northern neighbor hoods with their diverse cites and industrial-age village centers built along roads and streams descending over aygalades and through vallons. “Cities are much more than what goes on in the center,” I said, squelching the lecture reflex.

Jean was just taking it all in, not saying much but listening intently. My friends would not have known they were walking on a former refuse heap had I not explained where we were. Walkers, joggers, and the occasional runner passed by on the wide crushed-shell path that mounted gradually up the side of the fully reforested mound. Through the trees we made out a brackish creek lined with phragmites and cattails that runs along the base of the mound. Eventually it dives through a culvert under the parkway into a larger channel in the wetlands. The walk up the sides of the former heap is about two miles. My boyhood friend Philip Oberlander had come along to meet the young men, and since he grew up in Montreal, he speaks French. Phil and I set a slow place up to the summit.

Norman J. Levy Park is named after a state legislator and dedicated environmentalist from the area who was instrumental in obtaining funds from the state to build the park. But the unsung hero of this park was a local resident, Mr. Jay Pitti. A gardener and landscaper, he often drove his truck to the top to dump debris and cuttings. Over the years the mound grew, and the view became ever more compelling. “Merrick disappears. Freeport disappears. Now, you see the greater dimension, the planet, nature. Hopefully, people will be able to visit this site and enjoy nature, at its visual best, and hopefully con template the need to respect that nature,” said Mr. Pitti to a local reporter in 2000 at the park’s opening, when he was sixty-seven.

When it was closed as a dump in 1986, it had reached a height of 120 feet above sea level, the highest point on the southern shore of Long Island. (Most other places, including our house in Long Beach, are an average of six feet above sea level.) Mr. Pitti formed a committee of about twenty other locals, and for about sixteen years they developed a vision of the park and lobbied elected officials for its creation. And here we were reaching its top.

Suddenly there were 360 degrees of dizzying geography: South to the Jones Beach tower and the ocean whitecaps, east across the wetlands with their meandering channels, west across, the plains of suburbia to the skyline of Manhattan on the horizon. My friends were impressed. I argued that it was not a lot different in many ways from the view of Marseille and the ocean shores from atop the slag heap on the boulevard des Aygalades.

Nor is it only the view that matters in this “nature” preserve. The top of the park is a plateau with two sizeable freshwater ponds circled by the broad walking path. A tall windmill pumps water from the stream below and creates a welcoming landmark for the cars speeding by on the Meadowbrook Parkway.

A herd of friendly black goats, about twenty in all, trim weeds and attract children. The goats sleep at night in a barn at the park’s entrance because red foxes have lately moved into the neighborhood. Of course there are birds galore, mostly ducks and geese, drinking and feeding in the ponds. Below the surface of the park mound there is still a lot of decomposition going on. Methane exhaust pipes with tin hats stand like slim sentinels at regular intervals behind the paths.

My friends saw immediately what I was getting at. I don’t think they were prepared to become environmentalists in a more abstract sense, but that did not matter. “You know, Jean,” I said, “You don’t have to be committed to years of organizing like Mr. Pitti. I’m showing you this because I think the slag heap on Les Aygalades is an important issue. It could be something new for your neighborhood. If you guys put it out there on the public agenda, call attention to it, create your artistic vision of what it could be, you might be surprised at what happens.”

Indeed, that is exactly what they did, with results that were surprising to everyone. But that took place when they returned to Marseille, and it is one of those ongoing stories of our two ports. At that moment, they still had a lot of New York City to explore.

Jean Sylva had recently lost his mother and was grieving over her loss. He was most interested in going to a church service in Harlem. On the Sunday of their visit, my friend Jacquelyn Oberlander graciously invited them to a service at her church in Harlem. They sat in a regular pew among her Harlem neighbors, not in the tourist section in the balcony, and were treated to an inspiring sermon by the new female pastor.

Vince wanted to see some contemporary art at the Whitney and walk the High Line, another recycled park. Alexander was familiar with the city, as he had relatives there, but he was taking a lot of pleasure in showing his friends some of the city’s nighttime sights. I had set up a public meeting for them about Marseille in my former institution, the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, on Thirty-Fourth Street, right across from the Empire State Building. They spoke there to a friendly academic audience about their Marseille community projects. Coincidentally, Professor Ken Brown, of Noailles fame, happened to be working for a few weeks again in the city and joined us for the discussion of Marseille politics.

Another Manhattan day we visited the studios of Rock Paper Scissors, a bicoastal video and film production company managed in New York by my daughter Eve. Her offices are on Twenty-Eighth and Fifth, overlooking the Flatiron Building, which Vince knew as an early gratte-ciel, a skyscraper. Large photo portraits of the Brooklyn rapper Biggie Smalls hung near the elevator that opens on the floor. Biggie made them feel they had come to the right place. Earlier, in 2015 Eve had helped me create a YouTube video about La Visitation and Jean’s Local that had drawn some favorable attention to their We-Records work in Marseille.

On one of those brilliantly bright New York fall days, when the freighters anchored five miles out in the ocean off Long Beach are visible in high definition, I took my Marseille friends on a car ride along the Belt Parkway. We would ultimately stop in Dumbo, the neighborhood underneath the Brooklyn side of the Manhattan Bridge. We’d stroll along the East River at sunset, across the water from the Statue of Liberty, one of the quintessential New York photo ops.

As we crossed the Atlantic Beach Bridge into Far Rockaway, the mood in the car was subdued. There was classical music on the car radio. I switched the playlist to some classic rap from the Wu-Tang Clan and Biggie Smalls. Instantly the car was jumping. My young French friends knew most of the English lyrics. They began coming in on the beats with the tribal hoots and toots of the hip-hop world. Rap tunes became the day’s soundtrack. It didn’t matter if we were driving through the public housing estates of the Rockaways or cruising under the Verrazzano Bridge, the hip-hop beats seemed the perfect soundtrack for every locale.

My first stop was with the birds at the famous wildlife preserve on Broad Channel Island, where the avian world congregates under the flight pattern of incoming jumbo jets. Managed by the National Park Service as part of Gateway National Recreation Area, it’s another citizen-initiated recycled park. Two large freshwater ponds created by reforested landfill berms sit on what were once much-abused wetlands. The freshwater attracts birds of all species and birdwatchers with every kind of lens one can imagine. Ducks seem not to be able to stay away in all seasons. Thousands of New York school kids by the busloads are taken here to learn about the natural habitats of the city they inhabit. I’m proud to have worked on this first urban national park with many of my students at its creation, in 1973.

Again, this was an unexpected visit for my friends. Vince Landry’s vision of the city had been far more vertical and hard-edged. Jean Sylva was taking it all in as always. He had already caught on to what I was after. Looking across a prairie of spartina marshes and expanses of bay, I showed them Floyd Bennett Field, the recycled naval airport, now another public part of the Gateway park system. In the far distance, the Manhattan skyline glimmered as only it can. We were getting hungry. The obvious solution was to hop in the car and head for Nathan’s in Coney Island.

My mother’s family lived in Coney Island during much of the r92os. My father played sandlot baseball in nearby Marine Park and at Manhattan Beach. They met through mutual friends and courted on the rides and in Feltman’s, the German beer garden, before the great fire in 1932. Among my earliest memories is the terror I felt when first going down the giant indoor slide at Steeplechase Park. It’s a fabled part of the city, and the original Nathan’s, home of the Coney Island hot dog, remains its most celebrated eating arena.

After lunch at Nathan’s, the endless boardwalk had a strong hip-hop vibe, with murals galore and zooming skateboarders. “Le Brooklyn” is hot in France lately, as young French visitors venture outside Manhattan to find what’s happening in the city’s (somewhat) more affordable communities. But it’s a vast borough: our windshield survey that day covered the ethnically dizzying length of Flatbush Avenue, with stops at the leafy campus of Brooklyn College, a peek into Prospect Park, and coffee in Williamsburg. By the time we reached the Brooklyn Bridge, the sun was getting low in the western sky. We ambled along the river through the new park areas that have replaced the old Port Authority commercial docks. Vince took some selfies. I rested and did stretches on a bench while Vince and Jean took more photos. Jean had to crouch almost to the ground to find a proper angle when an Asian couple asked them to take their photo with the Brooklyn Bridge and the East River in the background.

Across the river in Manhattan, it was full rush hour. Red sunbeams flashed on the buildings and on the green copper tower of the Municipal Building, where my father had worked and where, as a boy, I looked down into the river at the tugs towing barges of coal and cement under the bridges.

“It will be part of your monument,” my father had said to me with a wink, a few years before his death in 1979. We were walking on a runway at Floyd Bennett Field, in Jamaica Bay, talking about what it might be used for in its future as an urban national park.

“What kind of monument do you mean? I work on teams inside bureaucracies. I’ll never be on any monument.”

“Neither will I,” he said. “Neither will anybody we know. The city is our monument.”

Sure enough, when my friends returned to Marseille they organized a press conference about the possibilities of ecological restoration at the slag heap. The 2020 mayoral elections were heating up. Elected officials took notice. Their meeting was attended by some of the candidates, including Samia Ghali. Jean Sylva’s monument to the city he loves may be a park on that slag heap across the avenue des Aygalades, in the neighborhood of his Marseille childhood. We’ll try to get back there as often as possible to help things along.

***

Reprinted from the Marseille: Port to Port (Columbia University Press, 2022), by William Kornblum, with the permission of the author.