(Gaza Feb 29 2024)

A small grey rectangle

The aid truck arrives

Iron filings converge upon a magnet

Ants swarming a dropped chocolate

They may have weapons

hidden in their skeletal hands

Their hunger may be explosive

A Website of the Radical Imagination

(Gaza Feb 29 2024)

A small grey rectangle

The aid truck arrives

Iron filings converge upon a magnet

Ants swarming a dropped chocolate

They may have weapons

hidden in their skeletal hands

Their hunger may be explosive

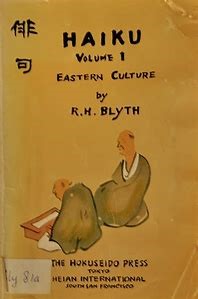

I found the first book of R. H. Blyth’s four volume set, Haiku, (originally published between 1949-1952) in a used book store on St. Mark’s Place. If haiku seems no more pertinent to you than, say, heraldry—one more subject about which even an informed person “need not be ashamed to know nothing”[1]—you may be mollified to hear I had an excuse to check Eastern Culture since I was Christmas shopping for a nephew who’s on his way to Japan this spring. The book’s cover—“Oriental brown simple rough peasant cloth”—got me to open “the Blyth Haiku bibles” (pace Allen Ginsberg, Allen Ginsberg). I fell in…

“Plop!”

To quote the last line of “the most famous haiku” with frog-and-pond as translated by Blyth—scholar-gypsy who brought the East to Beats and Salinger (see J.D.’s bow to Blyth in “Seymour, An Introduction”: “…haiku, but senryu, too…can be read with special satisfaction when R. H. Blyth was on them. Blyth is sometimes perilous, naturally, since he’s a highhanded old poem himself, but he’s also sublime.”)

Dedicated to him, whom I regard “as the very master of that working corps who would restore to rectitude the warped system of things.”

We have a great deal of critical writing on Victorian novels—the grand products of George Eliot, Charlotte Brontë, William Makepeace Thackeray, et. al.—but not as many accounts of how readers come to read these novels. In 1979, an entire cohort, especially of women, would have pounced on Jane Eyre after reading Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s fetchingly titled feminist study The Madwoman in the Attic. At that time, I was otherwise absorbed (incidentally, like the heroine of Jane Eyre) in reading classical German literature. But now, nearly half a century later, I am with Jane, struck by its power and beauty.

This is a chapter from Blyth’s first book, Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics.[1]

…

From Aristotle down to Arnold it was considered that a great subject was necessary to the poet. Arnold says that the plot is everything. It is useless for the poet to

imagine that he has everything in his own power; that he can make an intrinsically inferior action equally delightful with a more excellent one by his treatment of it.

Wordsworth stands outside this tradition by instinct and by choice. He chooses the aged, the poor, the idiot, the vagrant, but does not endeavour to make them “delightful” at all.

Spooning, our dog and cat doze in the sun.

Tails twitch and amber eyes close in the sun.

why do it in poetic form?

because in an infinite variety of ways

that reside in the breasts of all living souls

any solution to the Fascist trend in all states

pulses and grooves inside each of us

we hear the basic call of consciousness & conscience

An essay in last month’s Town Topics, a Princeton gazette, begins on target: “This is an anniversary year for Franz Kafka, who died on June 3, 1924—a doubly noteworthy centenary, given the immensity of the author’s posthumous presence, which suggests that if ever a writer was born on the day he died, it was Kafka.”[i] Given that “immensity of presence,” one would be hard put to define concisely its core significance. But I will attempt to get to that core by example—the core being the difficult beauty of Kafka’s writing, a beauty that is full of thought, and which has inspired, as is well known, a great variety of attempts to understand it. For Theodor Adorno, in a celebrated essay, satisfying the need to understand Kafka is a matter of life and death!

Hope sparked by a bright field. Sorrow, the woods.

We caution children, Don’t go in the woods.

I have been reading and writing poetry ever since I was a boy growing up in Huntington, Long Island, not far from where Walt Whitman was born and raised, and where he founded the newspaper, The Long Islander, which published my column on high school sports. At the age of 82, I still turn to poetry more often than to newspapers for news of the world, local, national and international. Recently, I read and reread the timely and (perhaps) timeless poems about Gaza in Mosab Abu Toha’s Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear, published by City Lights.

That book appeared in print at about the same time that the author and members of his family, including his wife and children—and thousands of other Gazans—were detained by Israeli soldiers. Fortunately, Toha’s wife and children were released and allowed to travel to Egypt where the poet joined them, and then wrote and published an eye-opening account of his own harrowing arrest, incarceration, and interrogation. That narrative was published in January 2024 in The New Yorker. In a short time, it has alerted readers around the world to Toha’s poetry and to his own newsworthy story.

I

…If you were a goddess, Xylea said, what goddess would you be? She paused to think for a second. If you were a goddess, you’d be the goddess of beauty and illusion…

…That haunted me, for some reason. The reason was that my life had, without my noticing, been drained of reality, or the pretense to reality. I was a celibate, anhedonic whore (let’s say a depressed whore). Sex itself meant nothing to me, having become mere performance, empty enchantment. I fell in love with ghosts, or people who soon became ghosts, whose names I no longer remembered shortly afterwards.

He chose friends for wit, his bride for beauty.

She always erred on the side of beauty.

Punk soul in a Father’s body, Hopkins

wrote the motley an anthem –- Pied Beauty.

Mary Oliver’s speaker walks with awe

through the world. Dickinson’s died for beauty.

“From the inside.” “Eye of the beholder.”

Well-meaning parents lied about beauty.

The author emailed this response to Leila Zalokar’s December 1 post, “Planet X,” under the heading, “Awesome.”

Starts with a bang! [couldn’t help myself]

And right off the bat, I can’t think of a word, but that melancholy, ironic, hopefulness(?)

…still, the desire to fuck / morning cigarettes…

You

make me taste your

……………….vastness on my tongue

then dismiss me

one of many loved

……………….beneath the belly of the sun

Fate

If the Fates come to take

those I love, bear witness to this —

………………………..they will not be victims

………………………..of what the ignorant, or,

………………………..perhaps, the grieving,

………………………..call terror.

……………….

Rockets fly into neighbors’ homes —

………………………..tonight? Tomorrow?

……………………….My own home?

If the Fates come for those I love,

I will not wrap them in white sheets,

lay them at the door of the man

who forced this war. He will not see us.

And if the Fates come for me, well,

there is no wrong in dying. But

bear witness, bear witness to this —

……………………………………I am not killed

……………………………………by a foreign hand.

……………….

Israel. Gaza. May 2021.

1.

Like soft yellow clouds speckled in brown,

the Masai giraffes cross the Kenyan safari.

I was a giraffe once, too, in my mind,

even though I was the shortest in my class,

hanging on to high branches

to be nourished from above—

my imagination, books, arts.

On the earth, lonely, not matching my classmates,

vigilantly searching from my distance after possible dangers.

A child in the Ramat Sharet elementary school in Jerusalem

with her head up in the mountains of Africa,

reading repeatedly ‘Lobengulu King of Zulu’ by Nachum Guttman.

“It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet…”

What follows are two poems from J’Accuse (New Directions, 2003) by Aharon Shabtai, translated from the Hebrew by Peter Cole.

..Still, there’s the desire to fuck.

..There’s morning cigarettes.

..There’s the sun, post-orgasmic, after the death of all superstructures and erections. The shade cum sliding down her thigh earth night secret smile sleep dark no dream

..Pearls and scars

..A few more good poems to read, fewer still to write.

..The collapse of empires, master races, meta narratives, ethical sadomasochisms, bourgeois psychology, teleology of hope.

..There’s no need to rebuild anything.