Bill Berkson, who died of a heart attack last Thursday, had only recently begun posting at First of the Month. But he already felt like part of First’s virtual family. He got close to my real family too.

Culturewatch

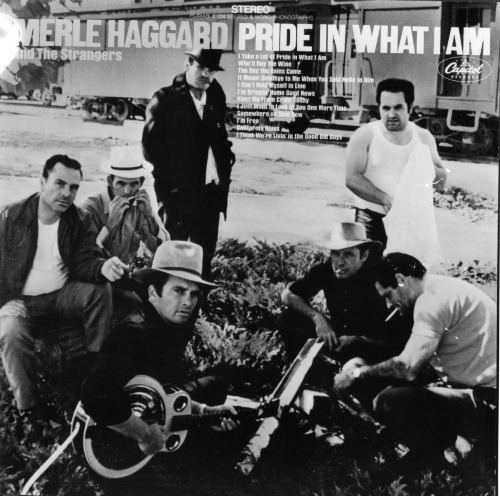

The Punk/Country Connection & Merle Haggard

Jon Langford of the Mekons goes back to the roots of his British Punk band’s feeling for hard country music before memorializing Merle Haggard.

Merle Haggard R.I.P. (“I Take a Lot of Pride in What I Am”)

Merle Haggard was probably the greatest singer-songwriter I’ve ever seen. The only artist I can think to compare him to is Sam Cooke, who like Merle possessed the gift for writing songs that were at once both deeply personal and universally applicable to the human condition.

Merle Haggard was probably the greatest singer-songwriter I’ve ever seen. The only artist I can think to compare him to is Sam Cooke, who like Merle possessed the gift for writing songs that were at once both deeply personal and universally applicable to the human condition.

Sixties Trips II

Part two of an essay that begins here.

Richard Goldstein’s approach to the sixties was shaped by his sense “race was at the core of nearly everything.” But his lucidity about race matters is most evident when he’s writing about “revolution.” As rock ‘n’ roll turned into rock, Goldstein’s pop life got whiter.

Albuquerque Girl (Show Me All Around the World)

The author of the following sweet treatment of an anti-Trump protestor realized she needed to fill in the surreal background from which a very real girl had emerged:

Black night in the city and police water hoses and smoke backlit. But almost lazily done by cops, just as any breakage by bare chest kids was momentary and quick. But it was a funny setting for her, so lively so in her life…

The Greatest Gone…Ali in Four Movements

I can’t remember when I first heard of Muhammad Ali. It seems like he’d always been a part of my life. I knew this: my father loved him so therefore I did as well. (The same went for Frank Sinatra, Afro-Cuban music, jazz, the New York Mets and our home borough of Brooklyn.)

The Flight of the Somebodies

A version of this essay is included in Bob Levin’s Cheesesteak – his new “rememboir” of “the West Philadelphia years.” (There’s information on how to buy his witty book of Philly wonders at the end of this post.)

In the late 1950s, when I was in high school, two Negroes joined the periphery of my social crowd. Edward played piano and Lester bass, and they were jazz musicians. They never had gigs and, if they did, the gigs never paid; but that is who they were, and that is what they did. If I or Max Garden or Davie Peters had a car, we gave Edward and his bass a ride to their rehearsal. If you had a piano, that rehearsal might be your living room.

Both Lester and Edward were built slight, spoke soft, and dressed Ivy. But it was Edward, still in his teens, who became through Robutussin AC the first druggie I knew. And it was he who, when asked if he was going to college, uttered the line I fed a minor but weighty character in my first novel: “What, man, you mean be a everybody?”

Sixties Trips

“WHERE CAN I GET MY COCK SUCKED? WHERE CAN I GET MY ASS FUCKED?” Mick Jagger’s second pass at the chorus of “Cocksucker Blues”—and the feral moan that launches the track—“I’m a looooooonesome schoolboy…” seem to echo Richard Goldstein’s line in his new memoir on why he identified with rock stars (and girl groups) who started out with him in the 60s: “they were as hungry as me.”

Phenomenology of Everyday Life

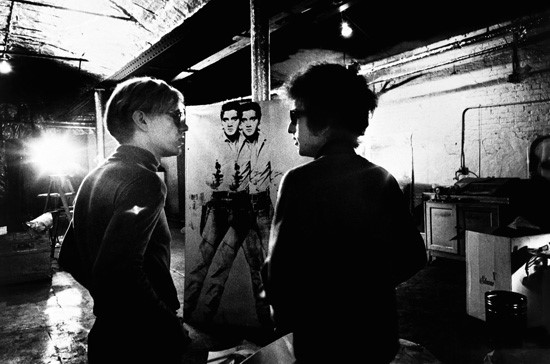

The Phenomenology of Everyday Life, the unbranded brand of impromptu activity, proto-YouTube, beginning around 1960, of documenting anything and everything, the less obviously consequential the better, extended from a disposition toward collecting oddments (from baseball cards to bottle caps) gathered before, in the 50s, and likewise had a lot to do with recording devices. Somehow the record keepers have never gathered the strands––and no one yet knows the full import––of the sundry manifestations, in visual art, writing and general culture, of this passion to look, listen and record.

Czechmate

The following Q&A is an excerpt from an interview with filmmaker Agnieszka Holland originally published at Director Talk. In this section of the interview Holland talks about the Czechs’ response to the Soviet invasion in 1968, the subject of Burning Bush, a three-part HBO miniseries directed by Holland.

Counter-Insurgency Preceding the End of the World

The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘state of emergency’ in which we live is not the exception but the rule. We must attain to a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight. Then we shall clearly realize that it is our task to bring about a real state of emergency, and this will improve our position in the struggle against Fascism. One reason why Fascism has a chance is that in the name of progress its opponents treat it as a historical norm. The current amazement that the things we are experiencing are ‘still’ possible in the twentieth century is not philosophical. This amazement is not the beginning of knowledge–unless it is the knowledge that the view of history which gives rise to it is untenable. –Walter Benjamin

Paul Feyerabend—a half-forgotten Calibanal apostle straddling the right-wing Vienna side of European modernism and California anti/pseudo-science counterculture—was shot three times by the Red Army while retreating from the Eastern Front. His injuries left him neuralgic, prone to a particularly (in/post-)fertile depression, and impotent.

The Heart of the Matter

Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 by Adam Hochschild, Macmillan, 2016.

How is it that after so many years and so many wars and so many revolutions, counter-revolutions, assassinations, genocides, and betrayals, the Spanish Civil War continues to capture the imagination of idealists and romantics?

The Man with the Purple Guitar

For a long time, my image of the Ugly American was a thick-necked Prince hater I met (early in the Age of Reagan) when he drove me around the Upper West Side as I delivered Christmas gifts for a package store. This piece of work (who had a familial connection to the owners and wanted me to know he was tight with my bosses) had seen Prince open for the Stones in 1981. He’d been among thousands in the overwhelmingly white crowd who booed the “faggot” unmercifully.

The Working-Day

Work is what is on the other side of sleep. It is everything I do when I’m awake.

Currying Favor in College Ball

I. Anticipation

With the NCAA tournament (March Madness) beginning only two days after the high school team I help coach was eliminated from the California state tournament, I figured I’d finally have a chance catch up on what’s happening with college ball. After all, even with the NCAA’s being increasingly exposed as The Evil Empire, c’mon, ya hadda love college ball. If you knew anything at all, you preferred it to the NBA, scorned those who did not. But not in the newly-dawned Steph Curry Era!

George Ohr: A Free Man in Biloxi

“I love George Ohr. More freedom in his head then in just about anyone’s.

Ohr was a 19th century ceramic futurist. Looking at his work rubbing my fingers together, thinking about the feel of wet clay. his mind must have moved like clay moves when you throw it on a wheel or pinch it…it always seeks freedom…the potter seeks control…the dance is between the authority of the material and the will of the potter. It can be a discussion or a debate. A lot of talking.”—Michael Brod

Brod’s musings prompted your editor to ask him to say more on George Ohr, “mad potter of Biloxi,” (who surely looked the part—see the photo at the bottom of this post). Ohr, himself, was more than willing to think out loud about his works and days: “I brood over [each pot] with the same tenderness a mortal child awakens in its parent.”[1] A few of Ohr’s numberless creations were exhibited in NYC last year at the Craig F. Starr gallery. These three were in that show. (You can find many more examples of Ohr’s art pots here.)

Minds of the South

It is, by now, well known that Atticus Finch, beloved hero of the late Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, is revealed to be a segregationist in Lee’s recently published novel Go Set a Watchman.

Group Grope: The Theory of Microaggression

Eugene Goodheart has invited responses to his new First piece (posted below) which takes in student protests against microaggressions and the more macro analysis of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me.[1] I’m skeptical of Goodheart’s attempt to hook-up the world-view of those students with Coates’s World. (More on that anon.) But his critique of the protesters has pushed me to think through the theory of microaggression.