Culturewatch

Max Raphael: A Creative Life in Struggle

Some fight because they hate what confronts them, others because they have taken the measure of their lives and wish to give meaning to their existence. The latter are likely to struggle more persistently. Max Raphael was a very pure example of the second type.

That’s the opening passage of John Berger’s tribute to Raphael whose Marxist scholarship and theories on the practice of art made him, in Berger’s estimation, the “greatest mind yet applied to the subject.”

Bibliotherapy

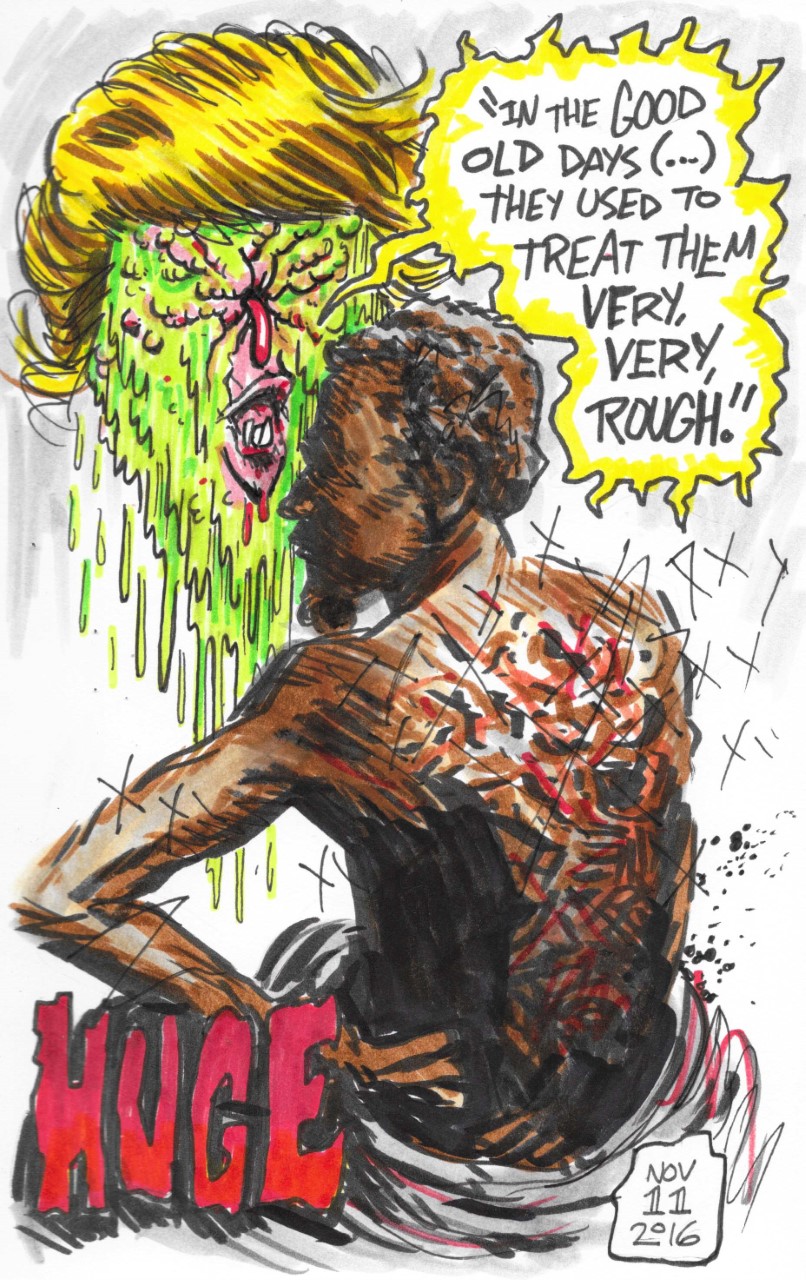

Angry Young Men—today the concept in its simplicity seems quaint, almost charming. Among millennials, there’s an underground subset of young males wrecked amidst the storms of self-creation and signification. The internet is now nearly the exclusive domain of social and cultural life. For many born without memory of life before the web, there burn weird heart-fires of grievance and resentment, imbued with the alien green hue of nocturnal computer monitors. How to forge an identity out of an endless succession of ironic poses?

Whip It To Me

The death of Debbie Reynolds moved Laurie Stone to muse on Facebook (and in an email to your editor).

Merry Christmas from Kevin Durant and Draymond Green

The monetary and the military

They get together

Whenever it’s necessary

They’re making the planet into a cemetery.

—Gil Scott-Heron

Christmas Day, and did I need a gift! Feeling—ever since Elektion Day as if I am living somewhere between under a dark cloud and in a ratcheting-up concentration camp, I thought maybe I could still derive some pleasure—if not solace—from the long-anticipated NBA Finals “re-match” between Cleveland and Golden State.

Two Joes and a Jill

On December 12, 1942, The New Yorker published a 7000-word profile, entitled “Professor Seagull,” by Joseph Mitchell. The subject was Joe Gould, a 53-year-old Greenwich Village eccentric, who was said to be writing an “Oral History of Our Times,” consisting of a record of conversations he had overheard over the last decades and essays related to these conversations. It was, Gould claimed, several times the length of the Bible and, most likely, the longest book ever written.

Irrevocable

During the last years of her life, Diane Arbus visited institutions for the mentally ill to photograph the residents, people often physically as well as mentally disabled. I remember being repelled by these photographs, and gathered that Arbus had by now crossed a line in her own mental state, becoming engulfed by a spiritual/emotional darkness from which she would never recover. She committed suicide by slitting her wrists in 1971 at the age of 48.

I happened to come across a French edition of the photographs while I was reading Diane Arbus: A Chronology 1923-1971 and they didn’t look the same. Arbus writes in A Chronology of the gossamer quality of the light in these images, which were taken mostly outdoors at sunset, and the photographs now seemed suffused with the deepest tenderness. It’s as if Arbus is photographing the soft underside of the human psyche — the pre-rational child that can scarcely navigate. It isn’t a pretty picture except that it looked now like only another natural part of the whole operating system of reality, including the light in which she finds it.

Love in the Western World

“I have a confession,” he said to his wife. The children were watching something in the other room. A cooking show. A cooking show about cupcakes. “I am besieged with artifacts and associations and they are cluttering my mind to the point of not being able to function.”

“Does that mean you are ready to throw them out? Because they are cluttering the house.”

“Let me tell you about one of them, ok? An artifact in my head. One example. Then we can see.”

Prodigal Fathers

Fathers are universal. We’ve all had one, and some of us have had more. In my case I had the same one three times. By that I mean…Well, maybe I ought to start from the beginning.

Like, A Prayer

“To the victor belong the spoils!” That was Camille Paglia’s reaction, reported in a May Salon article, to what she referred to as “the sexiest picture published in the mainstream media in years”—a photo showing a besuited Donald Trump looming possessively over his seated date at a banquet in the early 90s, his pendulous necktie practically tracing the word “phallus” in the air for the benefit of all easily impressed onlookers. Paglia apparently being one of them, although she wasn’t invited to the banquet—for her, the tie is a “phallic tongue” and Trump resembles “a triumphant dragon,” his “spoils” worthy of Rita Hayworth comparisons.

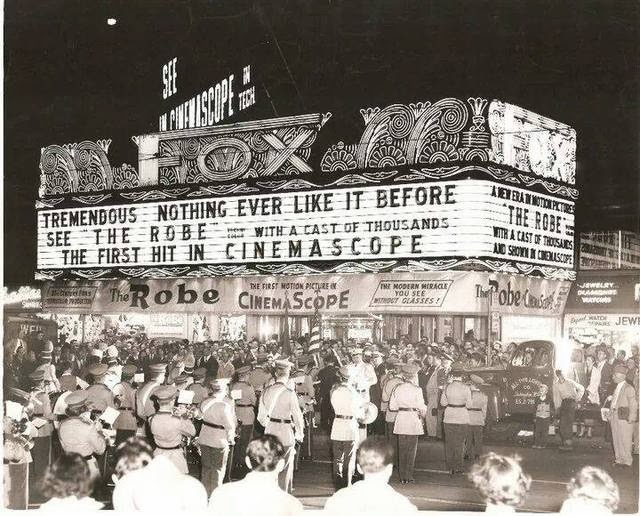

Top of the Fox

They tore down the Fox Theatre on Market Street in Philadelphia in 1980.

Overkill

Hard to argue with lefty sportswriter Dave Zirin’s point that players should be free to determine their own venues, but Kevin Durant’s move to the Warriors strikes at the heart of what makes professional sports interesting; dare I say “worthwhile”? Competitive balance and team cohesiveness.

His Blood-stained Hands

In the moments before Donald Trump announced his choice of running mate, Vox’s Ezra Klein told us, reporters found themselves staring at “an empty podium and the Rolling Stones blasting through the speakers.” What was the song chosen for this momentous occasion? “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” The song has been background noise for Trump’s rallies for months, even though the Stones asked the candidate to cease and desist back in February. What is it doing there?

Borderline

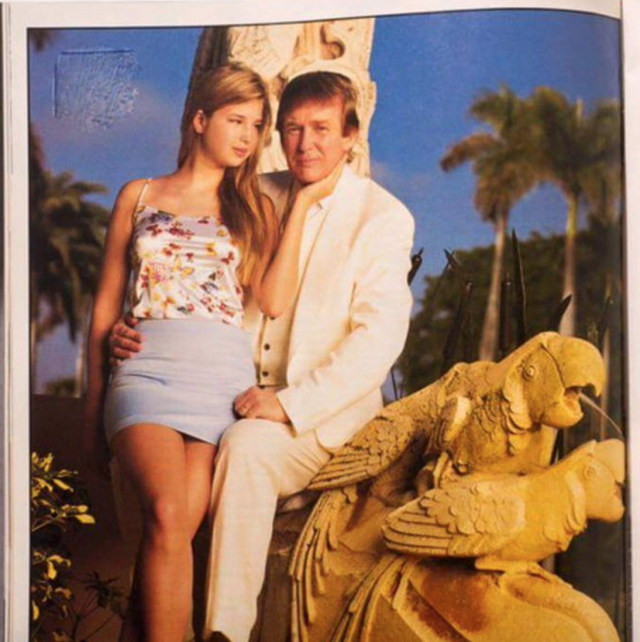

Donald Trump and his (then) 15 year old daughter, Ivanka. From a 1996 Vanity Fair photo shoot.

Donald Trump and his (then) 15 year old daughter, Ivanka. From a 1996 Vanity Fair photo shoot.

Humanist on the Bridge

Pierre Ryckmans (1935 – 2014), who also used the pen-name Simon Leys, is best known for his trilogy of truth attacks on the Cultural Revolution in China and the mindlessness of Maoism—Les Habits neufs du président Mao (1971), Ombres chinoises (1974) and Images brisées (1976). Ryckmans came to be known as the Orwell of the East and the revelations of Ombres chinoises (Chinese Shadows), in particular, are worthy of Homage to Catalonia.

Ryckmans’ mind was as rangy as Orwell’s. His variousness and lucidity are on display in his ABC Boyer lectures, which he gave in Australia back in 1996. What follows is a transcript of his opening talk on “Learning.”

2016 is Taking No Prisoners, Part 37: Twelve Rounds on Ali

Round 1: Having acknowledged the futile challenge of having to write an original introductory sentence for an essay about a man who is literally the most exhaustively written-about figure of our lifetimes, I refuse to step forward and take it on.