Thanks to the script and Edward Norton—a real actor with a larger palette than Timothée el blanco—Pete Seeger is a central player in the new Dylan movie. Part of being a so-phisticated 9-year-old in 1965 (rather than a winsome seven-year-old sing-a-longer con hammer) was to lean away from Pete Seeger. Down the line, when I got all clear about the history of America’s Fellow Travelers, my aversion to him went beyond his/my square past. Every time some Oliver Stoney/Nationist upholds some update of Stalinist/Putinist nonsense, I want to curse all the fuckers who polluted the American radical imagination with agitprop about humanism of totalitarians. Seeger was tuned to their channel for way too long. Unlike so many of his comrades, though, he got free (if not loose)…

Culturewatch

Let’s ‘ave a Larf (“In which I introduce the Beatles to both Bob Dylan and the evil weed…”)

Before (the late) Al Aronowitz brought Dylan and pot to the Beatles, he introduced Billie Holiday to the Beats. You can read his sweet tale about that encounter here. I’m reminded just now that I met Aronowitz one evening in the aughts at Amiri Baraka’s house where a tiny group had turned out for a poetry reading by an ex-member of The Last Poets. The odd few included the current mayor of Newark, who chowed down with me in the kitchen as someone’s (Amina’s?) beans moved his dad to get rhapsodic. Wish I’d taken Baraka’s words down. His offhand ode to beans was as tasty as Seven Guitars‘ melody of greens. Thankfully, though, I recall what happened after the reading when the Last Poet let on he’d become a Muslim. Baraka’s response was to pour the Courvoisier and ask: “Is God a tease? How come this is so mellow if He doesn’t want us to have a taste?”

On to Aronowitz’s (conflicted) case for natural highs…

It’s my experience that to smoke marijuana for the first time is to explore the limits of hilarity only to find that there are no limits. You laugh so hard that you get addicted to it. You want to laugh that hard again, so you smoke marijuana again. And again and again and again and again. I’m told that few ever really succeed in laughing that hard a second time, but I did. The two biggest laughs of my life were the first time I smoked marijuana and the first time the Beatles smoked it.

The latter occasion was at the Hotel Delmonico on Manhattan’s Park Avenue on August 28, 1964. The Beatles and their manager, Brian Epstein, had just finished eating their room service dinner when Bob Dylan and I pulled up in Bob’s blue Ford station wagon driven by Victor Maymudes, Dylan’s tall, slender-and wiry Sephardic-looking roadie. Victor carried the stash in his pocket as we made our way through the mob of teenyboppers on the sidewalk and into the hotel.

Bob Dylan: On A Couch & Fifty Cents A Day

Peter McKenzie’s parents welcomed Bob Dylan into their life and New York City apartment where he slept on the couch for a couple seasons in 1961. Mac and Eve McKenzie helped introduce Dylan to Greenwich Village’s politics of culture. Peter was in high school (on his way to Harvard) when Dylan came to stay for a stretch. He hero-worshipped Dylan who acted big brotherly toward him.

Bob Dylan: the Man; the Moment; the Italian Meats Sandwich[1]

Chickie Pomerantz was lit.

Opening night of the 1963 Brandeis Folk Festival had been lame. All those green bookbags and black turtlenecks. All those skanks and pears. Then this skinny guy with this scratchy voice came on singing about some farmer starving to death in South Dakota. Chickie and Kevin Cahill and Frannie St. Exupery and a couple other jocks tossed beer cans at the stage.[2] “You shoulda seen the assholes run,” he said, coming back to the dorm.

I went the second night.

A Feminist Dylanist Remembers

It always seemed to me — and I could be wrong but this is my memory — that in the 1960s, boys sat around, stoned or not, like rabbis doing talmudic interpretations of Dylan lyrics. Not girls. My intro to him came in 1966 in 10th grade “AP” (advanced placement) English, where this kind of hidden-bohemian woman teacher (this was a time in my totally and still de jure segregated public HS when the boys where still being kicked out for a day and sent home, if they wore sandals to school with no socks, or if their sideburns got too long, or their hair past their ears, and girls still had to do the spaghetti-strap bend-over test for the old lady assistant principal, to see if their breasts were even slightly visible and if so also remove to home and change). So this bohemian teacher, Ann Sherill, played us The Times They are A’Changing. I remember it was a hot day and the big fan was on, and we girls were stuck on the backs of our thighs (we had to wear dresses then) to our desk seats. I remember being absolutely electrified, probably not just by the title song but also by Hattie Carroll.

The museum as important as the Parthenon (What you lose when you break up a collection)

Another visit by another Greek premier to London, another bout of speculation about the future of the Parthenon marbles, another poll showing that the British people are happy to see them shipped off to Athens, another slew of liberal commentators expressing with characteristic superficiality the view that the marbles “belong” in Greece, another failure by almost everyone to ask what might be lost if that were to happen.

Not that it constitutes much of an argument, but in fact the level of public support for the restitution of the marbles seems to have dropped by over 20% in the last decade, from 77% to 53%. It may be that this has something to do with the issue becoming yet another front in the culture wars, with Reform and its media boosters coupling the metopes in the British Museum with the fate of the Chagos islands. One result is a double irony in which the Right wants to charge people to see the marbles and the Left advocates free entry not to see them.

Whither Disillusion: I Wanna Watch College Ball (“to be sung to the tune of “I Wanna Be Bobby’s Girl”)

I. Dislocation

Too Jewish for Christmas, not Jewish enough for Chanukah: I long ago began cultivating the practice of obsessively watching the NBA cavort on December 25, on which date both sectarian holidays occurred simultaneously this year.

An icy night of snow and blues

It was bitterly cold on a late December night, and snow was starting to blow when I went out to listen to Slim Harpo at Steve Paul’s Scene, a club on West 46th Street and 8th Avenue in New York City that was one of the hippest rock and roll joints the city has ever seen. Hendrix played there in ’67, it was the first place the Doors ever played in New York, and it was a home-away-from-home for touring British acts like Traffic and Jeff Beck. Most of all, it was the premier blues venue in the city.

On this night, with the wind howling and the temperature hovering somewhere in single digits and Slim Harpo playing, I went early. He was supposed to go on at 10:00, and me, I’m thinking it’s fucking Slim Harpo and the place is going to be packed, so I arrived around 8:00. Steve sat me down right in front of the stage at this little table about the size of a dinner plate. There was a one-drink minimum, and I figured I could afford one beer. That was it. I was determined to nurse it through the entire show.

Well, I waited and waited, and I was nursing my beer and checking the door for the crowds I thought would show up any minute, but nobody did. Around 9:30, Steve opened the door and stepped outside, checking up and down the street. Snow was blowing through the open door, and finally Steve came back inside and sat down across from me at the table and introduced himself. Other than the bartender and a couple of waitresses, we were the only two people in the place.

“I guess the blizzard kept everyone at home,” Steve said. “You’re my only customer. I’m sorry, but I don’t think we’re going to have a show tonight. Let me get you another beer. I’m going to go and talk to Slim.”

He came back about five minutes later, followed by Slim and a guy who played a snare drum and a guy who played an old Fender Telecaster. Steve sat down next to me and said, “Slim told me if there’s a paying customer out there, we’re putting on a show.”

Did they ever! They played all of his hits, like “I’m a King Bee,” “Baby Scratch My Back,” “Rainin’ in My Heart,” and “I Got Love If You Want it,” plus covering half the blues canon of the time. All three of them were sitting on stools. They were in their 40s, but to me they looked like Moses coming down from the Mount. Slim wasn’t well, health-wise — he would die two years later — but he wailed on that harmonica and barked out his songs, and between songs, they chatted with Steve and me from the bandstand, which was about a foot high and two feet away. An hour or so later they were still playing when Steve said, “Let’s call it a night.”

We stood there talking while Slim and his guys packed up their instruments — no roadies needed for one electric guitar case, the smallest Fender amp you ever saw, and one snare drum case and a stand. Slim stuck his harmonicas in his pockets and we all headed out the door. Outside, more than a foot of snow had fallen. Steve said good night and tromped off into the blowing snow. Slim turned to me and asked, “You got any plans?” I said no. “Why don’t you come on along with us?” Why not?

Brotherhood

Early afternoon that Christmas, I went up to the Enlisted Men’s Club. It was already pretty crowded with the troops who hadn’t been rounded up to make an audience for the Bob Hope show down at the main post.

There was a spot at the bar, though, and I sat down next to Smitty, the black dude who was the clerk at one of the rifle companies. Smitty basically ran that company; he was a master fixer who knew everything there was to know about the workings of Camp Hovey, which was about 30 miles from the DMZ that divided North and South Korea.

We drank slow beers and bullshitted. I played a lot of cards with Smitty and the Hawaiian guys in his company and we were pretty tight.

“What are you going to do the rest of the day?” Smitty said.

“I don’t know. Why?”

“Come on out to the Texas Club with me,” he said. “We’re going to have a real Christmas dinner out there – not that jive shit in the mess hall.”

“Jeez, will that be all right?”

“You’re with me,” was all he said.

There were six clubs in the village on the other side of the battle group gate. And then, way off about a mile over the rice paddies, all by itself, was the Texas Club. An old mama-san everybody called Agnes ran it; by use over time it had become exclusively for black guys and everybody in the battle group knew it. Smitty was the ex officio mayor of the Texas Club, and he had used his endless connections to extravagantly furnish it. It was a small legend. The MPs never went out there.

Deliver Us From Evil: Legal Opiates in Post-prohibition America

“Is this just getting older?” The crying jags had become more frequent. Color drained from my life and usual distractions. Color drained from my face and skin. The days were interchangeable, tense, and brief. Hurry hurry til you crawl back home half-dead. But there was no cocoon of safety or “me”-ness to return to anymore. I watched the minutes domino mindlessly with no sensation more concrete than dread.

It wasn’t the getting older. And it wasn’t any of the problems (probably projections) I had with my loved ones. A light inside me had turned off. Motions were gone through but nobody was home. Maybe my struggle was part of something bigger, but mostly in a “class-action” lawsuit kinda way. I don’t think it was just the delusions and deficiencies coming home to roost in middle age. Or, it was probably all of that stuff too. But it was also the kratom.

I picked up a bag after reading it mentioned half-positively online.

Staying Alive

art is a track around which one pursues one’s best self.

The author in the process of awakening the morning after speaking with Eileen Ramos.

In September, a friend, the artist/electrician/musician Fran Holland showed me a work by Ramos, a Filipina-American from Piscataway, New Jersey, which he had purchased at the just-concluded San Francisco Zine Fest. After he did, I ordered an assortment of ten ($50, including postage) from her web site [https://eileenramos.com]. They arrived in a 6″ X 9.25″ bubble mailer. On both sides, black magic marker instructed the USPO not to bend.

On Thanksgiving, I Miss My Family (I had a dream of being the only person in America receiving both Social Security and Chanukah gelt.)

My grandmother, Gussie Belinsky Wadler, and my uncle, Artie, in 1950 in the Catskills.

I grew up in the Catskills, in a fading resort town called Fleischmans, where the population in the 1950s exploded in summer with refugees from Hitler.

There was, in fact, a story I came across on a Facebook group, that two sisters, who had assumed the other to have died in the concentration camps, discovered each other at the movies in Fleischmanns.

“Then everybody around them hollered, ‘Sit down!’ Herb says when I tell him about it.

Herb is not a sentimental guy, especially around families.

Plums

Timothy Edmond was a year older than me, but during our childhood, it seemed that he was ten years wiser than me. For just about every milestone of my childhood, Timmy was there. We were the kickball and dodgeball champions of our street. Couldn’t nobody mess with us during a game of Red Rover. Moreover, he was a wiz at Hide-N-Go-Seek. And, he was the all-time champion of Tag or Not It, which was the last game we played right after the streetlights came on and it was time to go inside. As we got older, Timmy helped me to overcome my fear of heights to learn how to climb a tree. I had to learn because Timmy said the best plums were at the top of the tree, and Timmy would know.

I Write What I Like: Thinking About “What Nails It” and a Few Nice Things

“A Mile from the Bus Stop,” 1955, By Jess Collins

Why start a piece on Greil Marcus’s What Nails It with Jess’s painting of Pauline Kael and her daughter in a Berkeley park?

Not only because I want its greens. Marcus devotes the second of the three chapters in his short new book to Kael who taught him what criticism could be. His felt tribute to his friend (and fellow Californian) lies at the heart of his book.

Marcus hasn’t been a confessional writer in the past, but What Nails It goes inward, probing what’s behind his drive to surprise himself with his own words. Composed fast—after seasons when he couldn’t walk up a flight of stairs and nearly a year of silence due to personal health crises—Marcus’s comeback is freewheelin’ fun.

Democracy and Feelings: Yoko Tawada brings Paul Celan into the Age of Fiber Optics

Review of Yoko Tawada, Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel, translated by Susan Bernofsky (New York: New Directions, 2024).

In retrospect, “bowling alone” ain’t even the worst of it.[1] At least then one retains a modicum of public interaction, an immunity-community[2] formed through the public choreography of shared shoes, balls, lanes. The AppStore at this moment boasts several games flouting “Bowling” and “3D” in their title, a rather perverse inversion of the textures of reality and its flattening by the culture of the screen. The increasing digitization of our live has ravaged social capital and concentrated private capital at a scale far exceeding what even Robert Putnam had in mind. We are becoming increasingly aware of just how devastatingly effective the pandemic of social loneliness—precipitated to hitherto unknown extremes by the COVID-era lockdowns—is for fostering political polarization and right-wing extremism.[3] During the COVID-era, our societies insisted that we remain isolated from one virus, even if that meant exposing us to the ills of whatever goes viral. Four years later, we’re still paying the price for pandemic populism.

In March 2021, I learned the lesson the hard way. It was the centenary of Paul Celan’s birth, and Pierre Joris—gifted poet and translator—was set to speak on his recently completed masterwork, a weighty two-volume translation of Celan’s collected poetry, replete with commentary. Being the dark days of the yet unrelenting pandemic, the talk was naturally on Zoom. Celan’s face loomed on the shared Powerpoint as I introduced Joris. No sooner had he thanked the organizers than it began: the n-word scrawled across the screen; a shrill cartoonish scream invading the speakers; rancid GIFS with gobs of semen extruded on co-eds’ expectant faces; and then, there it was: line by line, the swastika drawn in red ink over Celan’s face. It was thus that I—along with Joris, the other discussants, and the 50 some-odd people present for the talk—were made privy to the phenomenon known as Zoombombing.

Girls Lunch

An excerpt from the novel When I’m With You It’s Paradise…

…Leila was run down. After her trip east, as summer gave way to fall, she got sick again. And then, for a whole month, she didn’t get better, or she didn’t want to get better, which amounted to the same thing. She didn’t see friends, didn’t write, stopped going on walks. She spent the days, and the evenings, in bed. She saw a few clients, dizzy and ill in San Francisco hotel rooms. She looked at porn, edged for hours on end to fucked-up fantasies. She felt dysphoric (got off on her dysphoria), started looking at the blackpilled trans subreddits, felt herself getting uglier, or plateauing in her beauty, which amounted to the same thing. She made a lot of money from men by telling them to kill themselves, then she sent some of that to an online Domme in Canada, whose beauty and sexual power, whose body, whose pussy, hurt her in some supremely pleasurable way. Well past midnight, she took baths, and before bed she listened to the new Sally Rooney novel on audiobook (numbed with pleasure but dimly aware that all this bourgeois heterosexual drama, the drama of so-called human life in the twenty-first century, had nothing to do with her), with rain sounds on in the background, cups of rose tea she barely touched on her bedside table.

“Vey iz mir, I Am in a Commercial for Trump, Talking Like Mine Grandmother.”

The Republican Jewish Coalition’s commercial is really bad for the Jews.

Three Jewish women discussing their decision to support Trump and their inability to find decent depilatories under the current administration.

When Is Anti-Zionism Bigotry?

October 7 approaches. Many Israelis will be lighting memorial candles on the anniversary of Hamas’s attack on Israel. The occasion will also be marked by anti-Zionist demonstrations all across the West. It’s been a year of rockets and drones, rhizomic tunnels, assaults on Palestinians in the West Bank, slaughter in Gaza and now Lebanon. A zeeser jahr—happy Jewish new year? I think not.

RIP The Voice and the Vibe (James Earl Jones & Frankie Beverly)

Two African Americans who represented the dreams of their community made their transition this week, and I’m taking a moment to celebrate how they embody the apex, diversity, and massive creativity of blackness.

Fast Pitch

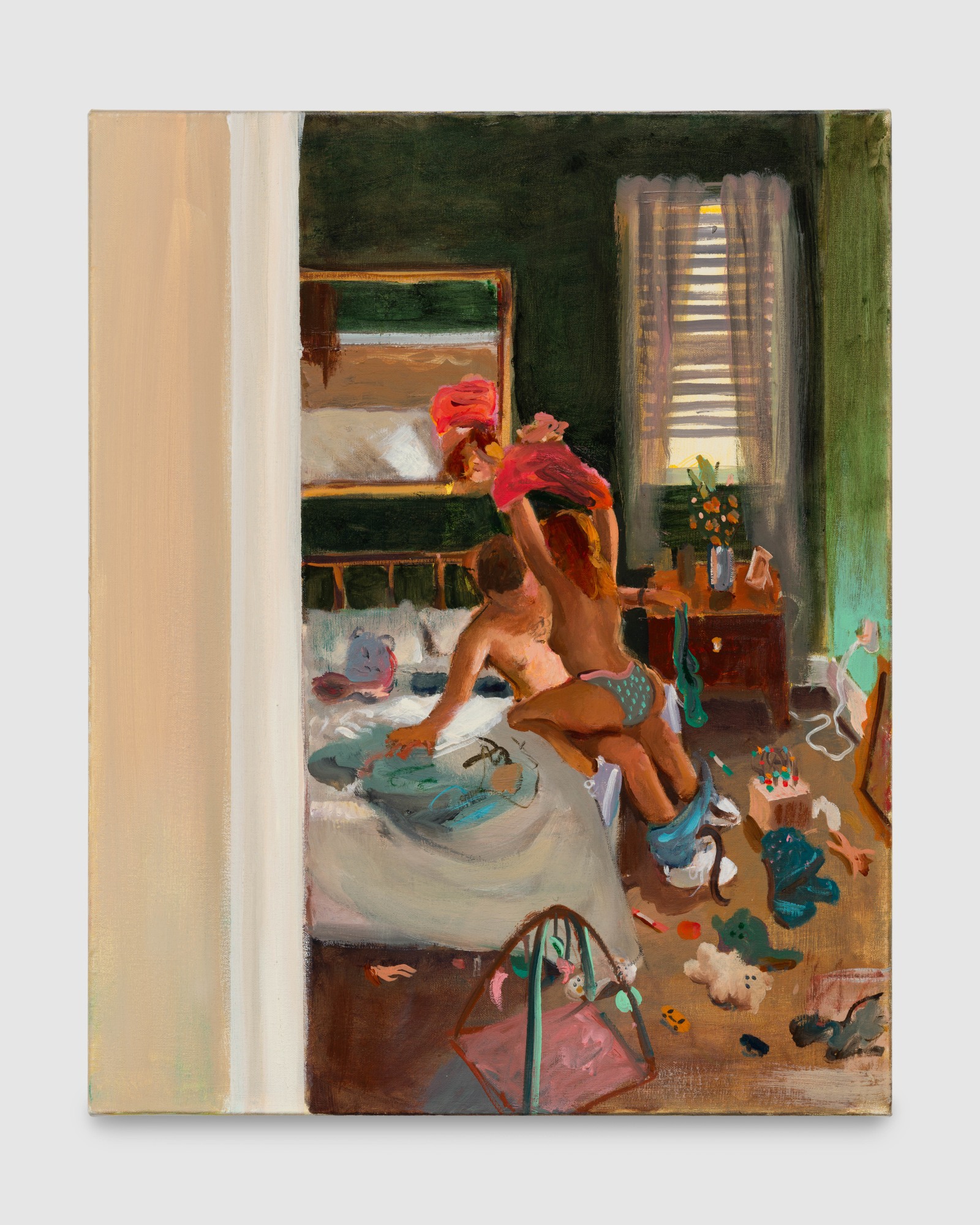

“Reaction Time”, 2024, oil on linen, 20 x 16 inches.

A ballsy one from “Quickies”—Larry Madrigal’s new solo exhibition at Nicodim Gallery in Los Angeles.

Harmon Killebrew

The other night I learned what sui generis meant.

And then: schadenfreude.

I even felt schadenfreude when the Republicans couldn’t elect a speaker.

I looked into Marjorie Taylor Greene’s eyes: cold, vacant, hateful, ignorant.

Then I traded her for an outfielder who could also pitch.

……a throwback.