Adapted from the 17th annual Bozeman Lecture at Sarah Lawrence College.

Talking with most British friends in the immediate aftermath of the referendum was a lot like reading coverage of Brexit in the New York Times and the Washington Post ever since, although with time and distance that first incredulity and fury has subsided into more detached scorn and a bit of spite: Brexit was and is depicted not only as a mistake, but as a vicious mistake made from generally very bad motives, of which the most frequently adduced have been racism, nostalgia for empire, perfect economic illiteracy and, at the risk of what may be taken for a pleonasm, xenophobic Right-wing nationalism.

To clarify something that ought not to matter, but may prevent misinterpretation of what follows: had I been British, I’d have unhesitatingly voted Remain, but I think that it is hard to demonstrate that most of the motives of people who voted otherwise were wholly vicious ones. There were excellent reasons to vote Remain, but there were also unpersuasive arguments offered against voting for Brexit, and the repeated rehearsal of those implausible arguments may have weakened the case for the EU by making people suspect a case of falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, which means that a witness who has lied once may be presumed likely to lie again. Despite its Latinity this is a maxim of the English common law, also a pretty common human intuition. Assuming only vicious motives on the one side and only flawless arguments on the other probably also stops us from seeing the EU’s problems with sufficient clarity. To belabor the obvious, this topic is of more than purely historical interest. Any American giving an account of Brexit to fellow citizens is tempted to say something on the order of what a foreigner wrote at the start of an influential account of mid-19th C. Britain: de te fabula narratur; ‘it is of you this fable speaks’. Below, I’ll assess not whether but in which ways this story may describe our own, or echo apparently similar stories in several other political cultures.

First, some minimal background: On June 23rd, 2016 Great Britain held a referendum on whether it should withdraw from the European Union. 51.9% of the British electorate—amounting to a margin of around 1.2 million votes—voted in favor of exiting the EU, an outcome contracted to Brexit—British Exit—over the course of the debate. This was for several reasons a shocking outcome, and until almost the last minute it’s not clear how many voters on either side thought that it would happen. People had been able to imagine the possible withdrawal or even expulsion of Greece from the Eurozone—duly dubbed Grexit—as a kind of triage operation, but the prospect of a major state voluntarily exiting the EU itself seemed so improbable that at the very last minute the EU Commission refused almost any but the most trivial concessions.

One can sympathize with the Commission’s misplaced confidence, because by 2016 many people expected the EU to eventually, inevitably and inexorably subsume the sovereignty of its component states. This is a little strange because many member states remain strongly opposed to that expectation—not only the UK, but both Germany and France, and among others Denmark, the Netherlands, Hungary and Poland. EU governments, jealous of various aspects of their sovereignty, have imposed significant limits on the European Parliament, which is usually described as the EU’s directly elected legislature, despite having no right to initiate legislation. As things then stand it was also problematic, because the EU’s executive is elected by neither the EU’s citizens nor by the EuroMPs, so if an unreformed EU does come to possess much greater sovereignty it will exacerbate what is euphemistically known as the EU’s democratic deficit. Still, from its very beginning in 1952, when Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany created what grew into the EU, the European Coal and Steel Community, the EU was expected to become an ever-deeper union.

And a deeper union is what it steadily became: the 1957 Treaty of Rome created the European Economic Community, a free trade area. In 1973 came the first expansion of the EEC with the accession of the UK, Ireland and Denmark, and by the summer of 2016 the EU included another twenty-two European states. The 1990 Schengen Convention abolished internal borders, and now includes twenty-six of the members states. The EC became the EU in 1992, with the Maastricht treaty, and the Lisbon Treaty of 2007 changed the EU’s basic constitutional arrangements, although only after a new EU constitution failed to secure unanimous consent from the electorates of its member states. So while the EU began as a confederal union—a league of sovereign states pooling sovereignty in a smallish number of areas—it has at least on a rhetorical level always aspired to be a federal union, and by the summer of 2016 had in some respects become one: most of the member states have a common currency, all had recently created a foreign minister and the beginnings of a diplomatic service, and there are now a few small elements of an EU army.

The Eurozone has so far had very bad consequences for a number of member states, most cruelly for Greece, the EU foreign ministry has so far proved a disappointment, the first steps toward an EU army are within NATO considered a dangerous waste of very scarce resources, and large anti-EU parties have arisen in a considerable number of the member states, but on the eve of Brexit a true federal union was still widely imagined by Europhiles both inside and outside the European Commission to be Europe’s long-term future, although the details of how the EU would get to that future remained obscure. In the views of its enthusiasts a truly federal EU was desirable practically and above all morally: it was asserted to have kept the peace in Europe since its creation, it was supposed to have created a deeply attractive social market economy as a model superior to what prevailed in either the US or the old Warsaw Pact states, it was thought to have effectively chained the demon of war and the competitive nation states that had made serial use of war, and in a diffuse way its further deepening and broadening was widely imagined to be inevitable, not least because when various national electorates had voted down expanded federal powers the EU had either asked them to vote again, or achieved the next advance by other means. So on June 24th of last year, a lot of people in the UK were both in shock and in many cases enraged. And there was shock in the rest of the EU as well, and if not rage, a vow to make sure that the UK did not do well out of Brexit. In both places, and also within most American circles that take an interest in foreign affairs, there was the usually incredulous question, how could this have happened?

Various exit polls addressed this question, and Lord Ashcroft’s poll, which surveyed more than 12,000 voters, is a well-regarded example. Ashcroft found—I am quoting from or paraphrasing his poll—that the older the voters the more likely they were to have voted to leave the EU. Nearly three quarters of 18 to 24 year-olds voted to remain, falling to under two thirds among 25-34s. A majority of those aged over 45 voted to leave, rising to 60% of those aged 65 or over.

A majority of those working full-time or part-time voted to remain; most of those not working voted to leave. More than half of those retired on a private pension voted to leave, as did two thirds of those retired on a state pension.

Among private renters and people with mortgages, a small majority voted to remain. Around two thirds of the tenants in what Americans call public housing voted to leave.

A majority (57%) of those with a university degree voted to remain. Among those whose formal education ended at secondary school or earlier, a large majority voted to leave.

White voters voted to leave the EU by 53% to 47%. A third of those describing themselves as Asian voted to leave, as did a quarter of black voters.

Professionals and managers were the only social group among whom a majority voted to remain (57%). Nearly two thirds of the group the British demographers denote as C2DE—semi-skilled and unskilled workers, and also people who are entirely dependent on the welfare state, voted to leave the EU.

What did the exit poll say about why people voted as they did? Nearly half of leave voters said the biggest single reason for wanting to leave the EU was “the principle that decisions about the UK should be taken in the UK”. One third said the main reason was that leaving “offered the best chance for the UK to regain control over immigration and its own borders.” Just over one in eight said remaining would mean having no choice “about how the EU expanded its membership or its powers in the years ahead.”

Only one in twenty said their main reason was that “when it comes to trade and the economy, the UK would benefit more from being outside the EU than from being part of it”, whereas a small majority of the electorate thought EU membership would be better for the economy, international investment, and the UK’s influence in the world. I think several things stand out. First, people who voted for Brexit greatly valued what most people would call national sovereignty. Second, the people who voted for Brexit were the voters most dependent on the welfare state, something they did not owe to the EU: they had themselves created it using their own share of parliamentary sovereignty in 1945, and have been largely determined to maintain significant portions of it ever since. While the welfare state has been pared down by successive British governments, its crown jewel, the national health service, remains the most valued and admired institution in the UK. Third, the younger you were, the less you were compelled by arguments about sovereignty. Being better educated also correlated with reduced passion for sovereignty, but since being better educated also meant that you were almost certainly richer and less dependent on the welfare state, one might steal an old joke from Tom Stoppard, and note that while there are some first class arguments against more absolutist conceptions of national sovereignty, you may have to be travelling first class to really appreciate them.

The word sovereignty tends to exasperate people who voted against Brexit, also some people who deride other people’s sovereignty from abroad, to the point that some people who oppose Brexit will only use the word in print with quotation marks around it, as if it didn’t actually exist, with the implication that people who claim to so value sovereignty have either taken a Golden Calf for a god, or else really value something else, something they are unwilling to name. This prophylactic use of quotation marks was used in a recent news story by the New York Times’ London bureau chief, and last summer by a justly-esteemed British novelist, Zadie Smith, when writing in the NYRB. In a book centered on a passionate plea for the conversion of the EU into a true federal union, a horrified Europhile and Eurocrat, the former Belgian Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt, put those incredulous quotation marks around the word ‘independence’, apparently something only the deluded prefer to the extinction of national soverignty.

A common charge is that by sovereignty or its synonyms Brexit voters were actually expressing a racist hostility to immigrants, and that in the referendum racism carried the day. There is evidence for this, but a lot of it is indirect, ambiguous or inconclusive. For exmple, the July after the Brexit vote saw a 41% increase in what the police of England and Wales considered racially aggravated incidents when compared to police records of such incidents in July of 2015, which is suggestive, but the number of additional incidents was 1582, and even projecting this forward on an annualized basis the number is too small to prove extensive racist motivation in the electorate of a country of sixtyfive million; the ugly disinhibition of a nasty minority does not necessarily explain the votes of a vastly larger majority. Similarly, Nigel Farage, in 2015-2016 the leader of the Europhobic UKIP, made memorable Islamophobic remarks, unveiled a racist poster, on one occasion praised Enoch Powell’s notorious rivers of blood speech, and was publicly deeply unpleasant about Rumanian immigrants. After the Leave camp’s economic arguments about Brexit had been pretty much routed Farage and UKIP became the most visible face of Brexit, and the xenophobic and islamophobic aspects of their campaigning have been adduced to explain why the referendum went UKIP’s way. Did Farage’s racist language attract the votes that carried Brexit? We cannot know, not least because Farage also campaigned against what he depicted as the EU’s vast cruelty toward and deception about Greece, against international finance capital in general and Goldman Sachs in particular, in favor of Putin’s annexation of Crimea and against NATO, and he promised to succor the National Health Service. We cannot know which if any of Farage’s themes moved non-UKIP voters to vote for Brexit; we do know that UKIP voters hold many views that are normally considered Left positions, and if those UKIP sentiments make for an electoral majority, Jeremy Corbyn is in like Flynn…but according to all known polls, he isn’t.

Brexit voters almost certainly disliked increased levels of immigration. Racism is tougher to show because seeking to reduce the non-white share of the British population by withdrawing from the EU would have been a remarkably ineffective tactic, since withdrawal from the EU will diminish only an overwhelmingly white immigration. The EU immigration British voters clearly voted against was from Poland, Rumania and Bulgaria. While Bulgaria has a significant Muslim minority, I doubt that many British voters know this, because I have never seen any reference to the fact in the British press, which is rarely xenophile when running stories about Muslim immigration. More importantly, EU immigration from the new member states made up only 30% of immigration into the UK since 2004, and the 70% of immigration from non-EU areas included almost all of the non-white immigrants. British governments, Tory, Labour and coalition, could have very easily greatly restricted that latter immigration, none chose to so, and non-EU immigration did not feature in the Brexit campaign. It is possible that when explaining Brexit the perceived inability to control immgration—sovereignty—mattered as much as the immigration itself.

Valuing national sovereignty more than greater EU federalism is pretty common in a number of EU member states, particularly ones that have only recently recovered their own sovereignty, e.g. Poland, also in founding states like France, and last week the two strongest anti-EU parties together had 41% of the vote in the first round of the French presidential election, but 41% of an electorate does not win either a referendum or a national election. Why was the UK so different? To pick what may be an outlier on the other side, among strong EU states with majorities strikingly loyal to the EU we can count a very conspicuous Germany. German voters may have grave doubts about certain proposed developments in the EU’s constitutional structure—for example, the possible emergence of what Germans call a “transfer union”, by which they mean one in which Germans fund what they take to be the profligacy of other EU member states. But large majorities of Germans seem much less passionate about the virtues of untrammelled national sovereignty than are at least older and poorer British voters. Why might these people see the issue of ever-deepening EU federalism differently?

I was teaching in Berlin when the Brexit referendum was held, as I’ve done every summer for the last ten years; I got to London only in early July. Britain and Germany are the EU states I know best; I’ve taught in both countries, and spent a fair amount of time in each. I find Germany’s passionate commitment to the European Union not least interesting because the EU is the culmination of a project designed to constrain German power and limit German sovereignty. Britain, while until July perhaps Germany’s closest ally within the EU on the issue of the speed and extent of the Union’s progress toward federalism, is now clearly the EU state least committed to the EU. My hunch—it is no more than that—is that majorities of British subjects and German citizens hope for different futures because they imagine different pasts.

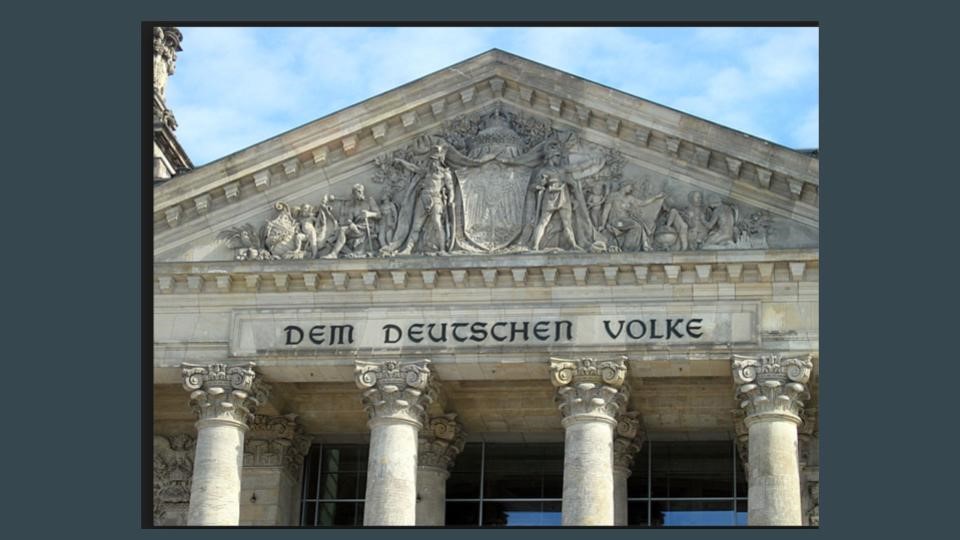

To get a sense of those different imagined pasts, please look at this photograph of the main entrance to the Reichstag, the building planned when the victors in the Franco-Prussian War created the Wilhelmine Reich, at the time of its creation the most powerful and modern state in Europe, and possibly the world—in 1918, it took the combined efforts of almost every other modern state to bring it down.

You will notice that over the main doors it says “Dem Deutschen Volke”.

This is a dative, and means “For the German Volk”. This inscription is not original, and when added in 1916 annoyed the Kaiser, because to Wilhelm II’s ear it sounded like a pledge of democratic governance. The phrase eventually became disturbing for another reason: Dem Deutschen Volke implied something like “For the German Race”. Nationalism is not in my view an intrinsically and elementally racist project, but within twenty years Dem Deutschen Volke was an intrinsically and elementally racist phrase. In 1935, Article 1 of the Nuremberg Laws had distinguished a citizen of the Reich from other subjects of the state, while Article 2 limited citizenship to subjects of German or kindred blood.

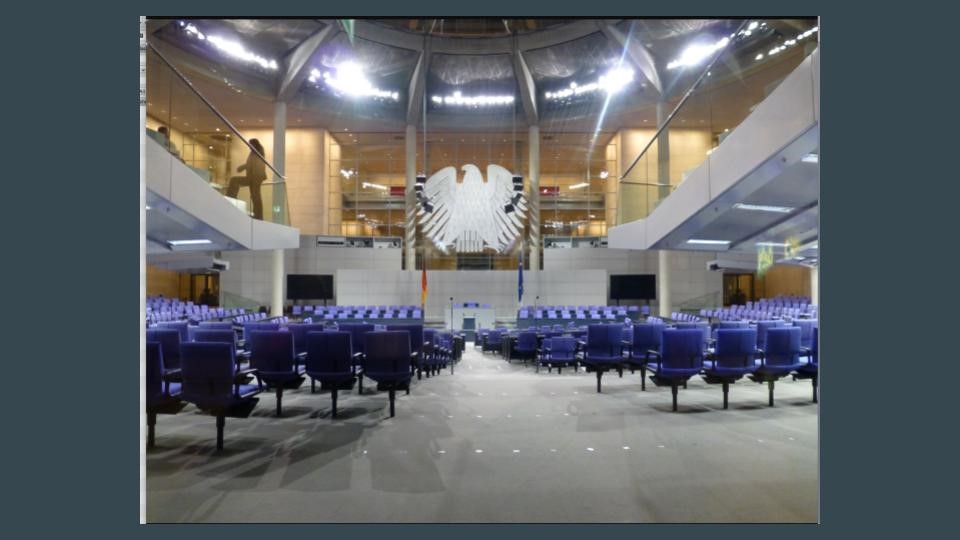

Inside the Reichstag, which is now home to the Bundestag, the German Federal Republic’s legislature, a piece by the conceptual artist Hans Haacke was in 2000 installed by vote of the Bundestag. The art work is titled Der Bevölkerung, a word meaning “Population” and a term used by demographers rather than Volk, the word the Third Reich made odious to many modern ears. Der Bevölkerung, a genitive which suggests “of the German population”, was both intended and understood as an explicit political response to the phrase Dem Deutschen Volke. Although vigorously attacked from the Right, also to a much lesser degree from the Left, the installation is still in place and can be seen from every floor of the Reichstag. Germany still has ius sanguine rather than ius solis laws on citizenship—in most cases one is still a German citizen because of proof of common descent rather than by place of birth—but in the very center of the Reichstag Der Bevölkerung challenges the moral and political limitations of ius sanguine citizenship on a daily basis. What it means to be a German citizen had been contested in awful ways, and is now contested in profoundly admirable ways. Many Germans are for understandable reasons at least suspicious of careless claims about the naturalness and reasonableness of the nation state’s absolute sovereignty, and are not averse to seeing constraints on what nation states can do, because they remember feelingly some horrific things national states have done.

By contrast, the most famous and quotable British thought on the subject of majoritarian identity politics is probably W.S. Gilbert’s:

He is an Englishman!

But in spite of all temptations

To belong to other nations,

He remains an Englishman!

This was of course a joke, and a popular one. Contesting the essence of political membership in the United Kingdom has only rarely been imagined to be a particularly urgent problem. There have been famous and sometimes bloody exceptions—1776, the First Reform Bill and the Easter 1916 are among the exceptions, as are the Troubles and the recent successes of the SNP—and while the matter probably looks very different when seen from Derry or Amritsar, the warning in Haacke’s work of conceptual art, placed in one of the Houses of Parliament, would have little immediate relevance to a majority of British subjects drawn from a couple of key decennial cohorts. I think that last July this became a political fact of some importance.

Most photographs of the restored Reichstag show a remarkable amount of glass. Little of that glass is original; it dates from 1999, and a staggering amount of clear glass is also a feature of the Bundestag’s legislative chamber within the Reichstag.

All that glass means something: it is intended to dramatize the proposition that legitimate political power must not operate in secret, and our ability to always see it operate is a prophylactic measure against the potentially catastrophic abuse of even elected political power.

By contrast, if you look at a standard photograph of the Houses of Parliament in London you will notice that there are no very large panes of glass either inside or outside of the building, and there is certainly very little glass when compared to the Bundestag,

To the best of my knowledge, nobody minds.

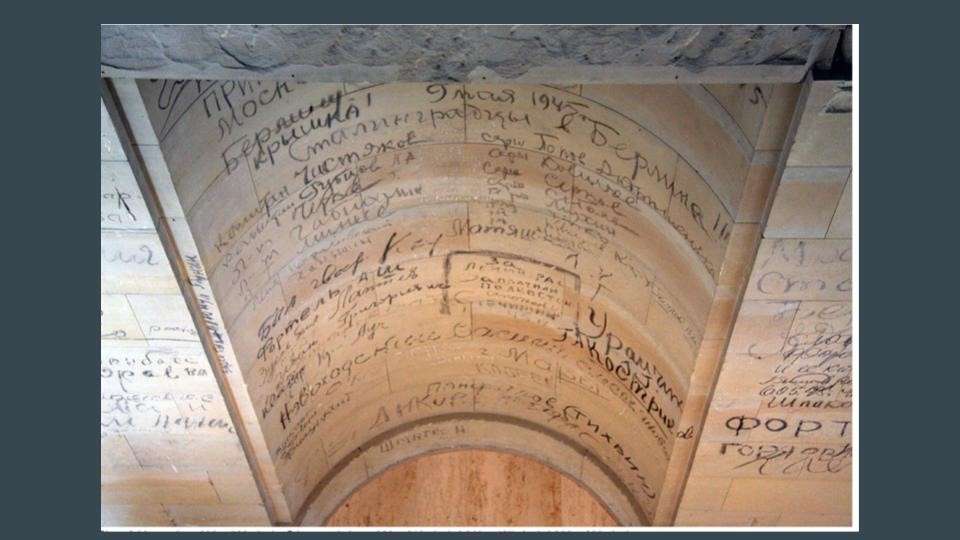

Another thing: if you go into the Houses of Parliament, you’ll see no graffiti. However, there’s a lot of graffiti in the Reichstag. It dates from 1945. This graffiti covers every surviving original wall of the Reichstag. It is in the Cyrillic alphabet, and says things like “I came all the way from Stalingrad” or “Leningrad to Smolensk to Berlin”. The decision to leave it place when the Reichstag was restored and returned to its original purpose was understandably controversial, and not all of the graffiti remains—a certain amount of it apparently said things like “Russian sabres in German scabbards”, although usually in much less metaphorical language. Those graffiti referred to the rapes committed by the Red Army when it conquered Berlin. Low-end scholarly estimates of the number of Red Army rapes in what became East Germany are around two million, and some respectable estimates are now significantly higher. People pointed out that some Germans who would visit the Reichstag after it was restored would be victims of those rapes. Forcing the victims to see those graffiti would be indefensible, so they were removed, as were most of the other obscene graffiti—but not quite all of it; somewhere an almost obscured phrase states “I sodomize Hitler”, although I am told that the demotic Russian uses different words.

Why leave this evidence of defeat and humiliation, also initially of horrific violence, on the walls of the Reichstag? Someone who works in the Reichstag and is paid to explain these things told me that it is because Germans are determined to remember that the Reichstag is not, as that German lawyer and guide explained, in absolutely unironical words, the Mother of Parliaments. He explained that Germans know that they live in a parliamentary democracy because their country lost a war, that they then lost that parliamentary democracy through their own efforts, and only regained democracy because they lost a subsequent war. My impression is that in striking contrast a lot of older British subjects think that they live in a parliamentary democracy because the United Kingdom won those same wars, and that many other people live in parliamentary democracies because Britain won those wars.

Another and nowadays perhaps less obvious point: in 1945, the British electorate seems to have seen the creation of the modern welfare state as the nation’s part payment to the people who had fought and won the great wars of the 20th C, which meant the nation’s payment to itself, and to its posterity. After 1945 the vast majority of Europeans fell out of love with war, the European Coal and Steel Community was intended to make another war between France and Germany impossible, and all of the subsequent evolutions of what became the EU have retained and expanded that goal. Avoiding another European civil war remains chief among the EU’s purposes, and another urgent goal of the EU is to secure and enforce liberal democratic political norms in the EU’s member states. But for comprehensible reasons, Europeans became radically averse to war at different rates—and British and German 20th C. war memorials are now very different.

I know of only one memorial to the First World War in all of Berlin, Käthe Kollwitz’ Pietà, a woman grieving for her dead son.

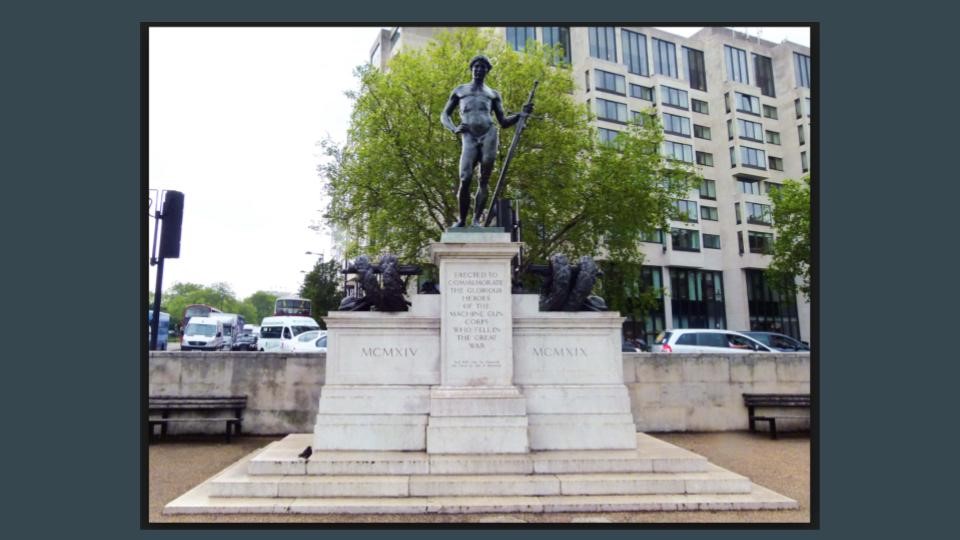

It is interesting to contrast it to a British memorial featuring a slender boy, not an obviously martial sculpture when you first see it but more martial than it first seems, because the young boy is David, the memorial is to the Machine Gun Corps, and the inscription on the plinth reads “Saul has slain his thousands, David his tens of thousands”.

Perhaps this memorial and its remarkable inscription survives as a macabre monument to a vanished sensibility…but perhaps not.

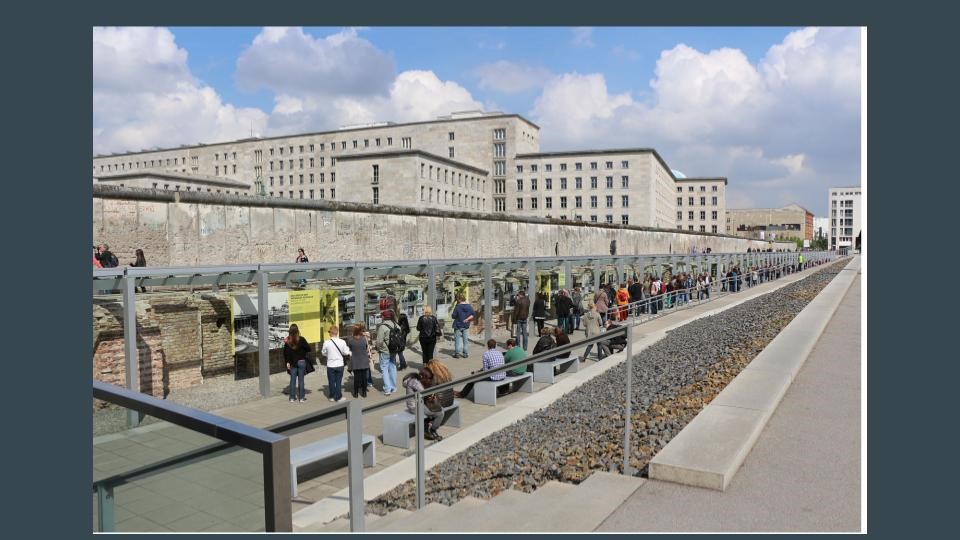

One Berlin memorial to the Second World War is titled The Topography of Terror, and it used to be the Gestapo’s headquarters. When the memorial was first created, in the early 1990s, it was mostly a hole on the ground—the RAF had smashed the building’s roof and all of its above-ground portions, but you could look down and see the basement cells where enemies of the regime were tortured and murdered.

If you descended you could see photographs of some of those victims, with texts explaining what they had done, and what had been done to them. A friend once noted that the view from above almost suggested that the hand of God had torn away what had concealed those crimes from the heavens. But of course it wasn’t the hand of God, it was the hand of Sir Arthur Harris’ Bomber Command–

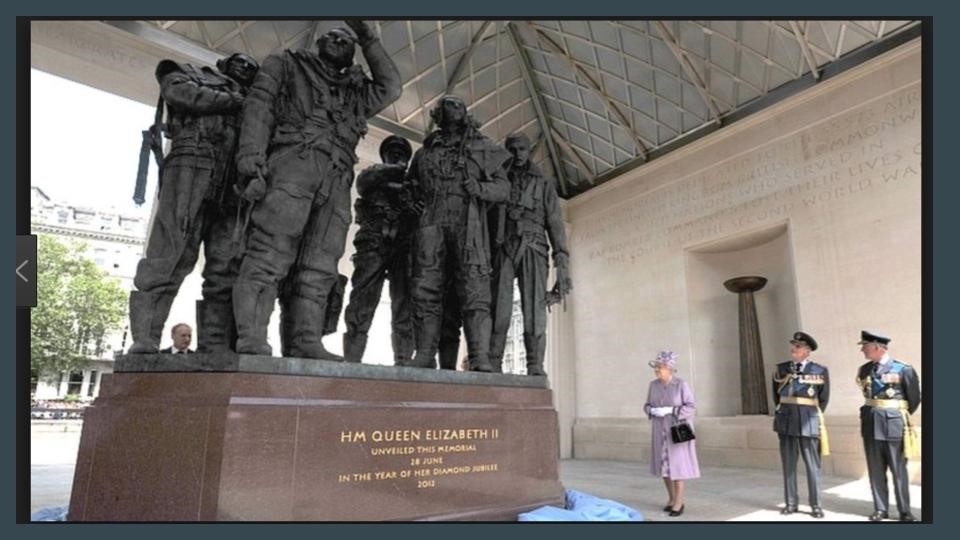

men who at the cost of 60,000 of their own dead had destroyed a fair portion of the 600,000 German civilians killed by Allied strategic bombing. The British put up this memorial in 2012. German and British memories of the last century’s world wars are remarkably and revealingly different.

One last observation about what that German lawyer called The Mother of Parliaments. The Reichstag is by British standards a new building, and it has not been used as a parliament for almost half of the time it has existed. The Houses of Parliament are in the Palace of Westminster, and a structure with that name has existed in that place for a thousand years—what was billed as the Thousand Year Reich, by contrast, lasted eleven. Parliament has been meeting in this vicinity for around nine hundred years. The current Houses of Parliament are in buildings that replaced predecessors destroyed by fires, but not by the equivalents of Reichstag fires. The UK does not retain a working parliament because of a foreign occupation. Other than in one excessively ingenious interpretation of 1688, no foreign army has occupied England, at least, for very close to a thousand years. A terse definition of what is called parliamentary sovereignty would be ‘when the power to make the laws is held by an elected legislature’. What that German lawyer unironically called the Mother of Parliaments has been in the sovereignty business for quite a while, during which time, as I noted above, it has, among other things, created the National Health Service, the thing the British most admire about their society, and also what the British, no matter how preposterously, until very recently thought one of their best inventions, the one they call the rule of law. As noted above, a significant number of older British voters see the EU as an institution that may (via mass immigration) indirectly threaten the British welfare state, something they believe that British voters created while exercising their democratic sovereignty in 1945, at the very moment when the oldest Berliners—I have met some of them—remember other Berliners eating zoo animals amid rubble an extremely popular German government had indirectly created while exercising its sovereignty. For comprehensible reasons, different historical experiences make both people and generations value absolute sovereignty to different degrees. So in my view, older members of the British electorate had fewer and certainly less dramatic reasons than had almost any other Europeans to mistrust popular sovereignty, parliamentary sovereignty, or the nation state, and even if, strictly speaking, the UK isn’t one, it is, to repurpose a sadly dated American phrase, close enough for government work.

What else might the British electorate have hoped for or feared? And more tersely, what might Europeans watching Brexit unfold have hoped for, or dreaded?

Most opponents of the EU were cheered, and there are more of them than you might think if you read a lot of Europhile editorials in which the UK is described as an extreme outlier dreaming of lost empire. In the European Parliamentary elections of 2014 Eurosceptic parties took around a quarter of the seats. Very few of those of those parties make it into American news stories: UKIP in the UK, the National Front in France, maybe the People’s Party in Denmark, certainly SYRIZA in Greece, Sinn Féin in Ireland and the Five Star Movement in Italy. Most don’t, but there is at least one Eurosceptic party in every EU state. They are not all minute factions: In Hungary, Eurosceptic parties won 2/3 of the seats in Hungary’s last national elections, and in Poland the Eurosceptic Law and Justice party, the largest in the country, is in a coalition ruling Poland. The Hungarian and Polish Eurosceptic parties, while authoritarian and in some other ways unattractive, with the exception of Hungary’s Jobbik cannot be accurately described as neo-fascist, and in some countries, Portugal for example, also Greece, Euroscepticism is at least as likely to be a position on the Left as on the Right—which is in some ways true also true in the UK, where Eurocepticism now divides the parties themselves as much as it divides them from one another. I’ve already mentioned the first round of France’s presidential election, where the French Left’s share of a large Eurosceptic vote was not much lower’s than the Right’s. And parties and election results are not always the whole of the story: Spain was one of the very few EU members states to approve by referendum the proposed EU constitution on 2005, but in 2015 a poll found that 61% of the electorate didn’t trust the EU, and only 25% did. In Sweden Eurosceptic parties took around a quarter of the vote in the 2014 European Parliamentary election, and opinion polling suggests that this result understates popular levels of Euroscepticism. Some but not all of these parties were cheered by Brexit. In Poland, for example, Law and Justice want the EU’s very considerable largesse while despising its attempts to impose what are seen as Western Europe’s odious social norms, and Poles also have concerns about the alliance systems that underpin national security, which gives Law and Justice reason to fear the possible collapse of the EU, and makes some in Poland determined to make Brexit as painful as possible, pour encourager les autre.

Some British Europhiles also dreamt of future EU norms producing more highly regulated labor markets, producing a world in which Thatcherite and Blairite neo-liberalism would be reversed. In this vision the EU stood between neo-liberalism and what remained of the welfare state. But as preposterous as the proposition seemed to their opponents, some on Labour’s Left feared and actively opposed the EU as an elite neo-liberal project threatening hard-won social protections. This view was held by one of my old heroes, E.P Thompson, and has apparently been retained by Jeremy Corbyn, who has refused to say how he voted on Brexit. The position has been dubbed Lexit—Left Exit.

As for Brexit dreads, some British Europhobes on the libertarian Right dreaded the EU as a political order that might someday impose over-regulated labor markets, which were feared, and not only on the libertarian Right. The Rightist Europhobes who feared this may have contrariwise dreamt of an ever-less regulated economy that probably would not have worked as advertised, but these Europhobes could point to extremely high youth unemployment rates in many EU states, and to the great harms the Euro and the Bundesbank are often thought to have together inflicted on some Europeans. Some Europhobes on both Left and Right are tempted to explain German Europhilism in economistic terms—in this vision a weak euro created by the immiseration of southern Europe significantly subsidizes German exports. I do not myself think that Germany cunningly wrecked the Greek economy to drive down the price of its manufactures, but Europhobes of various political complexions understand very low and sometimes negative growth rates and very high unemployment as the fruit of both the euro and of policies the EU forced on Ireland and Greece, and may soon force on Spain, and then Italy, and someday France. In conjunction with the crash of 2008 the euro has been at least bad and sometimes worse for many of the younger unemployed, the under-employed and the never-employed. I won’t assess various visions of the EU’s relationship to the various political economies of its states, only note that the EU has been demonized in antithetical ways, is also the repository of antithetical hopes, and that the damage wrought by the euro has been not only a political but a moral disaster for the EU. The euro is unwelcome and almost unacknowledgable evidence that the most striking and symbolically charged advance toward ever-greater union did great damage to what we might call actually existing federalism.

What else did Europhiles hope for? Many of the French long dreamed of the EU as a counterweight to America, so that a French-dominated Europe would be a third superpower in what looked like a bi-polar world. In the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the stagnation of Japan, and just before the extent of China’s rise was widely understood, the EU looked even more like a counter-America. Some enthusiasts in both the EU and the US wrote those books arguing that a larger, richer social market economy in the EU would eclipse an American-style market economy as the most attractive form of polity.

But Europeans hoped and feared much more. There was the nightmare of nation states as the sources of catastrophic continent-wide wars, and the corresponding dream of an EU-forged perpetual peace within Europe. Oddly enough, it was the very mildly Eurosceptical Margaret Thatcher who when quelling a mutinous Eurosceptic Tory flank claimed that the EU had kept the peace in Europe since 1945. During the late phases of the Brexit debates Thatcher’s remark became an urgent Europhile warning. A possible problem with this warning was that it was nonsense, and too many people knew it. From 1945 until the end of the Cold War, NATO and the Warsaw Pact kept the peace in Europe, and when the Soviet Union collapsed and most of the American troops went home, the EU’s first and to date last effort at keeping the peace came with the Yugoslav succession wars, where the EU along with the UN failed miserably and shamefully. The U.S., for this purpose euphemistically termed NATO, brought those horrors to an end, for which it has yet to be forgiven by Europeans like the Greeks, who remain disgusted by the use of American violence to stop Orthodox Christians from murdering, tormenting and expelling first Muslim Bosniaks and then Muslim Kosovars. The reason I think this matters is that older British voters probably have a lively sense that it was not the EU that kept the peace in Europe, but rather, among others, the British Army on the Rhine which for fifty years was charged with keeping the Red Army out of the Western reaches of the North German Plain, while, among a few others, the Royal Welch Fusiliers and the Irish Guards and the King’s Hussars were tasked with keeping the Red Army out of Berlin. I happen to know people who at the last minute changed their intentions and voted for Brexit in response to threats of this very kind, part of what was dubbed by some Europhobes Project Fear. In Lord Ashcroft’s poll, one in four British voters said that they’d decided how they would vote only a week before the referendum. My impression is that plangent memories of successive BAORs—there have been two, one of which one only got its name after fighting from Normandy to beyond the Elbe—are very weak among most British voters under the age of fifty, but significantly stronger among some older ones.

One could also talk about several other Brexit hopes and nightmares, among them the dream of free trade and free movement and the much less grand reality of a Free Trade Area, which is what the EU actually is, the dream of a common European cultural sphere evolving into a European federal state, and the tension of that dream with diversity and multiculturalism, the false dream of a Brexit dividend and several nightmares about Britain’s economic future outside the EU, the dream and the nightmare of administration as an escape from politics, the dream of the welfare state as a universal norm and the nightmare of mass immigration as the gravedigger of the European welfare states, the dream of cosmopolitanism and the nightmare of its perceived risk to the cultural cohesion and social solidarity that may so far have underpinned democratic welfare states.

But this is already a long essay, so only two more points: in what sense can we reasonably say de te fabula narratur—that this story is about us? I think that the risks of ignoring the very unevenly distributed costs and benefits of both liberal and social democratic political economies is pretty clearly a story about us. What is going on in Poland and Hungary—the renewal of illiberal and possibly vicious majoritarianism—is sometimes taken to be a story about us, and about Brexit, but since I do not think illiberal and possibly vicious majoritarianism is too obviously what happened in Brexit, Brexit is not in that sense a story about us. A political reaction to globalization by possibly nostalgic but above all significantly older fellow citizens is a story about us—but it is not a story about France, where the National Front has the support of 40% of younger voters. It is a story about the sheer number of Europes we still have to remember and distinguish from one another, and why a truly federal European Union is so much more difficult a project than we had suspected before the 23rd of June.

And one last thought: I began with a joke about how some people might take the phrase “xenophobic Right-wing nationalism” as a pleonasm, meaning that all nationalisms are an ungenerous and very dangerous business. This view of nationalism is at the heart of the EU project, and since that project may now be at risk I would like to suggest that this view, which excludes the possibility of liberal nationalism, is in historical terms at least a novelty, and might sometimes be a mistake. So I’ll end by quoting from an optimistic vision of liberal nationalism expressed in a play which also contains visions of uglier nationalism, a play put on in London a few months after Brexit and by most reports admired by the Donmar Warehouse’s subscribers, a group of British citizens almost fantastically unlikely to have voted for Brexit. The play, which is by an Irishman, at one moment depicts nationalism as the essence of anti-imperialism, and suggests that the wars nationalism made possible were sometimes wars undertaken with good motives and better results. The playwright is Shaw, the play St. Joan, and a few of its lines run as follows:

“They are only men. God made them just like us; but He gave them their own country and their own language; and it is not His will that they should come into our country…We are all subject to the King of Heaven; and He gave us our countries and our languages, and meant us to keep to them.”

This vision may not be true, but I do not think it intrinsically ungenerous.