Peter McKenzie’s parents welcomed Bob Dylan into their life and New York City apartment where he slept on the couch for a couple seasons in 1961. Mac and Eve McKenzie helped introduce Dylan to Greenwich Village’s politics of culture. Peter was in high school (on his way to Harvard) when Dylan came to stay for a stretch. He hero-worshipped Dylan who acted big brotherly toward him.

(Decades down the line, Dylan even offered advice on dating games, though both quickly realized it was inapt.

“Pete, I’m going to give you some very valuable input…I’m going to show you how you can get anyone you want. It’s foolproof. When you got to a party, dress a little off the beaten track but spiffy. Stand against one of the walls as if you’re just observing. It will give off this mysterious aura. Before you know all the women will be coming over to because they can’t resist mystery. Then make your move.”

“Thank you, Bob.” I replied, “Very nice of you to share your knowledge with me. There’s only one problem.”

“What’s that?” He asked, deadpan, already anticipating my answer.

“You’re Bob Dylan and I’m not.”

His laughter on the other end of the phone was immediate. Some things never change in a relationship.)

McKenzie’s account of his familial time with Dylan, Bob Dylan: On A Couch & Fifty Cents A Day, evokes the Village in the early Sixties. On this score it complements chapters in Dylan’s Chronicles and Suze Rotolo’s A Freewheelin’ Time. It’s also in tune with a more scholarly work of Dylanology — Daniel Wolff’s Grown Up Anger: The Connected Mysteries of Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, and the Calumet Massacre of 1913. Wolff’s book links Dylan’s early story and creative development up through “Like A Rolling Stone” with the felt history of working class struggle during the American century. McKenzie’s father, Mac, carried that history forward. He was a teacherly type without being overly prescriptive.

What follows are excerpts from On a Couch & Fifty Cents a Day that focus on Mac McKenzie’s way in the world and Dylan’s responsiveness to lessons — spoken and unspoken — of this father figure. (FYI, there’s plenty more in On a Couch about young Bob’s pals and sweethearts, guitars and harmonicas, songwriting and performing.)

February 16, 1961 – The First Time

My parents were out for the evening. Although I was half asleep when the phone rang at 11 p.m. I jumped out of bed and sprinted through the apartment to answer it. It was my mother.

“You have to come down here right now. It’s a place called Gerde’s Folk City. It’s on the comer of 4th St., a couple blocks east of Washington Square Park. You can’t miss it.”

“How was Jack’s concert?” I asked.

My parents had attended a Jack Elliott concert at Carnegie Hall earlier that evening.

“The concert was fine,” she replied. “But you have to come down here now! Jack is here with us and one of your father’s oldest friends, Cisco Houston, is performing.”

I knew who Cisco Houston was. Jack and my dad had told me about him. I’d heard some of his records. He was an old Woody Guthrie ·traveling companion, like Jack. A big union man with a commanding presence. The name Gerde’s Folk City was not familiar to me. I heard glasses clanking and people’s voices in the background.

“Jack and your father want to see you,” she added.

Something special must be going on for her to be that insistent, so I grabbed the first shirt I could find, put on my khakis, shoes, school jacket, and out the door I went. Got to the subway stop on the comer of 28th Street and Broadway. As I went through the turnstile, the downtown train was pulling into the station. Five minutes later I exited the 8th Street and Broadway stop. It was a bit chilly, but it didn’t bother me. A few blocks later, there it was, a big awning with the words “Gerde’s Folk City.”

As I started through the door, I suddenly realized it was a bar. I was 15 and walking into a place where, if you’re under 18, you get stopped at the door, turned around, and ushered right back out on the street. And yes, the minute the front door closed behind me, the bouncer was right there.

“You’re a bit young to be here, laddie, don’t you think?”

Before I could answer, I noticed a sign that called for a two-drink minimum. I was screwed. Then a voice from somewhere far inside called out:

“He’s with me. Let him in!” It was Jack Elliott.

“No problem, Jack. Go right in,” the bouncer said.

I’d never been in a place like this before. It was dark, but nicely laid out. The bar at the back was quite long and lined with stools. There was a roomy aisle to walk back and forth with a 4-foot wooden barrier separating it from the main room. The main room had a whole bunch of tables and chairs. Against its far wall, in the center, was a small, raised stage with a microphone stand. A direct spotlight illuminated it. Off to the side was an old, upright piano. I went over to Jack and shook hands.

“Your folks told me why you couldn’t make it. It’s okay. School should always come first. I came down right after the concert to see Cisco sing. He’s a real old friend. See over there? He’s with your dad. They haven’t seen each other since World War 2.”

My father and Cisco were at the very far end of the bar. I walked over.

“Hi, dad.”

“Pete, I’d like you to meet an old friend of mine from the National Maritime Union, Cisco Houston.

“Pleased to meet you, young sir,” said Cisco, extending his hand. He was strikingly handsome.

“Me, too,” I replied. “I’ve heard a lot about you.” He looked at my father.

“Nice kid you got there, Mac.”

I knew my dad’s facial expressions pretty well. They could be very subtle. He had the ability, when needed, to maintain a poker face. When he chose to, it was almost impossible to read. When he was young, he’d played cards for a living. As he talked to Cisco I noticed the sadness in my father’s eyes. It was only later he told me Cisco was suffering from terminal cancer and had only a short time left. Cisco was a courageous man. He’d survived being torpedoed a couple of times in the War. That courage never left him. You can tell a lot about a man by the way he faces death when it stares him in the eye. I’m sorry we never got a chance to see him again. His music had a big effect on Bob.

“Pete, your mother is in the main room with some people. Why don’t you go over there so she’ll know you got here okay,” my father said.

It was clear he had some personal things to discuss with Cisco, so I said goodbye, waved to Jae and went to find my mother. She was sitting at a table right inside the divider, far from the stage. I went over to her and sat down. Two other people were there with her. My mother introduced us.

“Peter, I’d like you to meet an old friend of mine, Marjorie Guthrie, and her son, Arlo.”

I looked at Arlo. He was a year younger than I and had curly hair like mine.

Marjorie was Woody Guthrie’s ex-wife. She lived way out of Manhattan in Howard Beach. Both my mom and Marjorie had been dancers with Martha Graham. Both were wives of prominent figures in the American labor movement. I wanted to talk to Arlo, but since the talk between Marjorie and my mother was nonstop, I kept sipping my soda. Then, when it looked like there would be a break in the conversation and I could talk to Arlo, an all-encompassing cloud of cigarette smoke wafted across the table. The smell was extremely pungent. Sandwiches had just arrived at the table. For me, trying to eat something with that smell hovering over the food was impossible. I thought it would pass. However, no sooner had the smoke cleared and I was about to grab a sandwich when another large cloud came floating by.

Now I was pissed. I had gotten to meet Cisco Houston and Woody Guthrie’s wife. I was hearing stories about Woody and Cisco and learning things about my father from Marjorie and my mother. I was looking forward to making friends with Arlo. In 1956 Pete Seeger had been my elementary school’s visiting music class instructor when I was ten years old in 5th grade there. Everyone was given sheets of paper with the words and music printed on them, and we would have wonderful sing-alongs. Knowing the bond between Pete and Woody I figured Arlo might have some cool stories.

Then that cloud of smoke drifted in, AGAIN. I turned around in my seat to see where that heavy, hanging smell was coming from, and there was the offender. He must have just slipped in and sat down in front while no one was looking. He hardly looked older than me. He was by himself, kind of slouched down, a cap pulled over his forehead, a too big black overcoat, boots, legs crossed, with the crossed leg bobbing like it wanted to go somewhere but couldn’t decide which way to go. Out of the comer of my eye I watched as he put out one cigarette and lit another and realized it wasn’t going to stop. I wouldn’t be able to enjoy my sandwich. I was about to say: ”Would you mind, that smoke is really bothering me. Could you stop, or else move,” when I heard Marjorie Guthrie’s voice.

“Peter, I see you’ve noticed our friend. His name is Bob Dylan. He’s a young folk singer from New Mexico who just came into New York to visit Woody in the hospital. He even wrote a special song for him. Woody liked it.”

That was it. There was nothing I could do now except force a smile and say, “Nice to meet you.”

He looked at me and nodded his head slightly, but made no sound. My mother looked at him from across our table. I had been introduced, so it was only proper etiquette she be polite as well.

“Hello,” she said.

He nodded again, still without a word. My mother turned back to Marjorie and commented: “He has such a baby face and he’s all alone.”

She turned again to look at him in the dim light and saw he was nursing a drink with no food in front of him.

“Have you eaten? You should always have something in your stomach when you drink. The sandwiches on our table came free with the drinks. You have some.”

He looked back at her and muttered something. Even though I was closest, it was unintelligible. My mother lifted the full plate of sandwiches, handed it to me and said, “Peter, give this to him.”

He nodded once again. After I passed it over I couldn’t believe it; I never saw an entire plate of sandwiches disappear so fast — including the one I was going to eat.

Mom and Marjorie resumed talking about old times. It was getting late. Cisco was looking a bit tired, although still engaged in conversation with my father. Marjorie and Arlo had a long trip home. Jack had a few drinks under his belt. It was time to go. I was glad Jack’s concert went well. We all said our goodbyes. My parents and I made it out through the swinging doors to the street. I could now feel how much colder it had become. Fortunately, as deserted as the streets in that part of the Village normally were at that time of night, we got lucky and caught a taxi. At that moment God was definitely on our side.

After Gerde’s

After the night of February 16 at Gerde’s, I figured things would revert to normal. But almost every day, I would come home from school to a half empty bottle of Scotch on the kitchen table and Kevin Krown [a running buddy of Bob’s] engaged in a conversation with my mother. Not our Scotch. We couldn’t afford it. Kevin brought it and drank it while he was waiting for my father to get home. Amazingly, he never seemed inebriated.

One of the reasons Kevin, Jack, and later, Bob, gravitated to our apartment was because of my father’s background.

He had been one of the founders and leaders of the National Maritime Union, NMU for short. All the seamen who worked on regular ships, ocean liners, and the Merchant Marine became members. As First Vice President my father was chief negotiator for all union contracts. The NMU was the first integrated union where its black and white members slept in the same quarters during the 1930s and 1940s. During World War II my father was on the National War Labor Board under Eleanor Roosevelt. They were in charge of providing and overseeing the sailors who worked the Lend-Lease program with England, sending goods on “liberty ships” and other freighters and tankers in a grand effort to help stop the Nazis. Two of the members of the NMU were Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston. Woody’s famous song, “The Sinking of the Reuben James,” is about the first American warship, a destroyer escorting a convoy to England, sunk by a Nazi U-Boat….

Woody also wrote a song about the “liberty ships” themselves called “Talking Merchant Marine.”

Ship loaded down with TNT All out across the rollin’ sea;

Stood on the deck, watched the fishes swim,

I’se a-prayin’ them fish wasn’t made out of tin

Sharks, porpoises, jellybeans, rainbow trouts, mudcats, jugars, all over that water.

Win some freedom, liberty, stuff like that.

This convoy’s the biggest I ever did see,

Stretches all the way out across the sea;

And the ships blow the whistles and a-rang her bells,

Gonna blow them fascists all to hell!

I’m just one of the merchant crew,

I belong to the union called the N. M. U.

I’m a union man from head to toe,

I’m U.S.A. and C.I.O.

Fightin’ out here on the waters to win some freedom on the land.

Woody and Cisco would perform songs together at rallies, strikes, and other NMU functions. Pete Seeger would be there as well, with his banjo and members of the Almanac Singers. Jack had been doing “Talking Merchant Marine” for years. Bob also performed it at his first solo concert at Carnegie Chapter Hall in November 1961…

One of the names that came up was Paul Robeson. My dad had known him. Mr. Robeson was a giant — his intellectual prowess, political activism, outspoken views, and artistic talent made him the Frederick Douglass of his day. He was also an extraordinary athlete. In the original 1936 Broadway production of Showboat, Mr. Robeson with his deep, resonant, baritone voice, made “Old Man River” a national sensation. Later on, Bob got a very detailed history about Paul Robeson from my father. It served as a guide how to walk that very fine line between the personal, political, and artistic. He learned how to expose some part of himself without getting sidetracked by irrelevant gossip while reaching the biggest possible audience. Robeson’s life also served as a roadmap of what not to do…

April 21, 1961

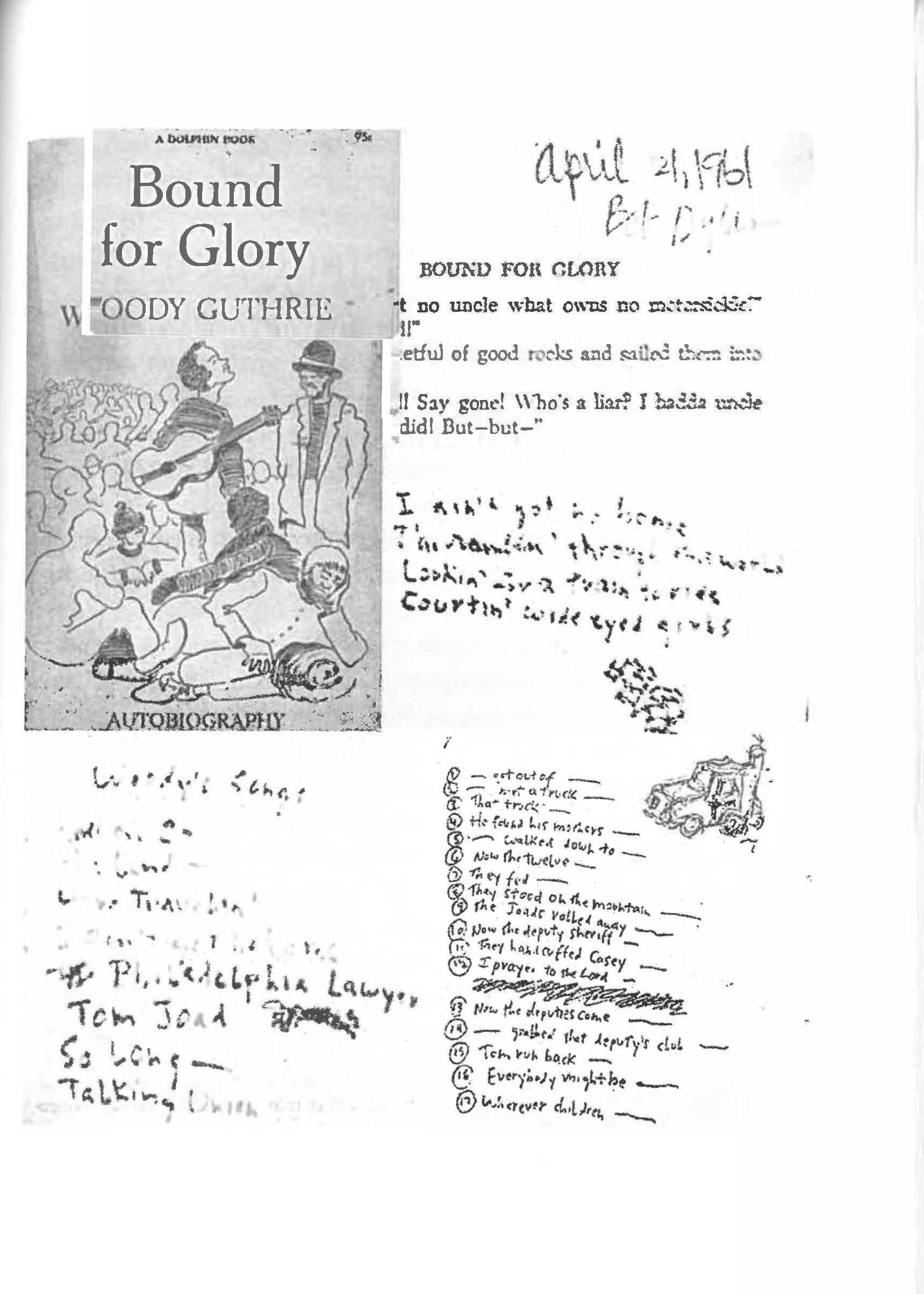

Ten days into his first paying engagement at Gerde’s Folk City, about 7 pm, Bob bounced up the stairs to our apartment. In his hand was his prized copy of Woody Guthrie’s Bound for Glory that he carried with him everywhere he went.

“Have you read it, Eve?” he said to my mother. “You have to read it. It’s a real revelation about life.”

He had already talked to my father about Woody’s union days and listened to all Woody’s records: He knew most of Woody’s songs. My mother thought his enthusiasm was wonderful. She was always happy when a young person showed such passion. She had lived through the Great Depression that Woody wrote about. My father’s actual experiences, though, were a bit closer to what Woody described.

I could see Bob was really kicking up a fuss about the book.

“You have to read it, Eve,” he repeated.

But, there was something else at work. The hype about the book had more to do with me than my mother. Being so good at sizing things up he knew my parents, for their own reasons, had always tried to shield me from their personal experiences in those years the McCarthy witch hunts, the union busting, the pain they went through due to their moral and political beliefs. In the 1940’s my mother used to stand at the apartment door holding a baseball bat when my father came up the stairs at night in case anyone was following, or laying in wait to attack him. Since I was a kid, I had known that goons — hired by people who wanted to weaken and destroy the National Maritime Union — tried to murder him at least twice. Snippets of facts and stories had come up piecemeal over the years, but my parents had never laid out the whole thing. I will never forget the look on Bob’s face when they told him some of the stories. His eyes got wide, and his body shifted forward. He said nothing; he was doing his best to absorb the information.

Bob felt I should know my whole legacy, but he knew he couldn’t interfere. Even though he already had an adoring, captive audience in.me, he was too smart to sabotage my folks’ authority directly. His agenda was different. He kept going on and on about the book, knowing my mother would never read it. Still, he insisted, “If you get the chance, Eve. Just in case. I want you to have it.”

When Bob decided to be persistent it was impossible to say “No.” He took that well-read copy of Bound for Glory, opened it to the inside front cover, dated it, signed it — April 21,1961, Bob Dylan and handed it to my mother.

“Thank you, Bobby,” she said, kissing him on the cheek.

He knew the moment he left I would be all over it, going through page by page as fast as I could. And that is exactly what happened. As soon as he departed the book found its way into my excited, 15 year-old hands…

Inside were Bob’s little scribblings and notations throughout. He had kept it in excellent condition. I thought the book was terrific; not sure if that was all about how it was written, or because Bob had owned it. Either way, the desired outcome was achieved.

An image of the inscribed book is featured in the BOB DYLAN SCRAPBOOK 1956-1966.

A History Lesson

History fascinated Bob. The discussions he had with my father during the time he called 28th St. home played a crucial part in his education…

Each had natural off the chart intelligence. While both may have had photographic memories, they didn’t flaunt it…They’d been born with it. What counted was their ability to disseminate a cogent and insightful analysis…My father had given me some history tips and ways of analyzing things, but he was my dad. I figured he’d always be around so my mind would sometimes wander elsewhere. When I saw how closely Bob and Kevin were paying attention, I did a complete turnaround…

My father started way back with the Egyptians, Hebrews, Greek philosophers and Roman conquests. His method of analysis served a dual purpose for Bob. It provided him with early validation, as well as giving him direction on adapting those methods to other areas of thought.

My father went through The Middle Ages, The Crusades, The French Revolution, The American Civil War, The Spanish American War, World War 1, The Russian Revolution, The Spanish Civil War, World War II, The Korean War…and almost everything in between…He always made it clear that others didn’t have to come to the same conclusions…Go do your own homework. Take in as much information needed on any individual subject, then make a decision. It may sound like a truism now, but back then, emerging from the 1950’s, it was still considered the norm to conform.

The landscape, of course, would not be complete without the inclusion of organized religion and its ever-present tentacles. It was interesting to listen to that part because in Bob, as well as Kevin, you had two full blooded, bar mitzvah-ed Jewish boys being tutored by a Scotch Presbyterian from Nevada, more versed in Jewish history than either of them. Rather than accept lessons he’d been taught in school, my father’s questioning nature led him from an early age to delve into the underpinnings of as many religions as possible. He went through them one by one. While they had different holidays and different ceremonies were their fundamental tenets all that different?…

Maybe “the answer is blowing in the wind” because not enough people ask questions. The shock and horror expressed by many when Bob appeared to enter his born-again Christian routine at the end of the 70’s puzzled my father. How else are you going to get answers unless you go to the source?

There was a natural understanding and deep bond between the two of them. It wasn’t until later I made one of the connections that explained why Bob had plugged into my father’s psyche and why my father spent so much time talking with him.

Bob originally represented himself as being an orphan from the Midwest hopping on freight trains to get from one place to another winding up in the big East Coast City of New York. While we all know now this was not true, the combination of his made-up-tales and real background turned out to be the real-life depiction of my father. This was not lost on Bob. As mentioned before, my father, born in 1904, really had been raised in an orphanage, was from a small western mining town, left college at 19, as Bob later would, and headed out to San Francisco. He hopped freight trains during the Great Depression and didn’t look back — at least not for 50 years.

In 1968 I visited Virginia City where my father was born, entering on an old steep road called the Geiger Grade, with a vast plain below and mountains in the distance so far away. While I didn’t find the orphanage my father had been placed in at the turn of the twentieth century, I stood in front of the small prairie schoolhouse where he had shared lessons with children of all ages. I could physically relate to the isolation and loneliness he must have felt growing up; a sudden and deep visceral connection to him.

Though much of the original town had been demolished and was now mainly a tourist attraction, I could still sense how it had been divided by class — the stately mansions in one area and the more rustic houses of “ordinary folk” in another. Every day, back in my father’s time, kids from both sides of town shared the schoolhouse, but outside of school hours the class system held sway. As a teenager, my father had fallen in love with the wealthy judge’s daughter; and she was sweet on him. But, there could be no future in that. This was literally the Old West and being there allowed me to grasp the early roots of my father’s political leanings, his passion for equality and his affinity for the American worker — and for all working men and women. To have remained in Virginia City would have been unthinkable for him. In 1922, at the age of eighteen, he got the highest exam scores in the state and enrolled at the University of Nevada.

It may seem odd that the great open spaces of the Mountain West would feel so claustrophobic to a young man, but it all made perfect sense to me. He felt locked down and had to get out and define his own place in the world. My father was the real-life embodiment of the characters who had lived the things that Woody Guthrie and John Steinbeck wrote about, and Pete Seeger sang about…

There were a couple of specific conversations between my dad and Bob that really stood out because of the changing expressions on Bob’s face. Once I remember Bob was talking about the burgeoning civil rights movement as if it were a unique generational thing, only to be informed by my father of the many bloody confrontations down South in the late 1930s, especially in the Louisiana gulf coast ports. They were for the right of NMU Union blacks and whites to share the same sleeping quarters when aboard ship. My father took out his original union membership passbook, which had all the dates stamped in it, illustrating how he was stationed in the Gulf area while the fight was going on — a first-hand eyewitness account. In the end it was a successful campaign and the NMU became the first union where black-and white could sleep side-by-side anywhere they shipped out from, or when they were in port on a layover. He finished that conversation by talking about a man he admired. It was Eugene V. Debs…

Debs was one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or the Wobblies), and five times the candidate of the Socialist Party of America for President of the United States. He was a great orator and Dad had studied his speeches. As he was winding down, he said to Bob in an even tone with great affection: “Bobby, if you can, remember this. It’s from one of Eugene Debs’ speeches. I want to pass it on to you. I read it when I was about your age and it stood me in good stead. You don’t have to take it literally from a political point of view. Think of it more as an allegory.”

Bob leaned forward.

I heard it as well, but could not remember the whole thing. Years later I thought about it and decided to look it up. When I found it, I saw Dad had quoted it exactly, word for word.

I am not a Labor Leader; I do not want you to follow me or anyone else; if you are looking for a Moses to lead you out of this capitalist wilderness, you will stay right where you are. I would not lead you into the promised land if I could, because if I led you in, someone else would lead you out. You must use your head as well as your hands, and get yourself out of your present condition.

Bob never forgot it.

Editor’s Addendum: Peter McKenzie points out the photo of “Bob and my father” on the cover of his book hints at the intimate, nearly familial, tie between them.