Review of The Auschwitz Album: A Book Based Upon an Album Discovered by a Concentration Camp Survivor, by Peter Hellman (Random House, 1981). First published in Aperture 89 (Winter 1982). Reprinted in Danny Lyon: American Blood: Selected Writings 1961-2020, (Karma Books, New York).

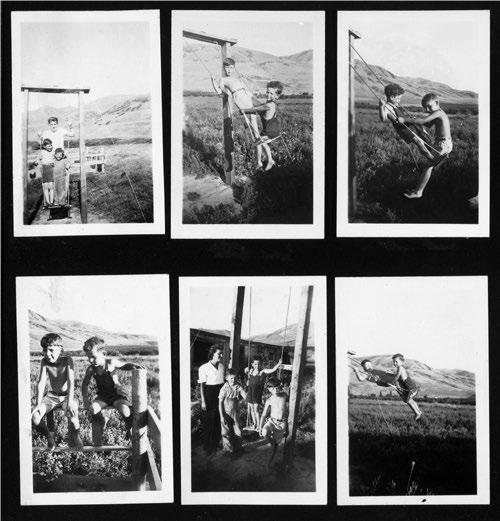

Page from album made in Perry, Utah, in 1944, by Dr. Ernst F. Lyon, German immigrant.

Like his father, Lyon is a compulsive maker of photo albums.

One day historians may look back at the first half of this century and see the photographic album as the quintessential form of expression. In its pages, carefully assembled by countless fathers, lovers, daughters—all photographers of sorts—they may find more of us, and our lives, lovingly and honestly preserved than in any other form. But in Nazi death factories the photograph albums of the arrivals were thrown in a heap and burned. After all, there would be no need for them, since their owners and all the generations of their families, older and younger, were about to be murdered.

Except for identification shots of incoming inmates, photography was not permitted in the concentration camps—even the Nazis realized that not everyone would approve of what they were doing. It must have been frustrating, though, not to be able to make a record of their work. Now and then the rules were broken. A few SS men couldn’t resist taking pictures as they tortured and slaughtered the Jews, the Poles, and the Bolsheviks.

Sometimes, when an SS officer took his roll of film to a local laboratory for processing and the technician assured him that no additional prints would be made, the technician did make additional prints anyway. A few have come down to us of what Hitler did not want photographed.

In Auschwitz, the death camp in Poland that alone exterminated more than one million people, mostly Jews, an underground existed, as one did in every concentration camp. Getting a camera was not a problem, because the condemned Jews brought them in as part of the precious personal goods they carried to their “resettlement.” But bringing a camera into Birkenau, the killing center and location of the main gas chambers and crematorium, was something else. The underground assigned David Szmulewski, an underground member working as a roofer in Auschwitz, to do it. Lying on the crematorium roof inside Birkenau with a camera and film, he made three exposures—all understandably a little shaky, slanted, and out of focus—through a hole in his shirt. One shows women undressing in the woods, just before they are gassed. The other shows the Sonderkommando, the living dead, the camp inmates forced to drag bodies to the outdoor pit to be burned. Afterward the film was smuggled to Kraków for processing and out to a world that was not particularly interested. And on June 26, 1944, a US Air Force plane flew over Auschwitz and made a photograph showing Birkenau, the gas chambers, and the trains.

One other person whom we know of made pictures at Auschwitz, and he was in a much better position to do so than the Jew on the crematorium rooftop or the Americans in the plane. He was an officer in the SS. Although his identity has never been established, the photographs he made show he had access to the photography laboratory in Auschwitz and that he was a fine photographer. Perhaps he, or someone of authority, finally yielded to an irresistible impulse. Such a fantastic arrangement for killing people, with trainloads of Jews arriving day after day, cried out for a suitable record. Perhaps it was Ernst Hoffman, the second in command at the lab. Or his boss, Bernard Walter, who rode around the selection ramp on his motorcycle. Perhaps he used a Rolleiflex, as the low angle of many of the pictures suggests. We don’t know; we have only the pictures, rescued from the photographer’s locker at the end of the war. The rest is a mystery. No one has stepped forward for the credit. Merely to have been seen on the ramp during the arrival of the victims is today a crime in Germany.

Whoever made this set of pictures carefully arranged them in an album, and gave it a title, an ironic one, “The Resettlement of the Hungarian Jews.” He gave it a beginning (two “studio portraits” of rabbis), a middle (the album itself, showing step by step the selection, the division of those who would die immediately that day, and those who would become slaves), and an end (he taped into the last page two pictures of crematoriums with the doors open, showing the ashes and bones inside). Like the great American photographers who saw the carnage of the Civil War and held in their hands, for the first time, the cameras that gave them the power to reproduce the scenes, this Nazi photographer produced, I hesitate to use the word, a “masterpiece.” He made a set of pictures that is unique and that stands among the most important made anywhere during the war.

The story of the album’s discovery and safekeeping is so amazing I leave you to read it for yourself. Its first edition of one thousand copies, published by the Beate Klarsfeld Foundation in 1980, was given away; one was given to me by my lawyer friend, Arnold Ostwald, in his office in Manhattan. It has now been reissued by Random House as a picture book called The Auschwitz Album, with a text by Peter Hellman. Hellman’s writing is powerful, sickening, and spellbinding, which it should be. It follows the destiny of one of the Jews who arrived in the trains that murderous spring of 1944 and was photographed along with her family. The personal slant to the story, part of which takes place in Miami, permits us to empathize with the tragedy documented in the photographs. Accompanying the plates are pieces from death camp and resistance writing. The last piece of text, facing a portrait of four people, two sisters, their mother, and a daughter, is the speech made by Stormtrooper Hossler to a group of Jews about to be gassed. Fully clothed, four women who have about ten minutes left to live look into the camera, which is placed low and carefully focused. For me the picture is as good as anything Diane Arbus ever did. The text reads, “On behalf of the camp I bid you welcome. …Now will you please all get undressed. Hang your clothes on the hooks we have provided and please remember your number. …Would diabetics who are not allowed sugar report to the staff on duty after their baths?”

After the gassing, which was not photographed, automatic elevators carried the bodies up to the ovens. When they were working full speed, as they were when these pictures were made, excess bodies were thrown into a fiery pit. Disposing of the bodies took much longer than killing, and caused delays, as trains stood waiting on the tracks.

Just weeks before the pictures were made, a special piece of track was laid so that the trains could come directly into Birkenau, unloading victims closer to the gas chambers in which they would be killed. The platform on which the arrivals disembarked was called the ramp. In the next few weeks, in May and June 1944, over one-quarter million Hungarian Jews would come to the ramp, and most of them would be gassed. It was during this time that the SS photographer made the pictures for his album.

Whenever he could, he avoided showing the guards. Perhaps his colleagues did not appreciate this camera enthusiast. As it turned out, twenty years later, some of the pictures were used as evidence against SS men who appeared in them. Overt physical violence is not shown. The undressing, gassing, and disposal of the bodies are not shown. The omissions almost make the work more powerful. We know what is going on, and of course the photographer did, too, and there is something horrible about that mutual knowledge, as if making us conspirators. He knew that almost everyone at whom he pointed his lens would soon be dead. Repeatedly, his feelings as a photographer overcame his lack of feelings as a stormtrooper. He was, as a photographer, in a perfect situation. Before him was a scene of literally unbelievable scope. His subjects, thousands of them, were everywhere, all around him. No one had ever been permitted to stand on the ramp with a camera. He alone had somehow achieved that privilege. None of the subjects dared turn away. Most of them posed, halting on their grim journey for a moment to have their picture made. Many young people even tried to smile. Perhaps they hoped to win favor with the officer, or they were embarrassed, or they thought what the photographer was doing was funny. He moved along the platform making pictures. The boxcars spit out a load of condemned humanity.

Of course, the truth of these pictures makes us sick—but it didn’t make him sick; he was engrossed in his work. Repeatedly, he climbed atop a boxcar for a better view, to show the now infamous selection, the men and women being separated. On one day the sky becomes overcast, and his pictures are now perfect. The doomed stretch five abreast along the train, the SS stand idly, slightly bored, waiting to get on with the process. Those to the left become slaves, those to the right die that afternoon. The photographer moves closer to make group portraits, the most difficult kind to make. Even his reflection does not show in the spectacles of the men he portrays. He has true anonymity, the key to great photography.

Hellman says a great deal about these pictures, and every word of his text is worth reading, but, as with all good photographs, words are inadequate for these portraits. What sympathetic contemporary writer shows the tragedy of these times, our times, as movingly as these portraits made by a Nazi?

“Women on Arrival” reads the album section title. Women with children, and children, all will die. In the first picture the editors have used here, a handicapped child poses with the children near him, a cross between a portrait and a family snapshot. Lewis Hine in the factories, Walker Evans in Alabama, pale before this stuff. The ultimate family photo. Half an hour after the picture was made, everyone was killed.

“Able-bodied” men and women were preserved—as long as they remained healthy and useful—for slave labor. This section contains one of the greatest multiple portraits of women I have ever seen. Six of the women’s faces can be clearly seen, as in a portrait. Some look into the camera, some look away. Each is distinct, strong in character, different, beautiful, a person, a Jewess, a woman. Maybe the Nazi photographer talked to them. Maybe he liked them. The book contains one photographic masterpiece after another, but, of course, this book is not about photography; it is about Birkenau and the extermination of the Hungarian Jews.

“No Longer Able-bodied Men,” “No Longer Able-bodied Women and Children”—the people in these pictures are on the way to the chambers. A woman resists and struggles with three men, perhaps with her husband. Her instincts are better than his. Shadowy SS men move through the woods behind. They struggle right before the cameraman. But this isn’t Hollywood. This is real. People are walking, with their children and with their bundles, to die. You wish these pictures were unbelievable. Unfortunately, they are not.

Men and women are shown after delousing. They will survive a while as slaves until they succumb to starvation and disease. These pictures are not as good as the others. The sun is shining. Maybe the photographer is not as interested. The “Kanada” slaves working for the Nazis rifle through the belongings of everyone brought to the ramp. Anything useful is sent to Germany, a potato is stuffed in the mouth, photo albums and other useless items are burned.

Then comes the last section, “Birkenau.” These are the greatest pictures in the book and, I think, some of the greatest photographs ever made. Birkenau means “birch grove.” It is the same spot at which the underground member David Szmulewski was able to photograph from the crematorium roof. The people here are all selected for the gas chambers. They are awaiting their turn to die. The trees, the children, the women in their babushkas of various fabrics, the families trying to stay together, sitting on the grass—the photographer watches them, photographs them. Some children look at the SS man with the camera. He knows what he is looking at. Perhaps the children hope he will give them some water. A little girl looks at the photographer. Had she survived she would have been about my age now. Against all odds, this album did survive.

It is not a book that can be taken lightly. In a sense—and I mean this as a compliment—it is not a book at all. It is something I am a little bit afraid of. When I put it down, I am conscious of what it touches. For instance, I never put it beneath or over my own family album. I am afraid some of the evil will seep through. But having the book and reading it is not altogether a negative experience. It does exist. This did happen. There are those who argue that, in parts of the world, in different ways, it still happens. The least we can do is to know about it. When we put the book down and look at the sunlight streaming through the window, how glad we are to be alive.

Danny Lyon’s blog is bleakbeauty.com and his instagram is http://instagram.com/dannylyonphotos.