I shall describe and attempt to interpret a difference in representations of war in two television series made by the same people about the same war, Band of Brothers, which aired in 2001, and The Pacific, which aired in 2010. I hope to show that despite influential argument to the contrary—most notably Paul Fussell’s celebrated The Great War and Modern Memory—it is imprudent to make strong historicist or contextualist claims that the transformed nature of war since 1914 is a sine qua non for explaining modern ironic and anti-heroic representations of combat.

Band of Brothers was inspired by a 1992 work of popular history with the same name, one in which Stephen Ambrose told the story of a company of parachute infantry from its training through the end of the Second World War in Europe. Both the book and the miniseries contain episodes recounting the parachute assault that preceded D Day, which was both the first and the only successful mass parachute assault ever attempted, a subsequent battle four days later, a massive, famous and failed drop in the Netherlands, the siege of Bastogne, a defensive battle in Alsace, and the collapse of Germany. Band of Brothers premiered on September 9th, 2001, and was in general brilliantly reviewed, but the first reviews appeared before the premiere—the Times review, for example, appeared on September 7th. On September 11th HBO immediately stopped advertising the program, and its final episode had approximately half the number of viewers its first, ten weeks before–five million rather than ten. It was nominated for twenty Emmys, of which it won seven, along with a Golden Globe, a Peabody award and a number of other honors.

On the strength of crowd-sourced assessments, IMDB terms Band of Brothers the second highest rated miniseries ever made. There is some evidence that its resonance persists: when in 2013 an Irish critic wanted to describe a German Second World War miniseries seven years in the making–Unsere Mütter, Unsere Väter–he perhaps ironically dubbed it Band of Brüder. I think that an indirect example of its resonance appears in the opening credits of the dystopian alternate history series The Man in the High Castle, in which a vision of plangent and eerie beauty in Band of Brothers’ opening credits—footage of parachute canopies floating down in a mass drop intended to evoke the one that began the liberation of France–is ironically repurposed to depict a successful German parachute assault on the United States. Parody presupposes familiarity, and blasphemy sacrality.

The Pacific, a companion piece to Band of Brothers, was filmed in 2007 and 2008 and released in 2010. It remains the most expensive miniseries ever made, costing perhaps twice as much as Band of Brothers, and while it was a succes d’estime, nominated for 24 Emmys and won 8, along with a Peabody award, it was a commercial disappointment. Despite a vast advertising budget its first episode was seen by three million viewers rather than the ten million who watched the premiere of Band of Brothers, and its finale by fewer than two million, rather than more than five million who watched Band of Brothers’ conclusion. The Pacific is based on three memoirs, most famously Eugene Sledge’s celebrated With the Old Breed and Robert Leckie’s equally admired Helmet for my Pillow. Leckie’s book describes the fighting on Guadalcanal and Peleliu, and Sledge’s the fighting on Pelelui and Okinawa.

While the two miniseries depict the same war very differently, neither is consistently reverential about American virtue in wartime. Both show American atrocities—the murder of P.o.W.s–and The Pacific shows Japanese and American soldiers mutilating the dead and dying. Band of Brothers, the more optimistic of the two, nonetheless spends three or four of its ten hours dramatizing the failures of two very bad American officers, one apparently sadistic and clearly incompetent, the other possibly cowardly and clearly incompetent, later suggests that one supremely competent American officer is probably a murderer and certainly a looter, and one of the Marine officers in The Pacific steals from his men. Both series show horrific wounds and gross, unsentimentalized physical distress of other kinds, and both trace the demoralization, brutalization and psychological erosion of troops as the war grinds on. The most striking difference in the ways American troops are depicted in the two miniseries lies in The Pacific’s attenuation, and for a crucial moment its apparent destruction, of the link between suffering and agency in war.

Samuel Hynes, the greatest scholar of Anglo-American war memoir and the author of a very fine one, noted that the experience of combat was generally remembered as morally significant precisely because it was linked with political and historical agency. While combat was also remembered in ways that broke the link between personal qualities and individual outcomes, which put ironic pressure on traditional conceptions of the heroic, personal qualities were still linked to the collective achievement of a vast and urgent purpose.

To put this somewhat differently: Augustine famously observed that what matters is not that we suffer, but how we suffer, that the same shaking that makes fetid water stink makes perfume smell the sweeter, and the same fire that makes straw smoke makes gold gleam. In the 20th C. war memoir there is a tendency to understand the experience of war at least as much in suffering violence as in inflicting it, with a redefinition of heroism to denote how we suffer. Like much 20th C. war literature, Band of Brothers and The Pacific note the differences in how men suffer—straw smokes, gold gleams–but Band of Brothers creates causal and moral order when the terrible suffering of American paratroopers defending Bastogne is within months followed by their liberation of one of the sub-camps of Dachau. In The Pacific, by contrast, while Marine suffering on Guadalcanal is belatedly understood as heroic and historical agency, their suffering on Peleliu, Iwo Jima and Okinawa seems eerily disconnected from the outcome of the war: it makes men worse, and does not make history better. In the case of Peleliu, we learn that the dreadful campaign was a strategic blunder, so that the suffering men endured there was in military terms wholly meaningless. At the end of sequential episodes we learn Peleliu, Iwo Jima and Okinawa were all taken, at horrific cost, to secure airfields that would never be used, and when this terrible fighting comes to its end, The Pacific shows surviving Marines on Okinawa learning of Hiroshima in a scene implying that the war would have ended exactly when it did had Okinawa never been taken.

When I first saw The Pacific and noticed this difference from Band of Brothers my intuition suggested a simple explanation for it: Band of Brothers was made before 9/11, whereas The Pacific was filmed in 2007 and 2008, during the least successful period of the American war in Iraq, when the Sunni insurgents looked as if they would outlast the Americans and destroy an elected Iraqi government. By 2008 American understanding of the experience of American combat troops included our soldiers’ suffering as well as their infliction of suffering, but did not at that moment necessarily include any great conviction that the suffering of American soldiers had achieved any desirable historical outcome. Suffering thus became almost the whole of the story, which is the way Europeans have tended to depict war since 1945. It is certainly the way Unsere Mütter, Unsere Väter depicts both the suffering of soldiers and their agency: their suffering creates nothing, and they are almost wholly bereft of either moral or political agency.

Other differences between Band and Brothers and The Pacific at first sight seemed similarly explicable in terms of the experience of the Iraq War. On Guadalcanal the Marines in the miniseries encounter a case of perfidious surrender, which makes one variety of subsequent American atrocity inevitable—soldiers are unlikely to risk taking prisoners known to engage in perfidious surrender. Starting on Guadalcanal, the startling alterity of Japanese combatants is suggested by Japanese tactics, which are almost incomprehensible. While there are a couple of glimpses of common humanity, The Pacific depicts a war with people one cannot understand; literally as well as figuratively, there is no common language.

Band of Brothers, by contrast, concludes with a scene dramatizing the partial moral intelligibility of German soldiers: a German general honors his defeated troops in language at least some Americans can understand literally, and all seem to understand when it is translated. In Normandy, the Netherlands, Belgium and France the Germans are dangerous in a straightforward fashion, in the same ways that the paratroopers are dangerous to the Germans, but on Okinawa the Marines encounter an involuntary suicide bomber, which seems an unmistakable allusion to Iraq. Band of Brothers at times dramatizes tactical finesse, showing it prevail against long odds on D Day. The Pacific instead stresses the chaos of violence in alien environments. Tactical skill seems less relevant to the outcome of the war on Guadalcanal, Peleliu and Okinawa, just as it seemed less relevant in Iraq in 2007.

On this reading our collective assimilation of the historical experience of the Iraq War allowed our representation of the Second World War to become more modern, in the sense that Paul Fussell used the word modern in The Great War and Modern Memory. What Fussell took to be the obvious political futility of the First World War and what he took to be its tactical and strategic idiocies meant that only in the wake of a disaster did we acquire the capacity to represent war with the strongly ironic sensibilities he so valued. Fussell had a tendency to assess modern war literature that depicts war on the grounds of how ruthlessly and insistently ironic it manages to be, and thus condescended to David Jones’ dazzling In Parenthesis on the strength of its recidivist if sporadic interest in older epic forms when representing war. Fussell would almost certainly have greatly preferred The Pacific to Band of Brothers—in his own last, very short book about the Second World War in Europe, The Children’s Crusade, he seems grudging, almost irritable, about the possible political and historical agency suggested by the late war discovery of the concentration camps the Americans child soldiers had shut down.

But other explanations for the difference between Band of Brothers and The Pacific are also possible. Both Sledge’s and Leckie’s memoirs are strikingly darker than Ambrose’s book ever gets. Neither includes anything like the liberation of a concentration camp, nor the liberation of anything; had Sledge or Leckie fought in the Philippines in 1944, or seen and recounted the post-war construction of a Japanese democracy, the miniseries might have had a different tone. The progress of the war in Europe between D Day and VE Day is also immediately comprehensible as a linear and necessary progress, whereas the progression of the island fighting in the Pacific isn’t. But my initial theory that our experience of Iraq was the prerequisite for a subversive, savagely ironic, anti-heroic representation of the Second World War seems doubtful for other reasons, not least because ironic, anti-heroic responses to the war were pretty visible while it was being waged, and not only at our cultural margins.

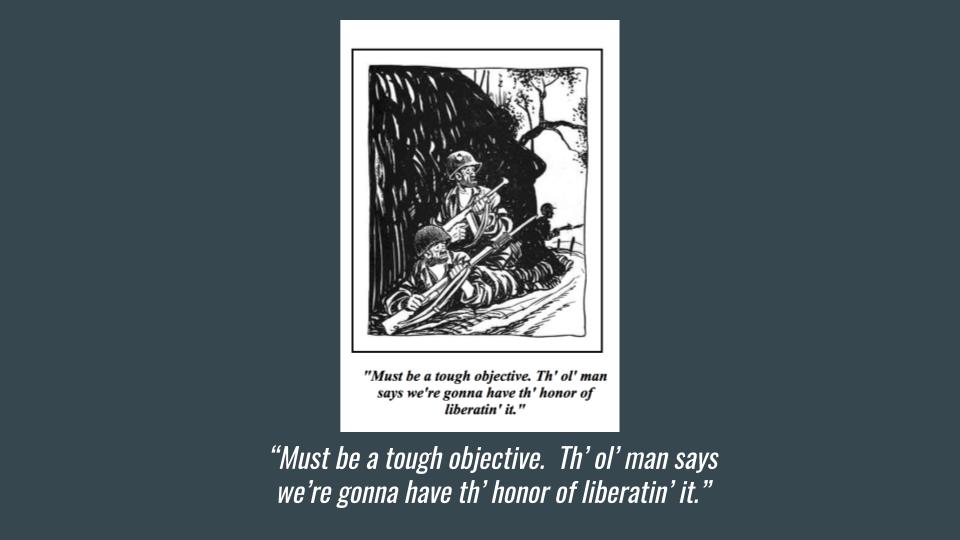

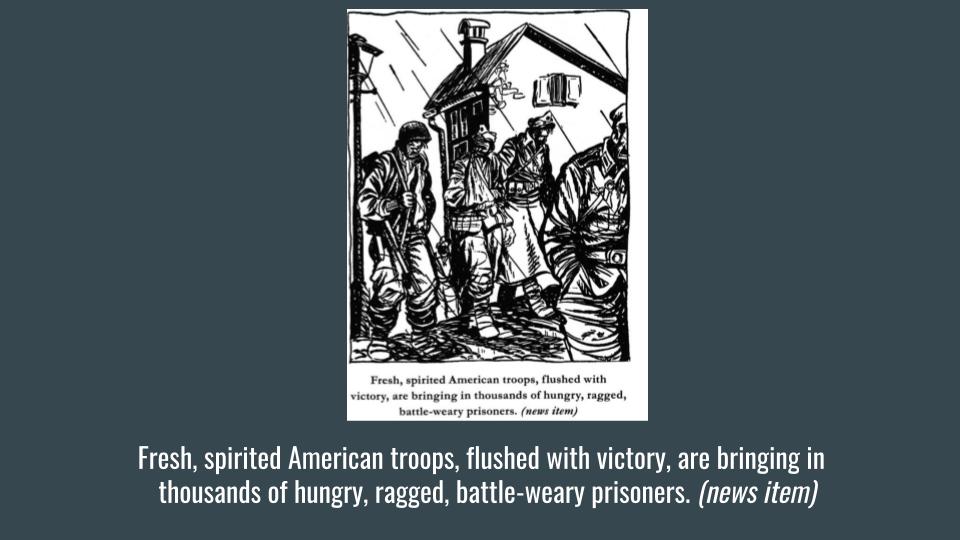

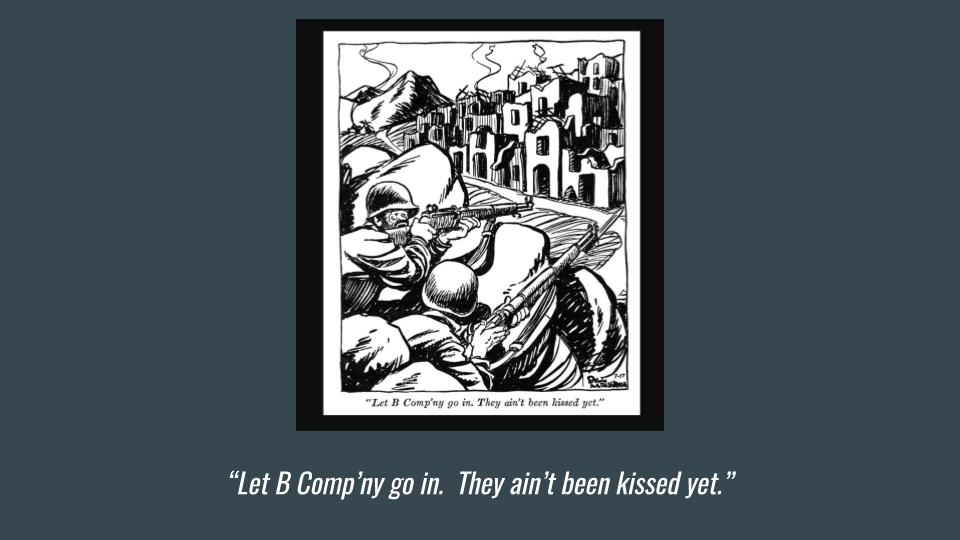

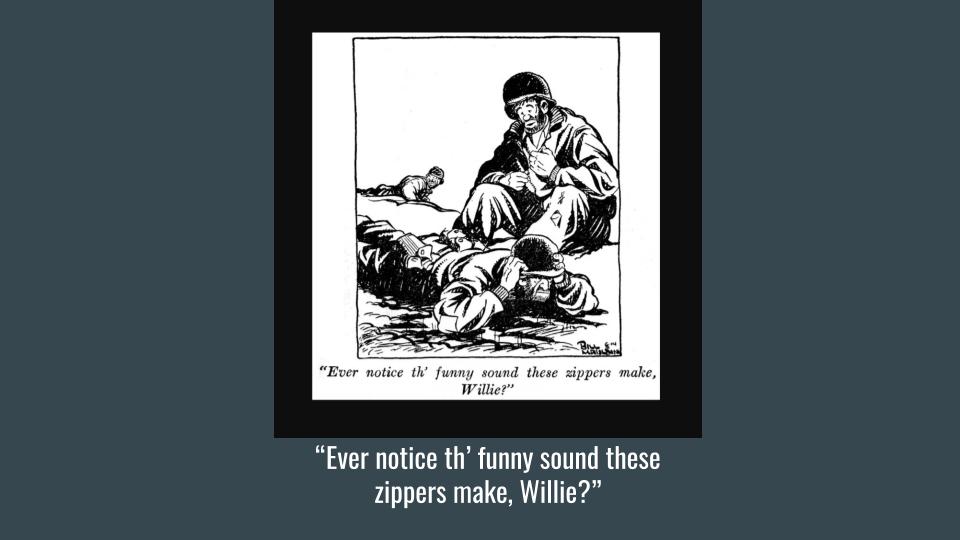

I draw your attention to these works by the soldier-cartoonist Bill Mauldin, which were published in Stars and Stripes, the Army’s newspaper.

The first mocks one of Fussell’s richest targets, the deceitful bombast of the failed heroic and epic language of military authority, and the second shows how this language can be ironically redeployed against that authority by its intended victims. The third subverts a trope–the equivalence of sexual and martial experience–that was used to glamorize both the Second World War and a number of others: Mauldin suggests that personal knowledge of combat is not to be envied, since by the end of it one is likelier to have been kissed by death than by exuberantly grateful Frenchwomen. The fourth cartoon suggests that contextual knowledge can be indispensable for making sense of a contemporary representation of a particular war. The necessary contextual knowledge is that the sound of a drawn zipper on a newly issued field jacket resembled the sound made by a detested and deadly German automatic weapon—probably an MG 42—and in the cartoon that sound made by a soldier playing with the zipper triggers an acquired instinct to dive to the ground the moment one heard it.

But while contextual knowledge allows access to the cartoon, the interpretive technique that actually illuminates it is Bergson’s theory of inelasticity. The cartoon argues that while we are often told that personal experience of war, like personal experience of sex, is the knowledge that marks an adult male and makes us envy and admire him, in this case the knowledge of war makes men ridiculous, because the condition of inelasticity is the essence of the laughable: in it a thinking man is reduced to a ludicrous because inelastic and thus unthinking animal. The automaticity of instinct preserves animal life but destroys human dignity, and for a moment, at least, the knowledge of war paradoxically and ironically only makes men ridiculous. Bergson’s theory preceded the first world war–it was published in 1900–and while deeply if not invariably useful is itself an anti-contextual theory, for Bergson thought inelasticity explains comedy in all times and places. So some theories that predate modernity’s wars may be indispensable for understanding the point of some great art made during and about those modern wars…and some theories that stress the radical uniqueness of war in modernity may sometimes lead us to wrongfully deprecate something important in some art made about those wars.

Perhaps Mauldin’s cartoons can be fitted onto at least a Procustean contextualist bed. After all, if Fussell is right in his larger claim, Mauldin, who drew and wrote a generation after the First World War, may have been able to perform his ironic, anti-heroic work on the strength of the diffusion of the ironic sensibility of the literature that emerged from the First World War. Samuel Hynes noted in his study of memoirs of the Second World War that their authors were steeped in the cultural memory of the First World War–they arrived expecting to be unsuccessfully deceived and then thoroughly disillusioned. So if Iraq didn’t do it, did the First World War, or perhaps Vietnam, or a submerged memory of Korea, prepare the ground for the work of The Pacific?

Let us return to a text. The St. Crispin’s day speech, Henry V Act IV scene iii, which gives Band of Brothers its title, is probably the most famous war poetry in our language. Henry V, believed to have been written in 1599, is often invidiously contrasted with Henry IV pts 1 and 2–deprecated as a species of apologetics for a brutal episode of imperial aggression, although rarely in such bald terms. Near the end of Band of Brothers a surviving paratrooper recites a piece of the St. Crispin’s Day speech, celebrating warrior prowess, the supreme happiness of comradeship, and the reward of immortal memory. But this interpretation of the speech may not suffice as an interpretation of the entirety of the play of which it is a part.

My sense is that with both Hotspur and Falstaff dead the playwright deploys other resources to construct an intermittently ironic and subversive account of that famous Lancastrian victory. To pick two examples, there is the brilliantly ambiguous possessive pronoun in the report of Falstaff’s death: ‘The King has killed his heart” (Act II scene i) which may suggest that at Harfleur the King has become strikingly heartless–Bardolph would probably agree–and there is also the savage joke exploiting the alleged Welsh tendency to confuse labial plosives when speaking English and mentally translating from Latin, so that Fluellen compares Henry not to Alexander the Great but to Alexander the Pig, that cannibal omnivore notorious for wanting more than its share (Act IV scene i). I do not think Henry V is in its totality an ironic and subversive argument about imperialism and war, only that the invocation of contextualist arguments to resolve all difficulties in reading Henry V as an ideological defense of war and imperialism is equally implausible, and a better understanding of the laws of and customs of war with respect to a practicable breach does not require us to conclude that English soldiers are unimpeachably free to “Defile the locks of your shrill-shrieking daughters; Your fathers taken by the silver beards, And their most reverend heads dash’d to the walls, Your naked infants spitted upon pikes, Whiles the mad mothers with their howls confused/Do break the clouds, as did the wives of Jewry”.

Ironic and subversive representations of war and the heroic may begin with the Iliad, the text to which Shakespeare seems to be alluding above. A theory that requires us to assume that historical distance from a work of literature is an insurmountable obstacle to a non-specialist reader being made wiser about urgent things probably makes defending the value of the humanities a more daunting task than it need be, similarly a theory holding that literature means something urgent only when it means something we already know from somewhere else.

Finally, on my paper’s title: Quentin Skinner, whilom Regius Professor of the history of political thought and an influential exponent of contextual reading, was once assessed by a witty critic as a man whose theory of reading made his own subject no more than a guided tour through a graveyard. This was not intended as praise of strong contextualism. I think that old representations of war have provided us with a guided tour through many graveyards, and in a more useful fashion than an excessively strong historicist contextualism implies is likely, or even possible.

(Adapted from a paper given in honor of the retirement of Karen Lawrence from the Presidency of Sarah Lawrence College.)