Marsha Music née Battle is a writer of rootsy, elegant pieces on time past who grew up in Detroit, daughter of a pre-Motown record producer father. Her blog means to capture the vibrant, creative years of mid-century Black Detroit life before memories fade and the city “changes” once more. She regards the music of Detroit as an historical chronicle, reflecting the city’s importance during the American Century. Your editor came upon her posts through a link on YouTube following an upload of the 14 year-old Aretha Franklin singing “Never Grow Old.” That performance was produced by Marsha Music’s father, Joe Von Battle, who was the first to record Aretha.

Von Battle established a tight connection with the Franklin family when he began recording C.L. Franklin’s sermons in 1953. (Note the advertisement in the photo of Von Battle’s record store on our homepage.) Marsha Music’s “requiem” for her father “the record shop man” who lived large on Detroit’s Hastings Street is one of her many posts that seem to call and respond to David Ritz’s account of the Franklin family’s life and times in Respect (see review above). Another piece, though, sublates Ritz’s inside dope on gospel royalty. Marsha Music gets even nearer the spirit when she riffs on BeBe Winans’ CD Cherch: “spelled that way to capture the phonetic distinction that we make between Black and White “church”–or, even more specifically–between Black Sanctified/Holiness/Pentecostal/Church of God in Christ (COGIC) church, and the more formal, less demonstrative Black church services (that are actually diminishing in numbers these days, in favor of much more emotional ‘Praise and Worship’).” Cherchmoves our Sister from Detroit to evoke her own COGIC experience of worship and praise-songs, which soundtracks BeBe’s since their families have sung and shouted together in the same neighborhood church. Marsha Music underscores that experience is a collective thing—the antithesis of celeb-mongering:

It occurs to me in this writing that some of these songs…are almost secret songs, lacking exposure to the mainstream record world, and I have a sense that down through the years there may have been a reluctance about releasing them as records, as if to do so would give up yet one more element of African-American spiritual power.

She contrasts Cherch’s songs with the sort of gospel entertainment that puts the spotlight on grand individual performers or starry groups. Cherch doesn’t go there—its songs are meant “from the first note, to resonate through a congregation and place it ‘on one accord’.” Marsha Music muses on that affirmation:

In fact, the clarion song of most Black Holiness churches is called just plain “Yes,” with a series of instantly recognizable notes. This one word chant is sometimes jokingly called the national anthem of the COGIC. The lyrics consist of that one word, embellished by little more than cries, shouts, key changes, and embellishments of exhortations to praise, for as many stanzas as required by the collective spiritual consciousness i.e. The Holy Spirit–of the church.

This is in synch with the finding of an eminent anthropologist, Roy Rappaport, who once suggested all religions come down to groups of people saying…yes.

Marsha Music, though, isn’t just a yes woman. One of her most compelling pieces is hermeditation on her dozen years working in Detroit factories, which reminded me of her late homeboy Philip Levine’s poetic resistance to dead time. I bet he would’ve identified with her escape artistry. A glance at the following piece hints Marsha Music wasn’t born to conform. She had her own angle on life, her own tendency in time even before she was a grown woman. B.D.

A Black Woman Remembers Elvis

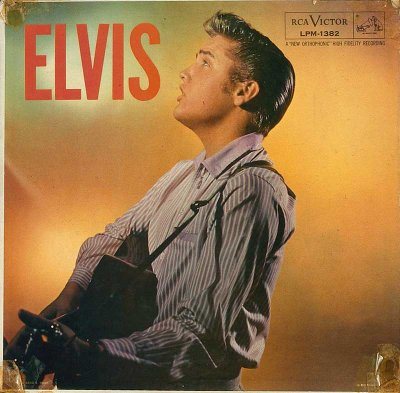

Elvis was my first love. I was 5 years old in the 1950s, and I sat in the sun on the living room floor with my legs criss-crossed, album cover on my lap, in a pool of light from the leaded-glass window near the fireplace. Motes of dust bounced and drifted in the beam of sun, fairy-like. The sun shined on Elvis Presley too, on that cover; guitar strapped across his stripe-shirted shoulder, as he gazed upward into a faraway sun, or maybe into the light of Heaven itself.

I was besotted by such beauty in a man. The errant forehead curl, the pull of his lip that made the tiny sneer; imperfections that rendered him more beautiful. The sun was golden and Elvis was too. Yes, he was tawny then from a life in the Delta sun; his hair a slick, golden crown. This was years before his hair was dyed black for photos and film, and later, to hide the signs of time. Oh yes, back then, as I gazed at the album cover in my living room, he was a golden boy. He is Elvis, the light shines on him, and it shines on me.

There is a familiarity about him, a softness of speech and manner that is not unlike my own Southern father and uncles. There is none of the frantic crispness, the stiff, staccato notes of the North. No, his way is soft; he moves more like folks move in my world. I am 5 years old, yet I know this. There is too, an oddness about him, something untold. I learned later of a twin who died still born, and oh, the mystery of that child unknown. Another Elvis in the world was too much to contemplate. Maybe the spirit of the long gone child made Elvis become more than if they had both survived. His too lush beauty hints, to me, of long-lost secret ways, his eyes too heavy, lips too full, the nostrils spatulate. I wonder just what other blood flowed in those Delta veins, what long ago dark ancestor through him sweetly sang.

My daddy was a record shop man. Produced, wrote, recorded, pressed, published, and sold records. Growing up, I was surrounded by records, and as a child, I read album covers and liner notes—my earliest history class of the world and the people in it. Our house was full of records, 45′s, 78′s and the new “LPs”. Records were recorded even in our living room, the high, oak-beamed ceilings made for great acoustics. There were records all around—Stan Kenton and Oklahoma! and Bobby “Blue” Bland and Jerry Lee Lewis and Louis Jordan and Dinah Washington and Chuck Berry and Carl Perkins and Howlin’ Wolf and Peter and the Wolf and Mahalia Jackson and Tennessee Ernie and Ike and Tina and…, well, a whole lot of albums were in our lives. But the Elvis album cover I will never forget.

Years later it would be said that Elvis was a thief, a robber, a usurper of the music of others. But I think not. The men I knew, Black blues-loving Detroit men who lived in the North and hungered for their South, looked at him with the bemusement of affectionate elders, as if one of their own had played a trick on old Jim Crow. “Listen to that boy” they’d say, and shake their heads, “just look at him.” He was as familiar to them as sugar cane and red dirt. They knew just where he came from, just what kind of church he must have sat in as a child, by the way he played a chord, or sang a note.

They knew he’d seen that Holy Ghost grab someone and make them whoop and holler, in the churches of mothers’ boards and deacons, the churches of the gospel shout and stomp. Wasn’t his fault that there were those who made money off of the music of others, that society let him bust through musical doors that barred his darker brothers. He let rhythm music come through him, past the restraints of upbringing and environs. He didn’t turn our music white, but worked it through the channel of his own Delta life. Though how tortured was his wrestle with the secular and divine; oh, how tragic was his price.

I miss Elvis, even the jump-suited Las Vegas Elvis, the latter-day bloated and drug addled Elvis—yes, the eternally impersonated Elvis. But most of all, I miss the Elvis on that old album cover—the striped-shirted, tawny-haired, golden boy Elvis; with a profile as chiseled as Michelangelo’s David, his face as angelic as Gabriel, eyes raised towards Heaven. He’s the Elvis in my living room, with the sun shining on him, and shining on me.

[Photo above is from the 1956 album Elvis]