A folklore professor from the Ivy League was scowling when he came up to me at the 1969 meeting of the American Folklore Society. He stabbed a finger in my direction and, without a hello, said, “There’s one thing I can never forgive you for.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“You wrote the liner notes for Phil Ochs’ album.”

“What’s wrong with that?”

“That’s not authentic folk music,” he said.

“Who cares?” I said.

He obviously did. He arched an eyebrow and stalked off. Some academic folklorists were like that in those days. It was okay to write about a guy in a Kentucky holler who had a song he remembered or thought of, but it wasn’t okay to write about a songster who’d been born in Texas, had gone to military school and then to Ohio State University. Academic folklorists wrote countless articles and books parsing such distinctions

Phil and I met at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival. It was his second time there as a performer. His first album, All the News That’s Fit to Sing, had come out to very good reviews a few months earlier. He was walking around tossing a baseball into the air and catching it with a well-used fielder’s mitt. I had in the trunk of my car the fielder’s mitt I’d had since I was a kid. We played catch until the leather thong that held the webbing in place in my mitt disintegrated, after which the mitt was useless, so we just talked.

I was then living at 28 Holden Green in Cambridge, a row house in a complex for Harvard graduate students and visiting faculty. It was cheap; two stories above the ground and a finished basement below. That basement was great: I could write deep into the night, playing music as loudly as I liked without bothering anyone, and, on other occasions, I could record visiting friends (like Phil and Skip James and Al Wilson) without any intruding sound from the world outside.

When Phil had a gig in the Boston area, he’d often sleep on our couch. Most of the times he visited, he’d have a new song, either one he’d written or one he was adapting, like Alfred Noyes’ “The Highwayman” or Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Bells.” If it was a new song he’d written, he’d show me the words and ask what I thought of them as poetry, then he’d sing it and we’d talk about what worked and what maybe didn’t. When he asked me to write the liner notes for his second album, I Ain’t Marching Anymore. I was delighted. Phil was married then. I liked and admired his wife, Alice. They had been friends since they were students at Ohio State. They had a young daughter, Meegan.

Beatles ’65 came out and they were all Phil could talk about. I was unsympathetic. “That’s just noise,” I said.

“Have you listened to them?”

“I’ve heard them on the radio.”

“Have you listened to them?”

“No. Why would I want to? It’s just noise.”

He came by with Rubber Soul. “Just listen to this and then we’ll talk about it.”

“No, I’m not gonna.” He put album on the kitchen table and left. Every so often, he’d ask me if I’d listened to the album yet. I’d say “No,” and he’d look at me as if I were an idiot.

Then, at least six months after Phil had left the album on the kitchen table, I listened to it. I listened to it again. I was incurably hooked. I talked about them to anyone I could get to listen.

One winter night, Phil turned up accompanied by a guy wearing a cowboy hat. “I brought Jack,” he said. I was just home from a seminar I’d been teaching that semester with a psychiatrist friend, Norman Zinberg.

“Jack” performed under the name “Ramblin’ Jack Elliott.” I had two of his records. I’d seen him perform, but we’d never met. Jack had started out in life in 1931 as Elliott Adnopoz, son of a Brooklyn Eastern Parkway surgeon. I’d started out five years later and two miles away in a far less plush part of Brooklyn, Bedford-Stuyvesant. When Jack grew up, he decided he wanted to be a cowboy singer, so he gave himself a name that was a better fit. Every time I’ve seen him since—and in just about every photograph I’ve seen of him since—he’s been wearing a cowboy hat, and, most times, a bandanna around his neck. I don’t know if Jack has ever been near a cow.

Phil had a gig that winter night at the Unicorn in Boston, one of the two key folkie clubs in the area. The other was Club 47, in Cambridge. Jack was not part of the event; he and Phil were just hanging out at the time. When it got time for Phil to go to work, Jack said to me, “Are you going over there?”

“No,” I said. “Not this time.”

“Well,” he said to Phil, “I think I’ll stay here and rap a little while. I’ll meet you later.” Phil left and Jack said, “I hope you don’t mind my staying.” I said it was fine with me. “Good,” Jack said, “because you’re a psychiatrist and there’s something I want to ask your opinion about.”

“I’m not a psychiatrist,” I said.

“But you know those people,” Jack said, “and that comes to the same thing.”

“No, it doesn’t.”

“Well, it’s good enough for me.”

“All right,” I said.

“Do you think there’s anything odd about….” I have to stop there. Jack talked without pause until Phil returned four or five hours later. He asked several interesting questions and told me several great stories, some of which I wrote down so I wouldn’t forget them. I can’t tell you any of them because of HIPAA. We psychiatrists, real or phony, play by the rules.

Jack came by early one Saturday before a gig he had in Boston. We talked a while about what had happened to whom since we last talked. He told me Phil and Alice had split up. Then we sang some songs. The songs were just going back and forth until he sang Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice It’s All Right” which, for several reasons fit him so well and which he sang with so much pain and understanding and mésure that I sat there astonished and moved. Jack, I thought, was equally moved: things came together in that moment.

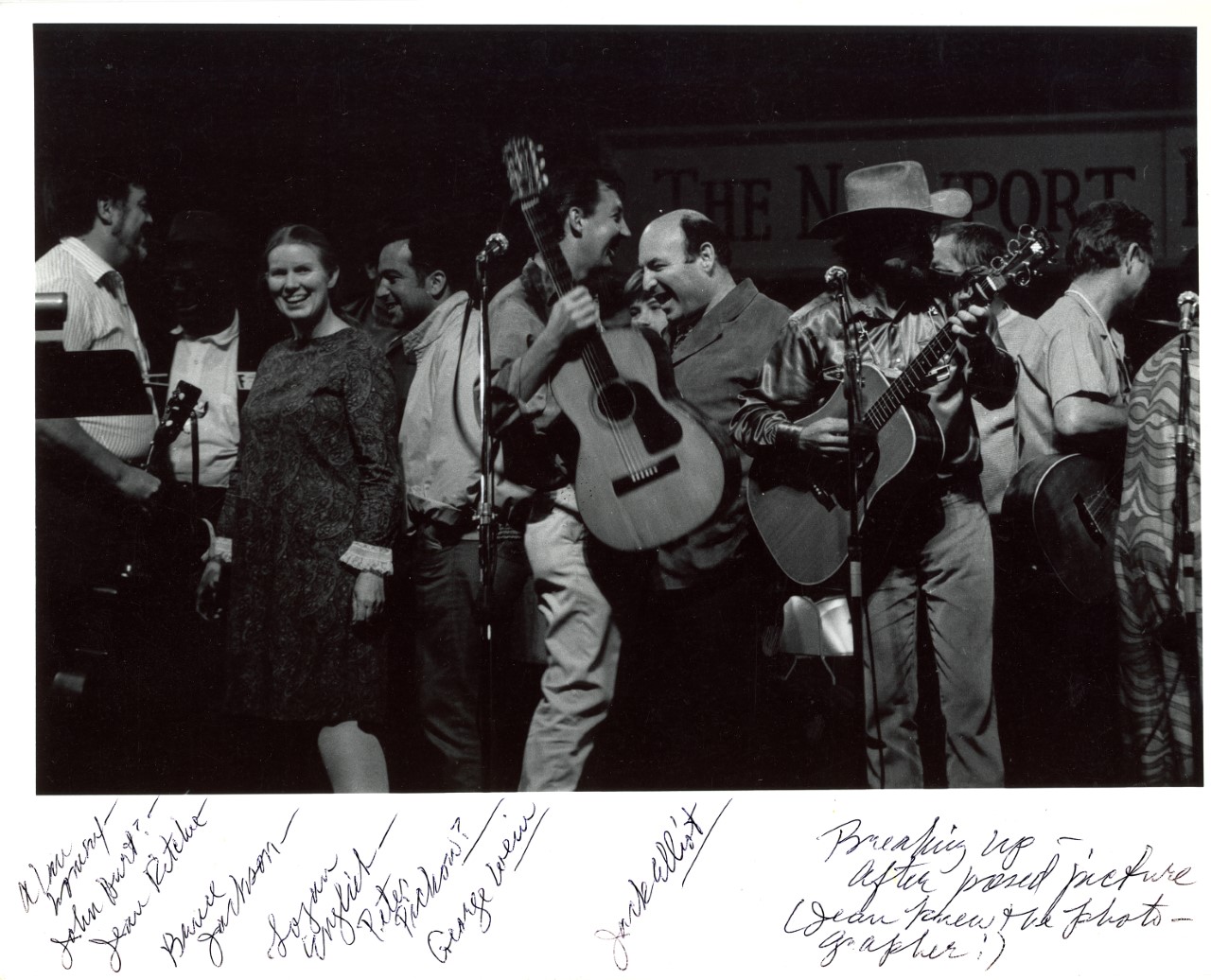

Arlo Guthrie, Rev. Frederick Douglas Kirkpatrick, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Pete Seeger. Woody Guthrie Memorial Concert, Newport Folk Festival, 1968. Photo: Bruce Jackson

“You know something that’s terrible,” he said. “Nothing ever dies. You put it in the closet, but it’s always there. And you know it’s there.”

“And,” I said, “it’s hard not to open the door once in a while just to make sure.”

“Yeah. James Dean thought I was the only guy in Hollywood doing what he wanted to do, just strumming my guitar. I sang to him in a parking lot one night. He thought I was real cool. Of course, I wasn’t.”

He told me of a time after a performance when everyone was going to a party and he was to go but no one bothered to tell him where it was. So Jack found himself alone in the darkened club with only two of the service people there. He talked with them until dawn, then brought them up to his place in the hills where he gave them the bed and took himself out to the grass and went to sleep naked. He woke up with a vicious sunburn.

A few weeks later, Phil turned up at 28 Holden with a gorgeous companion who seemed to know nothing about anything, who got none of anyone’s jokes, and responded to most questions in monosyllables. I didn’t know what was going on, but It seemed a bad trade had taken place.

I next saw Alice at the Newport Folk Festival. She was adorned with Nikons and light meters. I said, “Hi, how you doing?” and she said “Fine,” and I said ‘How’s Meegan?” and she said “Fine. We’re both holding up.” I asked if she’d seen Phil anywhere. She said she’d heard he was around and there was something she wanted to ask him about.

I said I hadn’t seen him. I said, “You making it all right? Really? Money and everything?”

“Oh,” she said, “That’s no problem. I have enough of that.”

I got into my car to drive across the field to check on the workshops. Alice yelled, “Bruce, wait!”

I waited. She gave me a small beige card. The front said “Alice Ochs. Photographer.” It had an address and phone number in smaller letters. “That’s what I’m doing now in case you want to tell anyone.” I still have the card.

The next time I saw Phil, he was living in a flat just off the corner of MacDougal and Bleeker in the Village, a few doors from the Rienzi. He was taking a crap when I got there. A young woman who said her name was Lana let me in. She was, she said, Australian. She told me that she never went out in the day. I said that was an interesting affectation. Lana said it wasn’t an affectation at all: her visa had run out three months earlier and if she were picked up by anyone official for anything they’d ship her home immediately and she didn’t want that. She said she was a singer, too, but she couldn’t perform without a visa. She paused for a while, then said, maybe she would go home after all. She could apply for a new visa and then she could get maybe get gigs. She wondered if I thought that was a good plan.

The toilet flushed and Phil joined us. We smoked and went out, leaving Lana behind. I forget the stops along the way, but we wound up in a joint where the waitress brought us a huge tray of bagels, lox, and mounds of cream cheese. She put the platter on the table and just stood there, hovering.

Phil said, “We just ordered beer.”

She said, “I loved your album.”

I would see Phil only twice after that. Both times were at Newport Folk Festival post-concert performer parties. I was one of the directors of the Festival by then. After the evening concerts, we would have, in one of the Newport mansions the Festival rented to house everybody, dinners and parties for all the performers and their families. People played instruments and sang deep into the night. There’d be country in one room, blues in another, Cajun in another…

One night, everyone cleared off an epically long dining room table so Junior Wells could dance from end to end, playing his harmonica, while his pal Buddy Guy wailed away. All the furniture was pushed back against the wall and the room filled with people. We kept urging the two of them not to stop. I can’t imagine what the surface of that long antique polished table was in the morning light.

Another party evening I saw Janis Joplin sitting on the staircase, drinking out of a pint bottle of Southern Comfort. Those Newport performer parties were communal and she was the most alone person I ever saw at any of them. There was no way to say that. What I said instead was, “You look bored.”

“I’m always bored,” she said. I’d seen her on stage only a few hours earlier: no way she could have been bored during that electrifying event. Maybe the rest or the time—day to day life, parties, hanging out—but not on stage.

Janis Joplin, Newport 1968 Photo: Bruce Jackson

George Wein couldn’t stand Janis on stage. He told me, when we were standing in the wings earlier that evening while she was performing, that he didn’t like what she did to blues, but I don’t think that was it at all: it was that George found her obscene. I argued with him a little, but not very much. Janis would have been less sexual on stage only if she had taken her clothes off, because then there would have been nothing left to suggest. What George couldn’t accept, and what I didn’t yet understand, was that it was, in all likelihood, sincere: performance was for her the superfuck of all superfucks. Little wonder the rest of the time was boring.

There was always a logistical problem with those post-concert parties: we wanted all the performers and their families to have easy access and we wanted to keep crashers at bay. Year by year, more and more people found out about the parties. Nobody would go bonkers knowing that an Appalachian fiddler or a blues performer was there, but let word get out that Bob Dylan or Joan Baez or Janis Joplin or Peter Paul and Mary might show up and there was an immediate crowd problem.

The directors set up a rotating-bully schedule. I don’t know how else to describe it. We couldn’t ask assistants to turn away People Who Mattered. So we took turns at the door doing it ourselves. Nobody who wasn’t on the program or the family of someone on the program was to be let in.

I was at the door when Phil turned up with William F. Buckley, Jr. Phil (who was not on the program that year) said, “Bruce, you know Bill?”

I didn’t know Bill. I knew who Bill was. I loathed everything he wrote and everything he said on TV. I hated his Yalie smirky smile. Maybe I said something like, “No, I don’t. Why do you?”

I weakened and let them in. I wound up having an interesting conversation with Buckley, no part of which I remember.

In 1968, Phil did it again. This time, the crasher problem was more acute. Pete Seeger or Oscar Brand had been on the door before me and when it got to be my turn, whichever one of them it was told me it had been awful: he’d had to turn away friends.

I got on the door. People who were on the program turned up: I waved them in. People who weren’t turned up: I waved them away. Then Phil, who wasn’t on the program, turned up. His companion this time was Jerry Rubin. I hadn’t met Rubin, but I knew who he was. I thought about my relationship with Phil and I thought about what Pete or Oscar had just said.

I said, “No. No crashers. Sorry, Phil. It’s performers only. You know that.”

“I’m with Jerry Rubin,” Phil said.

“Yeah,” I said. “It’s only performers, Phil. Look in there: the place is jammed.”

Phil called me a “cop” or something like that and they left. That was about the time when Jerry, Abbie Hoffman, Paul Krassner, Phil and some other people were forming the Yippies, which would play such an important part in the devastating 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago.

In spring 1969, there was a big drug symposium in Buffalo. I wound up on a panel seated between Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman. The symposium went as academic symposiums go. While a psychiatrist far up the table was talking, Jerry said, “I have the feeling I’ve met you.”

“I don’t think so,” I said.

“Are you sure we haven’t met?” Jerry said.

“I’m sure,” I said, lying.

Things didn’t go well for Phil after Chicago. He drank a lot. He developed the same bipolar problem his father had. He hanged himself in his sister’s place in 1976. He was 35.

A few years later, my daughter, Jessica, came home from school one day all abuzz with a singer/songwriter someone had turned her on to. “Phil Ochs. He’s fantastic. You should listen to him.” I went over to the record shelf, got the LP and handed it to her. “How cool! You’ve got one of his records.”

“Turn it over,” I said. She looked at the back, then at me. “Look at who wrote the liner notes,” I said. It took her a moment to get it.

“You knew him? What was he like?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Listen to the songs.”

xxx

Photo (and captions) by George Pickow