What follows are remembrances of Amiri Baraka by Sam Abrams, Ammiel Alcalay, Asha Bandele, Julian Bond, Wesley Brown, Benj DeMott, Tom DeMott, Diane di Prima, Bongani Madondo, Richard Meltzer, Jeremy Pikser, Connor Tomas Reed, Aram Saroyan, Robert Farris Thompson & Richard Torres. While there’s nothing official about this tribute, everyone who contributed hopes it might serve as a comfort and/or calmative to Baraka’s wife Amina and his sons and daughters.

Baraka was a brick for the bunch who started First of the Month and he played a heavy role in the back story of our newspaper. (See the About node on our homepage for more on that.) He contributed to our first First and to every issue of our tabloid. His byline gave First one key to blues people. (Whenever I looked out from the steps of Grant’s Tomb at a Jazzmobile crowd reading the newspaper as they waited on a band, I thanked Baraka in my head.) When First morphed into an online journal and Annual volume, he rode with us.

It was always a high honor to print his work, especially his music writing. But there was one piece I wished he’d never had to write—his anguished paean for his daughter Shani and her partner, Ray Ray Holmes, murdered by (to quote Baraka) “a HIN [Homophobic Ignorant Negro] who killed them because he felt it was wrong for these two women to love each other, to want to be together rather than with him, or with other men, black or white, like him.” I feel obliged to recall that heart-break now since one mixed-up summing-up stuck on Baraka’s supposed homophobia claimed his “tears” for Shani “never found a blank page to blossom, an invisible bouquet on her tombstone.” That’s rank nonsense.

Baraka knew his own mind, but he had a knack for collaboration. He never came on from above, never whipped out his rod of correction. I recall how abashed I was after I’d misspelled the name of an activist/artist he’d eulogized in a First piece. When I apologized for my lousy typing/proofing, Baraka let it go lightly while staying true to his late friend: “He ain’t gonna complain (though he would’ve).”

Baraka wasn’t censorious toward First. Unlike many lefts he didn’t insist it have a single line. And he never threatened to step off when other First writers took political stances opposed to his. I recall pointing out the question he’d famously asked after 9/11, “Who?”, had been answered pretty definitively by Charles O’Brien in this First riff on Osama’s apologists:

Poverty caused it, though the perpetrators were all solidly bourgeois and the Moslem ultra-right is founded on the largest reserves of unearned wealth in the world. Desperation caused it, even though the perpetrators imagine themselves to be on the cusp of victory. It was American hegemony, though no-one from the Western hemisphere was involved. It was American political domination, though no-one from a NATO or OAS or G-8 country did it. It was a protest against American pre-eminence: political (with no Antillians involved), military (with no Serbs), economic (with no Mexicans), cultural (with no Canadians). It was our checkered past: Wounded Knee (no Native Americans), Dresden (no Germans), Hiroshima (no Japanese), My Lai (no Vietnamese).

Baraka not only took the points tolerantly, he sent a poem that pushed toward a fresh perception of his own post-9/11 relation to… God and Country, while keeping that “checkered past” in his sights. (His “AFTERNOON W/AN AGNOSTIC” ends on a surprising, rising note of faith and, yup, national—if not exactly patriotic—identification: “It means you actually believe in God/And that was him we bumped into. Dig that!”) Baraka even heard me out when I talked up Iraqi democrats’ case against Saddam and insisted anyone concerned with minority rights should identify with that country’s Kurdish population. I worried sometimes Baraka might not hang tight with First, but I shouldn’t have been nervous. This was a man, after all, who loved poet Ed Dorn because Dorn “wd rather make you his enemy than lie” (per Baraka’s 2000 eulogy for his old friend):

“Ed Dorn/a White dude/Straight as/The barrel/Of a pen

Called his self/A Gun Slinger/Tall rock hard/Slim,

Hey, Ed/Gun Slinger,/You know, we’ll get to argue/Again.”

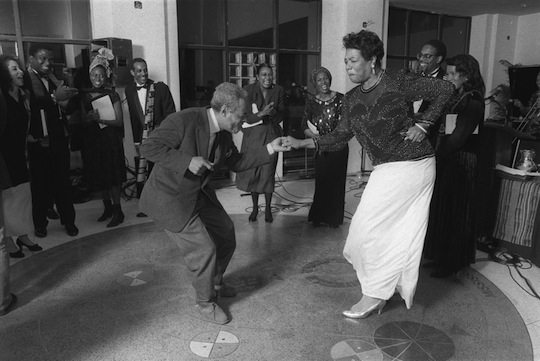

It’s time to bring the band on, but first a couple dance numbers I happened on reading around the web after Baraka’s death. Remember that charming pic of Baraka getting down with Maya Angelou at the Schomburg. (See above.) The Times‘ original, stiff caption for the photo had Baraka and Angelou “highlighting the ancient African rite of ancestral return.” Which moved Ms. A. to ask Mr. B. if he’d been performing such a rite. According to Angelou: “He said: ‘No I was doing the Jitterbug.’ And I said ‘I was doing the Texas Hop.'”

OK, last dance (for now). This one courtesy of Gloria Dulan-Wilson who offered it in her “requiem” for Baraka at Black Left Unity blog spot (Thanks to James Early for steering me there.):

One of the funniest memories I had was dancing with Amiri who had just turned 75. We were at a fund raiser for Felipe Luciano who was running for political office. I remembered thinking that I had to be real careful with Amiri. If something happened and he got hurt or something, Amina would never forgive me. I was looking at him from the standpoint of being 75 years old. And he got out there on that floor and blew me away. He could Latin as well as he did when he was younger!! He moved around that dance floor in a way that put most guys half his age to shame. It was the first time I had seen him dance since the days of the Soul Sessions in New Ark Black in the day. He quipped, “Not bad for an old man, eh?”

Baraka won’t dance—or roar—for us any more. And despair is an option for this not-so-wan White Anglo Agnostic. I hate thinking it’s gone dark before Baraka’s eyes. But, let’s not forget: he always owned the night. B.D.

For Amiri Baraka

don’ matter was it

yr left foot went bad

or yr right

don’ matter yr lungs

or yr heart

don’ matter if that

mass

…..on yr liver was

malignant

or what’s been wrong

so long

…..w/yr kidneys

don’t matter

……………herbs

or western medicine

……………acupuncture

or why you didn’t

go

…..to those appointments

don’t matter how much you drank

or if you drank

don’t matter you did or you didn’t

take drugs

……….meaning meds

or take drugs

……….meaning drugs

what matters when all of us

……….what we wrote

……….what we thought

is lost

…..(& don’t kid yrself, Ginsie

…..it’s all of it

……………gonna be lost)

what matters:

……….every place

……….you read

……….every line

……….you wrote

every dog-eared book

……….or pamphlet

on somebody’s shelf

every skinny hopeful kid

you grinned that grin at

while they said

…..they thought they could write

…..they thought they could fight

they knew for sure

…..they could change the world

every human dream

you heard

……….or inspired

after the book signing

after the reading

……………after one more

……………unspeakable

……………faculty dinner

what matters:

……….the memory

of the poem

……….taking root in

thousands

……….of minds

By Diane di Prima

Spirit in the Night

By Jeremy Pikser

Never a ghost!!! The NYT obit said Amiri had a “small role” in Bulworth. His contribution was incalculable. He not only spoke, but wrote the film’s final words.

Early in the morning of an overnight shoot he improvised, reciting, chanting, dancing in a parking lot—it was so mesmerizing, beautiful and powerful Warren Beatty couldn’t, wouldn’t call cut. Storaro and his men just shot till the film ran out.

Afterward, Beatty looked pale. “I have [paraphrasing here, of course] 20 minutes of the most amazing performance ever filmed and I can’t use more than 30 seconds of it.”

To me Amiri was always generous with his knowledge and wisdom, and kind. So sad there will be no more from him now, so grateful for what he had time to give and how it will continue to sustain us.

A teacher, a leader, a poet, and, of course, not a ghost, but a spirit!

Little Big Man

By Wesley Brown

In the early 1960’s, I was in my late teens when I began reading a jazz column called Apple Cores in Downbeat Magazine, written by LeRoi Jones. Like the name of the column, Jones’ writing cut to the “core,” using a razor sharp intelligence and wit to express opinions on jazz and other related social, cultural and political issues. When I finally saw him read his poetry, I was delighted to discover that, in addition to being feisty, he was short like I was. As someone who identified with Humphrey Bogart in the movie, The Big Sleep when he said, “I tried to be,” in response to a woman who remarked upon meeting him that she thought he’d be taller, Jones couldn’t have come into my life at a better moment.

I read, voraciously, whatever he wrote through all of its many incarnations, and followed his many personal transformations that led to his becoming Amiri Baraka.

I count myself fortunate to have gotten to know Amiri in all of his quarrelsome parts that could be infuriating, incendiary and incandescent. And there is no writer of his generation whose imprint on me as a writer has been more indelible. At his best, Amiri was more than tall enough and gave me the hope that I could be as well.

Core Truths

By Richard Meltzer

Excerpted from the author’s recent review of Beat coffee table books, Beat marginalia (more and less entertaining), and Baraka’s last volume of music writing.

The first writing I encountered by someone I would later recognize as Beat was a series of jazz pieces in Down Beat by LeRoi Jones, as Amiri Baraka was then known. In a mag serving mainly as a tepid trade sheet that routinely shilled for the likes of Stan Getz and Oscar Peterson, Jones’s bold, passionate support for firebreathers like John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor stood in high contrast. With diamond-eyed focus, he championed these musicians NOT as “iconoclastic” contenders, contentious blips on the mainstream jazz radar, but as full-fledged, fully-formed artists whose musical agendas were seminal and necessary. (At 17, I hadn’t read anything that so viscerally spoke to me, and surely it was Jones’s model that enabled me to truck in music-crit myself in the years that followed.)

In the half-century since then, as author of volumes spanning the genres of poetry, fiction, drama, and cultural criticism, Jones/Baraka has established himself as Beat’s only quadruple threat, and today he is probably the most important of the dozen or so Actual Beats still living. Digging: The Afro-American Soul of American Classical Music,” his fourth music book, is a collection of essays, profiles and reviews which have seen the light in the 22 years since the last one (The Music). Virtually everything here is as lively and compelling as his strongest work of the past, and a trio of takes on Albert Ayler (pages 241-260) are together, I would argue, the most incisive, definitive, magical, TRUE portrait of a jazzman and his music—of any era—ever writ. (Believe it.)

Straight out the Motherland

By Bongani Madondo

Just heard of the news of “The Prophet’s” last dance/gig out yesternight having disconnected all kinds media to meditate through the new month of the year. Now, believe it or not, not even Mandela’s last dance ripped me up as Baraka’s departure did. Am still trying to “deal” with it and I don’t think I am doing a good job.

Remember the meeting you arranged for me with Baraka in the Village (Nuyorican Poets’ Cafe) and I got either lost, arrived late, or whatever, that being my first arrival in Gotham, a farm boy from a village in South Africa, ‘member that?

Aha!

And many more interactions with Baraka, back in the 1990s.

Ok,the first thing I did when I heard the news I raked throughout the whole house looking for my copy of Blues People (my second, third or fourth bible for a long time) and I couldn’t even find it.

Still looking for that poem he wrote for Trane. Read it as young man in London in an alternative-mainline HipHop mag, True magazine. Been looking for it ever since…

So Baraka…For me the other side of the James Baldwin spirit-coin…same-difference: my djalis (as Baraka hisself put it: dja’ li, jahzz, jah—God, jazz, God’s music), so who me be foolin’ that I am not dismantled by the news?

“See Everything Fresh” (Amiri’s Legacy)

By Conor Tomas Reed

On January 9, 2014, in the center of a Harlem Studio Museum exhibition on Afrofuturism (“The Shadows Took Shape”), a friend told me that Amiri Baraka had passed on. This seemed like the right place to hear such profound news. Amiri—poet, playwright, essayist, fiction writer, jazz artist, revolutionary, diasporatician, otherworldly agitator—had so consistently nurtured our links to past and future constellations of struggle that to hear of his death made the enduring brilliance of his life flash outwards even more.

A select chronicle: Amiri’s 1958 story “Suppose Sorrow Was a Time Machine” envisioned his own family’s history as an emotional time-loop knotted by racial violence. His 1963 work Blues People re-positioned Africana music in the U.S. as a praxis of cultural evolution and secret resistance. In 1967, Amiri and Amina co-founded the Spirit House in Newark, a home for poets, dramatists, musicians, and other cultural workers to galvanize a city-wide Newark movement. The Spirit House garnered the ire of the Newark police during the 1967 city rebellion, as well as the praise of Martin Luther King, Jr., who visited it just eight days before his April 1968 assassination.

Amiri’s 1970 essay “Technology and Ethos,” published in Amistad 2, raised questions of Black space travel and counter-development logics for generations of Afrofuturists to explore. Always unassimilable, Amiri held respected positions as urban intellectual, college educator, and poet laureate of New Jersey, while also being feared by the FBI, police, and neoliberal cultural gatekeepers. His transformations as a Beat, Pan-Africanist, revolutionary Marxist-Leninist, and Movement Elder crafted a long memory of myriad vantage points to encourage struggle through community arts, while critiquing willful establishment acts of cultural amnesia.

I first saw Amiri speak in 2012 as a eulogist for the funeral of Louis Reyes Rivera, an Afro-Puerto Rican poet and member of the long CUNY movement for Open Admissions and Third World Studies. [Editor’s note: Baraka’s eulogy is in That Floating Bridge, the current volume of First of the Year.] Amiri spoke with jubilant praise about Rivera’s legacy, and welcomed us to celebrate that moment of passage among family, community, and jazz music that vibrated the church walls. It felt more like a birthday than a day of mourning.

In mid-2013, I met Amiri at a CUNY Graduate Center event to honor his friend the poet Ed Dorn. Amiri was stooped, lean, measured, a compact man who seemed his age…until he took the podium. That loud melodic voice had the room hollering from his bawdy jokes, then murmuring at how he and Dorn tried to fuse poetry and historiography in a time of enforced forgetting, and then stone-silent as he described how Dorn’s time-loop kinship to white insurgent John Brown should be woven again by people in that room. And with a final blued note of mischievous gratitude, he stepped down and took his seat.

At last, on January 18 of this year, joining over a thousand people in the Newark Symphony Hall to hold Amiri’s memory aloft, I marveled at how our appraisal of his legacy could so proudly rattle that gilded space with laughter, rage, sizzling poetry, and political purpose. As a spate of ruling-class eulogies have excoriated and obscured Amiri Baraka—some having been written and nailed shut before he even died—we must endeavor to share his work even more widely, nurture the healing process of his extended family, and kindle the reflections of those who directly encountered his fiercely inspiring, radically loving presence. Imamu Amiri Baraka, rest in perpetual power.

Life and Times

By Ammiel Alcalay

In light of various mainstream press obituaries, the author took “the liberty of sending out this introduction to Amiri Baraka that I had the honor to deliver just a few months ago at the Cape Ann Museum.”)

If performance, image, object and sound-making are forms of knowledge, then what we now call art gives a unique view of how things in the world are or are not responded to.

In 1944, the great Martinican poet Aimé Césaire wrote “Poetic knowledge is born in the great silence of scientific knowledge” AND “what presides over the poem is not the most lucid intelligence, the sharpest sensibility or the subtlest feelings, but experience as a whole.”

That same year, Césaire’s student, Frantz Fanon, perhaps aspiring to also become a writer, found himself in Algeria as a French soldier, and was horrified by what he experienced; it would lead him to become one of the 20th century’s most innovative psychiatrists, its most important theorist of race and colonization, and an Algerian revolutionary.

On this side of the Atlantic, in the only hemisphere so thoroughly dispossessed that, up until very recently, not one single state used a native language officially, Bebop had already come into being, a phenomenon that Jack Kerouac called “the language of America’s inevitable Africa” expressing the “enormity of a new world philosophy.”

In 1944 Kerouac met Allen Ginsberg and poet Robert Duncan published “The Homosexual in Society,” announcing a new doctrine of human liberation that would also presage his eventual UN-recognition as one of the century’s greatest poets. In 1944, alerted that Nazis and war criminals were slipping through the OSS and State Department to become key policy makers and scientists, Charles Olson resigned from his post in the Roosevelt Administration’s office of War Information to become, of all things, a poet.

Just months before that, in a trial in Alabama over his status as a conscientious objector, Herman Poole Blount, known as Sonny, and later Sun Ra, did the unthinkable: he told a white judge, in the deep south, that if he was forced to learn how to kill “he would use that skill without prejudice, and kill one of his own captains or generals first. The judge said: ‘I’ve never seen a nigger like you before,’ to which Sonny replied, ‘No, and you never will again,’ a response that immediately landed him in jail.” His psychiatric report echoed those of Lester Young, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, and so many others, in which he was described “as a psychopathic personality,” but also as a “‘well-educated colored intellectual’” who was subject to neurotic depression and sexual perversion.” (John F. Szwed, Space is the Place, pp. 44, 46)

These are the over and undercurrents of the world Amiri Baraka grew up in. Born Everett LeRoi Jones in Newark (the city where his son Ras is now running for Mayor) NJ, in 1934, Baraka’s importance and multiple legacies are truly mammoth.

In a review of a book about Billy the Kid, Charles Olson wrote:

what strikes one about the history of sd states, both as it has been converted into story and as there are those who are always looking for it to reappear as art—what has hit me, is, that it does stay, unrelieved.

This sense of the “unrelieved” and the pressure that brings to bear on what poet Ed Dorn called “this permissive asylum,” is enormous, and we know that the past cannot simply disappear. Given the circumstances of destroyed languages and peoples, slavery, and layered diasporas, we have a human, political, and cultural amalgam on this continent that is as dense and complicated as any the world has ever known.

The explosion of expression following World War II—Bebop, Abstract Expressionism, the New American Poetries, the Black Arts Movement, Free Jazz, Afro-Futurism and a host of other groupings—is a massive response to this complexity, and represents an era of creativity that measures up to any known age of accomplishment we can think of. At the same time—facing the academic, ideological, and political straightjackets of the Cold War—these artists were first and foremost thinkers, and their work constitutes a vast realm of hardly explored concepts about the world we actually live in.

Amiri Baraka is one of a handful of the remaining key representatives of this era, and his personal, artistic, and political life cuts through almost every significant intersection of the age. There are no other living American writers able to traverse the traditional generic trio of poetry, prose, and drama, then move into the realms of essay, criticism, autobiography, and scholarship, while making an authoritative mark in each form. In fact, if we take the great British scholar Gordon Brotherston’s definition “that the prime function of a classical text is to construct political space and anchor historical continuity,” then Amiri Baraka is one of our truly CLASSICAL writers.

His disruptive and political practice refuses conformity, allowing imagination to roam between the placard and the eulogy, between eyewitness reports stating facts and cosmic journeys reinstating the kinship of souls. He has both been “anchoring historical continuity” and redrawing the political boundaries of time and space, first in Newark, New Jersey, then in New Ark, out and gone, an otherworldly place through which he channels radio shows, movies, street banter, memories, diatribe, drama, scholarly study, fable, fiction, science fiction, investigative poetics, calculated public rhetoric, and on-the-spot reporting. He is a fantastic witness both to the astonishing un-reality of the daily real and an example of what can be done to answer it.

He has constantly exposed himself and his ideas to public scrutiny, even attack, opening a window into participation in the amalgamation of selves and ideas that form the creative, political subject. Amiri’s example has served as a constant reminder that such selves, ideas, forms, even communities, are won through struggle and confrontation with oneself and the world. They are not cheaply packaged and exchangeable things to pick up or drop for personal gain or according to dictates of fashion. Finally, though, this clarity of purpose rests in a stance, a position, a place one has to come to in consciousness and over which there can be no negotiation. The visibility of such a stance, bound to a real historical context, is itself a call to action, to activate those parts of one’s own consciousness and meet such a challenge in like terms. In recent years, Amiri has been quite explicit about the need to emphasize and carry on his diverse legacies. He has been extraordinarily generous in working with the Lost & Found Project; this began with a small collection of letters between him and Ed Dorn, finally resulting in the complete correspondence, due out from the University of New Mexico, edited by Claudia Moreno Pisano. Most recently, Amiri has lent his support to Il Gruppo, a gathering of writers initially convened to debunk a recent book claiming that Charles Olson was an exemplar of US imperialism, and that “Projective Verse” was based on a military paradigm. Amiri actually published “Projective Verse,” so if Olson is a big imperialist, perhaps, by association, Amiri is a small one. Without further ado, let’s give it up for Amiri Baraka.

[APPLAUSE, which should continue…]

Black Atlantic Depth

By Robert Farris Thompson

The passing of a great mind is, in many ways, incomprehensible.

But I loved the guy and taught his daughters, Lisa and Kellie. It’s imperative that I say something and say it loud and clear.

I first met Amiri at a conference, on Jazz And Black Nationalism, back in the sixties. Amiri was excoriating certain scholars who felt that Brahms, Beethoven, and Bach were “canonical” i.e. above and beyond Coltrane, Miles, Ellington, and other exponents of Great Black Music. I turned to Amiri and said “the three B’s aren’t my heroes.” Amiri whispered back “I’m not talking about you, man, I’m talking about certain greys in general.” So began our friendship.

I couldn’t believe my luck when John Blassingame, the black historian, included me in a Yale bi-racial lecture series on African-American culture. It took place in the early seventies. The class featured Amiri (on black drama), Larry Neal (on black poetry), Bill Ferris (on the blues), and yours truly (on black art history). You can imagine how thrilling it was to have Dutchman and other works explained by their maker. One afternoon I asked Amiri “didn’t I see you at the Palladium in the late fifties?” He answered, “of course, man, mamho was what was happening.”

Now he is gone. May angels guide him into eternity and on to infinity.

Maximum Cool

By Aram Saroyan

I miss the guy even though we didn’t really communicate for decades, but somehow he was like family to me when I first got going, and also, not to forget, maybe the coolest guy I ever knew.

True to the Truth

for leroi jones known as

amiri baraka known as

leroi jones

late sixties

black power raging

fancy west village grocery

barbara on line

at checkout

behind amiri with

two big glowering bodyguards

hi roi she says

bodyguards start for her

amiri stops em says

name was good enough for my mother

hi Barbara

By Sam Abrams

In the Tradition

By Julian Bond (& Amiri Baraka)

What follows are (slightly compacted) excerpts from an interview Julian Bond conducted with Baraka under the aegis of the University of Virginia’s “Explorations in Black Leadership” program.

BOND: Let me take you back to your very early years. Who are the people who developed, nurtured, trained, pushed, slapped, whatever—

BARAKA: Definitely.

BOND:—pulled you along—who are these early influences as a child?

BARAKA: Well, my family obviously.

BOND: Right.

BARAKA: I mean, obviously. My mother and, I guess, grandfather stand out mostly. My mother sent me and my sister all kinds of lessons. I’ve had every kind of lesson that you can imagine. I mean, from piano, you know, drum and art, drawing, all those kind of things, which is very interesting because it meant what? It meant that somebody was determined that you were going to know something. You know, the whole recitation of the Gettysburg Address and all that, the singing of “Ave Maria.” It meant…”You are not going to get away from me, darling, without knowing something.”

And my sister, [was] like that too. My sister took ballet lessons, tap dance lessons. My sister was the only black girl in Newark at the time you’d see ice skating. Nobody else could ice skate. She would be down in the middle of the town ice skating. My mother and I’d be standing there watching her. And my sister ended up as a dancer on Broadway. You know, you can see her in Cleopatra: Elizabeth Taylor’s in the foreground, my sister’s in the back playing one of the African girls. But that is the result of my mother in the main insisting on that. And what’s amazing to me is the question about the arts, that she was emphasizing the arts for us. You know, we were going to be artists one way or another. And, of course, when you finally pulled the gun out of the holster, as you say, when you finally do realize, “Yes, that’s right. I’ve been trained in this”—I mean, this is not just a casual idea of mine.

BOND: But it also means that the Newark community had people who could teach you—your sister—how to tap dance, how to play the trumpet, how to play the drum?

BARAKA: Well my parents were in a circle of young people essentially, young, black folks who were socially focused. You know, they loved to party…I think that’s how I learned to drink beer so much. After their parties, I would sneak out and drain the glasses. They loved to have these parties, but they were invariably either benefits for one cause—black scholarships, you know—they belonged to that little group, the National Association—well, of course, the NAACP, but the National Association of Postal Employees. For instance, my father was deep in that. They knew people like Effa Manley, the woman that owned the Newark Eagles, our baseball team…Then their friends—like my sister’s ballet teacher was my mother’s friend. She taught her ballet and tap. The piano [teachers] were my mother and father’s friends. Although, I had to go out for drum; I had to go out for the art school. But still, they had a circle of friends that were educated and had the same kind of, I guess you’d say, optimistic view of what was possible in the future.

BOND: So, in a way, without intending , aren’t they also preparing you for a public life, to make you self-assured in the public?

BARAKA: Yeah.

BOND: Those recitations and other things?

BARAKA: Well, she—that’s because she had a public life. My mother was one of these young, black women who had been, of course, to college—had not graduated, but went back to graduate after her family, but who herself was used to the Junior Leaguers, the various kinds of organizations…she was used to speaking or making public appearances, of being in charge of organizations. My father was much less out front, but even he was a member of certain of these organizations, including a bowling organization, of which he was the president, called The Nemderolocs. And Nemderoloc of course is colored men spelled backwards. So, I mean, they all had public personas. My grandfather was the founder of one of the largest churches in Newark. So I was used to seeing my own people in public kinds of situations. I thought it was normal…

When I was in elementary school there was the principal who, for some reason, thought that I was a either an informer or somebody that he needed to talk to because he would always say, “And, Everett”—you know, my first name Everett—”And, Everett, what do Negroes think about this?” I’m ten. What do I know what Negroes think about anything? But my parents had taken us to Fisk and Tuskegee we had visited, you see. And apparently that was known and our mother—you know—had come out of college, though she had to get a job doing piecework in those factories. My father had, by that time, become a postman, which, I guess, was the best job for black folks—

BOND: It’s a wonderful, a wonderful job…

BARAKA: Yeah. I mean, so he was in the post office and when the war started, she got upgraded. You know how everybody had a little upgrade? Well, so she then got a job as an office worker for the ODB, the Office of Dependency Benefits, sending out those checks. So even though she had been a college person, she had to do work in those dress factories prior to the Second World War. Then they moved her up to this office worker and she kept going to school. And she began to do social work. And she was a well-known, well-loved social worker in the various projects, you know, the black projects… So I guess that’s where I got some of that combination of always being in the crowd, and at the same time some kind of the public aspect of it.

BOND: And some kind of caring about others had to come from your mother…

BOND: Not just her own family, not just the immediate, but others.

II

BOND: Now what about your great-grandmother? She’s a great storyteller. How does that come to you? I mean, I’m sure she told you stories.

BARAKA: We used to sit out in in Hartsville, South Carolina, population of about three—and it would be getting late. The sun would be going down, and it’d be my sister, myself and then my two first cousins. One of my cousins is the head of the Charleston, South Carolina, Housing Authority. The other one, Loretta, was the first black woman to have a newspaper column in a major newspaper, The Palo Alto Times. But we would sit out on the porch, all four of us, and our great-grandmother—who died, by the way, at 112 or something. She died in a fire. She didn’t die of natural causes; she was cooking pies and something happened; she couldn’t get out of there. But she’d be telling us all kinds of stories usually from the Arabian Nights. She loved the Arabian Nights. But it was not “Open Sesame!” She would say, “Open See-Sam!” So, for many years, I would say, “Open See-Sam!” But she would tell these stories and, man, they were fascinating. And I’m sure some of those stories were variations on what might have been variations.

My other grandmother—my grandmother in Newark, she would tell you the tales coming out of the South, while the one in the South was telling me stories about, you know, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves and the genie coming out of the lamp. I think I’ve always loved stuff like that, you know, slightly science fiction.

III

BOND: Yeah. When did you start writing? I’m sure in school you had to write things, but when did you start writing for yourself?

BARAKA: Geez, about the seventh grade—I had a newspaper when I was in sixth or seventh grade.

BOND: What was it called?

BARAKA: I don’t even know…It was called—geez, that’s a good question. I only had ten copies of it because I’d write each one out myself. You know, it was like four pages. You’d fold the sheet in half and you’d have to copy everything.

BOND: Uh huh.

BARAKA: And I would pass it out to members of the Secret Seven. We had an organization called the Secret Seven that used to meet up under our house. You know, under the crawl space under the porch. What were we doing there? We’d would eat Kits and—you know, candy—and drink Kool-Aid. That was our secret purpose, to drink Kool-Aid. I guess because your parents didn’t want you to eat all that candy and stuff. So when I got to about the sixth grade and started this newspaper—I think I put out two issues in elementary school. But mostly this newspaper consisted of cartoons that I drew with strange commentary. I remember one of them, every time—there would be a hand poking out and saying “Your money!” Oh, it was called “The Crime Wave.” I don’t know what that was. But people would be jumping off a diving board into the pool and there’d be a hand coming out of there and saying, “Your money!” or they would open the door, there’d be a hand coming out saying, “Money!” And I’d try and figure out what was that about. Why were you so concerned about robbery? I also sent President Roosevelt a letter then telling him how he could win the war quicker. It had a house with guns coming out of it on wheels, which I guess is a tank. But the only problem with that letter is I stuffed into the radio because that’s where I would hear—

BOND: That’s where he came from.

BARAKA: Yeah. So I figured he must be in that radio. So, I would put those letters in there. And what was interesting is I was wondering why my parents didn’t tell me that you can’t get to President Roosevelt in that radio. You gotta mail it. But—

BOND: Especially your Dad—

BARAKA: Yeah…But that writing thing, I don’t know. I was a great storyteller. You know, my mother said I was the biggest liar in the world, because I would make up stuff. Why I would make it up? ‘Cause I could…I mean one time the teacher came to my house and asked my mother, “Why do you keep snakes in your basement?” “Snakes?” Seems that her son being late for school one day—

BOND: Had to tend the snakes?

BARAKA: Right. Said I had to go downstairs in the basement and feed the snakes. So this woman actually believed this fantastic story…He had to go feed the snakes. So she was coming to find out about this health hazard. But it was that—always having to conjure up an extra aspect of reality, you know what I mean? Of trying to foist some magical quality on it that I thought it lacked…

I read the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. But then my grandmother used to bring back—’cause she used to do white people’s hair… in the rich neighborhood—these books and clothes she said the people gave her. I have to believe my grandmother. She was such a sweet lady. I would have on kind of expensive clothes that had come out of these white folk’s house, and she dropped by a complete set of Charles Dickens, a complete set of H. Ryder Haggard. What’s the other guy? Kipling. She had a complete set of Rudyard Kipling…

And so I would be reading these books. You know, I read She and all those kind of things, and David Copperfield…So, that was the kind of reading that I was doing before I got to college, you see. And Langston [Hughes] and people like that you knew—I took Langston Hughes for granted because he was in the black newspapers. And he was the only person I knew that was talking about colored people. And so I liked that…

But then my grandfather was a race man, see. Back in the day he was a black Republican and helped build that huge church—was always supposedly setting the pace for black people. So I never, never thought any other way. You know what I mean? My father used to take me to see the Newark Eagles baseball games every time they were downtown. And then we’d go over to the Grand Hotel, which is–they called it—a black hotel. That’s where the baseball players would hang out afterwards, And so I met people like Monte Irvin and Larry Doby when I was a little boy. And so I had a sense of possibility…

You know, my father could fix anything so I’d think he was real smart. And I knew my mother was real smart cause people talked to her like she was…Plus, she was the most beautiful woman in the world, I thought…So…I knew that anything was possible. And also, I used to see my mother go up against these racists all the time. That was another thing. I mean, I knew that you could do that. I remember one time we were in this store, my mother said, “Give me a pound of those nuts.” And the woman said, “You mean the Nigger Toes?”

And my mother said, “Those are Brazil nuts, lady” and threw the nuts down, grabbed my hand and walked out. So I could hear that and I saw that’s the way you’re supposed to act. You’re supposed to treat them with contempt and defiance, you know. Several times I saw her dealing with people like that around a racial thing. So I figured from early on…you don’t let them get away with anything, you know, whatever the consequences. You take it up. Oh, she took those nuts and threw em down—rolling all over the counter…

BOND: So, you knew if the chance came, you could do the same thing.

BARAKA: That’s right.

BOND: Yeah. It was okay?

BARAKA: That’s right. Because one time my mother and I had a funny conversation. She said to me…this is much later. She said, “I don’t know why you want to do these dangerous things,”—with something we were doing—some demonstration, and I said, “What are you talking about? You put me up to it!”…

BOND: Yeah. She set a standard for you?

BARAKA: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely.

IV

BOND: Okay, so then you go to Rutgers,

BARAKA: And so when I got into college, what that did is opened me up. For the first time I read, for instance, James Joyce. Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which I loved…It gave me a sense of another life…

BOND: Now when you say “another life,” what do you mean, because surely even Haggard has given you a look at another life…?

BARAKA: But that was in my house, see.

BOND: Okay.

BARAKA: You see? That was in my house…Now I was in college now in Newark, Rutgers—and the things that Pound and Eliot and E.E. Cummings talk about were different, seemed different somehow…

BOND: And then Joyce?

BARAKA: And Joyce—those were a little more complicated, remember. It was not just the easy—well, you know, not easy ever, but reading of, say, Charles Dickens…The Pound and Cummings and Eliot had a complexity—some of it useful, some of it not useful—I liked Ulysses. When it came to Finnegans Wake, I thought that was like nuts…

[Y]ou know, there’s one other book. One Hundred Modern Poems by Selden Rodman. Did Rodman die? I don’t know. But anyway, as I transitioned in Rutgers, I read One Hundred Modern Poems, and then I got the whole story—or the beginning of the whole story. I read Apollinaire and Baudelaire and Rilke, the people who were…really out there. You know what I mean? And they couldn’t be no further out than the others. But then I could read Bertolt Brecht in this anthology One Hundred Modern Poems. I began to see, “Man, there is a wild world out here…

V

BARAKA: So Howard University—I got sick of Rutgers because I had gone to Berringer, which is all Italian school, you know, and fought that battle…I went to an Italian junior high school…I had got sick of being in a minority—

BOND: Yeah.

BARAKA: I got to—Rutgers…one time we had an intramural track meet and I won about four events. And I said, “Well, this is not even real.” I mean, I’m moderately fast up on the hill where I live, but—I can’t come down here and just sweep everything—the 100-yard dash, the 220-yard dash, the 440-yard dash, and the 880-dash. I just ran away with it. I said, “This can’t be real…This is some kind of aberration. I gotta get out of here.” And that’s when I went to Howard…

BOND: Yeah, I’m going to focus on Howard and teachers in a minute, but what about the difference between Washington and Newark, the cities surrounding Rutgers and Howard, what—?

BARAKA: Well, it was funny because for we Northern students… And we—and some of the Southern students, would defy it all the time. We’d make fun. We’d go to the People’s Drug Store and order all this stuff. You know, they wouldn’t let black people eat in there… we’d go in and say, “Give me five hamburgers, and six sodas and some french fries, and this and this and this,” and they’d bring it in the bag, and we’d say, “I want to eat it here.” “You know you can’t eat here.” Well, I said, “I don’t want it.” You’d go away and you’d leave it there…

Then there was the thing where you couldn’t even go to the movies downtown unless you were a British subject or a French subject. In other words, if you were an African and can show that you were a British subject, you could get in the movie. But if you’re just plain old black American, they wouldn’t let you in. So we began to do all kinds of wild things—put turbans on our head, go down there and speak weird. And, like as not you wouldn’t get in anyway, because they’d say—they’d want to see your passport. But it was funny. And for us it was always a question of defying it. I mean, we were not fixed on defying it, in that sense, but whenever it came up, that was our line. It needed to be defied. It was stupid. Who were these people? They dumb anyway. You know? And then occasionally we’d have to actually… I mean, we got into a fight with some white marines one time as students. And that was funny to us because there wasn’t enough of them to be threatening. You know what I mean? But they seemed to think that they wanted to box with us. I mean, that kind of stuff. So it was always between some kind of low comedy.

VI

BOND: Now you’re at Howard, you’re surrounded by compatible people, you’re making friends—

BARAKA: Yeah.

BOND: What about teachers?

BARAKA: Oh, I had great teachers.

BOND: Sterling Brown?

BARAKA: Sterling Brown. That was the thing then at Howard that I hadn’t realized ’cause I was trying to get out of the mostly white context because it was working on my mind, you know, that being the minority. But then I’d walk into classes, man, and there was Sterling Brown. I didn’t know Sterling Brown. But then later I would find out this great, black poet was my English teacher. Can you imagine that?

BOND: Yeah.

BARAKA: And I would be sitting up there, and then he would be talking. It’s very interesting. I went there, Toni Morrison went there. All of the black students there who sat up under Brown who actually were telling you some things that you even learn today. I mean, the whole thing about black music being the foundation of your history in America and any kind of continuous example of black history. That where the music goes, that’s where the people go. You know? And the music reflects the people. When he first sat A. B. Spellman and myself down in his house and invited us to his house, he said, “That’s your history, boys.” You know, that was like a wave…a shock because it didn’t mean what it came to mean. Somebody shows you these records…they got Bessie Smith and they got Duke Ellington and they got Fletcher Henderson and they got Ethel Waters and they got Billie Holliday and they say: “That’s your history there.” And you say, “Well, that’s the kind of remark that a professor would make,” you see.

BOND: So you didn’t say, “Okay, yes, you’re right”?

BARAKA: No, no, no. But then he would teach us about the music. See, Sterling then sat us down in the dormitory because what he could dig is that we wanted to know about the music, because remember at that time jazz was banned at Howard University’s campus. I mean, that’s how sick these Negroes were. That they had actually become so alienated from themselves in this quest for the great American dream —in which they would be ghosts—that the music was banned. Like A. B. Spellman—he was one of my best friends in college—he would come to the door of the room (we had a sign on it, 13 Rue Madeleine, that was the Gestapo headquarters)—and he would go, [knock, knock]. He’d start singing… “Ode to Joy,” you know, Beethoven’s Ninth. He was in the opera, The Howard Singers sang European concert music. You understand what I mean?

BOND: Right.

BARAKA: Yeah. So when Sterling perceived that we didn’t think that was cool, you understand, he’d say, “You all think you know something about music?,” you know. “Yeah, we know Charlie Parker”—he said, “You come to my house.” And then he started classes in the dormitory, and we would sit in…at the brand new Clark Hall. And he would talk about the music. See? That was completely out. Of course, that wasn’t sanctioned by the university. Quite the contrary.

BOND: But at the same time, the music he’s talking about I can remember being distant from, that is, I embraced Charlie Parker, but Louis Armstrong, it took me a while to—

BARAKA: To understand that.

BOND:—embrace Louis Armstrong—

BARAKA: I understand that.

BOND:—and Bessie Smith. My parents had Bessie Smith records. And they didn’t appeal to me initially.

BARAKA: Yeah. Right.

BOND: Now what was your reaction?

BARAKA: Because what Sterling was saying was deeper than that. He was telling us about the blues, he was telling us about Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey. But what Sterling was trying to make us understand is the historical continuum that that provided, you understand? And to say that “What you don’t know is where this came from.” See? “You like Byrd and them.” But it took me a while to know who Duke Ellington was, and to really know who Louis Armstrong was, you know. I mean, I was an adult before I could dig Louis. And before I really, before I really manifested who that was—the greatest trumpet player, ever, anywhere, you know—I was like in my forties or something like that. You know.

BOND: Yes. I was turned off by what I took to be the clownish—

BARAKA: Yeah, the clownish—

BOND:—aspects of his—

BARAKA: Absolutely.

BOND:—persona.

BARAKA: Oh, yeah. Absolutely.

BOND: And I couldn’t. I couldn’t do it.

BARAKA: Of course…all of those teeth and what not, you see. But then later on, it—and then remember when Louis came out with the thing during the Arkansas—

BOND: Little Rock crisis. Yeah.

BARAKA: Yeah, the Little Rock crisis…I’ll tell you what really blew my mind about Louis Armstrong. He was on—this was much later—he was on a television interview with his manager, Joe Glaser. And the commentator asked him, “Well, Mr. Armstrong, can you tell us in your sixty years of being in the music business what have you learned? …What would you tell young people.” He said, “Well, I’ll tell ya’ one thing I learned is if you’re black and you’re in the music business, you gotta find yourself some white man and make yourself that white man’s nigger. Ain’t that right, Joe?”

BOND: Really? Oh, my Lord. What a remarkable thing.

BARAKA: No, I saw that actually. It made you want to look away from the television.

BOND: Yes. Yes.

BARAKA: I said because he’s obviously been waiting fifty years—

BOND: To say to them. What did Glaser say?

BARAKA: Joe Glaser didn’t say nothing…he looked like somebody had peed on his shoe, actually…He looked just like “Cut to the commercial.” You know?

VII

BOND: Let me tell you a story I heard about you. This is out of context here. You know Werner Sollors?

BARAKA: Of course.

BOND: Werner Sollors was going to be a James Joyce scholar…And he came to the United States [from Germany] and got one of these trip tickets that allowed him to go many miles on the bus. And he lands in Watts as the riot breaks out. He’s befriended by a black woman who lives in Watts and she rescues him from the bus station, takes him to her home. They can’t leave. He’s there with her parents…They turn on the TV and they’re having a panel discussion about the Watts riot. There’s several people on the panel. And this guy says, “Oh, this is terrible. This is awful. This is terrible destruction. Burning, looting, terrible.” Another guy says, “Oh, this is awful.” And they come to you and you say, “This is the greatest thing I’ve ever seen.” And the announcer says, “Well, we’ll pause a moment for a commercial,” and they go away. And when they come back, you’re gone.

BARAKA: You’re gone.

BOND: And Sollors told me that from that moment on he dropped James Joyce, and he decided to study you. I don’t know why I thought of that just now—

BARAKA: Well, because—my reaction was coming from way back, from a whole other thing. It didn’t have anything to do with America the Grand, so much as America the Oppressor… I’ll tell you another story related to that. When Dutchman was produced, on the opening night—I went to the corner after. There were a lot of newspapers in New York then…and I got all these papers. This is in the Village. I got about five or six papers. And each newspaper would say, you know, in variations about “This man is crazy.” “This man hates white people.” “This man uses bad language.” “This man—” And my take on all that was finally, well, they want to make me famous, I see. That’s what it is. No matter how much they hated the work…But, you know, some didn’t. But then, in some kind of not really miraculous, but surprising, fashion to me, there came down at my head this fierce understanding of responsibility. I never had that before. I was like a wild, young Bohemian. You know, I would do whatever was happening. But then suddenly this feeling, “Oh, now you’re gonna make me famous? I see. Now, you’re going to pay for that.” Then I’m going to say everything I ever thought, everything I ever heard, everything my Momma, my grandmother, my father, my grandfather, all those people in the ghetto. Now is my turn to run it. See? And I felt that very clear. I mean, that was not a vague thing. That came into my head clear as a bell. You understand? “Now I’m going to get you.” And so that feeling there, that story, I can see that because I really, genuinely felt that. You know?

I felt like if you’re going to kick our behind all these years…Should we send you another letter saying that we don’t like it?—that whatever had happened, the people did it because they were forced by the conditions and the context. And so be it, and right on. That’s what I was thinking…Now, obviously, you try to provide, as you get older and can see some more productive direction, you know, because, finally, if you’re burning down your own joint that’s got some kind of negative—

BOND: Right. Right.

BARAKA:—feedback.

BOND: Yes.

BARAKA: When Dr. King got murdered, I was out there in the street telling people, “Don’t burn down your own joint, you know, because we did that before.” You know, in ’67…I was out there in the middle of the street now telling people, “Don’t burn down this part of town. This is where you live.” You know? And they started to go downtown…And I knew it was going to happen then. I was telling them then, “When you go down there, you know that them folks are waiting for us with their guns.” Now you know that.

BOND: Yes. They’ll protect that—

BARAKA: Yeah. So we went downtown, but we didn’t—you know, we went down there to put a presence. But by that time I had come to the understanding that, “No, I do not want them to try to run amok down here, because they will get killed.” And I had a responsibility now for that. And so I’m going to tell you, “Do not do that. Stop. We can demonstrate, but do not run amok down here cause they will kill you.”

More of the interview is available here: http://www.virginia.edu/publichistory/bl/index.php?fulltranscript&uid=1

Thank You Notes

By Benj DeMott

“Chris Christie isn’t an asshole, he’s the whole thing.” Baraka threw that line over his shoulder on his way out the door the last time I saw him. We’d just heard Charles Tolliver’s quintet burn through a set at a space in Chelsea where the band was “in residency” last fall. We emailed about seeing that band again and about Mr. B.’s last First posts—a “pol shot” at Newark’s sketchiest and a reprint of his poem “Mandela’s Eyes”—but he allowed early in December: “My health suddenly no bueno.” I didn’t realize how bad it was, and I feel guilty about not visiting him in the hospital. Though I wouldn’t have wanted to distract those who most needed to hug him close at the end. Maybe it was best to have gone out with him hearing jazz and talking politics…

Not that I shared Baraka’s defiant reliance on Marxist jargon, yet there were always times—see CC above—when his truth-attacks were right on the One. Back in 2007, I felt like cheering when he busted the Smiley-idiocy of those who carped about Obama’s lack of a black agenda: “He’s not running to be president of the N.A.A.C.P.!” And when Obama tanked in the first debate with Romney, I went to Baraka immediately, sensing he’d talk straight to our Pres in First: “Get up Obama, Fight Back, Attack!”

There’s one extended piece of straight-up political reporting and analysis by Baraka that’s surely for the Ages. I recall coming across his reflections on Jesse Jackson, Dukakis and the 1988 Democratic Convention in Atlanta about 20 years ago and thinking his essay beat the hell out of, say, Norman Mailer’s Convention reportage. Baraka was all up in his story, but it amounted to more than me-reflux. His essay immersed readers in what now seems like a key chapter in the pre-history of our time. And thanks to Jesse Jackson’s animadversions and contradictions—the drama don’t stop. (It seems fitting Jesse Jackson spoke at one of the two Newark home-going ceremonies honoring Baraka.)

Baraka preserved Jesse’s great ’88 Convention speech with its immortal litany for the Rainbow’s working class—“Most working people are not on welfare. They work hard every day that they can. They sweep the streets. They work. They catch the early bus. They work. They pick up the garbage. They work. They feed our children in school. They work. They take care of other people’s children and cannot take care of their own…” Baraka admitted Jesse broke him down even as he cast a cold eye on the candidate’s compromises. Here’s a taste of Baraka’s speech crit:

Jesse was blowing hard and pretty, like a rhythm blade cut through most of us. “We didn’t eat turkey on three o’clock on Thanksgiving day, because Momma was off cooking someone else’s turkey. We’d play football to pass the time till momma came home. Around six we would meet her at the bottom of the hill carrying back Du Carcass.”

…In the transcript of the speech that has now been changed to “leftovers.” But he and we who heard know what he said and what he meant. That indeed this merriment was much like a holiday, and yes there were those of us down here who weren’t involved in the real business, we were just the marginalia the bubbles rising off the heady brew. We wanted to eat now, but all we were gonna get was Du Carcass, some leftovers. The white men and quite a few white women had already et…

Anyone who assumes Baraka’s dogmas shredded his talent should check his Convention essay (which is reposted on our homepage).

II

The Times obit claimed “among reviewers there was no consensus about Baraka’s literary merit.” It quoted Stanley Crouch speaking for negos. Baraka’s son Ras resisted that move in his tribute to his dad at the Memorial service. But let me amp up Ras’s defence by noting Crouch himself gave the lie to the Times take on Baraka’s “literary merit” in a 2007 interview. Crouch copped then to how much he’d learned from “studying Whitney Balliett and LeRoi Jones, each of whom invented a style that was celebratory in its very eloquence.” And Crouch went on:

When I was a younger guy, I would read his essays in Black Music over and over, and became intrigued with many of people he talked about. In fact, the essay in [Crouch’s volume] Considering Genius about Thelonious Monk, “At the Five Spot,” is in direct response to the essay “Recent Monk” in Black Music. I was determined to outdo him, since he has HIS foot so firmly on the gas in that one. Wow! I thought the highest performance level (that I had seen) of “writing an essay about Thelonious Monk” had been achieved by LeRoi Jones. He made you feel like you were at the club.

Take that Times person and everyone who assumes there’s no consensus about Baraka’s work. Even Baraka’s greatest hater confirms the man set the standard for jazz appreciators.

Course Baraka went pop too. My favorite passage in Black Music might be this famous one from “The Changing Same.”

If you play James Brown (say “Money Won’t Change You…but time will take you out”) the total environment is changed. Not only the sardonic comment of the lyrics, but the total emotional placement of the rhythm, instrumentation and sound. An energy is released in the bank, a summoning of images that take the bank and everyone in it on a trip. That is, they visit another place. A place where Black People live.

White dis-coverers who took what they found there to the bank enraged Baraka. But he also knew there’s not much point in living in America if you don’t regularly take that trip. I’m reminded just now of how his skeptical look mellowed as I tried to interest a former member of the Last Poets in Philip Levine’s “They Feed They Lion”—the deep poem Levine wrote after walking the streets of Detroit in the wake of the 1967 riots. Doubt Baraka or the Race Man from the Last Poets—who was celebrating the publication of his own chapbook at the Barakas’ (and, I should add, was, like Levine, from Detroit)—expected to hear such a plug in that Newark living room. OTOH, our host did his own contrarian thing. When the Last Poet let on he’d become a Muslim, Baraka’s response was to pour the Courvoisier and ask: “Is God a tease? How come this tastes just right if we aren’t supposed to drink it?”

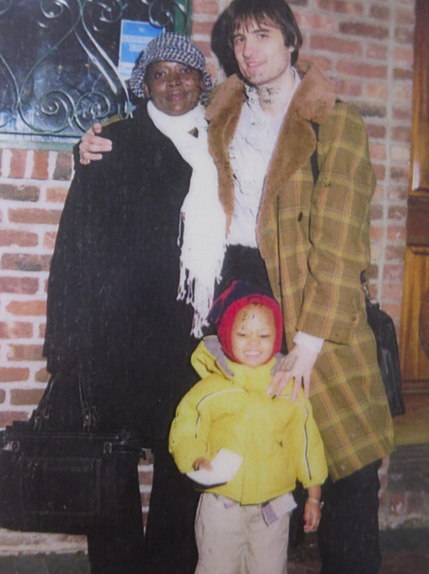

Baraka enjoyed a goof. And he could take a hard joke himself. One of his favorite artists—Senegalese novelist and filmmaker Ousmane Sembene—once nailed Baraka for indulging in a Malcolm X-inspired spate of Muslim piety. In Sembene’s historical drama, Ceddo, the actor playing the Imam who oversees the Muslim imperial assault on African animists is a ringer for Baraka. Yet Baraka didn’t hold a grudge against Sembene. (By the time Baraka saw Ceddo, he was probably cool with its implicit diss of his flirtation with Islam.) Back in 2000, he helped me get through to Sembene, enabling us to print this great African writer’s work in First. There was a sweet personal side to that editorial coup since my wife is from Senegal. A few years later, Baraka gave our family another gift from the Motherland. He let me know Youssou N’Dour—Senegal’s most renowned world-pop musician—would be hanging out at his house after a recording session. N’Dour was a culture hero in my immediate family. It was a great night when my wife and son got to meet (and dance with) him at the Barakas’.

Going to see Baraka (and Youssou)…

Their house was full that night. And my 3 year old had a blast floating in and around the partiers, slipping upstairs, and exploring the stage in the basement. Thinking back on his eve, I’m reminded of Sister Souljah’s Project kid’s angle on her childhood friend Ras Baraka’s social status. Souljah noted at the Newark memorial service she thought Ras was rich because his family had a whole house for itself. When she first said that, I flashed on the big rented digs I grew up in and around as a prof’s son in a New England college town—the Barakas didn’t seem rich to me. But then I thought harder about my little boy, swinging round corners, slipping up and down the stairs as the music played in the background. To a city kid like mine raised in a cramped apartment (even it’s not in a Project), the Barakas’ crib must’ve seemed grand in the best sense of the term.

It’s hard to overestimate what the Barakas’ open house meant to their community in Newark. It was a place of inspiration, an institution that cultivated the audacity of hope outside an American Idolizing culture. Jaunts to and through South 10th St. tended to revive my own sense the margin is the center. I recall how Baraka and his wife Amina made a motley crew of DeMotts and other strangers feel at ease when we stopped by to hear a local bluesman in their basement on our way to a NJ high school auditorium to a Wayne Shorter concert (which Baraka MC’ed). Shorter’s band had an unobvious line-up—there was a black woman drummer—was it Terry Lyn Carrington?—and a Swedish(?) woman on vibes. Everyone sounded great. If memory serves, it’s the only fusion jazz band I ever meant to dig again. A few seasons later, I caught a Shorter set at the Blue Note. He played well (as far as I could tell) but that wonderfully strange band was gone and so was the Ju Ju. It seemed like a money gig—a touristy trip to where black people didn’t live.

III

Baraka’s commitment to his hood brings to mind the Boss’s cultivated Jersey identity. When Baraka was fighting to stay on as the state’s poet laureate after the 9/11 dust-up, I urged him to place himself as heir to William Carlos Williams and forbear to Springsteen. But it occurred to me later Baraka has a tighter connection to another pop cultural icon: Bob Dylan. Dylan has written in Chronicles about how Baraka’s confessional plays got under his skin. And that’s apparent if you get into his Buick Six: “I need a dumptruck baby to unload my head.” (Or consider their Out-rages. You could even twin Dylan at the Tom Paine dinner identifying with Lee Harvey Oswald after the Kennedy assassination with Baraka refusing to come home to America after 9/11.)

Once Baraka and Dylan broke from their Village scenes in the mid-60s, you could hear their changes in their voices. Everyone knows how Dylan wailed on folkies. And if you listen to the MP3s at the UPenn’s archive of Baraka’s readings [http://writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/Baraka.php], you’ll hear how he came to “play fuckin’ loud” too. His blacker-than-that-now-sound, though, cost him more than Dylan’s younger-than-yesterday’s yowls. A memorable scene in Aram Saroyan’s “autobiographical novel”, The Street, set in the early 60’s hints at a sense of loss (which once pricked Baraka’s dialectical muse: “What is most precious because it is lost. What is lost because it is most precious.”) When Saroyan’s hero meets a mentoring LeRoi Jones at a bookstore before a reading:

Jones did something that really startled me and which I’ve thought about since many times. All day long he’d employed a kind of hip, black inflection when he talked, and [another friendly poet] Jim Brodey had more or less followed suit. I could see though that it would be impossible for me to talk in that style and idiom with any conviction so I didn’t attempt it, and mostly, let Jim, a tireless talker, carry the ball.

Then standing in the bookstore, looking over this and that book. I saw Jones approaching me from the corner of the store, wondering if it was me he was actually approaching. Then he was standing beside me and he put a book forward, opened, which I took and began to read.

“Isn’t that beautiful, man.” he said to me, but in a voice that seemed completely different than the one I knew him from up to then. There was nothing in it but naked feeling.

I read a paragraph or so and then handed it back to him, saying wow, it sure is, and meaning more than I could quite fathom. The book was “The Sorrows of Young Werther” by Goethe.

Baraka would say later to the rich pleasures of artful melancholia, which often came with a gay tinge among bohemians. That renunciation may have added fuel to his black fire. Per one critic’s sharp point about James Baldwin in the 60s, “the fury” that lifts Baraka’s writing to eloquence when “he has before him the cruelty of cultural arbitrariness, stems not alone from his experience as a Negro.” I’m reminded of the felt tale of a down-low inter-racial couple dealing with homophobic bullies in Baraka’s short story collection Tales.

But nobody ever called Young Werther nigger. And it’s important to place that “naked feeling” observed in The Street, with Baraka’s own surety that his movement of mind in the 60s wasn’t away from authentic emotion but a prodigal’s return to primal reality. As he put it in Home:

One truth anyone reading these pieces ought to get is a sense of movement—the struggle, in myself, to understand where and who I am, and move with this understanding of it. And these moves, most times unconscious…seem to me to have been toward the thing I had coming into my world, with no sweat, my blackness…By the time this book appears, I’ll be even blacker.

At the risk of hammering on what was shared by those 60s Mercury men, Baraka and Dylan, permit me to note Dylan’s epochal rock move was also a roots one. Village explainers who trashed him as a trend-monger were unaware he’d been a stone rock and roller in his pre-folkie teens (who wrote in his High School Yearbook that his ambition was to “join Little Richard”).

I once talked with a columnist at Inside Higher Ed about Baraka’s and Dylan’s trips and he joked there was a dissertation topic there for someone. Contra Michael Eric Dyson, who urged the crowd at Baraka’s memorial service “not to sleep on that Ph.D”—I’m not playing academic games when I zero in on the kinship between Baraka and Dylan. After all, they had a famous friend (Allen Ginsberg) in common as well as a less-than-lucky one, “banned” journalist Al Aronowitz, (whom I met at South 10th St.).[1] But let’s stay on top not of biographical details but of a structure of feeling.

That Afro-futurist Jimi Hendrix, who traveled the spaceways like one of Baraka’s main men Sun Ra, may be an even more crucial missing link to Baraka and Dylan, though his relation to them is more meta than Ginsberg’s or Aronowitz’s. I’ve been listening lately to Hendrix’s great live version of “Like a Rolling Stone” (from 1968, not ‘66—a bonus track on the re-released 4CD set The Jimi Hendrix Experience—and the playing is worthy of Baraka’s knack for in-the-moment musicing, so let me try to hear it his way.

Hendrix is alive to resonances of the song’s chorus which he sings feelingly, repeating “like an unknown” like a black artist newly conscious—it’s 1968!—he’s a sort of invisible man to his largely white audience. But he’s not beat down. He answers the sung query “how does it feel” with the riff from the Beatles’ “I Feel Fine.” Near the end, he revs the song up and, suddenly, he’s off-road—up into the atmosphere. His playing steers toward guitar future: Allmanesque blue skies, Knopflereseque left turns, and the drop edge of funk’s yonder. But it’s not all forward motion. In the midst of the trip, he breaks Dylan’s “Stone” down to bare do woppy notes. A move that reminds me of Dylan’s own recent gorgeous spin on 50s pop, “Soon After Midnight” (on Tempest). Dylan hangs out longer in the past: “A gal named Honey/Took my money/She was… passing by.” He holds on to that “passing” (underscoring it like Hendrix repeating “like an unknown”). And his reading of the lyric brings back an Age of Anxiety when honeygirls and honeyboys were tempted to pass for white. (See Anatole Broyard’s Kafka Was the Rage.)

Without Baraka’s ears, “Soon After Midnight’s” “passing” might’ve passed me right by. But he taught us all to make music history.

IV

I belong to a later age cohort than Baraka. His maximum musical heroes—Miles, Coltrane and Monk—are a little too removed from my most personal hearings to fit into these biographs of our comradeship. (Though God bless my pop for hipping his kids to Thelonious Monk Plays Duke Ellington and “It Never Entered My Mind” way back when.) There was, though, one jazz musician who felt like a secret sharer to both of us.

Don Pullen became my favorite jazzman after I happened to see him at the Vanguard playing piano—with the back of his hands and an elbow as well as his fingers—in the Don Pullen/George Adams quartet. For the next decade or so (Pullen died young in 1995), he soundtracked soul-deep moments in my life. I wrote a piece about that a few years ago. (Pullen fan Jeremy Pikser—who contributed to this forum—dug it recently so I’ll take that as an excuse for linkage [https://www.firstofthemonth.org/archives/2005/12/back_to_life.html] There’s a lot of Baraka in there and some Crouch too since he was wowed by Pullen’s chops:

Pullen is able to get effects that resemble what one would expect of a percussive harp, since he has invented for himself ways of stroking the keyboard for splashes of ideas that nearly fuse the notes together, making his variations into bursts of sound… As you listen to Pullen you become aware of how much he knows about giving each note the color he wants it to have. If he wants a note to ping, it pings; when he wants a floating, song-like quality, the note rises from the string and curves in the air.

But it was Baraka who pushed me past Crouch’s formalism toward the content—historical, sexual, racial, familial—of Pullen’s music. Baraka had been tight with the Don since they were soldiers in the Black Arts movement in the 60s. (I had no clue about that when I had my first Experience of Pullen.) Baraka delivered the eulogy at a beautiful memorial to Pullen’s life at St. Peter’s Church in 1995. He reached for inspiration by invoking “our mother when she is wet and on fire” and left off on a high note of identity politics.

Don was my Brother. He could sing to me like from a very old place and I would feel and hear and understand. And then we would be flying, Black up against the guinea blue. In my memory Don is the future waiting to say hello again. And we know life does not end. Don, if you dig it, is where ever Blue is light, he circles just above our heads, invisible and nuclear, telling quiet stories in the voice of the mother tongue, so we are never alone.

If Baraka had split last summer, I would’ve left this there. But since then I’ve had further proof he ain’t going nowhere.

V

When I told Baraka last fall I wanted live music at a book party for First, he sent me to Charles Tolliver’s gigs. The young pianist in Tolliver’s band, Theo Hill, knocked me out. (When he got to swinging with drummer E.J. Strickland, I flashed back on Pullen’s thing with drummer Danny Richmond.) I told Baraka I was going to ask Hill if he’d play a song or two for us since there was a piano at our party venue. When I got up my nerve to approach Hill after a set, it turned out Baraka had already hooked us up. Hill was down for whatever since Baraka had put in a good word for First.

Hill added his touch of class to our party by playing a Billy Strayhorn medley. When he finished “Lush Life” I mentioned once hearing John Hicks play it, so Hill finished our night with Hicks’ “After the Morning.” That was a fave of Baraka’s and it was a kick telling him later about Hill’s grace notes. Baraka’s response was spot on: “That brother’s already amazing!”

It’s going to be a privilege listening to Hill grow into his talent over the next generation—one I’ll share with my piano-playing 10 year-old who goggled at the power and reverie of what Hill put down at our party. Thanks to Baraka, the future of our joint musicing looks brilliant.

VI

Baraka’s memorial service was marked by a forward ever quality. At times it turned into a rally for Ras’s upcoming mayoral campaign. I’m sure Baraka would’ve approved, without begrudging the time allotted united fronters like Cornel West and Dyson. But—what the hey—it’s a dirty job but someone’s gotta do it so…

While Ras linked his own push to the aspirational Obama campaigns of 2008 and 2012, Cornel West trashed Obama. In a nasty demagogic turn, he talked smack about Biden’s recent trip to Sharon’s funeral in Israel. West’s instinct to hype up raw memories of black-Jewish tension was rewarded with reactionary shouts and murmurs. But the truth Obama is the bete noire of AIPAC and the current powers-that-be in Israel marches on. While Baraka wouldn’t have rolled over at West’s B.S., I bet he’d’ve rolled his eyes. I’m reminded of the sly alias he once hung on the well-heeled Brother West in a poem: “Warmly Cost.”

There was a spot of music that should’ve taken the piss out of West later in the memorial service. I can’t claim it was the tribute’s musical peak—hard to top Craig Harris’s trombone solo on “God Bless the Child”—but there was nothing more surprising and moving than the Newark Fire Department band’s rendition of “Amazing Grace.” The healing harmony of the pipers, with its echoes of all those post-9/11 funerals for fire-fighters and cops, brought a sense of closure to the controversy sparked by “Somebody Blew Up America.”

VII

“Amazing Grace,” though, has another moral resonance. It was written by a captain of a British slave ship who stayed in the business of selling Africans even after he’d been “saved” though he eventually came around to aid Britain’s abolitionists. The song’s very existence, which hints how beauty may bloom amid beastliness, defines the limits of Christian piety. It’s a perfect soundtrack for Baraka’s rejection of religion without action: “We’ll worship Jesus/When Jesus do/Something.”

Baraka identified with the ethos of the Enlightenment (even if he didn’t always live up to its values):

”we worship the life in us, and science, and knowledge, and

_____transformation

of the visible world…

throw

jesus out yr mind. Build the new world out of reality, and new

_____vision

we come to find out what there is of the world

to understand what there is here in the world!

to visualize change, and force it”

Baraka’s commitment to Change didn’t mean he couldn’t believe in God (“Dig that!”). But his insistence the actual, visible world not be confused with virtual ones, distanced him from one of our old comrades, movie critic and avowed Christian Armond White. (Armond once printed all of Baraka’s eulogy for Don Pullen, which ran for thousands of words, in the Afro-American weekly, The City Sun, where it took up half the paper.) Baraka’s clarity about what’s real and what’s…ghostly goes to the root of why he’s stayed radical while Armond has gone hard to the right. Armond has come to identify with conservative critics of modernity. Secular progressivism is anathema to him.

I’ll allow I wouldn’t have locked on their different trajectories here if I hadn’t seen Armond on Fox’s Red Eye show this month right after watching clips of Baraka on an old Democracy Now program. Can’t truss DN’s host Amy Goodman ever but it was lucid fun to see Baraka exchange dubious looks with fellow elders on his panel when Michael Eric Dyson motor-mouthed into what Adolph Reed once dubbed “his best Pigmeat Markham meets Baudrillard act.”

Back in the 90s, I’m sure I projected Baraka and Reed and Armond White would be arguing with each other down the line (in First?!) about contemporary cultural phenomena like 12 Years a Slave or better and worse stuff. But Armond has different aspirations now. Per his tweet: “My dream is to be on Red Eye.” Well it’s come true. Hope he’s happy but it doesn’t seem real Christian of him to be so at ease among the smug. Red Eye is a cheesy realm of Schadenfreude, not an embattled outpost of Compassionate Conservatism. It was surreal to see Armond yucking it up with the show’s snarky little Thumb, Greg Gutfeld, whose idea of humor is a faked home video of a Mexican peasant being knocked over by a farm animal as he’s pissing into a river. There was another brother on the Red Eye panel along with Armond, but he was a black comic there to play himself (announcing he’d be watching the Superbowl in a strip club since they have the best screens etc.). There was a black woman too who wore a slinky red dress and seemed to be auditioning to become the Party of Lincoln’s Robin Givens. She was proud to have dissed Richard Sherman on Twitter and scoffed at the idea “thug” had morphed into the white gentility’s substitute for the n-word. She was one of those killer women on the right who assume there are no victims in America, only losers (who aim to be takers).

Armond seems to have bought into a mean old Coulter-world where envy is the chief currency, though he’s retained a sense of his own victimhood. He was recently expelled from the New York Film Critics Circle after he was deemed to have acted rudely at the Circle’s Awards Dinner. He sees himself as a Master Thinker under attack by puny Godless p.c. hacks and Hollywood boosters. But he may have more to fear from his own cult-like supporters who think love means telling their angry Lieutenant he’s never wrong.

Baraka attracted some dicey fans along the way too and he was never hot for apology tours. Yet when he looked back on his times on the cross, he’d be the first to admit there were occasions when he wasn’t entirely blameless. (Check his Autobiography or “Confessions of an Anti-Semite” or his self-lacerating eulogy for Shani or his son’s loving line at the Memorial: “Every mistake he made got us closer to the truth.”) Baraka could face up to his own errors and guilts because he knew he had plenty of good reasons to dig himself. Though he pretended to disdain Jesus’s Golden Rule, he was one of the great givers of his era. I hope I’ve managed to convey how lucky I feel to have been one of his numberless…legatees.