Another visit by another Greek premier to London, another bout of speculation about the future of the Parthenon marbles, another poll showing that the British people are happy to see them shipped off to Athens, another slew of liberal commentators expressing with characteristic superficiality the view that the marbles “belong” in Greece, another failure by almost everyone to ask what might be lost if that were to happen.

Not that it constitutes much of an argument, but in fact the level of public support for the restitution of the marbles seems to have dropped by over 20% in the last decade, from 77% to 53%. It may be that this has something to do with the issue becoming yet another front in the culture wars, with Reform and its media boosters coupling the metopes in the British Museum with the fate of the Chagos islands. One result is a double irony in which the Right wants to charge people to see the marbles and the Left advocates free entry not to see them.

…

A question of belonging?

The case for return doesn’t change much. In 2022 The Times, whose recent editors have had an uncomplicated relationship with the arts, changed its previous view and made a limp call for the marbles to go back. “The sculptures belong in Athens” said the anonymous leader writer, “they should now return”.

But why do they “belong in Athens”? It’s obvious that the question of belonging can’t solely rely on where something was made or originally used or displayed. For example if you want to study British art then (when it reopens again next year) you’ll need to travel to the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut. The Center holds 2000 paintings, 20,000 drawings and watercolours, 31,000 prints and 200 sculptures, including works by Blake, Turner, Gainsborough, Constable, Reynolds, Thomas Lawrence, Stanley Spencer, Gwen John and Walter Sickert. The website is hereL https://britishart.yale.edu

No one as far as I know has ever argued that this collection belongs in Britain by virtue of being by British artists and (mostly) having been made in these islands. Most Britons simply have no idea it even exists.

Perhaps the “wanting” is partly the point. The sense I got from the Times editorial was simply that the Greeks seemed to care about owning the marbles far more than the British did, so what harm could be done by indulging this desire? As I will argue, the answer is “quite a lot”, but I’ll come to that later, because we have to dispose of some embedded myths first.

…

Symbols and injustices

In the last couple of years there have been at least two separate petitions launched to try and initiate a parliamentary debate on the marbles. Neither achieved a huge number of signatories suggesting that whatever polls show, the salience of the question in the UK remains low. Again, not in itself an argument.

Both petitions contained a justificatory paragraph eliding several different cases for restitution. So petition 1 stated that:

These works are not just pieces of art; they are symbols deeply connected with Greek identity and history. Their return would be an act acknowledging historical injustices while contributing towards cultural restoration.

And petition 2 that:

The Elgin Marbles are intrinsic to Greece’s cultural and historical identity. Their return would rectify a historical wrong and demonstrate the UK’s commitment to ethical stewardship of cultural artifacts.

Two overt justifications are made here and one is implied though completely hidden and it should be acknowledged that all three are applicable not only to the case of the marbles from the Parthenon brought to Britain by Lord Elgin 220 years ago, but to much else held in the museum and gallery collections around the world.

The two contentions are firstly the idea of the particular centrality of the marbles held by the British Museum to Greek “identity” and secondly the claim that a “historical wrong” or a “historical injustice” was committed in the obtaining of them and their subsequent display in London. Neither are intellectually sustainable.

If you engage on this subject with even quite well-informed restituters you will soon encounter a story in which the rapacious (if curious) aristocrat Lord Elgin, ambassador to the Sublime Porte in Istanbul, somehow contrived to get the authority of the Turkish authorities to hack wonderful sculptures from the living walls of the Parthenon and cart them off to Britain. Eventually penury forced his lordship to sell what he had plundered to the British Museum. Meanwhile a bereft but cowed local Greek population was obliged to suffer this vandalism.

This is mostly untrue. Some sculptures were removed from what was left of the building (much of what you now see of the Parthenon was clumsily reconstructed in the early 20th century when there was a fashion for such things) but the majority pf the objects that are to be found in the BM were excavated from around the Acropolis, where some of them had been re-used for subsequent building.

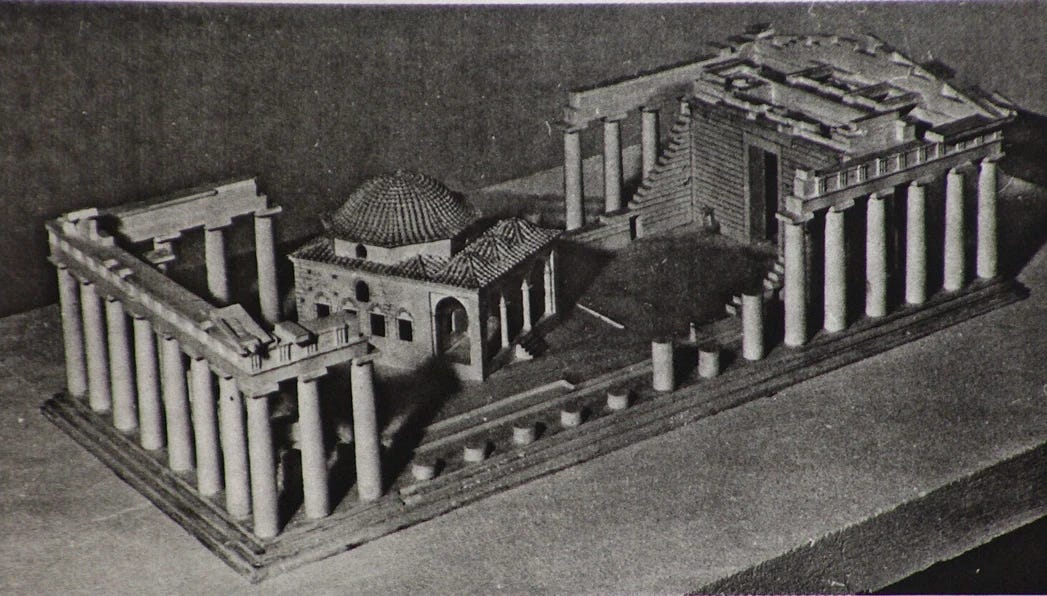

By Elgin’s time the Parthenon had ceased to exist as anything more than a ruin. By the late 17th century the Ottomans, who had taken possession of Athens over 200 years earlier, had established a military base on the Acropolis. When Pope Innocent IX declared yet another crusade in the 1680s, enterprising Venetians made lower Greece their target, which meant occupying the smallish town of Athens.

In September 1687 the Venetians fired an artillery barrage up on to the Acropolis, igniting the Turkish powder store. As the classical historian Dorothy King writes in her book on the Elgin marbles:

The Parthenon’s marble architecture was structurally weak from the Late Antique fire, and the building exploded. Eight columns on the north side and six on the south were completely destroyed, as was the wall behind them, and these pulled the sculpture down onto the ground. Most of the frieze and metopes on the long sides of the Parthenon fell off as a result of the explosion. Although the frieze blocks were larger and stronger and so some survived, the metopes were blown to smithereens. The east end was badly damaged, and the interior of the Parthenon was annihilated… A few blocks survived the full to be buried in the ground, where they would later be excavated by Elgin.

The Venetians abandoned Athens the following year when it was hit by plague and the Ottomans resumed government. After that parts of the Parthenon and its sculptures were taken away as souvenirs, sold by the Turks, used for building by the local population, or – if they were lucky, lay around weathering and ignored. At the time Elgin arrived in Athens there will have seemed little or no prospect of anything other than a continuing attrition of these surviving fragments.

Nor is it true that the sculptures removed by Elgin somehow suffered a worse fate than those that stayed behind. Despite a misguided cleaning attempt in London, an easy comparison exists in the form of the caryatids that survived on the Erectheon and the one removed by Elgin. The ones in Athens were badly damaged by the city’s pollution; the one in London was protected.

This does not constitute an argument against restitution. The new Acropolis museum is by all accounts a splendid institution and there can be few fears about what would happen to the London based Parthenon marbles if they went to Athens. But it’s important to set the record straight.

…

Legality

As it is about the charge laid against Elgin of committing acts of plunder. He didn’t. For all the attempts of propagandists to suggest that he exceeded the latitude given him by the Ottoman authorities, it is plain that a firman – or decree – was issued in Constantinople and supplemented by the local governor. This was done partly to oblige the ambassador of one of Turkey’s most important allies against France and partly because the Ottomans set no great value to these stones. As Dorothy King puts it, “almost no other acquisition of antiquities is as well documented. nor as legal, during any other period in history.”

…

Rewriting history

Which leaves us for the moment with the claim that the Parthenon and anything associated with it is so central to Greek identity that its being located anywhere but Athens represents a historical injustice.

The Parthenon itself was not the product of a Greek nation, but of the city-state of Athens and was probably substantially paid for by taxes levied on other Greek cities who formed part of an Athenian imperium. No Greek nation existed until the early 1820s and the animating spirit of Greek independence was far more about religion than about a sense of c0ntinuity with a classical past. For 2000 years what is now Greece was ruled by the Macedonians, the Romans, the Byzantines, the Latins (Catalans, Normans, Venetians and other exotic riffraff) and then by the Ottomans for over three centuries. At the same time significantly more “Greece” existed outside its current borders than within them. It would as true to say that the fabulous but endangered Altar of Zeus from Pergamon – re-erected in Berlin in the late 19th century – was “intrinsic” to Greece’s historical identity. The only problem being that the site of Pergamon is in Turkey. A Turkish minister suggested the return of the Altar in 2001 but Turks don’t seem to elicit the same sympathy as Greeks. I blame Herodotus.

In fact Christian Greeks in the Roman and Byzantine eras were antagonistic to the paganism depicted in the sculptures on the Parthenon and were responsible for defacing quite a few of them. Obviously they could have no idea of what was going to be claimed in their name a few centuries later.

There is no gentle way of putting this. For centuries – up to and including the period when Elgin was in Constantinople – there was little or no interest among Greeks in preserving the classical past. Just as there had been little interest in England for our artistic and architectural past before what we dubbed the Age of Enlightenment.

Take as an example (timely because of the resumed interest in Thomas Cromwell and the dissolution of the monasteries) of Rievaulx Abbey. Founded in the 12thcentury, hugely wealthy during the 13th, consisting of some of the most beautiful religious architecture in England, Rievaulx was dissolved in 1538, its roofs stripped, its sculptures and treasures dispersed and left a ruin, which itself wasn’t even protected until 1915.

What went around came around. In the same year as Rievaulx was dissolved work began on Henry VIII’s wonderful new palace of Nonsuch in Surrey, built to supercede Francis I’s chateau at Chambord in France. Nonsuch, with its highly decorated stucco exterior, was a wonder of the age and remained a royal palace until the Civil War but reverted to the Crown at the Restoration. In 1671 Charles II gifted it to his mistress Barbara Villiers, Lady Castlemaine, who a decade later, pursued by creditors, pulled the whole thing down and sold it for scrap.

Now imagine for a moment that the Venetian ambassador had come to England at the dissolution of the monasteries and arranged with Thomas Cromwell to cart off large parts of our defunct abbeys such as Rievaulx and their contents and display them in galleries in the Serene Republic. In return Venice would look kindly on England. Or that a Dutch banker had arranged to purchase Nonsuch from naughty Barbara and cart it back to reconstruct it just outside Utrecht. Would we regard ourselves as entitled to demand their return three centuries later?

…

Money for old stones

In the late eighteenth century, for a series of reasons, the curiosity which had become a mark of educated British and French people, flowered into a passion for knowledge about other civilisations and other times. This new passion was not shared by others. So that when these eccentric travelers arrived willing to pay good money or trade favours for seemingly worthless bits of stone, ancient pottery, damaged jewelry or old papers, it would have seemed equally odd to refuse them. To rewrite history as if to transform late 18th century Greeks and Turks and Egyptians into something that they were not is itself something of a colonialist mindset.

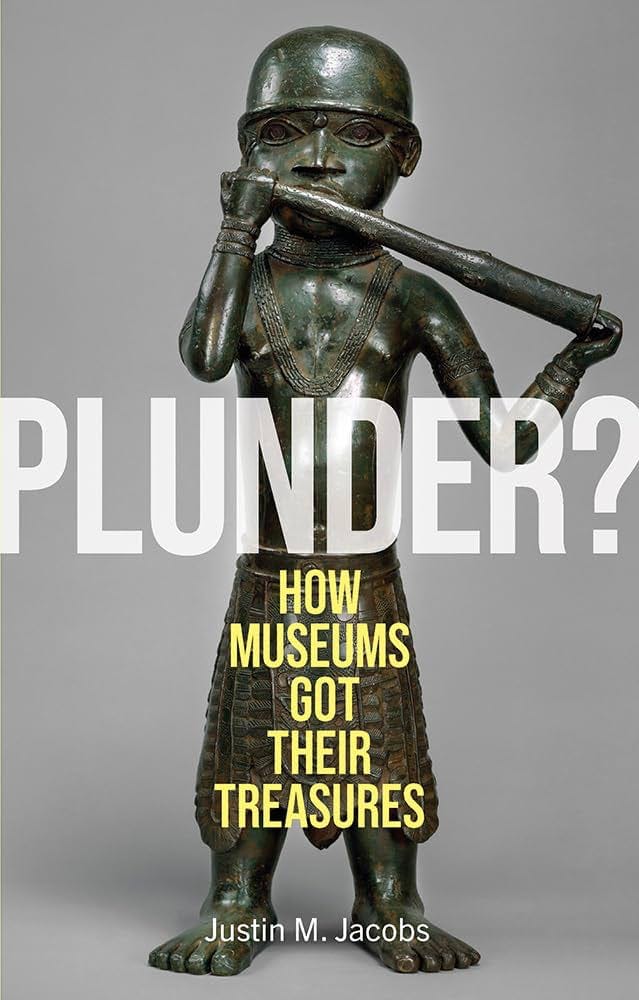

This point is eloquently made in a book published earlier this year. Justin M. Jacobs is a a professor of history at the American University in Washington DC and specialises in Chinese history and art. In Plunder?: How Museums Got Their Treasures Jacobs retrieves the reputation of antiquities scavengers and grave robbers – essentially entrepreneurs who searched for objects to sell – usually to the foreigners that would buy them, there being no local market and little local interest. Later vilified for ruining sites and creating a market for the “priceless” (a term Jacobs rightly questions), these people in fact performed a valuable service, helping stoke the pressure for eventual preservation.

Likewise the scholars and academics who went in search of lost cities and artefacts were almost invariably unaccompanied by soldiers or gendarmes and lived precariously at the whim of the authorities in the places where they were digging. The usual imbalance was not one of power – the white man stealing everyone else’s precious things – but of the value placed upon objects. And that included the notion of what was “intrinsic” to a putative nation. As Jacobs puts it:

It was only western scholars affiliated with an enlightenment institution of learning who said that the objects they collected were priceless emblems of various groups of humanity and should be placed into a museum for preservation and study in perpetuity, without the possibility for the sale.

These days, however, as Jacobs argues, it is not fashionable to express this reality…

The problem is that we now insist on retroactively applying our own set of moral principles – unique to our own era – backwards in time to serve as a historical moral barometer for the actions of long dead historical figures who can no longer speak in their own defence.

Or correct us.

…

The universal museum

I am not arguing that the marbles “belong” in London any more than do the Gwen Johns and Stanley Spencers in Connecticut. They were acquired legally and almost no legal authority short of an Act of Parliament could require or allow the trustees of the British Museum to “give” them to Greece or, I would think to loan them in such a way that it would amount to the same thing. However my case for retaining them doesn’t depend on such technicalities.

The point is that after Elgin brought the marbles to London and subsequently decided he could not maintain them there was an extraordinary museum there to put them in at all. And a unique one at that.

I said at the beginning of this essay that the petitioners for the return of the marbles made three arguments, two overt and one hidden. The hidden implication was that the British Museum is not itself of sufficient value to humanity for us to make the retention of its collection any kind of priority.

I gave up living and dead heroes in my teens making just a couple of exceptions. One of them is Neil MacGregor, the humane, hugely intelligent, liberal-minded and eloquent former director of the British Museum – probably best known to many for his History of the World in 100 Objects. MacGregor’s case for the museum and its collection was its universality.

There would and could be wonderful museums of particular places and times. The new billion-dollar Grand Egyptian Museum near Giza is gradually opening its galleries right now, nearly a decade behind schedule (but who are we in the land of HS2 to mock?) and promising to display 100,000 items, including the Tutankhamun treasures. I can’t wait to visit.

But what MacGregor was arguing for was the coexistence of a place where the cultural achievements of humankind across all continents and all times could be seen set beside each other.

In his 1981 novel Creation Gore Vidal imagined a Persian diplomat of the 6th-5th century BCE who travelled widely and managed to meet Socrates, the Buddha, Lao Tsu, Confucius and Zoroaster. In the same way in the universal museum the visitor and the scholar can move from Periclean Athens, to Persia, to the Magadha empire in India to the Autumn period of Chinese antiquity.

…

As important as the Parthenon

The universal argument is a good one and it certainly refutes the limiting contention that objects should only really be seen in the place in which they originated.

But this is MacGregor’s argument, not mine. Mine is that the British Museum is itself an artefact as important as the Parthenon, that it and its collection is a living treasure born out of a time and place in human history, and one which deserves enhancement not dispersal. And that it is a failure of imagination that prevents so many otherwise intelligent people from valuing the museum as they might.

Essentially the British Museum was formed from an amalgamation of extraordinary collections of art, natural history and antiquities from around the world put together by private citizens in the mid and late eighteenth century. The collections themselves were animated by an almost ferocious spirit of inquiry, which emerged in the Age of Enlightenment.

But what was different about these collectors was their determination that their treasures, books and curiosities be used to spark further exploration and understanding. So the collector, Sir Hans Sloane (he of Sloane Square) when drawing up his final will included a codicil in effect donating his collection to the nation, added these conditions:

And I do hereby declare… that my said museum or collection… maybe, from time to time, visited and seen by all persons desirous of seeing and viewing the same… that the same may be rendered as useful as possible, as well towards satisfying the desire of the curious, as for the improvement, knowledge and information of all persons.

“All persons desirous of seeing and viewing the same” was a unique condition for the age and arguably for any previous age.

On Sloane’s death in 1753 Parliament passed “An Act for the Purchase of the Museum, or Collection of Sir Hans Sloane, and of the Harleian Collection of Manuscripts; and for providing One General Repository for the better Reception and more convenient Use of the said Collections; and of the Cottonian Library, and of the Additions thereto”, one clause of which stipulated that “the said Collection be preserved intire without the least Diminution or Separation, and be kept for the Use and Benefit of the Publick, with free Access to view and peruse the same”.

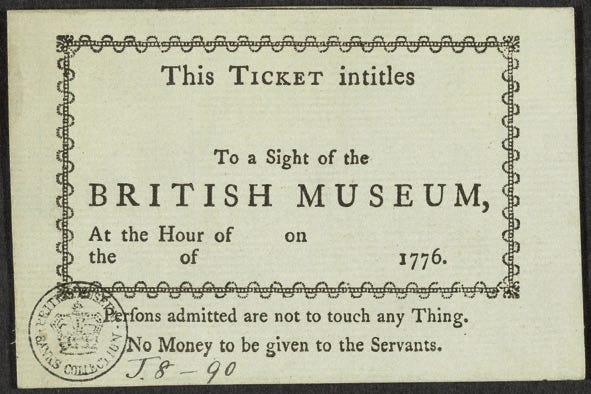

“Free access” had been added to open access. And on that basis The British Museum opened to the public on January the 15th 1759. The building in Bloomsbury came a century later, and the natural history and purely artistic parts of the collection went on to help form the Natural History Museum and the National Gallery.

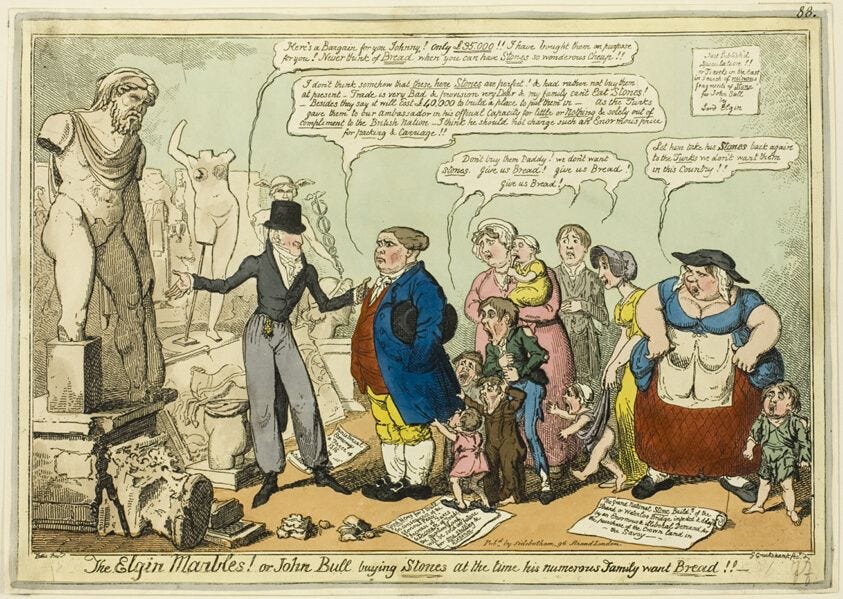

In 1816 parliament passed the act to “vest the Elgin Collection of ancient Marbles and Sculpture in the Trustees of the British Museum for the Use of the Public”, paying around £35,000 for them. This expenditure was not universally welcomed. Byron had already lamented the removal of the marbles to London, preferring that they moulder romantically on the Acropolis. But the main objection was the cost, as represented by the cartoon by George Cruikshank in which John Bull and his family exclaim that Elgin should take “his stones back again to the Turks, we don’t want them in this country!” and “trade is very bad and prices is very dear and my family can’t eat stones!” Applicants to the Arts Council for funds will be familiar with these sentiments.

The determination that anyone who could get along to the museum should be allowed to enter was amplified in an early decision to extend opening times on certain days to allow “the labouring classes” to access the collection. From its opening to today, with a brief interlude in 1974 when entry charges were levied, the British Museum has been free. What happens when charges are levied is expensively demonstrated by what it now costs Britons to visit their own national heritage in Westminster Abbey (£30 for an adult) or the Tower of London (£34.80).

The collection isn’t holy. Most of the objects held by the museum are studied rather than displayed and they are continually being added to and subtracted from. They are lent out and occasionally even nicked; the British Museum is a living, not a fossilised artefact. But it is a breathing monument to the desire to learn, a testament as much to the human curiosity that created it as to the various cultures that contributed to it. It is as magnificent in its way as the Parthenon ever was and to imagine that you can delete the most important and historic parts of its collection without loss represents a cultural carelessness. So by all means vandalise the museum out of an exaggerated and ahistorical generosity, but please don’t imagine that you haven’t lost something precious.

…

Gotcha!

A note on two common gotchas which aren’t relevant to my argument but which will still be raised in the discussion:

1. “We now have the capacity to make exact replicas of objects, including sculptures. So the London marbles could be sent to Athens and replicas put in their place. Bish, bash, bosh, job done”.

Well no. If that is really the case then the obvious thing to do is to make replicas for both Athens and London of what the other holds and extend both collections, meaning that nothing will need to move.

2. “The marbles should be reunified in situ”. Firstly what survives is a fraction of what once adorned the Parthenon so no “completeness” is remotely possible. Second, the marbles wouldn’t be going back to the building they were created for, but to the nearby museum. If that does it for you, then fair enough. Good people can differ.

xxx

Originally posted at Notes from the Underground.