The nausea produced by Trump’s “alternative facts”—which are neither facts nor viable alternatives to facts, being merely lies–has led to a good deal of finger-pointing. Is the seeming legitimacy of such lies owed to advanced (post-modern, “post-truth”) literary theory? For, here, it’s said, readings for the truth of complex texts result in nothing more than a vertigo of indetermination. We have no decisive outcomes but only different hypotheses, having unfathomable degrees of validity, that vie for primacy with no end in sight. It’s not my remit to do a history of the concept of truth-skepticism, but we did not need Foucault and Derrida to introduce us to this great negation. There are paramount exemplars of such concerns in German thought, from at least the 18th century on: Doubts about the accessibility of truth abound, but they are not given equivalent status with lies. The polymath G. E. Lessing acknowledged “the diligent drive for Truth, albeit with the proviso that I would always and forever err in the process.”[1] We have a kind of modern radicalization in Kafka’s skepticism: “A certain [kind of] truth might be found only in the chorus … or choir (im Chor) (emphasis added).[2] Bottom line: we did not need to be vexed by literary theory to declare that “alternative facts” may not be turned into a chorus of part-truth viewpoints and opinions.

As we return finally to another anthropological order, we find the suggestion that criticizing Trump “for not being consistent, reliable, or rational is to misunderstand his leadership philosophy.” Is that true? I’d aver that he has no detectable “philosophy,” unless it’s to have none. By contrast, it’s tempting to invoke, as possibly redeeming, the mind of another ex-President: Barack Hussein Obama. And yet, a first foray into a smart review of his autobiography, A Promised Land, is not so very elating. I refer to an essay in the New York Times by the Nigerian-American novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie,[3] whose argument and rhetoric springs from her disenchantment. Citing Obama’s habit of relentlessly judging himself, often severely, she speaks of a “tendency, darker than self-awareness but not as dark as self-loathing,” adding, “but how much of this is a defensive crouch, a bid to put himself down before others can?”

Now, If by some chance you’ve been reading the new translation of Franz Kafka’s Diaries, the phrase will echo for you in Kafka’s injunction to “dive under and sink more quickly than what is sinking away in front of you.”[4] One might read “sinking more quickly” to mean: Be prepared to imagine, in even greater depth, the insult that is being prepared for you.

Reading further in Adichie’s review, I was taken once more. She writes:

During Obama’s presidency, I would often say, accusingly, to my friend and argument-partner Chinaku, “You’re doing an Obama. Take a damn stand.” Doing an Obama meant that Chinaku saw 73 sides of every issue, and he aired them and detailed them, and it felt to me like subterfuge, a watery considering of so many sides that resulted in no side at all. Often, in this book, Barack Obama does an Obama. He is a man watching himself watch himself, curiously puritanical in his skepticism, turning to see every angle and possibly dissatisfied with all, and genetically incapable of being an ideologue.

Now, following a prepared path, I thought, once more: Yes, Kafka. For one thing, in order to decide whether or not to marry his fiancée Felice Bauer, Kafka drew up a list of the advantages and disadvantages of a settled life for his writing but ended with the gnome: “Whatever you decide, you will regret.” He had not decided anything.

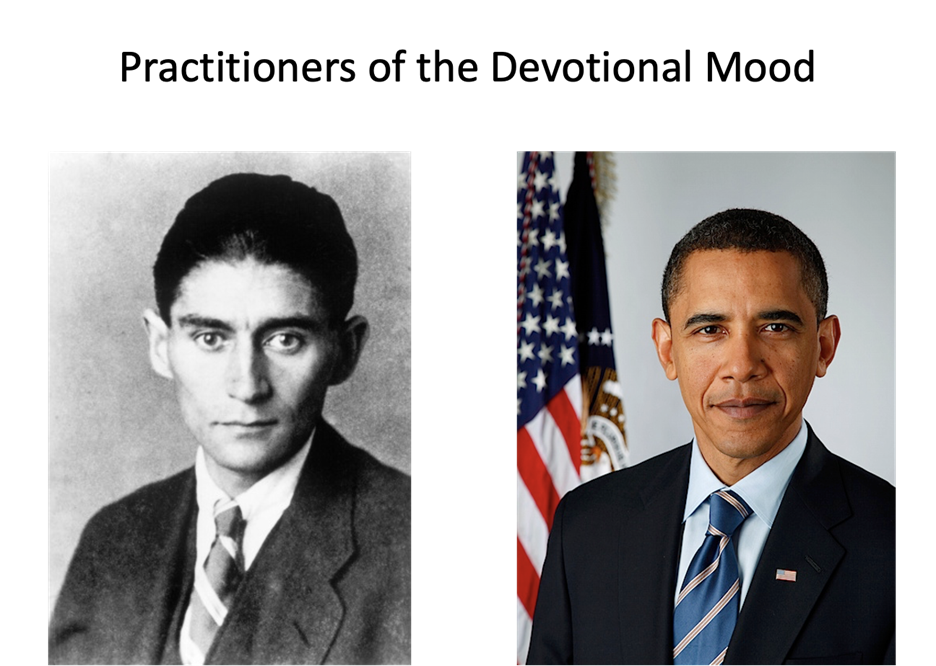

Well, here is a view on Obama and Kafka in similar moral garb, cloaked in indecision. I am beginning to put them together in several ways: Franz Kafka and Barack Obama–an association that has generally gone unnoticed. It may be possible to show that in Obama, a good deal of Kafka lives! — both impossibly lanky, exceedingly articulate minority figures, handsome, with stick-out ears, both, as we shall see:

There’s a lot to consider here, especially in resisting any dispositive conclusion as to the fecklessness of these two extraordinary leaders.

For one thing, it is not true, as Adichie writes, that in Obama “a watery considering of so many sides … resulted in no side at all.” In fact, she records Obama’s pride in one very real, material achievement, “his landmark Affordable Care Act.” And here I was brought to recall an earlier occasion when Obama’s ability to see “the 73 [sic] sides of every argument” concluded—not in no side at all, but in a victorious side. Consider this account of Obama’s style of argument from early days: “He [Obama] won the presidency of the Harvard Law Review in part because, weeks before voting, he made a speech in favor of affirmative action that so eloquently summarized the objections to it that the Review’s conservatives decided he felt their concerns deeply.” [5]

It did not take long to realize what this method was resonating to … It was, of course, Kafka’s very own facility. He possessed this skill in a high degree. It’s well known that the ending of The Metamorphosis was, to his mind, ruined by the “business trip” he had to take while in the throes of composition. Less well known is the fact that the purpose of this business trip was to present a complex legal defense that Kafka won, obtaining a solid judgment for his Workmen’s Accident Insurance Institute. But how, indeed, could he win such cases against highly experienced corporate lawyers? By a similar procedure. We have the evidence.

After he heard the lectures of Rudolph Steiner, the anthroposophist, he described Steiner’s technique, which was to become his own, i.e., the rhetorical rule he calls the “devotional mood”:

Rhetorical effect. Comfortable discussion of the objections of the opponents, the listener is astonished at this strong opposition, further development and praise of these objections, the listener becomes worried, complete immersion in these objections as though there were nothing else, the listener now considers any refutation as completely impossible and is more than satisfied with the cursory description of the possibility of a defense. (D1 54, Ta 159).

There seems to be a compelling ratio here between the weight of the adversary claims that one portrays sympathetically—to which one “devotes” oneself—and thereafter, by contrast, the slightness of touch needed to produce a winning defense. Kafka won. Obama won. His facility in seeing all sides of argument paid off in the Harvard conversation about affirmative action: it led to his presidency of the Harvard Review.

Kafka’s facility also paid off—literally—in a substantial cash payment from the factory bosses he reasoned with, to the Institute he represented. And his ability to see all sides of an argument has another potency, as the generator of his fiction. I’ve written about this potency under the head of “culture insurance,” a concept provided by the Kafka-scholar Benno Wagner, as I shall explain. Kafka’s stories incorporate pieces of his culture with a fullness that is remarkable considering their economy of form. This work of allusion, arising from the movement of Kafka’s curiosity through the cultural vehicles or media of his time, conforms to several logics. One such logic—the logic of risk-taking, involving accidents and indiscretion—would have been inspired by Kafka’s daytime preoccupation with accident insurance.

And so, this thrust: we might view Kafka’s stories as instituting a sort of “culture insurance.” The idea of risk insurance is that the risk of harm befalling one entity (individual, nation, religion, idea) is to be shared by many other like entities (individuals, nations, religions, ideas). If one such entity has the misfortune to suffer harm, others will contribute to compensate the victim for the harm done to it. In this sense, the harm itself (or its mooted financial or moral or cognitive equivalent) is distributed throughout the insurance community; no single entity within the community is injured, diminished, or discredited—partly or fully—without restitution. This logic can be applied strictly to forms of prefabricated thought, to ideologies: they are individually wrong in the sense of being contestable wholly or in part; but, as Kafka wrote, “there might be a certain truth in a chorus [or choir].” The figures in his stories and novels are such choruses or choirs of standpoints, constituting a sort of cultural insurance community. Perhaps, by a bit of a leap, we have concluded our circle, as we recall Obama’s passion, too, for the insurance community that has come to be called Obamacare, brother to this aspect of Kafka’s story world.

NOTES

[1] Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Anti-Goeze (1778), tr. in Christopher Hitchens, God Is Not Great (New York: Twelve [Hachette], 2007), 277.

[2] Franz Kafka, Nachgelassene Schriften und Fragmente II, ed. Jost Schillemeit (Frankfurt a.M.: S. Fischer, 1992), 348.

[3] Barack Hussein Obama, A Promised Land (New York: Crown, 2020). A version of this book review appeared in print on Nov. 29, 2020, on page 1 of the Sunday Book Review with the headline: “Legacy of Hope.”

[4] Franz Kafka, The Diaries, tr. Ross Benjamin (New York: Schocken, 2022), 382. The German original reads: “Es ist notwendig förmlich unterzutauchen und schneller zu sinken als das vor [spatial? temporal?] einem versinkende” (“Zehntes Heft,” Tagebücher 725). Benjamin’s translation reads in full: “It is necessary positively to dive under and sink more quickly than what is sinking away in front of you.” While one blesses Ross Benjamin’s near-complete devotion to the word order of the original manuscripts, the result, as here, is often wooden. Furthermore, the somewhat mitigating adverb “away” after sinking is moot: that which “comes before” you is more likely sinking down deep: the movement is vertical, not horizontal, and hence more sinister.

[5] New York Times, October 26, 2008.