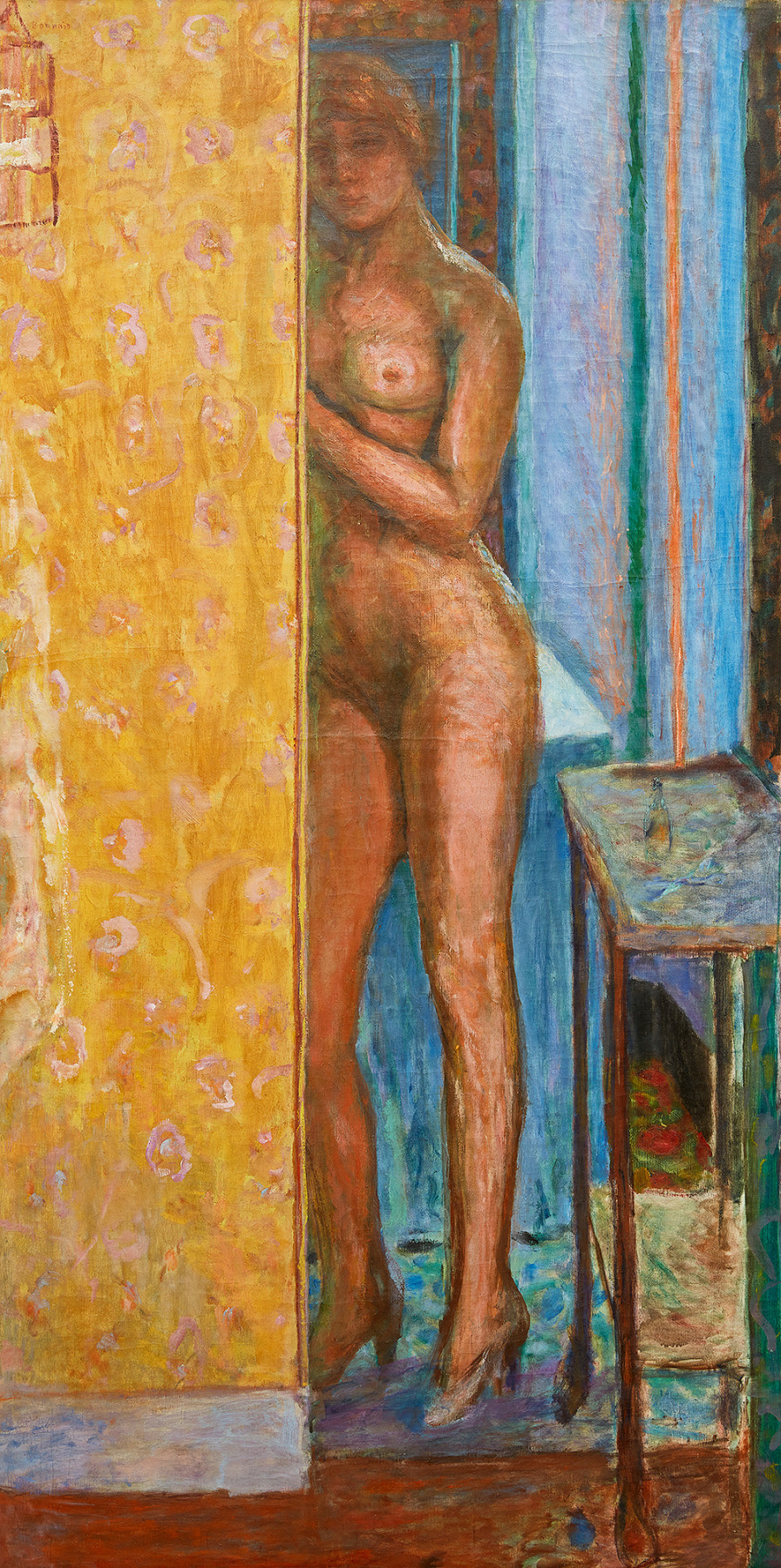

Pierre Bonnard, Nu (Nude, Yellow Screen) 1920

I missed this painting’s tumescent essence when I first saw it in the Bonnard show at the Aquavella gallery. The hard-on architectonics of its straight-up parallel lines didn’t come through to me until I was walking home around the Central Park reservoir. Thin phallic high-rises on the cityscape’s horizon had a Eureka effect. Suddenly I could sense the erection behind Bonnard’s construct.

Lucy Whelan’s newish study Pierre Bonnard, Beyond Vision doesn’t bring up the 1920 Nu, but one chapter, “Escaping with Marthe,” implies it’s a kind of outlier. Bonnard painted his partner (and eventual wife) Marthe, born Maria Boursin, over 4oo times and she’s the subject of hundreds of drawings too. Per Whelan, this body of work, for the most part, resists “the male gaze.” Unlike the “reactionary” tradition of the female nude, posed for the delectation of a male viewer, Bonnard’s depictions of his wife tend not…

to treat Marthe as a passive presence but as an active agent, capable of offering a distinct point of view…Her appearance provides an alternative agency and thus an alternative way of seeing the world that is distinct from Bonnard’s own.

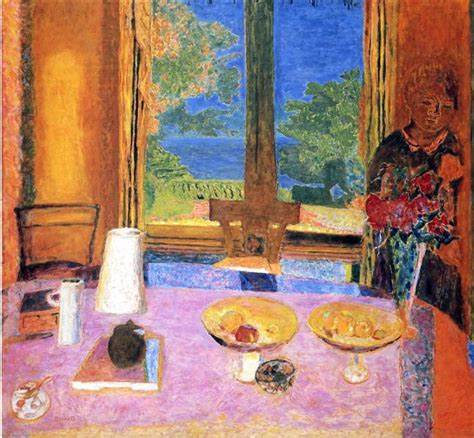

Whelan suggests Marthe is a constant presence in Bonnard’s interiors. (She gives a different meaning to the term wallflower in one domestic view on view at Aquavella where she seems intrinsic to the room — a kind of human retainer ((who is nobody’s slave)).)

Bonnard’s domestic interiors may be more hers than his.

Whelan zeroes in on how Bonnard’s paintings of his wife usually deny the viewer “easy spectatorship of the female body by preventing them from focusing their gaze comfortably on her.” Instead, over and over again, Bonnard tries to evoke what his subject might be focusing on even as she’s a figure of distraction. Dozens of baignoire paintings of Marthe before, during and after her baths are at once deeply intimate and mysterious. What does Marthe want? Bonnard doesn’t pretend to know but Marthe’s way in the world offers him a way out of his own constrictions. (He’s thought-miles away from the dumbstruck critic, quoted by Whelan, who mused on the New Woman in paintings by Manet, Degas and Renoir: “she almost thinks.”) Whelan sees a painting like this next one of Marthe floating and daydreaming in her bath as a testament to Bonnard’s awareness that his wife had a mind of her own.

Pierre Bonnard, Le Bain, 1925

In this bath, unlike many of Bonnard’s interiors, there’s no reference to the artist (or the artist-viewer outside the frame). Instead, the focus is on “Marthe’s absorption in her own private world”:

Without an external relation to the spectator, and willfully looking in her own direction, she creates a point of view within the picture that is hers, that exists independently from that of the viewer looking at her. In this way, we are invited to approach Le Bain with consideration for Marthe’s perspective and to imaginatively attempt to identify with aspects of her experience.

Whelan doesn’t deny the possessiveness that suffuses Bonnard’s baignoire paintings. Monsieur B. is, after all, the One who gets to see Marthe’s ablutions. But Whelan gives more weight to Bonnard’s empathetic impulse. She notes there’s even a baignoire painting, sans Marthe, where Bonnard tried to put himself in her tub.

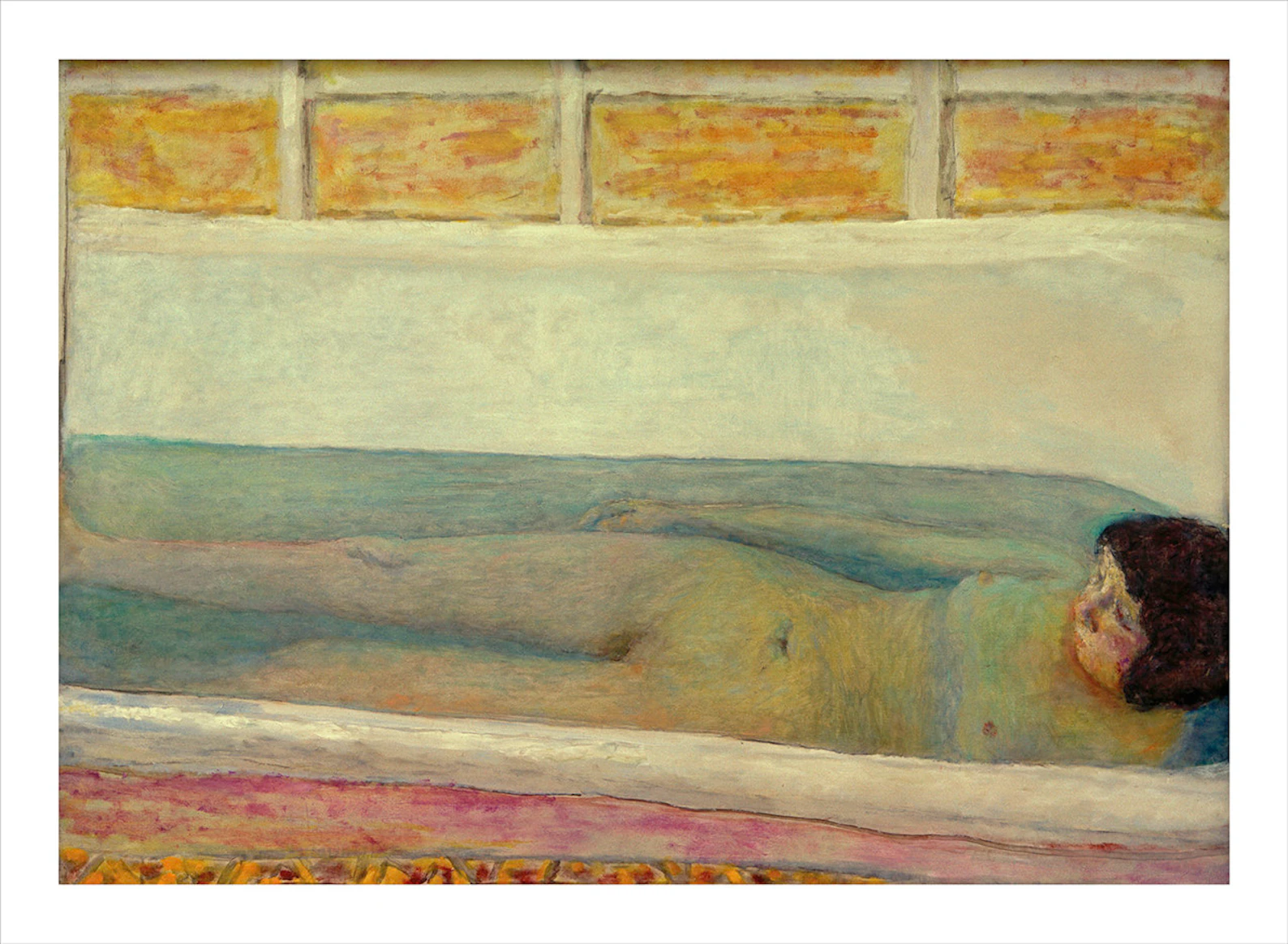

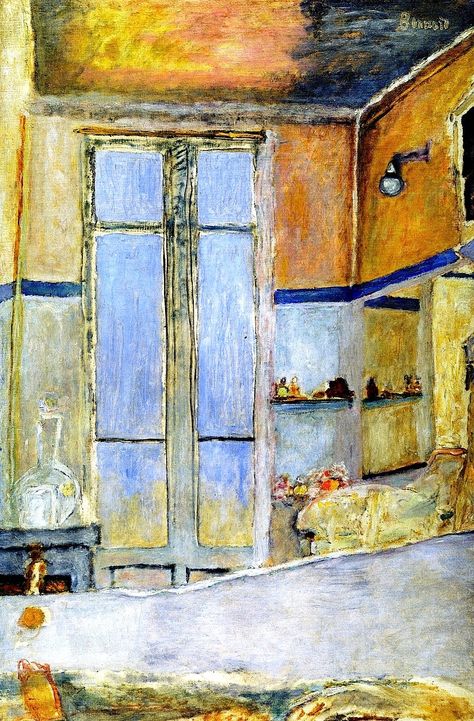

Pierre Bonnard, Dans la salle de bains c. 1940

Per Whelan:

It is as if Bonnard has climbed into the bath to experience the bathroom as Marthe might have seen it. As for the body that seemingly belongs to the point of view offered here, caught as it is in the foreground along the bottom edge of the painting it is signified by a few ambiguous forms in ocher. Most prominent among these is a solid ocher form toward the end of the bath that suggests, not without humor, a penis floating in the water.

Whelan’s eye for Bonnard’s boner is one of many instances in Beyond Vision where she displays her knack for hunting a punctum. Whelan isn’t a show-off but you can tell she’s still thrilled by one of her own moments of vision. She mentions how it took her years before she recognized figures at the heart of this Bonnard landscape.

Pierre Bonnard, Paysage du Midi (Paysage de Normandie)

You may need to go to her book with the detail of this landscape but, trust me, what she describes below is there.

At the center of the Paysage du Midi…is a detail so hidden that it can hardly be seen in reproduction: a figure in a hat, holding the hand of a small child. In fact, I confess that despite having spent countless hours looking at a reproduction of this painting, I only noticed these figures when I visited the painting in the Smith College Museum of Art in Northampton, Massachusetts. Until then I had missed them, despite their location right at the center of the painting, where they seem to walk together along a path that runs under the main clump of trees, the child leading the mother figure along. The painterly surface does not distinguish between figure and foliage, body and space, yet this mother and child are indubitably there, deliberately picked out among the profusion of marks with a few light strokes of pencil laid on after the paint had dried.

Once Whelan gives you fresh eyes, she leads you on to the “impish” black figures further up the path. She connects them to Bonnard’s illustrations for the anti-colonialist japery of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Colonial. That, in turn, allows her to link Bonnard’s mature way of seeing with the anarchist/symbolist/Dreyfusard milieu that shaped his early art-life. Bonnard’s landscapes are wild things — tableaus where he marked time (like Africans, woman and children?), waiting for images to emerge that signified “not just revolt against the white bourgeoisie but the subversion of social and cultural norms.”

Whelan’s notion that Bonnard’s sensibility is anti-bourgeois made me go back to his great paintings of the Terrasse family.

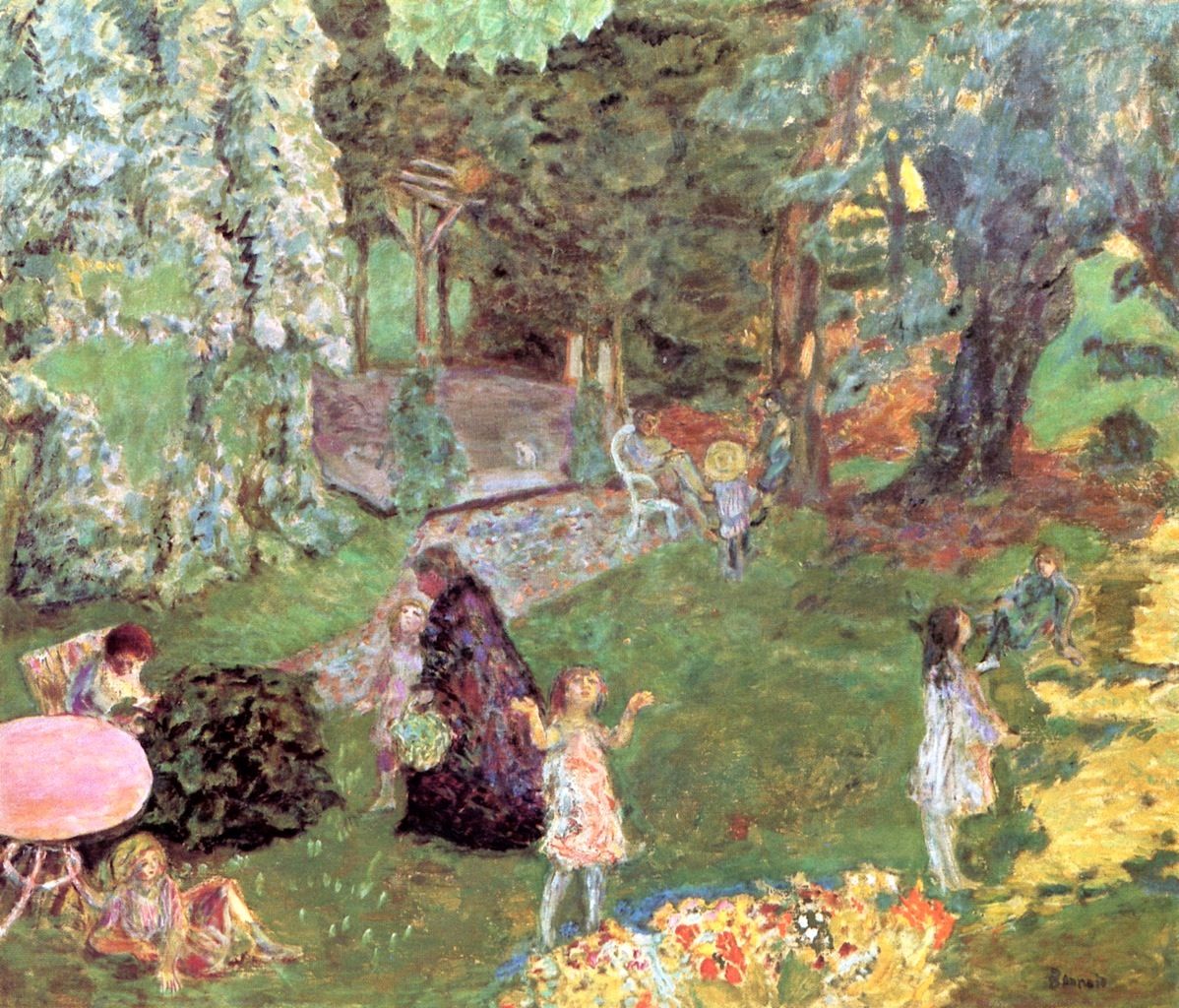

Pierre Bonnard, L’Apres-Midi Bourgeoise ou La Famille Terrasse au Grand-Lemps

The Terrasse Family (Circa 1904)

Bonnard may have been on the margins as he took in his brother-in-law’s family — Bonnard’s sister married the composer Claude Terrasse and they had six children — but his paintings of their bourgeois bonheur are something other than protests, even if irony is in the picture. Bonnard isn’t a proto-Antonioni nailing the bourgeois for their incapacity to sustain a collective fĕte. No doubt the Terrasse family wasn’t a group-in-fusion, yet Bonnard seems to have valued the Terrasses’ capacity to fade in and out of their own familial parade, pairing off or going off on their own. His paintings remind me that when Walter Benjamin said Proust’s best readers would be among the working class after the revolution, Benjamin wasn’t cultivating contempt for Remembrance of Things Past. I’m guessing Bonnard, like Benjamin, sensed there’s no point in trashing a vector of life that might breed selves strong or strange enough to resist the grid.

Bonnard placed himself as a man in the struggle when he imaged himself as a boxer here…

Le Boxeur (autoportrait)

Bonnard’s gaze at his fist brings to mind a line from his notebooks quoted in Beyond Vision: “It is necessary sometimes to draw with the wrist.” A distinction that Whelan links with Bonnard’s preferred tool for drawing—a tiny pencil stub. A choice that underscores how Bonnard’s artistic practice often began not with “agile fingers” out to render what was in front of the artist’s eyes, but with physical resistance (sometimes “with the whole hand and arm”). Whelan has Bonnard engaged in “a kind of rebellion against the standards of the eye, embracing deformations and accidents that occur with the energy behind each scribble and swirl overtakes the interests of the object being depicted.” In her view, Bonnard’s drawings display his fight to get beyond plain sight toward the images that would end up on his canvases. Where he’d keep layering on (then wiping away) paint, brushing off his own “indeterminacy.”

Per Whelan, Bonnard’s choice to cast himself as a boxer “asserts himself as someone ducking bourgeois conventions and niceties, and emphasizes the labor and struggle of painting, both mental and physical.” Whelan notes that in interwar France, boxing was identified with the working class. It was seen as a Jansenist “discipline founded on self-transformation and self-mastery, capable of building virtuous citizens of men from popular or working class backgrounds.”

Bonnard grew up among bourgeoisie professionals—his father even insisted he take a law degree. But his daring equation between his life’s work and the martial art associated with the working class chimes with Camus’s vision in his great speech on Bread and Freedom (posted here now).

I have only ever recognised two aristocracies, that of labour and that of the intelligence, and I know now that it is crazy and criminal to want to subject one to the other, I know that between them they make but one nobility, that their truth and above all their effectiveness lie in union, that separated they will allow themselves to be diminished one by one by the forces of tyranny and barbarism, but that, on the other hand, united they will rule the world.

May this (and every) issue of First be a small contribution to the union envisioned by Bonnard and Camus.