Peter H. Wood and Harlan J. Gradin place the attack on the Capitol in an American historical context…

These days, when angry white supremacists attack their political opponents in public, onlookers use cell phone video to capture threats of violence aimed at elected officials. In May 2020, when armed militia groups in Lansing challenged Michigan’s governor by invaded the state house, images of their brazen action circulated nationally on Facebook and network news. Then in January 2021, thousands of right-wing conspiracy believers, cell phones in hand, attacked on the U.S. Capitol Building and its occupants, hoping to halt official confirmation of a clear-cut presidential election and subvert the orderly democratic transfer of power.

Amidst the mayhem, the self-conscious extremists found time to take thousands of selfies and upload their videos to Parler. Within five days, before that virulent social media site was de-platformed, its vast 56.7-terabyte collection of data, provided by its proud far-right users, was saved by a hacker and a team of archivists. Having scraped this cache of posted images, they geolocated them, reuploaded them, and placed them on an interactive map of the Capitol grounds, giving the nervous public and the global media easy access. Such impressive and often inadvertent crowdsourcing has become a characteristic of our cyber-age.

But in the mid-nineteenth century, conditions for obtaining second-hand glimpses of dramatic public events were strikingly different. There is no Zapruder film of President Lincoln’s assassination in 1865; no hand-held video of John Wilkes Booth leaping from the presidential box at Ford’s Theater; no audio recording of the embittered actor shouting “sic semper tyrannis!” Long before the existence of pocket cameras and phones of any sort, it fell to artists to interpret such events for American citizens, turning written accounts into lithograph images.

Nine years before Lincoln’s murder, no one present in the Chamber of the U. S. Senate on May 22, 1856, possessed the technology to capture the turmoil created by the brutal caning of Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts. No recording exists to confirm the attacker’s claim that Sumner “bellowed like a calf” as blows rained down on his head. Pioneer photographer Mathew Brady had a nearby studio on Pennsylvania Avenue, but he could only create black-and-white daguerreotypes of subjects who sat very still. It would be up to artists to dramatize the event on the senate floor for an image-hungry public.

The attack on Sumner—like the public assassination of Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914—later seemed a key link in a chain of events that led to all-out war. During the late 1850s, as the politically divided United States edged toward open warfare, the Caning in 1856 was followed by the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision in 1857, the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858, and John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859. Following the partisan violence in the senate chamber—just as after the recent chaos on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives—journalists competed for information about the sudden attack.

But how would anxious Americans in the antebellum era gain a visual image of the sensational event? The country’s illustrated press was only just beginning; the first issue of Harper’s Weekly was still more than six months away. For newspaper reporters, the basic facts seemed clear from the outset. In a recent senate speech condemning “The Crime Against Kansas,” Sumner had castigated South Carolina’s U.S. Senator Andrew Pickens Butler for his willingness to force slavery on the West after the Kansas-Nebraska Act overturned the Missouri Compromise and opened the question of accepting slavery to the settlers in these territories.

Days later, Representative Preston Brooks, also from South Carolina and a relative of Butler, entered the chamber in a rage. Brooks, an impulsive politician in his late thirties, had been expelled from South Carolina College. Later, he had been wounded in a duel, so that he walked with a cane. He was joined by Laurence Keitt, another House member from the Palmetto State, who came armed to stave off any interruption of their premeditated attack.

Catching Sumner seated and unaware, Brooks thrashed him with dozens of blows to the head from his heavy cane, until the New England lawmaker lay bloody and unconscious on the senate floor. “Every lick went where I intended,” Brooks later bragged. “I plied him so rapidly that he did not touch me.” Violence among legislators, especially over the divisive slavery issue, was becoming increasingly commonplace by midcentury. Nevertheless, this brazen assault on Sumner inside the Capitol escalated tensions and transfixed the nation. In subsequent generations, other acts of violence would desecrate the building and alarm the country, but until the recent murderous assault by domestic terrorists, incited by a sitting U.S. president, the Caning remained the most notorious act of violence in congressional history.

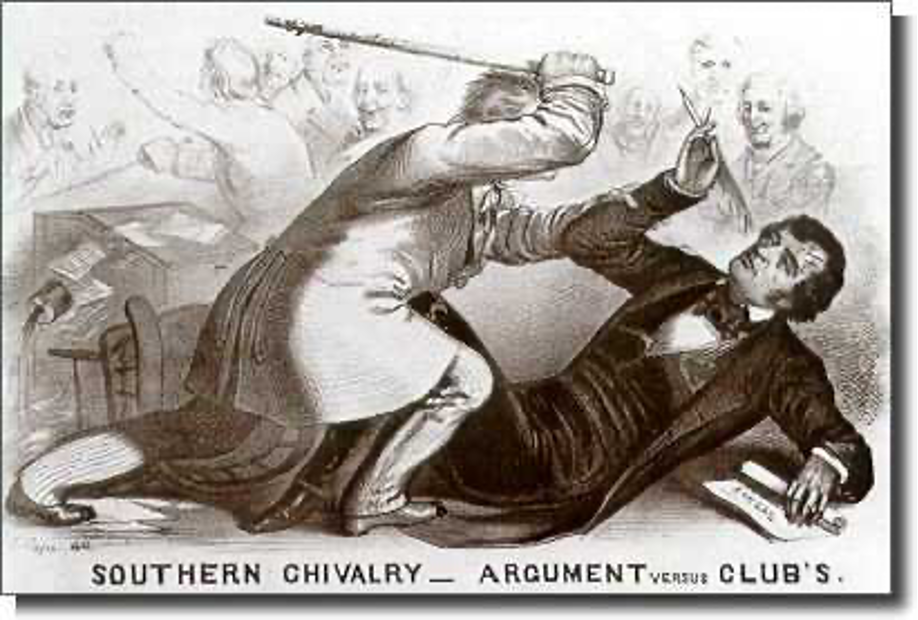

Using the hurried newspaper accounts, several artists quickly filled the visual void by composing lithographs of the event. Most famously, John L. Magee, a New Yorker working in Philadelphia, drew a dramatic portrayal that has provided a startling illustration for textbooks ever since. Magee gave his picture the ironic and poorly-punctuated title, “Southern Chivalry – Argument versus Club’s,” and he featured recognizable details from the press, including Sumner’s overturned desk and the glaring head wounds that would keep him from fulfilling his senatorial duties for several years.

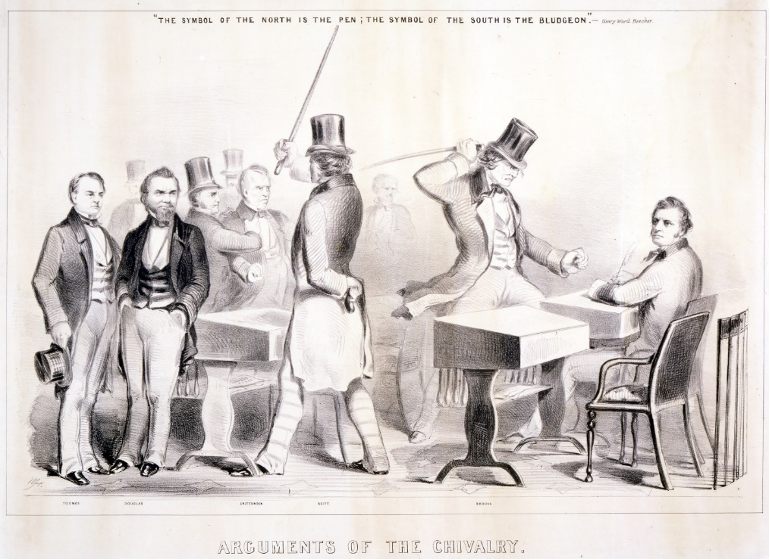

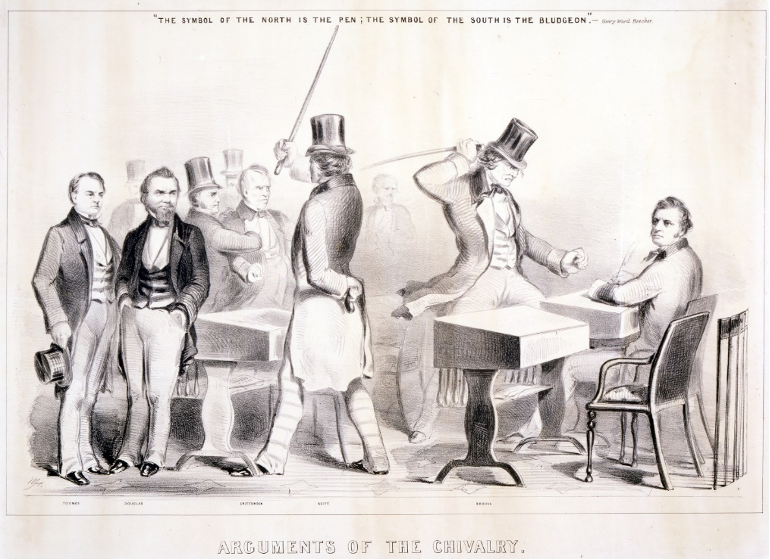

Another illustration is less well-known. Winslow Homer, one of Sumner’s Massachusetts constituents, was an aspiring illustrator completing a dull apprenticeship in a Boston lithography firm. Homer later made a name for himself as a wartime illustrator contributing to Harper’s Weekly, and he went on to become one of the country’s most admired painters. But at age 20, the young New Englander recreated the moment of the assault, calling his picture “Arguments of the Chivalry.” He had reason to feel stirred personally by the violent attack upon his home-state senator, and he may also have felt challenged by catching a glimpse of Magee’s portrayal. Or perhaps he simply received instructions from a supervisor or client interested in responding to the public clamor.

Like Magee, Homer worked the popular term “Chivalry” into his title. (Its contradictory meanings seemed clear enough without inserting “so-called,” in much the way that a modern caption-writer might use the word “Patriot” beneath a picture of Capitol marauders, knowing that most viewers would infer the obvious irony.) Predictably, Homer emphasized the assailants’ canes and high hats, familiar emblems of the southern gentry.

The rendition by the young Boston artist underscored the contrast between building a rational argument—speaking forcefully with a pen to craft a convincing argument—and abandoning reason to win one’s case through a resort to physical violence. Homer even emblazoned across the top of his picture a remark made by the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher a week after the event. The anti-slavery minister, speaking out in defense of Sumner, had proclaimed: “The symbol of the North is the pen; the symbol of the South is the bludgeon.”

Antebellum artists, more than today’s photojournalists, iPhone onlookers, or flag-waving and noose-wielding incendiaries, had the leisure to select the angle and timing of their image. As we have seen, members of the recently sworn-in 117th U.S. Congress, sheltering in place in the chamber balcony and wondering whether rival members were aiding and abetting the attack, lacked the leisure, the incentive, or the skill to compose their numerous hand-held clips. The antebellum illustrators, in contrast, could afford to take their time.

Magee put his audience at floor level and zoomed in on the assault. Homer, in contrast, opted for a wider perspective and chose to depict the instant just before the first blow. Also, in contrast to Magee, Homer gave Keitt’s confrontation with bemused onlookers a more prominent place, taking up half the foreground. On the left and clearly labeled, Senator Robert Toombs of Georgia and his fellow Democrat, Stephen A. Douglas, were prominent supporters of the Kansas-Nebraska Act that undid restrictions on slavery expansion. Sumner’s heartfelt oration had debunked their stance, so Keitt, with his cane raised, hardly needs to restrain them.

Both senators watch with looks of righteousness and indifference; neither lifts a finger to defend their fellow member of Congress from attack. Toombs had definitely been present, and early newspaper reports had Douglas there as well, standing “in a free and easy position, both hands in his pockets… and making no movement toward the assailant.” (His presence was later refuted, which might have been why Homer’s image did not go into broad circulation.)

The beating of Sumner was something Americans could only read about, imagine, and see depicted in editorialized drawings. Both Magee and Homer deployed postures, expressions, words, and symbols to editorialize in favor of the abused Sumner and against the southern ideologues who used violence to defend their worldview of unshakable white supremacy. Generations later, we have hurtled into an era where instant images of political violence abound. Far from being starved for illustrations, we drown in a tsunami of conflicting images, real or photoshopped, and they replicate fast enough to keep our heads spinning.

Now that metal detectors have been installed outside the congressional chambers, one small detail in Homer’s picture takes on sudden immediacy. He sketched the butt of a small pistol concealed in Keitt’s left hand, hidden from others in the chamber. But the provocative firearm is plainly visible to viewers, at the very center of the picture, a reminder that “the time is out of joint” when members of Congress insist on carrying menacing weapons into the Capitol.

One wonders, therefore, how Homer would have elected to depict our own seditious imbroglio, as reports emerge that members of Congress seemed willing to hint to attackers where other members were hiding? He might well have chosen to imagine Republican Senators Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley with their arms folded, taking in the scene of destruction. And he might again have slipped a concealed revolver into the picture too. After all, as one New York representative shaken by the events of January 6 later told her constituents: “I didn’t even feel safe around other members of Congress.”

xxx

Peter H. Wood, the author of Black Majority, is a retired Duke University history professor, now living in Colorado. He co-authored the U.S. history survey text, Created Equal, and in 2010 he published Near Andersonville: Winslow Homer’s Civil War.

Harlan J. Gradin is the Scholar Emeritus of the North Carolina Humanities Council and the author of “Losing Control: The Caning of Charles Sumner and the Breakdown of Antebellum Political Culture” (Ph.D. Diss., University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1991)

Originally posted at Topics of Meta.